Бесплатный фрагмент - Chronicles of the whole world

Heyday time

To my parents

Prologue

— No, mom! Emma slammed the door shut and sat angrily on the bed. The skirt was inflated like a bell, to which the mistress of the skirt began to furiously nail this silk bubble to her legs. In the distance, on the street, there was the sound of a passing horse-drawn carriage, the clatter of hooves, the cries of newspapermen. There, outside the window, people were doing the work for which they were best adapted, and no one interfered with them, did not set prohibitions, and did not threaten to send them in marriage to Berlin. As if a newspaperman couldn’t even sell his stupid papers in Berlin.

Emma pouted her lips in resentment, as if compensating for the restored prettiness of her own skirt, no longer a bell, but quite a girlish piece of clothing. The skirt was new, amethyst, with a deep glossy sheen and dark blue, almost black, embroidered flowers. With a thin, long finger, Emma began to trace the flower. With each new circle, her thoughts calmed down, lined up, took shape and logical sequence. No, in her parents’ house she will remain just a girl, capable of nothing but knixens.

Half an hour ago, when Emma stood in line at the small post office and thoughtfully looked at the back of Mrs. Krause, she knew that this conversation with her mother would take place, that it would end quite expectedly — a scandal, that mother would go out again to smell her salt, and in the evening she would saw her father, so that he would talk to his daughter and guide her on the right path. Emma idolized her father, but she could not cross out her own dream. Then she would cease to be herself and, therefore, would cease to be Emma Sascha Osterman, the daughter of Uwe Stefan Peter Osterman, director of the Storkov Gymnasium. Emma came to the post office with one goal — to cut the ropes.

Most of all, Emma loved the sky. And as if reciprocating the sky was a little closer to her. The thing is, Emma was tall. Above mom, dad and all the misses and mrs of their small town. Her parents were quite average in height, they did not consider themselves outstanding people and tried to correspond to this middle in everything. Emma, on the other hand, has been stretching upward since childhood: climbing trees, jumping from a neighbor’s barn, staring late into the night sky, hovering in the clouds. In a word, Emma Osterman was not like everyone else.

Chapter 1. Not like everyone else

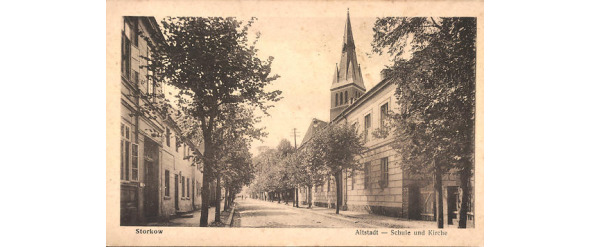

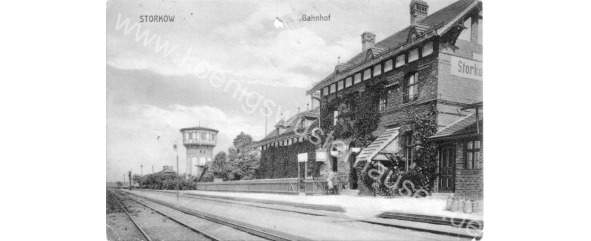

The city of Storkov is located on the lands of the Principality of Brandenburg with all its Prussian pedantry — exactly between the lakes, girdling itself with a canal for beauty. Here, little Emma ran along the coast after a kite, secretly climbed from her parents to the closed Jewish cemetery, played hide and seek with her friends near the old castle, went with her family to the church, resting on the sky with neo-Roman crenellations, like a crown, dangling after school at the old gateway, walked around the market square with her younger brothers: first Jacob, then Klaus, Arnd, Henning, Ivo, and finally the twins Franz and Fritz. Yes, the older Ostermans cannot be called childless. From so many offspring, Lise Osterman dried up early, as if weathered. Many pregnancies did not affect her figure in any way, which is why she still walked without corsets, as thin as a twig, but somehow withered. Early gray hair silvered a dark knot of hair, her shoulders drooped, her gaze faded — in a word, Mrs. Osterman began to get tired of life. Her husband, Uwe, nevertheless loved his wife and was sad because the once cheerful and sonorous girl disappeared, and a little old woman came in her place. Lisa was two years younger than him, but at forty-two she looked much older than her forty-five-year-old husband. For days on end, Mrs. Lise sat in her room or lay on the couch and thought about how fast and bleak her life was. Headaches and fatigue became her faithful companions, the governess Vilda, devoted to the family, completely took care of the children, although she was going to ask for resignation after Arnd, because nothing prevented Lise from covering herself with dust in her boudoir and indulging in useless dreams.

Children, as befits a mother, Lise loved. But love detached, cold and measured. The desire to somehow limit the family circle of relatives, crawling out like yeast dough from the basin here and there, led Mrs. Osterman to a logical and reasoned conclusion in her own way: if you do not show your love to children, then, you see, new offspring will not appear. The nuance that children do not appear at all from maternal love, Mrs. Osterman for some reason missed. Once upon a time, little Emma aroused such delight in Lise that she could not believe in her own happiness. Having children late — where has it been seen that a respectable German woman gives birth to her first child by twenty-five? Mrs. Osterman could not stop admiring the little crumb. Secretly from her husband, she kissed her daughter’s every finger, blew in her stomach and tilted her curls over her, trying to tickle this caramel candy to a low and sweet laugh. Emma pulled her mother’s hair, Lise playfully widened her eyes and kissed, kissed, kissed her impossible happiness. There was no Vilda nearby, and Emma belonged only to her. Her and Uwe.

And then something broke in the universe familiar to Lise, and the children clicked out of it like toy eggs from a clockwork chicken: poke, poke, poke, poke! Lise did not understand how this was possible, but with each subsequent son, Uwe hugged her tighter at night, and kissed her hotter, that there was absolutely no strength to resist this. She didn’t resist. She pecked her grains from the plate, and from the other end — poke, poke, poke, poke. Nineteen years after Emma’s arrival, Lise was so tired that she could no longer see or hear her family. Every creak of the floorboards under Ove’s feet reminded her of a poke, which left Mrs Osterman with no choice but to pretend to be sick or asleep. On the nightstand next to the bed were bottles of smelling salts, vials, and beakers of medicines for anemia, boredom, and old age. Over time, Lise so believed in her invented illness and fatigue that she forgot that she only wanted to get a break. Now her family really oppressed her, her head ached, the bottles were changed and added to the nightstand at some frightening rate, and Lise still refused to change anything.

Mother knew that almost certainly Emma was now sitting on the bed, hugging a book. Lise did not understand this affection and therefore did not accept it. Four years ago, Uwe went to a book fair in Berlin to see the new grammar school textbooks. I brought a book from there. One book. Some book dealer’s daughter fell ill, all the savings were spent on treatment and there was nothing left but to sell the last. The bookish man brought everything valuable and not very valuable to the fair, sold it cheaply, without haggling, shaking his hands and getting excited. Uwe, who adored his daughter, understood the second-hand bookseller very well, but he was limited in money, so he bought only one. The Chronicles of the Whole World was pleasantly old, but not ramshackle. The salary was not rich, skillful. Thin silver curls were arranged in intricate drawings at the corners: a knight on a horse, the sun and wind, a tree and a man under it. On the last corner there was a small magnifying glass and gears. The skin is thin, soft, dark blue, the same as the sky after sunset, when the night has not yet come, but just about. The locks on the book had long been lost, but the binding was still strong and the pages were soft. The folio did not have a mention of the author when it was published — it is not known, engravings included not only military, but also secular topics, it was written in German.

«Two hundred and forty marks?» — Lise was amazed when she found out the price of antiques. — Yes, you’re crazy. We could stock up on coal for the whole winter.

«But coal doesn’t warm the soul, dear. Mr. Weiss did not bargain, the book obviously costs more, — the head of the family peacefully held the defense. «And we were given the opportunity to help in trouble. Don’t worry about the winter, I’ll get the money.

I got it, of course — Uwe never deceived his wife. Ove read the Chronicle in random order and used the book more often to calm his nerves than to gain knowledge. The younger children twisted the book and put it aside, only Emma and Jacob dragged it to their rooms — either to look at the engravings, or to read. More and more often, Uwe began to find his sleeping daughter in an embrace with a book, either in an armchair or right on the bed. The patterns of the salary were imprinted on her tender cheek, Emma mumbled something sleepily and released her jewel from her weakened hands. Gradually, Osterman resigned himself to moving the book into the girl’s room and no longer tried to penetrate the depths of the Chronicle. Jacob and his sister reached a consensus: sometimes he was content with retelling, sometimes he read when Emma was not in the house. He carefully returned the book to his sister on the table. Uwe was amazed at the rare harmony that developed between the older children: they did not share the object of desire, but owned it respectfully and with dignity. A couple of years later, Osterman asked his daughter what attracted her to the Chronicle so much, why she reread it again and again.

«She teaches,» she shrugged, as if unsurprised. «It seems to me that I can find answers to all questions in it, I just need to wait for the right chapter. Every time I open it, I find more and more new words and previously unseen images. I wonder how could I have missed this? And then I understand that the last time I was thinking about something else and I was worried about something else, that’s why these things did not seem important. In general, it’s nice: the book is like an old friend who does not get bored.

What do you want to learn from this friend? — the daughter graduated from the gymnasium, and it was time to find out if the girl dreams of further studies or plans to get married.

«You see, Dad,» Emma suddenly looked embarrassed, «I wish I could be strong enough to do things on my own. And not what my husband, father or state tells me.

This adult invention of Uwe did not surprise, but upset. His girl was going to live and, it seems, live not at all the life that he wanted for her.

«Well,» Osterman patted Emma on the shoulder, «my mother and I will try to get used to this idea. We have time to spare.

