Бесплатный фрагмент - Tiflis stamp

Tiflis stamp is an amazing journey of the extraordinary mark through the time, the country and people’s lives

What this book is about

The people’s fates are sometimes formed very surprisingly and even fantastically. The history of countries and peoples develops even in a more complicated and contradictory manner. And in this circulation of events, the small objects around us, sometimes become the most vivid reflection of the changes occurring in the world and in time.

Modest miniature — a postage stamp is the best confirmation of this idea. Each stamp is a reflection of the time and the state where it was born; of the events that preceded its appearance. A postage stamp is a witness of history, culture and life of countries and peoples. It is the connection of the past, present and future. A postage stamp is a small piece of the epoch, captured in a modest picture on the paper.

At postage stamps, just like among people, there are their ordinary toilers and beautiful princesses. It happened so since the first miniature was born in 1840. The toilers, pasted on envelopes and packages, daily and hourly serve the people. They silently help carry the news and documents over cities and countries. They provide us with proper and regular communication and help in our affairs. Stamps-princesses are unusual and very rare. They have an interesting and sometimes incredible destiny. Such stamps are called legends, rarities, unicums. They are in a special account. They have their own names. They are known around the globe, regardless of where they have appeared. The life of such stamps is studied and described in books and articles. They are carefully stored in the world’s most famous collections.

Any collector-philatelist knows such names as the “Penny Black”, “British Guiana 1¢ magenta”, “Mauritius “Post Office”, “Treskilling Yellow”, “Inverted Swan”, “Twelve Penny Black”, “Sachsen 3 Pfennige red” and “Hawaiian Missionaries”… These postage stamps appeared in different countries at different times. But they all have an amazing story.

There are its own unique stamps in Russia too. A special place is occupied by Tiflis city post stamp of 1857.

Tiflis stamp (as it is already well established) was born on June 20, 1857. It happened six months earlier before the first nation-wide stamp of the Russian Empire appeared. Its birth was due to the serious reforms that took place in Russia and in the Transcaucasia. Therefore, the fate of the stamp, as well as the fate of the Caucasus region, has been complicated and even dramatic. It so happened that the history of two countries, Russia and Georgia, has intertwined in this stamp.

The birth of the stamp is connected with the names of many famous people of that time. Later Tiflis stamp has been undeservedly forgotten. It has been nearly lost in the vortex of revolutions and wars. Then it traveled over countries and continents. It is associated with unusual and sometimes detective and adventure events. And still it remained alive and survived to this day in several copies. And now the stamp of Tiflis city post with good reason takes its rightful place in the history of not only Russian and Georgian philately but also among the most outstanding exhibits of world postal services. It is among the ten rarest and most expensive stamps in the world. Many collectors of the planet dream about it.

This is what we have tried to tell you about in this book.

We have made an attempt to bring together the materials about Tiflis stamp published in different years. We have used the articles of such authors as K.K.Schmidt, S. Kuzovkin, N.I.Nosilov, B.A.Kaminsky, A.Vigilev, V.Pritula, A. Kolesnikov, G.Andrieshin, E.Sashenkov and others. The book brings together the documents of various years. In addition, there was added the information about people related to the fate of the stamp, an administrative reorganization of the Caucasus in the XIX century and the Heraldry of Georgia. These are the articles of O.Revo, G.M.Zapalsky, S.O.Mustafaeva, V.M.Mukhanova, V.Saprykova, T.Belousova, L.Tretyakova, K.Saksa and others.

Any outstanding world philatelic rarity usually has a name. For the first time in 1929 S. Kuzovkin called the stamp of Tiflis city post the Tiflis Unica. The name stuck, and then was often repeated in subsequent publications. Therefore, in Russia this stamp is often known by the name — Tiflis Unica. But now when the fifth copy of the stamp was found in the vault of the National Postal Museum at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC in the collection of G.H.Kestlin, it is not quite right to continue to call the stamp Unica. Therefore, in this book we will use the term — Tiflis stamp.

And so — this book is about the amazing object, legend and rarity. This book is about the stamp, which Russia and Georgia can be proud of. It is about the stamp, which has been in the most famous and prominent collections in the world. It is about the stamp, which is now estimated at millions of US dollars.

This book is about Tiflis stamp and unusual destinies of famous people, who at different times came into contact with it.

The author.