And a month ago, the time was up — Emma graduated from the thirteenth grade of her father’s gymnasium and had to decide where to go from her parental home: to the University of Baden, where they began to accept women for training, to agree with one of the local gentlemen, or to find a job in some shop…

Upstairs, the daughter paced her little room. Temporary calm gave way to springy activity that demanded an exit. Again and again Emma quoted from memory the letter now in the mail with a round postmark on the envelope «☆ Storkov ☆ –1 VII.17.06–»:

Your life’s work has already become a legend. Your triumph is a triumph of German character, German will and German technology. It is incredible what a person can achieve with the help of the elements. And although the natural forces cannot be changed or destroyed, they may well oppose each other. In order not to depend on air currents, a more significant force is required than the wind — and you have proved it. I ask you to honor and become such a force for me. I completed my studies at the gymnasium, graduated from the correspondence course in stenography, I speak French, Polish, English and Italian, I am not afraid of any job, even low: work in the kitchen, clean rooms or wash clothes. Please give me a chance to go through all the difficulties with you and be involved in your inspiring struggle with circumstances.

The letter was short. Emma rewrote it dozens of times until she was completely satisfied with the content. She didn’t want to look pathetic or crazy. The dream required realization and Emma did not come up with another option: you need to capture the wind that is. Let its impulses sometimes break and tear the threads, but everyone who sailed or flew a kite knows that if you catch your stream, it will lead you to the goal. Emma dared to write to a man who was both a hero and the laughingstock of the empire. Kaiser Wilhelm II is said to have called him «the dumbest of all South Germans.» But is it possible to confuse stupidity and stubbornness? Emma’s hero had a flexible morality and a strong spirit. His business failed more than once, but rose again and again like a phoenix from the ashes. «It is only natural that no one supports me, because no one wants to jump into the dark. But my goal is clear and my calculations are correct, «the Berlin Stock Exchange quoted the stubborn one. Emma was not at all afraid to jump into the dark: she was too young to weigh all the risks.

Numerous feet stomped in the corridor. The brothers rushed from the street at full speed: it’s supper time. The boys’ room was across the hallway and was the largest room in the house. It used to be the parents’ bedrooms, but when Lise became pregnant with her fifth, Osterman hired a carpenter who broke the partition between the rooms, and then, together with an assistant, arranged the boys’ beds and desks for classes. The couple moved to the first floor in the guest rooms, next to the pantry and dining room. Vilda huddled in the closet through the wall from Emma. Her sensitive Bavarian hearing more than once stopped the slightest fuss in the nursery at night. Twelve years later, the interior of the boy’s room has completely changed: the desks have disappeared, the bunk beds of the older brothers stood on the edge of the windows, Ivo slept on one side, and on the other, the bunks of Franz and Fritz shifted at an angle so that the twins could whisper head to head. A bookcase rose up to the ceiling between the windows, and in the center of the room stood a large round table, the former dining room, which was now used for study. It was forever littered with notebooks, pens, dry inkwells, and broken pencils. Vilda did not lose hope of recreating order on the table, but chaos defeated her aspirations again, and again, and again. Life in this room climbed from all the cracks, and there was nothing to be done about it.

Finally, Jacob’s footsteps were heard in the corridor. Emma could not confuse them — her brother walked with a cane. As a child, having been seriously ill with rubella, he received a complication on the joints. Arthritis exhausted the boy, twisted his right leg. The pain practically did not leave him, because the child early became tolerant of the trials that rained down on his head. At fourteen, Jacob was hardly taller than ten-year-old Henning, but in endurance and wisdom he could compete with his father. Emma opened the door and stuck her head in the doorway:

— Sent! she whispered into the gloom.

«Mom will kill you,» the twilight answered, and his brother quietly entered the room.

Jacob closed the door behind him and sank wearily into a chair. Dark whirlwinds gave the boy the appearance of a gypsy, and a calm and intelligent face — the appearance of an intelligent gypsy, almost an aristocrat. Emma kissed him lightly on the top of his head; she loved her brother almost as much as her father.

«Already killed.» Emma sat down on the bed with a sigh. We got into a fight as soon as I got back. I don’t know why she decided to find out where I was, apparently, intuition.

«Don’t confuse intuition with a good memory,» Jacob stretched out his bad leg and leaned his cane against the armrest. — The day before yesterday at Ivo’s birthday party, you blurted out that staying at your parents’ house is tantamount to imprisonment. And you, they say, are not a bird to sit in a cage. Well, now wait, birdie, when you are plucked.

«Come on, our mother never cared where we were or what we did. Vilda did more for us than she did.

However, she is a mother. And you are her daughter. And she has every right…

«… to pluck me,» Emma finished after her brother, «I remember. How did you get off?

— I was with my dad in the library, and the rest were playing football in a vacant lot. Klaus got his nose smashed with a ball, but I don’t think it’s serious.

«Vilda will kill you,» Emma repeated the phrase with the same intonation as Jacob. They both laughed, very much like it happened.

They paused, listening to the sounds of the street and the noise in the nursery. They did not need to speak, they understood each other from half a word and even half a thought.

— Are you sure? What did you do right? Jacob looked at his sister with intelligent blue eyes. He looked terribly like his mother, the same oval face, the same dimples on his cheeks. In a month and a half he will turn fifteen, and despite his lack of height, Jacob did not look like a teenager, a young man had already begun to form in him.

— I’m suffocating here. One and the same: study, home, friends…

— Me.

— Yes, you. Emma felt sad. But I’m not leaving for you. You know. I can’t live without air. The sky is everything to me. Well, not everything, — the sister interrupted herself, — but a lot. I love you, I love my father, but I cannot give my whole life to this love. I want to do something that the whole empire will talk about. I want to touch the great, really big and real, what will remain for centuries.

Jacob looked at her for a long time, then sighed and stood up:

— Well. You are a true woman of the twentieth century. And you are my sister, I will be proud of you anyway.

And left the room.

For dinner, they served thick pea soup with meatballs, large boiled potatoes sprinkled with small capers and poured with melted herbal butter, herring rollmops with gherkins, a salad of homemade vegetables that grew in the garden behind the house, the children waited for tea with the remains of the «wooden» pirogue. Actually, this is a Christmas delicacy, but on Sunday they celebrated Ivo’s birthday, and the birthday boy asked the cook Anna for it. Vilda dined with her family, looking after the twins. She sat at the end of the table, seating six-year-olds to her right and left. Of course, my mother was supposed to sit opposite my father, but in the Osterman house everyone had long given up on conventions — order at dinner was more important, and Vilda knew how to pacify the twins with one glance. So they sat at a long table: Uwe, Lise to his right, Klaus, Arnd and Fritz, Emma, Jacob, Henning, Ivo, Franz and Vilda to his left.

The weather Klaus and Arnd spent the whole dinner whispering about the last football match: how who scored, how who circled the defense, and how the ball flew right in Klaus’ face. Henning and Ivo, ten and eight years old, ate busily, quickly, apparently, they started to rush in the evening to the garden where they built a hut on a tree. The twins picked the herring and waited for the sweet to be served. Emma waited with a heavy heart for a conversation with her mother, her father read the evening paper, Jacob chewed, looking thoughtfully into the darkness outside the window, Vilda shushed at the children. Lise looked around at her family and sighed. This was the signal: the daughter put down her fork and exchanged glances with Jacob.

— Dear, do you know what your children did today?

«Hm-m-m-m…» Ove reluctantly looked up from the newspaper, but did not look up. «I suspect they were happy?»

«That’s how to say it,» Lise moved the newspaper away from her husband’s face with her hand. Your daughter is leaving home!

— Mother! I’m not going anywhere yet! Emma’s face flushed, her hands clutching the napkin in her lap. Jacob put his hand on them under the table, his sister now needed support.

— So. Where are you planning to go, honey? My father wasn’t angry, he was just asking. «And, most importantly, when did you want to notify your mother and me about this?»

«Dad… I just wrote a job application. And I don’t know if they will invite me or not. I don’t want to go to university, at least not now.

«In any case, the road to Baden-Württemberg awaits her,» Jacob interjected quietly.

— Married, as I understand it, you’re not going to? the mother jumped up.

«It seems to me that we have enough children in the house, why do you need grandchildren as well?» Emma said coldly.

Mrs. Osterman pushed her chair back with a thud, threw her napkin on the table, and reproachfully said to her husband:

— You will be silent?

She left the kitchen, slammed the door to her room, and there was silence. The younger children sat motionless. Vilda counted to fifteen and in a whisper ordered the twins to leave the table.

«Let them stay,» my father said sternly. Everyone should know what I’m going to say.

Emma straightened her shoulders and stood even taller. Her father never yelled at her. This is likely to happen even now. But the time has come to defend his own position, which means to hurt him. Emma didn’t want to hurt.

«No one would ever dare to talk to a mother like that. She gave you life. There is nothing more valuable than this. And even if you find her participation in your fate insufficient, this does not mean that your mother owes you something in addition to what she has already given.

Osterman’s voice seemed to cut the stones from the rock. He looked at his children carefully and sternly.

But dad…

— Shut up, Emma. I’ve never been hard on you, although I probably should have. You are my only daughter, and my mother and I put all the love we had accumulated into you when you arrived. Don’t be ungrateful.

— I’m already…

— I know how old you are. And I know what you want. You are free to do as you see fit. But we are still your parents. We are responsible for you and your brothers. We are responsible for the unity of the family. Even when you all grow up and leave this house, each of you will be connected to it by an invisible thread. This thread is called kinship. You should apologize to your mom. And then we’ll talk to you alone about the trip.

Emma hung her head. The boys looked at her with wide eyes. Vilda looked from Emma to Ove and tried her best to signal him to be gentle with her. However, Osterman did not see any of this. He looked at his daughter, at the parting of her wheaten hair, at her hunched shoulders. Uwe saw how Jacob gently squeezed his sister’s hand with his.

— Okay, dad. I’m sorry. Right now.

Like a balloon, the daughter was blown away and drooped.

«Go upstairs,» Uwe said in a tired voice.

Armchairs moved, clothes rustled, children silently rushed out of the dining room. Vilda followed the brood, looking back.

— Jacob, quickly into the room!

Jacob also stood up, leaning on his cane, and touched his sister’s shoulder as support.

— Good night, dad.

— Good dreams, son.

There were faint footsteps on the stairs. Anna had long ago stopped rattling dishes in the kitchen and went into the garden. Father and daughter were left alone.

— Forgive me, dad… I was angry. For mom. I remember how in childhood she played with me, braided braids, dressed up. I remember her hands. And the smell. And laughter. Where is our mother? Why did she stop being like this? Why did she stop loving us?

Ove was silent for a long time, then folded the newspaper, got up from the table and walked around the dining room. Emma looked at him furtively. She was sad and ashamed at the same time. The father returned to his chair, leaned against the back, looked at his daughter.

«I think she still loves us. Just reduced the intensity of love. Now, when she needs to pour love not only on you and me, but also on your seven brothers, it is obvious that the stream for each of us will become smaller and poorer. But that doesn’t mean it has stopped. Being a mother is hard work. And even if it seems to you that she does nothing: she just sits at home, then this is not so. You don’t see half of the care your mom gives you. You and your brothers. You don’t know fatigue yet, girl. You are strong, proactive, assertive. The only problem is that you are not wise.

— How to become wise, dad? Emma lifted her head and looked at her father.

«Unfortunately, it will happen on its own. And even more unfortunately, this will happen only with losses. Only pain teaches us wisdom.

«I can take the kettle off the stove with my bare hands!» Or hold your hand over the fire! How many say!

Ove took a deep breath.

— To become wise, you need to keep your soul above the fire… It happens that even physical pain does not add to the mind. But there are always losses. If you really want to leave home, don’t leave your mom with a broken heart. And, most importantly, do not keep such memories for yourself. Perhaps you will no longer have others — no one knows what awaits you at the other end of the journey…

Suddenly, Emma realized that tears were rolling down her face, that she was terribly sorry for mom and dad, and she felt sorry for everyone else. Poor she is poor, where does she climb, here, at home, it is warm and comfortable, why does she need this fight, because this is not her struggle. She would marry the son of a pharmacist or even a burgomaster, become a burgomaster’s daughter-in-law, give birth to children, gain weight, lure Vilda away… Emma cried and laughed at the same time.

— What are you? Ove was surprised. Of course, he met hysteria in women, but his daughter was distinguished by mental health. At least before.

— Bur…. Bur… burgomaster’s daughter-in-law,“ Emma gurgled, choking with laughter. „I imagined that I was the burgomaster’s daughter-in-law and that I took Vilda away from you. Dad, I’m afra-a-a-a-id… Suddenly he won’t answer… — Emma roared again, now at the top of her voice, giving vent to tears.

The father shook his head in surprise, took a linen napkin from the table and handed it to his daughter.

* * *

Three weeks later, when Emma had lost all hope and secretly began to study the brochure of the University of Tübingen in Baden, the postman brought an open letter. On the front side, a girl was sitting in a basket of roses. Lines stretched from the flower gondola to the airship of forget-me-nots, the young pilot cheerfully turned the steering wheel and smiled. The inscription was for some reason «Happy New Year!». There were several lines on the back: Dear Miss Osterman. You will do me the honor of accepting an invitation to work for the Zeppelin Group Airships. Ferdinand von Zeppelin.

— Vilda! Emma gasped. What time does the morning train to Berlin leave?

© oldthing.de

© oldthing.de

© oldthing.de

© oldthing.de

© oldthing.de

© oldthing.de

© oldthing.de

© oldthing.de

© oldthing.de

© oldthing.de

© oldthing.de

© oldthing.de

Chapter 2. To Berlin

Emma hurriedly packed her things, as if the Zeppelin had told her to start work at eight tomorrow instead of when. Stockings, pantaloons, day shirts, corseted bodices and stocking garters flew into the bag. Emma planned to ride in a travel suit, dark, but light, which was not afraid of dust or smoke. She took only two dresses with her: a brown training, simple, for every day, and dark blue, with puffy sleeves, for going out. The «happy» purple skirt, a pair of shift blouses, and a jacket were already in a small wooden suitcase. The rest of the clothes, including outerwear, hats, shoes, as well as books, care products and simple jewelry, Vilda will send by courier later. Between the lace and batik in the luggage was a book, carefully wrapped in brown paper and tied with twine. Father was silent for a long time at Emma’s request to take the Chronicle out of the house, and then replied — well, let at least something remind you of your family. The daughter thankfully kissed his hand and ran upstairs.

Jacob somehow turned gray, haggard. They had not parted with their sister for a long time, and what it would be like for him to become the eldest child, he did not understand. Vilda begged Emma to leave on the Thursday morning train so that Emma would have time to clean herself up upon arrival, and look around, and talk to her superiors. So Jacob had three extra days to collect his thoughts.

«I’ll write to you so often that I’ll even get bored,» Emma chirped, sitting with her brother on the bed and hugging him tightly.

«You won’t,» he answered judiciously and muffledly: his face was buried in his sister’s shoulder, «a new life will twist you.» At first we will receive a letter a week, then once a month, and then we will learn about your progress from the newspapers. After all, it is clear that your successes will coincide with the achievements of Zeppelin.

Emma kissed the top of his head, rocked him in her arms and was happy. Little lies did not bother her, because love is not measured by letters. Jacob foresaw a long separation and for the first time he was angry with his sister, although he did not show this anger. One evening Vilda found him in the dining room, thoughtful, hunched over, staring straight ahead.

«Isn’t it about you, young man, that it’s time for you to sleep, but you haven’t washed yet?» the nurse remarked sternly.

Jacob absently looked at her large face, tall figure, a true German: simple and energetic, and asked:

Vilda, are you leaving us?

Vilda Weber was attached to the Osterman children, but she shared her own life and that of her master. This simple question made her suddenly hot, causing Mrs. Weber to take on a crimson color that covered not only her face and neck in an even layer, but also her scalp, chest, back, backs of her hands and, it seems, even her calves. In a word, Vilda should have been lying, but she knew that the lie had already been noticed.

Widowed early, so early that she did not even understand her own status, Vilda found her own happiness in the Osterman family. Vilda’s husband, the handsome Martin, the day after the wedding, went from Timmdorf to visit his father on the farm, who fell ill and could not be at the wedding. He chose a short path, across the lake. The horse stumbled, broke through the not yet thick December ice of Dikze with all its weight and dragged its faithful owner along with it. Vilda, tall and strong, without waiting for her husband, the next day went through the snowdrifts alone, found a hole, returned to the village for help, waited until the peasants pulled out the mare and Martin, and then went home, tied a noose on the beam and hanged herself.

Saved, of course, the neighbor, as she sensed, ran after him. Vilda never cried about Martin, because it makes sense, but inside she had only emptiness and nothing more. A year later, Vilda went home to Bavaria, but on the way she saw an advertisement for a nanny in Storkov and decided that her stony face would not brighten up her parents’ days. I got off at the station, found a gymnasium, talked to Uwe, and got used to it. Sometimes something warm, quivering stirred in her, but she forbade herself to become attached to her pupils: everything will pass — this too will pass.

«Everyone will leave you someday, Jacob,» Vilda decided, «we are born alone and we die alone.» You must understand that your sister needs to take the next step. No one belongs to anyone, and you have no right to even pretend to blame Emma for her decision. When the time comes for you to make a choice, you will understand what I was talking about.

Perhaps Jacob tried to stay a little more cheerful these days, but his attempts were not very successful. Vilda, in her own way, felt sorry for the boy — he had suffered enough, but she remembered that God gives everyone a test according to their strength, and she could not make these tests easier for Jacob.

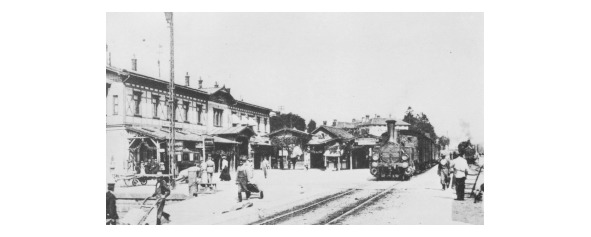

Trains passed Storkov four times a day: two in the morning and two in the evening. Departing from Grunow-Dammendorf, the trains reached Koenigs-Wusterhausen, and then turned to Berlin. The transfer in the capital will take time, so Emma decided not to delay and take the first train at 7:40. The farewell family dinner went on as usual: the twins were spinning like a spinning top, Vilda tried to give these mechanisms a static state, the middle children strove to finish the meal as soon as possible and go about their business — the school year began in a week and they, like all the children of the world, strove to take a walk and rest until the school routine swirled them. Jacob ate with concentration, my mother was lethargic, only my father broke the tradition and ate dinner without a newspaper. Emma felt impatience and responsibility before tomorrow, because of this she twitched, ate little and often glanced at the mantel clock. In the end, she decided on a demarche and asked to leave the table under the pretext of a baggage check before leaving.

In the room, Emma walked over to the window and let out a long breath. She was terribly worried that she would take the wrong train, lose all the money in Berlin or get lost herself in Friedrichshafen, the final point of the trip, not like the Zeppelin, or screw up on the first day of work. She was worried about what every person worries about before a responsible jerk. Her father gave her one hundred marks from the family savings, and she had twenty of her own, earned here and there on trifles from friends. This should have been enough for tickets to Lake Constance and the first month of work. The address of the shipyard was indicated on a postcard with a flower airship, Emma ran to the station the same day, looked at the atlas of railways, made sure that it was a decent ride — three days, and that’s not counting possible delays. The Zeppelin’s invitation was now wrapped in a book: valuable in valuable, the two things Emma held most dear to each other. On the evening of the first day, all on edge, she opened the Chronicle in the hope of finding an answer to the most important question now — will it work out? The soft pages swung open as silently as if they were woven. Glance caught

Winds, goddess, run before you; with your approach

The clouds are leaving the heavens, the earth is a masterful lush

A flower carpet is being laid, sea waves are smiling,

And the azure sky shines with spilled light 1.

Emma winced. Azure, winds, skies, sea waves. Well, okay, let not the sea, but the lake. This is too obvious a sign. She flipped back to the beginning of the chapter: thin Gothic letters formed into «An open secret for the benefit of people in need of knowledge.» The quote was definitely from the «Nature of Things» by Titus Lucretius Car — the poem was studied in philosophy classes, and no less accurately Emma had not read this chapter before. Laying the page with a postcard, she decided — I’ll figure it out later, when I have time. Goddess, you must. And smiled.