Chapter 1. Caucasian vicegerency

The administrative-territorial system

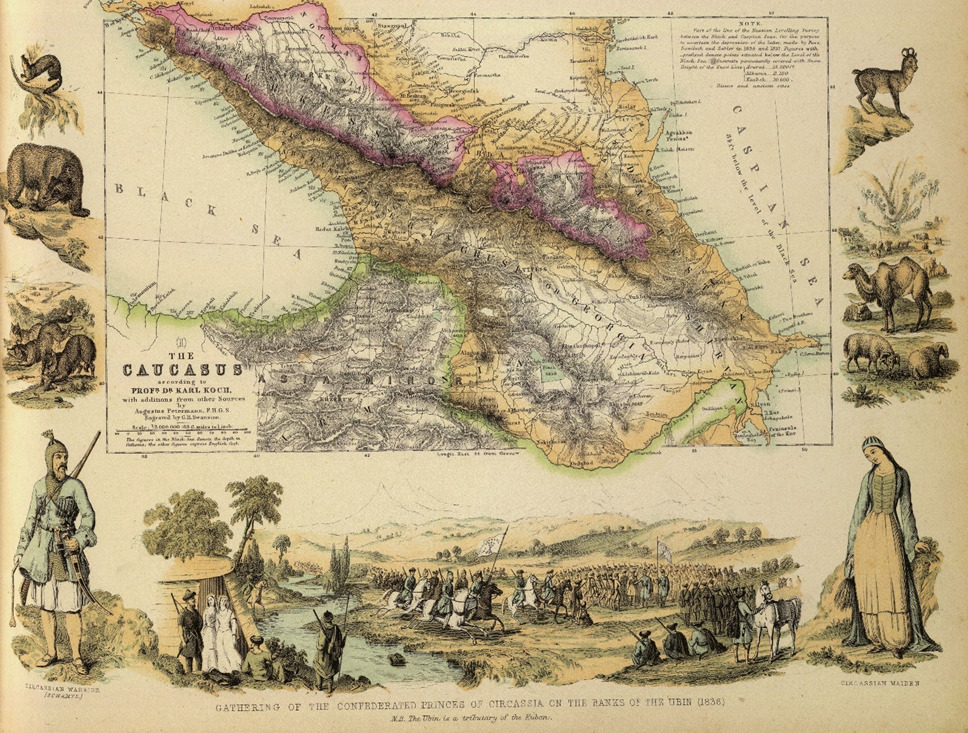

At the beginning of the nineteenth century in the South Caucasus the interests of the tree neighboring countries Persia (Iran), Russia and Turkey came into collision. The wars to possess these lands had been going on for a century and led to great changes in historical and political geography of the region. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the following lands existed in the South Caucasus:

— Khanates: Derbent, Baku Sheki, Shemakha, Talysh, Ganja, Karabakh, Nakhichevan, Erivan;

— Kingdom of Imereti;

— Principalities: Mingrelian, Abkhazian, Gurian;

— Akhaltsikhe pashalik and others.

Having conquered these territories, Russian government made a lot of administrative redistributions. The management of Caucasus was constantly changed in accordance with the Russian Empire management. The lands of khanates, sultanates and melikdoms were turned into administrative units, led by the military commandant from the Russian officers.

Failures in economic policy, as well as the national mutinies of 30s forced the tsarist government to make changes in its colonial policy. On January 1, 1841, under the new law commandant management system was liquidated in the Caucasus. Transcaucasian region (with the exception of Abkhazia, Mingrelia and Svaneti) is administratively divided into two parts: the western part called the Georgia-Imereti province and the eastern, which called the name of Caspian region.

In 1844, at the Caucasus territories, which entered in the Russian Empire (including Georgian province, Armenian region, the Caspian region) the Caucasian vicegerency was established with the center in Tiflis. It included one province and two regions:

— Georgian-Imereti province (Tiflis) — later transformed into the Tiflis province;

— Armenian region (Erivan) — was transformed into the Erivan province June 9, 1849.

— The Caspian region (Shamakhi) — was transformed into Derbent (Derbent) and Shemakha province in 1846. On May 30, 1860, Derbent Province was abolished and Dagestan region (Derbent) and Jaro-Belokan (Zakatala) District were established. Shamakhi province was renamed into Baku province on December 2, 1859.

After the establishment of the vicegerency at the vicegerent, the graph M.S.Vorontsov, another administrative reform of the region was performed. The project to reorganize the Region submitted by him was approved by the decree of the Russian Emperor on December 14, 1846. According to this law, all the South Caucasus was divided into four provinces: Kutaisi, Tiflis, Shamakhy and Derbent. In 1847, Derbent Province together with Tarkovsky and Shamkhalate Mehtulinsky Khanate formed a special administrative area called Caspian region. According to the document of 1855 Caspian region consisted of two parts: Derbent Province and the lands of Northern and Upland Dagestan. [1]

These administrative reforms aimed to strengthen the royal power in the Caucasus. In 1849 Erivan province was established. [2] Erivan province was formed from the parts of the Tiflis and Shamakhi provinces. The lands, lying on the southern slope of the Caucasus, from the Surami ridge to the Black Sea, were included into Kutaisi Governorate-General a few months after the end of the Crimean War (August 16, 1856). Apart from Kutaisi province such autonomous possessions as Abkhazia, Samurzakan, Tsebelda, Svanetia and Mingrelia were included in the Kutaisi governorate-general.

Caucasus vicegerency is a special body of administrative and territorial management in the Russian Empire. It was headed by the governor, who was appointed personally by the Russian emperor. The vicegerent reported only to the tsar and carried out full civil authority (other than the legislative). At the same time, he was a major military rank in the region. The Head of the vicegerency, the vicegerent of His Majesty in the Caucasus, possessed practically unlimited powers. He had the right to solve all the problems, which did not require publication of new laws.