Now, looking at her hometown, she did not smile and even forgot to think about this strange sign. There was a knock at the door, and Emma shuddered in surprise and turned away from the window. Father came in, looked around at the mess in the room, the linen on the bed, the open trunks.

— Gathered?

Emma quickly approached her father, hugged him by the neck, as once a long time ago, in childhood, only now she was taller than him, albeit a little, but taller, and they probably looked strange. Ove’s heart sank, he put his arms around his daughter and whispered soothingly «well, well.» They stood like that for a minute, then the father pulled away, took her by the hands and said:

— When my mother and I just got married, I was happy, terribly happy and in love, but also terribly panicked. I had to leave my parental home and start an independent life. I didn’t know how everything would turn out, I didn’t know where we would live, I was sure of only one thing: without Lise, life would be incomplete. I want you to know that fear is normal. Only fools are not afraid. And even brave people are sometimes unlucky. You are very brave, but I don’t know how it will turn out. Just remember that you always have somewhere to return. And also know that I certainly believe that you are a fighter, that you will not give up from the first failure. Do not forget that you left this house for a purpose: to do something yourself, and not what your husband, father or state tells you to do.

Uwe smiled

— You remembered?!

— I remember everything. Every day of yours. Because I love you.

We got up early as usual. Anna, the cook, prepared a hearty breakfast for Emma — God knows when the child will be able to eat on the road, and folded several sandwiches in thick brown paper. Emma resisted as best she could, she considered herself quite an adult woman — she still didn’t have enough to mess around with snacks.

«Take it,» Father insisted, «you don’t have much money to spend on trifles.» This is the adult decision.

The traveler pouted her lips, but she took the parcel and put it in the bag on top. She planned to go to the station on a bicycle with a luggage basket.

«I’ll leave it with the caretaker,» she instructed Klaus, «and then you and the boys will pick it up, okay?» The brother nodded.

They began to say goodbye: Vilda led the children into the dining room, in a cramped corridor it would not be crowded. The twins tugged at their short pants and giggled. Emma kissed them and said — do not indulge! Ivo and Henning hugged their sister from both sides, received their kisses and raced upstairs. Klaus and Arnd, stretched out over the summer, in new sailor suits and breeches, looked at their sister intently. Emma hugged them one by one and shook them in her arms.

«Listen to Wild and Dad. — She stopped and added, — And my mother too.

The boys stayed. Jacob’s turn came, he thrust a small note to his sister:

— Read on the train. Of course, you will rarely write, but do not forget us, okay? — Touchingly squished his nose and leaned on his good leg. Emma put the folded square in the pocket of her travel jacket, squeezed her brother tightly, bent over his frizzy hair and whispered in his ear — I love you. She turned to Vilda, who stood at attention, almost as tall as Emma herself, and looked soulfully, as if proud of her pupil. She held out her hand to her and thanked her for everything. Vilda took a step back with the boys, making room for her parents. Emma went up to her mother, who looked at everything with a kind of absent look, sat down in a deep curtsy, stared at the floor and froze. Lise put her daughter’s hand on the braid folded in an intricate knot and whispered — well, go. Then she turned and walked through the dining room to her room. There was a soft creak of springs: Lise lay down on the bed.

Emma straightened up to her full height, turned to her father. He held his face with all his might, stood calm and even relaxed.

«Well, girl, all the words have been said. Do not be reckless, give yourself to the cause with all your heart. Ove held out his hand to his daughter as an equal, shook it. Emma had a lump in her throat, she wished she could, she couldn’t answer. From excitement she coughed, went out into the corridor. The family followed her. In the semi-darkness she put on her hat, opened the door, and the excitement suddenly subsided, as if dissipated along with the twilight. The sunny morning permeated the whole city, the bicycle bell was shining, people were walking in the distance about their business, a milkman boy ran past, the clock on the town hall began to strike seven.

«Time to go,» Emma said, and turned to her people. My father put the suitcase and bag into the bicycle basket, the brothers fell out into the street in a herd, Vilda stood in the doorway. «Time to go,» Emma repeated, getting on her bike and pushing off. It went slowly at first, then faster and faster. At the end of the street, she could not resist and looked back at the house: her relatives waved after her and smiled. Emma tinkled her bell in farewell and disappeared around the corner…

* * *

Emma drove to the station in about fifteen minutes, reached a familiar employee, Herr Lang (he really suited his last name: long as a pole, the same height as Emma, and dry as a reed), gave him a bicycle, asked him to keep it until the boys take away, pulled things out of the basket and went to the cashier. For two and a half marks I bought a third-class ticket to Berlin, found out that the train should arrive at the Silesian station at half past twelve. In the capital, Emma had to get to the central station and there transfer to a passenger one, and if you were lucky, take an express train to Munich, and from there again by train or with a post stagecoach to the town of Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance, on the banks of which stood the former shipyard, the current haven of airships and the ambitions of Count von Zeppelin. While waiting for the train, Emma took a seat at the office next to the station telegraph office. It was her idea to write the first letter before departure. She looked out the window, inhaled, exhaled, and scribbled fluently, rapidly on the yellowish sheet:

My dearest people! I’m at the station, waiting for the train. I got there normally, I left the bike with Lang. Daddy, don’t worry, the suitcase isn’t heavy at all. Dear Jacob, please don’t be sad. I’m sorry I took the Chronicle with me, I hope you visit me someday and can hold it in your hands again. Vilda, I’ll telegraph you the exact address after I’m settled, so that you can send things. Thank you in advance for your hard work! I feel inspiration and excitement, I hope that the first will help me, and the second will not hurt. Maybe in a year or two I will fly to visit you on an airship, then there will be a performance in the whole city! I hug you tightly and I beg you — do not be sad. I will try to write whenever possible. With love, your E.

She signed the envelope, handed it with a coin into a small window to the telegraph operator, who was turning the handle of a Siemens keyboard puncher, took her things and went out onto the platform. The big station clock showed seven twenty-five. The train was due to arrive any minute. Emma glanced back at the station building: a two-story building with an annex, baked red brick, with large arched windows and a tiled roof. In summer, the station was almost completely covered with ivy and wild grapes, which made the air smell sweet and intoxicating and the quiet hum of bees scurrying over this green mass. The brick was covered like a blanket, only with a strong wind did the living wall sway, here and there, revealing the red pieces of the old house. A little further away stood a white water tower with half-timbered partitions, austere and smart as a married lady. A flock of sparrows shot up from its roof, then in the distance there was a noise, a whistle, and a black glossy locomotive appeared, throwing clouds of white steam into the still cool summer sky. Slowing down, the train passed the waiting ones, lifting Emma’s hat prudently held by the wind, puffed, whistled and froze in place. A couple of doors opened and several people got out. Emma picked up her luggage, looked back at the station building one more time, and entered the carriage.

Exactly twenty minutes to eight the locomotive whistled again, jerked, and set off to the northwest. Emma looked out the window as the stationmaster watched the train, lowered his hand with the flag and closed the gate from the platform. The car was half empty, it still had to be filled with hard workers, farmers and ordinary people. Pushing things under the bench, Emma settled herself comfortably and prepared to watch: she saw a pair of swans with a brood flying over the Storkov Canal, how they turned around and gently sat on the water, graceful and majestic; then the village of Philadelphia flashed by; to the right and to the left floated meadows and trees, swampy backwaters and distant lakes. The train swayed, rushed forward, the white steam trail melted over the last cars and went somewhere back, towards the still low sun. If one could breathe with a glance, then Emma would now breathe deeply, inhale the images of her native land, imprint them like moving pictures in the Skladanovsky brothers’ bioscope. She liked everything: the long journey ahead, and independence that suddenly fell on her head, and the truce with her mother, and tobacco smoke from the boy who smoked in front, and the mustachioed uncle in the next row reading the morning newspaper. She turned back to see who was in that part of the car: there was an elderly Mrs. with a basket of vegetables and a bottle of milk, apparently visiting someone. The old woman smiled at the girl and again began to look out the window. Something rustled in her jacket, and Emma remembered that her brother had given her the note. She pulled out a small square from her right pocket, unfolded it, recognized the familiar handwriting, rounded like her mother’s, and ran her eyes over the lines.

Emma, you are the most airy, heavenly and light person I know. You are the wind itself. I often remember how I was still healthy, and we ran with you to the mill, climbed our oak and looked at the stars until late in the evening. Do you remember how mother then chased us around the house, and we laughed and hid behind father? Then I dreamed that together we would conquer this sky, make wings and fly away. Thought about whether Icarus had a sister? Did she support him or, on the contrary, dissuade him? Don’t know. But I looked at you these weeks and saw another sister, Emma of the future. You are like Frederick of Anhalt-Zerbst, who conquered the whole country and became truly the Great Ruler Catherine: you are rushing somewhere into the unknown, as dark as the night sky you love, you are not afraid of loneliness and you do not look back. I am almost sure that you will forget to read my letter on the train, because you will be captured by the spirit of travel and change. Well, I hope you find it sooner or later. I wish you to keep in the upcoming battle (it is unlikely that you will be satisfied if the future is given without a fight, right?) Faith in yourself. Try a second, third and fifteenth time. Take a break and get back into the fight. Conquer your heights methodically and persistently. No one will take them apart from you. Hugs, Jacob.

Swaying on the hard bench, she read the note three times. Folded, held in her hands. Then, without looking, she put it in her left pocket and suddenly found a coin there. Emma stuffed all the money into her modest belongings and put a little in the inside pocket of the belt on her skirt, just in case. There was no money in the jacket in the morning. She took out a coin, it was twenty gold marks. The Kaiser on tails looked out the window at his empire, proudly spreading his wings an eagle under a crown on the reverse — at the uncle still reading in the next row. If Emma had not been a well-mannered girl, she would certainly have opened her mouth in surprise. Having suddenly increased her own fortune, she felt only shame. The money, of course, was secretly planted by Uwe. And she turned out to be an ungrateful brute who didn’t give her father the attention he deserved. Now Emma wanted to turn the train around and then run for a long time from the station to the house to hug her father and cry about what was left behind: care, love, endless parental patience and much more. First her heart sank, then her hand clutched the coin, and Emma whispered to her faded reflection in the glass: Dad, I won’t let you down.

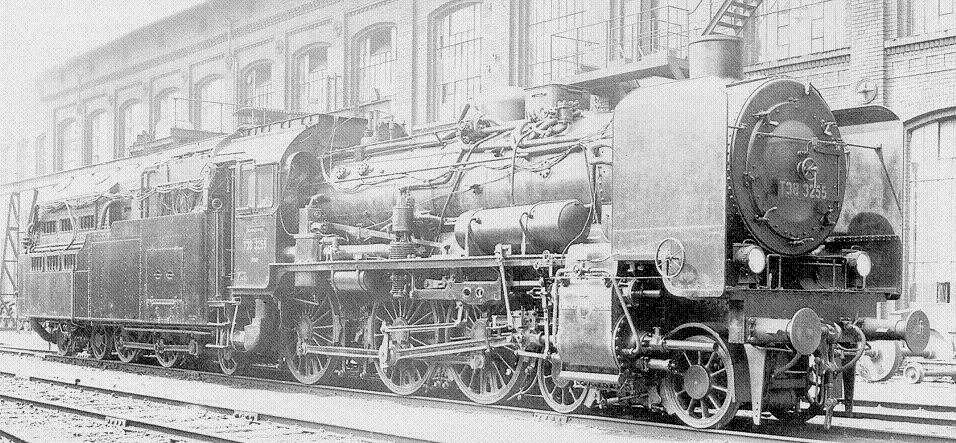

The train was moving under its own power, not particularly accelerating, carefully, as if carrying eggs to the royal table, stopping where it should, starting off again. The car gradually filled with people and tobacco smoke, but there were still empty seats. Finally, a smooth blue expanse appeared to the left — the train was approaching Lake Krupel. This means that the middle of the path is approaching, Koenigs-Wusterhausen. The sun rose, turned white, turned around in the blue sky. So far, it was floating behind the tail of the train, but Emma knew that after Wusterhausen the star would crawl into her window, begin to blind and fry all the way to Berlin. Emma discreetly unbuttoned her jacket and prepared for the torture.

Finally reached the end station of our railway line. In Koenigs-Wusterhausen, people filled up, although the time was late, ten hours. Aunts brought children and food, merchants, artisans, doctors, in a word, philistines — each his own: suitcases, wooden boxes on a belt, bags of goods. The new arrivals seated themselves noisily, the conductor opened ventilation holes in the ceiling with a long stick. A decent-looking gentleman in pince-nez, either a pharmacist or a teacher, sat down on Emma’s bench. She gave a short nod, moved closer to the window and hugged herself imperceptibly around the waist, covering her left pocket with a letter and her father’s coin. As people say, caution is the mother of wisdom. Time went on as usual, the train moved, Emma stared out the window. She no longer regretted that she had sat on the hot side — all the way to Berlin, rivers and lakes shone on the right: Dahme, Krumme, Langer, Spree. The girl looked at houses and railway stations, gulls hovering in the piercing blue sky and white herons taking off from the lake surface, alleys of trees hanging over the river, and swift swifts that cut the air with wings like knives. She especially remembered the graceful storks, a symbol of her hometown, who stood in huge nests and clicked their red beaks after the train, as if wishing Emma good luck.

They arrived at the Silesian railway station punctually, at eleven-thirty. They fell out onto the platform together, with the whole composition, as if they went like this every day. Emma stomped a little at the tail of the line, a decent mister in pince-nez helped her carry out the suitcase, received a well-deserved thanks and left. The glossy black locomotive whistled goodbye, doused Emma with steam, and fell silent. She stood enchanted in the middle of the platform, preparing to take the first step towards her dream. A porter ran past and offered to help. Oh no thanks, Emma thanked her as she grabbed her luggage and finally moved on.

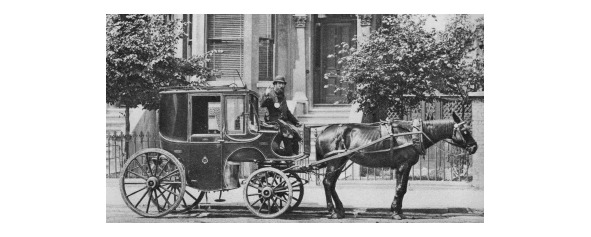

The first East Station was closed five years before Emma’s birth. Her father told her that it was grandiose, like a palace: solid, but at the same time impossibly airy, all lacy and as if striving upwards. The second East Station was originally called Frankfurt, but after the closure of the first, it became the main railway junction for all trains that ran in west-east directions. Together with the reorganization, the name was also changed, now the station was called Silesian. The building had simple and seemingly even chopped forms, with wide front entrances and massive columns. At the ends there were two modest turrets, not anyhow high, with low teeth and imperial eagles on long peaks. Emma wanted to stretch herself after a long sitting, but she was afraid to miss the train, so she took a cab and asked to be taken to the central station.

— On which? he clarified. Emma hesitated. — Where are you going to go?

— Lake Constance.

The driver whistled indecently:

— Too far. You need to go to the Potsdam station, fraulein, sit down. We’ll get there with the breeze, it’s not far.

Emma was in Berlin only once, when she was a child. In August 1892, before the school year, Uwe decided to take his family on a short trip to the capital. Lise was pregnant with Klaus, but the period was short, the child had just appeared under the dress. She felt great, laughed all the way and hugged the children, Uwe was happy because she was happy. Emma and Jacob pinched, giggled, climbed first on the benches on the train, then, like little monkeys, after their father. In Berlin, they walked in the parks, Jacob was about to turn a year old, so Uwe carried him in his arms all the way. Emma walked between her parents and held their hands. Sometimes she tucked her legs up and did «eeeeeh!», which made Uwe and Lise laugh, rock her with their strong hands and put her on the ground. Quiet, please, father asked, mother must be hard. But Lise laughed again, kissed Uwe on the cheek, stroked the weary Jakob on the head, and moved on. They ate something terribly delicious in small restaurants, took Emma for a pony ride, bought her candy. All that day Emma remembered as one continuous cloudless happiness. On the evening train they returned home, both children fell asleep on the way. Uwe carried his daughter, curled up on his shoulder, Lise, her son, and quietly whispered to her husband: I love you so much. He kissed her on the nose gently so as not to wake Emma, and they walked on.

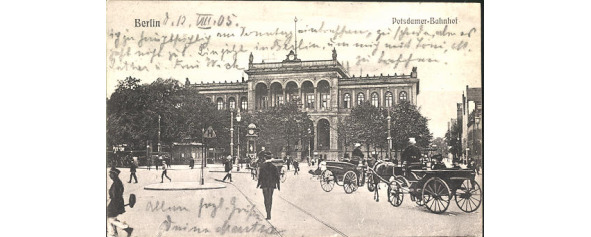

Now Emma was driving to the landau and did not recognize the city. Well, first of all, she just didn’t remember him. Secondly, she did not know if she and her parents had been in this part of town the last time or not. Thirdly, after all, fourteen years have passed since 1892, it would be strange if the capital had not changed. Horse-drawn carriages overtook cars. Electric lanterns adorned the wide stone pavements. Elegant ladies walked along them with equally elegant gentlemen. Emma stared at the outfits, the wide-brimmed hats, the tight shoes peeking out from under the skirts, the lace parasols from the sun: more than ever, she felt like a mess who accidentally entered a fabulous ball. Well, let, Emma thought, my time will come — I will also walk in chic outfits. She felt in her pocket for the note and her father’s money, which gave her self-confidence. When we passed Potsdamer Platz, Emma was taken aback by the number of electric trams. She could not even imagine it: there were dozens, maybe hundreds, the rails branched like lines on her arm. Frightened horses neighed, bells strummed, carriage drivers shouted, people ran between trams, wagons, cyclists and horse-drawn horses. The Blessed Virgin Mary, Emma exclaimed to herself and closed her eyes just in case. However, the driver was an experienced man, he calmly maneuvered between the cars and scurrying people, banging, nagging, snapping his whip, and he took his passenger out of this bedlam. We rolled a little more and stopped. Emma opened her eyes: they arrived.

The building of the Potsdam station, as it seemed to Emma, was smaller than the Silesian, but many times more beautiful. Arched, light, with a large clock on the pediment, it seemed to breathe with all its architecture. In front of the exits, there was a wide square, surrounded by alleys around the perimeter. She asked the employee how to get to the cash registers, took a wrong turn a couple of times, got on the right track, and took a queue at the window. Hunger had been sucking in her stomach for a long time, and Emma was glad that she had agreed to take sandwiches on the road.

— Good afternoon. Which direction? The middle-aged woman looked at Emma attentively, even in a motherly way.

— Hello. Actually, I need to get to Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance. Is it possible to get there without transfers?

— Absolutely no transfers will work. You can take a three-hour express train to Munich, then transfer to a regular passenger train to Lindau, and then along the branch line to Friedrichshafen. Buy tickets from us, transfer passes will be valid.

What if the express is delayed?

— After Munich, I will issue you tickets with an open date, do not worry.

— Be so kind as to write out then on the express train to the second class. Ladies compartment or single. And you can get to Friedrichshafen by third class.

The ticket attendant rustled the papers, put a stamp on three cardboard boxes:

— Sixty-two marks.

Emma took coins from her bag pocket, counted them out, then added change from her belt. She took a cardboard box in the window, smiled.

— Thanks!

— Bon Voyage. Next one please.

Emma stepped away from the registers, exhaled. That’s it, the Rubicon has been crossed. The clock showed the beginning of the first. There was enough time to clean up and rest a bit. First of all, she checked her valuables in her pocket: both the note and the coin were in place. Here you go, Emma thought, and patted her pocket lightly. Then she made a trip to the ladies’ room, visited the water closet, shifted the money from the suitcase to the bag, rinsed her face, caught her breath. Am I going? she thought, looking at herself in a large copper-framed mirror. You go, you go, — the reflection answered her. Emma smiled. Phew, just like an adult! And you are an adult, «the reflection answered her. Emma put on her hat playfully and stepped out into the hall. There was a booth in the corner with the sign «Lemonade, water, fresh beer.» Emma bought a glass of lemonade, drank it in one gulp, and asked for another. The second drank for a long time, stretching and savoring. She went to the nearest shop, took a brown bag out of her bag, and untied it. Inside, sandwiches were neatly stacked, each wrapped in translucent oiled paper: cheese, salami, ham, capers, and even a rhubarb jam sandwich. Anna carefully signed each packaged sandwich with a carbon pencil, which one went with what, so that the owner’s daughter would not have to dig through the paper. Emma sat down on a bench, stretching her legs with pleasure. Oh, how sweet, she thought, sinking her teeth into the ham: the meat might not last the next five hours. So she ate two more sandwiches, putting aside only the most reliable ones: with cheese and salami. Finishing a sweet sandwich, Emma spotted a poster stand in the square. She had to keep herself occupied until half past two, with about two hours to spare. She left the suitcase in the inventory room, received a receipt and went outside.

The station square was noisy, cars honked, horses rattled their harness in anticipation of riders. The poster was large, half a pedestal.

Variety show

APOLLO THEATER

By popular demand from viewers

«LADY THE MOON»

one-act fantasy operetta

with parodic inventory

Location: Berlin, Luna

Music: Paul Linke

Libretto by Heinz Bolten-Beckers

Every Thursday and Saturday.

Find out the schedule of performances at the box office.

Theater of Special Opportunities and Dignity.

As well as gardens with magnificent illumination

Friedrich Avenue 218, Berlin

Emma looked around, saw the janitor, called out.

— Dear, how far is it to the Apollo Theatre?

«No, it’s close by, about a mile away,» he took off his cap and wiped his forehead. — Go straight along Leipzig Street, after two blocks turn right and another block. And then ask, so as not to pass by.

Out of habit, Emma sat down briefly in her curb, thanked her, glanced once more at the station clock: it was twelve thirty-five, tightened her grip on the handle of her bag, and set off in search of spectacle.

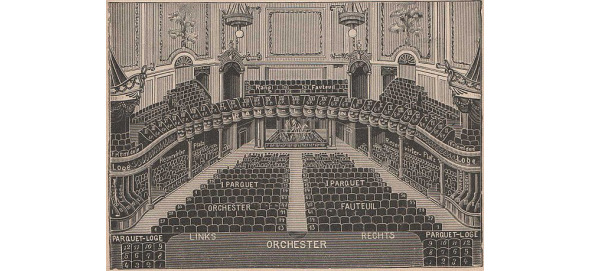

Variety show Emma found quickly. It was an outstanding five-story building with bay windows and turrets. On the facade of the third floor, a dancer and a violinist were painted on the edge of the window. There were also drawings upstairs, but Emma’s hat was already in danger of falling onto the pavement, so she resolutely stepped under a giant round awning that said «Apollo’s Theatre.» It was cold and sparse inside. She looked around for the usher, went up to him. I learned that there are performances, and even daytime ones, and moreover, the next one will begin in fifteen minutes. Emma bought the cheapest ticket at the box office, received the program, found out that the performance was going on for about an hour and a half, calmed down that she had time to get to the station, and only then went up to the gallery. It was almost empty here, the entire audience was mostly seated in the stalls. The girl carefully placed the bag under her feet, leaned back and fixed her eyes on the orchestra. About twenty people were sitting there, the conductor marked something in the score. Gradually they gave three calls, the lights went out and something unimaginable began on the stage.

Mechanic Fritz Steppke rents a room from the widow Pusebach. He is engaged to the widow’s niece, Maria, and is also obsessed with flying and other planets (at this point, Emma blushed deeply in the dark). One night, he secretly flies to the Moon in a balloon, but since the phantasmagoria on the stage was already off scale, it was not clear whether what happened next was only Steppe’s dream or reality. The Shooting Star Prince is in love with Lady Moon. But a mechanic flies to that one, and she leaves her boyfriend. The manager of the Moon, Theophilus, recognizes his former love in the widow Pusebach, but considers her a mistake. In the next aria, he falls in love with Luna’s maid Stella, and the tax inspector Panneke begins to chase after the widow. Couples rotate like stars in the night sky, change places, passions, and, as expected, before sunset, return to their original places. As a result, each pot finds its lid, Steppke realizes that the attic apartment is no worse than Luna, returns to the family, and his fiancee Maria finds him a job as the first captain of Count Zeppelin’s airship. At the last aria, «This is the air of Berlin,» Emma jumped up from her seat and gave a standing ovation along with the audience. And the music captured her, and the performance, but the main thing, of course, was in the signs. Flying! Zeppelin! It just can’t be!

— Bravo! yelled the hall.

— Bravo! Bravo! Emma echoed.

The artists bowed, the conductor applauded the orchestra, tapping his baton on his open palm. The applause continued for several minutes, finally, the artists disappeared backstage, and Emma collapsed back into her chair. This show turned her around. It cannot be that in the morning she ate an omelette at home and was afraid not to get there or get lost. It turns out that this is exactly what you need to be afraid of: that every day scrambled eggs and never — theater, flight, conquest. Oh, how delighted she was. The music sounded inside, I wanted to spin right here in the gallery. Emma picked up her bag and ran downstairs, swinging it rhythmically to the music in her head.

* * *

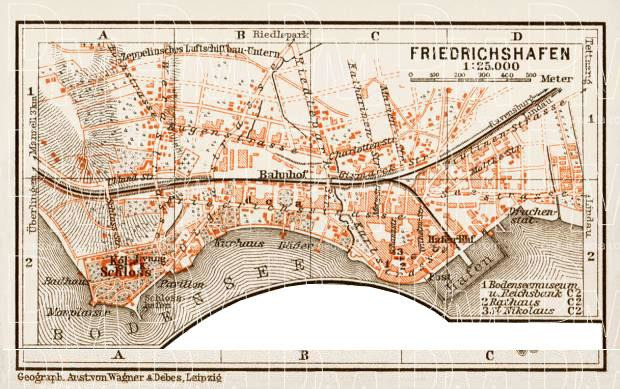

The whole trip to Friedrichshafen, the operetta did not let Emma go. «This is the Berlin air, this is the Berlin air,» she hummed to herself, leaning against the frame of the window in her compartment. At the transplant in Munich, Emma sent home a long letter, written in advance, in which she told her father and brother about the trip, and about the capital, and, of course, about going to the theater. Late Saturday night, at exactly eleven o’clock, Emma fell out of the train at Friedrichshafen station like a sack. The last crossing was the most difficult — almost two hundred kilometers in third class, she would not make such a mistake again. By telegraph, Emma sent a message home that she had arrived safely, marked «deliver in the morning,» then she rented a cheap room at the railway station hotel, because it would not be too smart to go at night looking at the shipyard. She had thirty marks left, plus her father’s twenty. For some reason, Emma didn’t want to spend it, as if it were a direct link to the house. Having somehow undressed and not washed at all, she fell on the bed and instantly fell asleep.

The maid woke Emma early in the morning. Before a responsible meeting, she wanted to check everything again and put herself in order. She put on a «happy» skirt, a white blouse. She braided her hair and threw it behind her back. I cleaned the hat from dust and only then put it on. She checked her belongings to see if she had forgotten anything: the book was still in the bag, packed in paper. On top of it now lay the libretto of The Lady of the Moon. Went downstairs, went outside, looked around. She called the driver, who spoke in a Swabian dialect, as if he were mumbling or lisping.

«Do you know where the Zeppelin house is?»

Who doeshn’t know. On the other shide, in Girshberg Castle.

— Oh! — Emma sat down in horror, imagining a new journey now to Switzerland, so that somewhere there, in the unknown castle of Girsberg, to look for a Zeppelin, spend all the money and, of course, not find it.

— Why are you scharing my filly. Don’t be afraid, I’ll take you to the count.

«Where is he?»

— We know where, in our shedsh.

— What sheds? Emma rolled her eyes.

— Oh, shit down already! Move on, honey!

The filly snorted and ran lightly along the pavement.

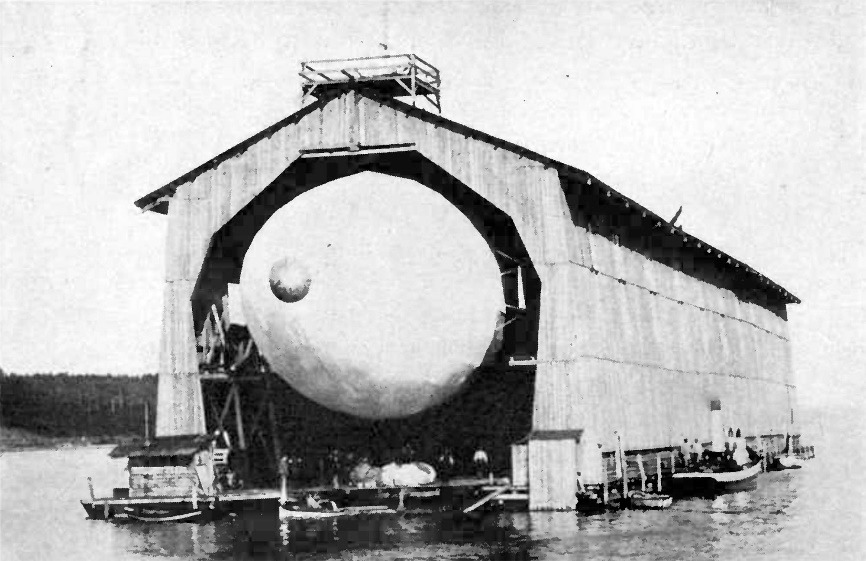

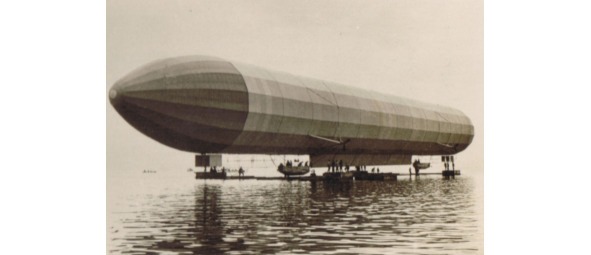

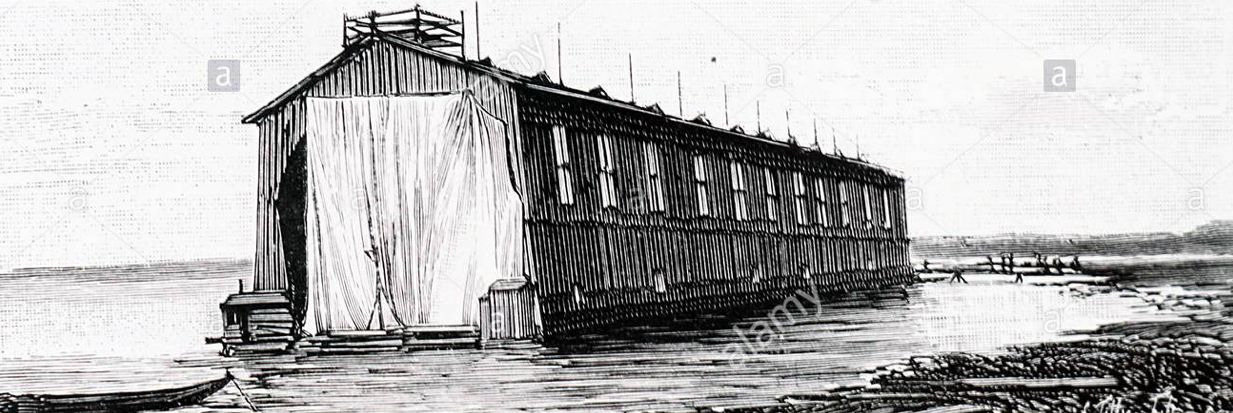

In Manzel Bay, on the shores of Lake Constance, there was a huge hangar. Despite the early Sunday morning, people were scurrying about here and there. They glanced at the girl with curiosity and ran on about their business. Emma asked the driver to wait in case the Zeppelin was not «in the sharays». She hesitated in embarrassment in front of the shipyard, lowering her simple belongings to the ground. A squat figure stepped out of the building in the distance. The man walked along the footbridge measuredly, calmly, looking at the sky. I saw a wagon, then a girl with luggage. It accelerated a little, but it went on just as thoroughly, as if it were hosting a parade. It was Ferdinand von Zeppelin.

© akpool.de

© picclick.de

© koenigswusterhausen.de

© forum.modelldepo.ru

© ma-shops.co.uk

© wikimedia.org

© peterberthoud.co.uk

© oldthing.de

© oldthing.de

© wikimedia.org

© pinterest.com

© wikimedia.org

© stadtmuseum.de

© wikipedia. org

© alamy.de

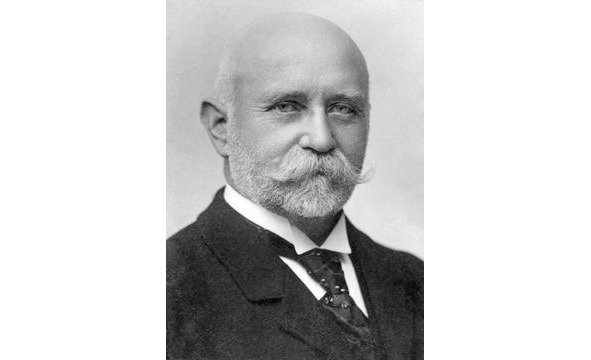

Chapter 3. Count Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August von Zeppelin

The hospital chapel was quiet except for the candles crackling on plinths draped in black cloth. The coffin was buried in greenery, it was solemn and elegant. There was a kolbak on the lid, the light shimmered on the fur softly, as if comforting. A woolen aurora cord passed through a cockade with an embroidered eagle and went down with a brush down to a stained tree. The feather sultan bristled cheerfully, as if the owner of the hat were not lying cold and insensible to the grief of the people gathered here, but was driving at full speed on his beloved trotter towards the enemy. Behind the coffin stood a white marble bust. The Munich sculptor completed it a few years ago, when people came to the aluminum plant in Lüdenscheid and the city came to life, flourished, and grew. Wreaths with mourning ribbons leaned, as if heartbroken, to hug the deceased for the last time, console and say goodbye. There was a chair next to the coffin, now empty. The widow became ill, and the sister of mercy took her away to give drops.

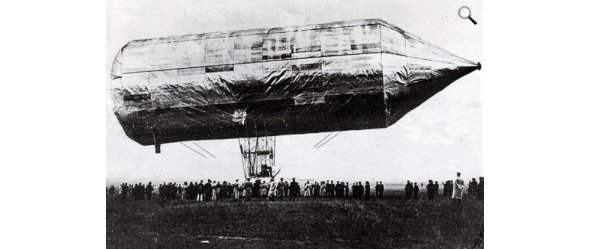

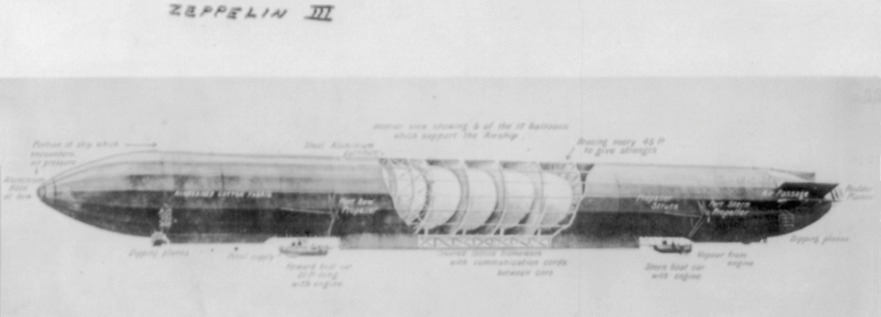

Zeppelin arrived at the hospital of St. John the Baptist in Bonn an hour ago. Their relationship with Berg was complicated, but strong. Common interests, the desire to make a breakthrough united these people, gradually rubbing against each other over the years, linking them with invisible ties of the need to do everything in the best possible way. Engineer, industrialist, commercial adviser to Kaiser Wilhelm II, Karl Berg plunged into the innovative theme so closely and successfully that he reorganized his great-grandfather’s button production into a metalworking holding. He bought an iron plant in Eveking, a hammer mill in Werdol, copper smelters in Berlin and Aussig, started working in the electrical industry, realized the advantages of aluminum as the best material for construction. Having learned from his Russian stepfather in 1892 that engineer David Schwartz had decided to build the first all-metal airship in Russia, Berg took over the financing and execution of the project, and delivered the aluminum frame and parts to the assembly site in St. Petersburg. It turned out, as in the saying: the beginning was not a masterpiece, and until the death of David in the ninety-seventh, Berg struggled with the implementation of the aircraft. Schwartz’s widow, Melania, turned out to be really stubborn, and continued her husband’s work. When Zeppelin met Berg in November 1897, Schwarz’s airship managed to climb four hundred meters. However, weather conditions at Tempelhof were unfavorable, and the belt drive and lack of dynamic steering were serious design flaws. Four propellers, one under the nacelle hull to lift the ship up, a second at the rear of the basket for forward propulsion, and one on each side of the hull for steering, were driven by belts over rimless drive wheels. A strong wind tore the belts from the pulleys, and the airship, left out of control, collapsed to the ground.

Berg had a contract with Schwartz under which he undertook not to supply aluminum to any other airship manufacturer. To continue the topic of airship building, Berg agreed to a meeting with Zeppelin, and as compensation for the termination of the contract, he paid Melanya Schwartz twice the amount agreed. Newspapers called it a «patent war», but there was no time to prove that the Zeppelin airship had a completely different construct.

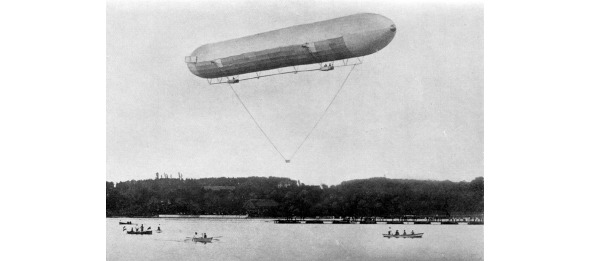

To finalize the design, von Zeppelin discussed with Berg the design of an improved ship, and already six months later, in May 1898, together with Philip Holtzmann, the one who built the Reichstag, the count created a joint-stock company for the promotion of aeronautics. Half of the capital, four hundred and forty-one thousand marks, Zeppelin invested from personal funds. In July 1900, from a floating hangar in Manzel Bay on Lake Constance, the count managed to launch the airship LZ 1 into the sky, but after eighteen minutes, due to a trimmer failure, the first-born had to be landed in Immenstadt. Zeppelin tried three more times, in October, and, it seems, even successfully, but every time there were overlaps: either the wind would fly in, or the gas tank would flood. The transport inspector rated the prototype quite highly, but refused to consider it as a commercial or military vehicle. After this fiasco, the shareholders were reluctant to invest, or even completely withdrawn, because the company’s torment dragged on for some more time, but at the end of the same year the joint-stock company was nevertheless liquidated.

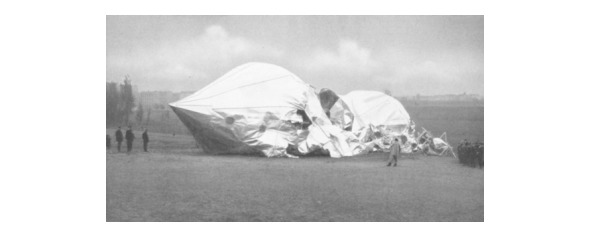

Zeppelin made the decision to dissolve the company with a heavy heart: the team had to be fired and the LZ 1 sold as scrap. Berg continued to experiment with metal. In Schwarz’s airship, he used his own alloy — aluminum «Victoria», in the zeppelin — pure aluminum. In 1903, the metallurgist Alfred Wilm turned to the Carl Berg plant with a request to test his new alloy in an industrial design. Wilm found that if aluminum with a small percentage of copper at a standard quenching temperature is first cooled sharply and then placed at room temperature for several days, then it will «ripen»: it will become stronger and stronger and at the same time retain its former plasticity. Wilm called the new alloy duralumin. Zeppelin immediately wanted to use it in the work, but a huge number of technical difficulties arose, which to this day have not been solved. Therefore, for the new zeppelin, Berg used a combination of aluminum with zinc and zinc copper. Used it but didn’t see results. In November, when LZ 2 was being taken out of the hangar and prepared for launch, a storm gust hit the airship against the wall, it fell nose into the water, both engines were torn off and the uncontrollable ship was carried right to the Swiss coast. While they were repairing for two months, Berg fell ill, and von Zeppelin spent the January start without a faithful partner.

Seven-month-old Herbert, Berg’s youngest son, hummed in his nanny’s arms. The eldest daughter Helen blotted her tears under a black veil, her husband hugged her by the shoulders and whispered something soothingly. The face of Berg’s son-in-law, Alfred Colsman, was intelligent and slightly pockmarked. The head was adorned with the first bald patches, and the face was famously twisted mustaches. He was a head taller than the Zeppelin who sat behind the family in the hospital chapel. The count recalled the last conversation with Berg, which resulted in a fierce argument. The owner of the concern made it quite clear that he wanted to play a leading role in the development of airships. Zeppelin, for obvious reasons, did not like this situation. Nobody wanted to retreat, but both understood that without each other their cause would not move forward. Berg had industrial possibilities, Zeppelin had his own inventions and incredible energy. Pedantic and courageous, both with a baggage of incredible ideas, they were careful with each other and at the same time they were mutually attracted. With whom to do business now, Zeppelin did not know. The count listened to the crackle of candles, stared blankly at the coffin in which his partner rested, and wondered if he was now saying goodbye to his own dreams…

The next day, they were already buried in Lüdenscheid, in the Berg family tomb. The funeral home delivered the deceased there in a hearse, the family and relatives returned from Bonn in the evening. The high May sun shone joyfully through the greenery, as if mocking the grief of the people who were walking in a mourning column. Everything was black: black horses, a lacquered carriage, a coachman in a coal camisole, men’s hats and weightless mourning veils, only the scarlet velvet pedestal under the coffin hurt the eyes, wreaths of burgundy roses, and red bandages on the horses’ legs. The family crypt is located in the Protestant cemetery on Matilda Street. From the entrance we went to the left for another hundred steps. Mrs. Berg’s legs gave way, so her son-in-law and a stranger in a monocle, unfamiliar to Zeppelin, held her by the arms.

When it was all over, they slowly made their way to the exit. At the gates of the graveyard, the count approached the family, once again expressed his condolences. He recalled for a moment his son-in-law, towering over the drooping women like a pillar, introduced himself.

— Mr. Colsman, I apologize that I am addressing you at such an inopportune moment. Your father-in-law and I had something in common…

«Yes, Count,» Alfred nodded, «I know.

— Until it is announced who will conduct the business of the company, I will have to freeze work on new samples. All I ask is that you inform me of the family’s decision when a manager or a new CEO is appointed. The Zeppelin handed Colsman an address card.

— Father-in-law asked me to head the concern. The aluminum plant in Verdol, which is part of the holding, belongs to me. Got it from my father. We talked with Berg in the hospital, discussed plans. He knew that he was dying, so he called the executor and made a will. If you give us some time to get the family affairs in order,“ Colsman nodded briefly towards the ladies, „I will study the project documentation and contact you.

— Will wait.

The Zeppelin shook hands with Alfred Colsman and departed for the station.

* * *

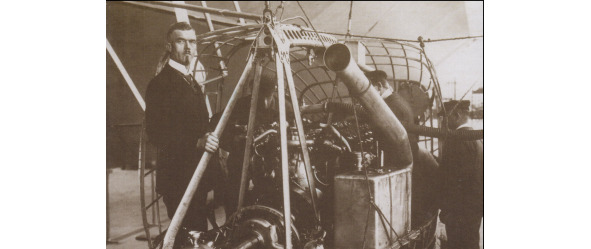

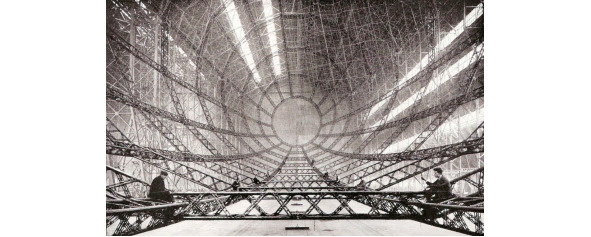

Six years ago, when the property of the joint-stock company was put up for auction in connection with bankruptcy, the only way to save the project was through personal investment. Zeppelin had no choice but to acquire a plot of land donated to the joint-stock company by King Wilhelm II of Württemberg, hangars, all workshops, machine tools and even the airship itself. The faithful Dürr bought the rest. Ludwig Dürr von Zeppelin met at the design office of the German Association for the Promotion of Air Navigation, he was still a student at the Higher School of Mechanical Engineering in Esslingen am Neckar. The mind and loyalty of this man conquered the count, and at the time of the collapse, it was Dürr who remained the only employee of the company — to lose him for Zeppelin meant betraying his own ideals. There were times when a designer worked without insurance or even a salary, lived in a hut on the lake, worked in the most Spartan conditions. Dürr never doubted his boss. It was then that he showed the count his own development — an innovative light-type design, which became the basis of all future Zeppelin airships.

Now the ship had two Daimler 85-horse motors that drove four three-bladed propellers, the keel became more stable, and the two elevators had a larger coverage area than the LZ 1. To reduce gas permeability, two cotton sheets were taken for the shell, between which laid a layer of rubber. The design was divided into sixteen compartments and the frame system was improved.

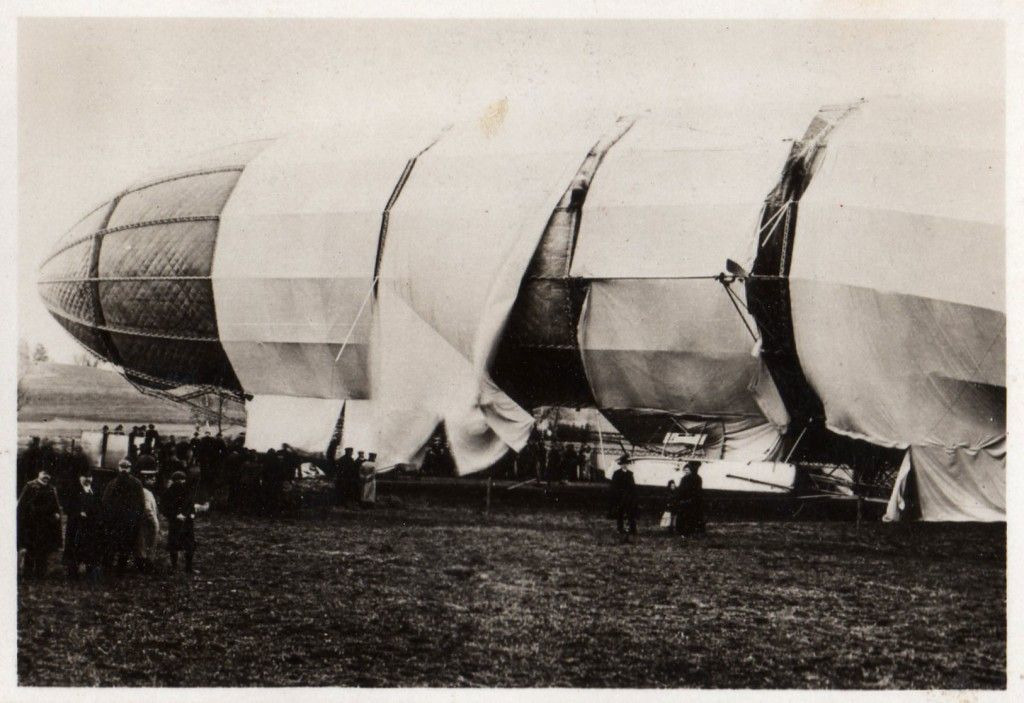

On the launch day, January 17, there was a strong wind, and the airship could overcome it if it had time to rise above 450 meters. The ship reached a four-hundred-meter height, and then the gust first damaged the side rudder, then the Zeppelin realized that at first the right engine turned off and did not respond, and then the fuel stopped flowing to the left. It was not easy to land a 128-meter ship between the mountains in the Allgäu: the count released gas from the chambers, anchored right in the field, the gondolas hit the frozen ground and the airship hull fell on them. Farmers came running, pulled Zeppelin and Dürr out of the cabin. They dragged heavy stones from the nearest mountains, fixed instead of the anchor torn off by the wind on the bow and stern of the airship. This killed him, but who knew. At night, the wind turned into a severe thunderstorm, and the fixed ship shook so that the shell was almost completely torn off, and the engines and frame were dented into rocky ground, so the only thing left to do was to give the airship for remelting.

The despair did not leave for a long time. For the first time, few followers of Zeppelin saw him in such a state: ready to give up what he loved. Here, too, the newspapermen seem to have broken the chain. Two devastating articles by some Eckener appeared in the Frankfurtskaya at once: on January 19 — «A New Attempt to Travel by Count Zeppelin» and the next day — «The End of the Zeppelin Airships». And the most unbearable thing is that this hack was right about almost everything. The Zeppelin threw the paper on the table, twirled his mustache angrily, and thought about what to do. Did what he always did. I talked with Isabella, she pawned some of the jewelry, the count added his own, and the family capital decreased by another hundred thousand marks. The Kaiser and the War Ministry once again turned their backs on the failed eccentric. Only the sovereign, the king of Württemberg, continued to believe in the count and covered the Zeppelins with another money lottery for a loan for new construction. Perking up and remembering the army past, in one of the conversations with his comrades-in-arms, the count decides: «In the name of God, let’s start from the very beginning.» And they started.