He owned all rights to appoint the people, to displace and dismiss the officials and their responsibilities, to assign ranks, to reward, to grant their pensions (with the exception of officials of the State Control, the State Bank and the judiciary). Under the extreme circumstances, he could revoke the decision of the provincial and regional officials of the Caucasus region, that is, he supervised the governors, governors-general (both military and civilian). There was a consultative body at the vicegerent — the Board. It included two specially appointed by the Emperor individuals — representatives of the Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Home Affairs. In addition to them there were the Chief Executive on land management and agriculture, senior chairman of the Tiflis Court of Justice and the Director of the vicegerent’s Office on the Board.

Caucasian vicegerent, vested with extensive powers, was the representative of the supreme state power on the territories of the region and coordinated the activities of Russian ministries and departments, and partially performed the functions of the judiciary. [3]

It was this high status of the vicegerent that allowed establishing a separate issue of post stamps without the approval of this decision in the capital of the empire. The vicegerent was a competent deputy of Russian Emperor in the Caucasus and obeyed only to him.

The main legal documents determining the activity of the Caucasian vicegerent, were: “Highly approved the rules on the relationship of the Caucasian vicegerent dated January 6, 1846”, “Imperial rescript, issued to the name of Adjutant General Count Vorontsov “On strengthening the rights of the chief superintendent over the civil part of the Caucasus” from January 30, 1845” and “On introduction of all the cases of the Transcaucasian region and the Caucasian region into the Caucasian Committee” from July 23, 1845.” [4,5,6]

Only those officials, who enjoyed the full personal confidence of Russian emperor, could be appointed to the position of the vicegerent. Therefore, Tsar Nicholas I appointed the graph M.S.Vorontsov the vicegerent of the Caucasus and the Commander-in-chief of a separate Caucasian Corps by the decree of November 17, 1844. Novorossiysk and Bessarabian Governorate-Generals were under his command too. The rescript of the appointment said: “I consider it necessary to choose a performer of my indispensable will the person, who will get all my unlimited trust and who will combine renowned military prowess with the experience of civil cases, which are very important…”

The vicegerent was awarded the power and the authorities of the Minister in relation to all branches of management in the region. The cases which exceed ministerial authority were settled by him himself, reporting them to the emperor, or they were brought to the Office of the Transcaucasian Region Committee. The cases on the rewards of the officials and the reports were presented directly to the emperor. Vicegerent Vorontsov asked for the impact of the Ministers on the cases of the region to be discontinued. Just the influence of the Minister of Finance on the cases “of audit and control of any accountability” was recognized.

The power of the vicegerent on the territory entrusted to him was much more comprehensive than the governor-general’s. By the end of 1846 the control management was established. It included the Council and the Office of the vicegerent. The Council consisted of the officials and the governors appointed by the Emperor. He carried out the oversight functions over the entire management and the court in the Region. The vicegerent of the Caucasus supervised the chiefs of gendarmerie and railways. Military governors governed military institutions as well as the civil ones. The Headquarters of the vicegerent performed the general guidance. Later there appeared the Expedition of State Property on the Rights of the ministerial department.

By 1859, the Headquarters of the vicegerent consisted of the five original “ministerial departments”: the department of general affairs (which was in charge of the personnel, post offices, construction, healthcare and educational affairs), judicial, financial, state property and control department. There was even a special diplomatic Chancellery.

Since 1867 the vicegerent of the Caucasus was given even more extensive rights and powers, both in staffing the vicegerency and in managing the Region. Since that time Supreme supervision over the management of the Caucasus and the Transcaucasian region has been concentrated in the General Directorate established at the vicegerent, headed by a Chief. All the institutions included in it reported directly to him.

In 1883 governorate-general in the Caucasus was canceled and restored again February 26, 1905. It lasted until March 1917. [7]

Prince A. I. Baryatinsky — a vicegerent and a personality

In 1856, the vicegerent of the Caucasus was appointed Prince Aleksander Ivanovich Baryatinsky. He continued and developed the reforms, begun by his predecessor graph Mikhail Vorontsov. Large-scale reforms of the postal service in the Caucasus and the release of the Tiflis stamp are associated with a name of Baryatinsky. The personality of the Vicegerent-Prince had special significance for these transformations.

It was an amazing man. Historically, he had very close relations with the Emperor Alexander II. Partly due to this relationship Baryatinsky could introduce his reforms and innovations in the Caucasus. A special place of the count at the imperial court, and his unusual nature allows you to answer the question — why the first stamp on the territory of the Russian empire appeared in Tiflis. He was an extraordinary man, capable not only of military deeds, but also of determined actions in relation to the royal power itself.

Prince Alexander Baryatinsky was of noble-birth, Riurikid in the fifteenth generation. He was born and grew up in an atmosphere of unprecedented luxury. Only very few people in Russia owned the fortune, which his father bequeathed to him. His father, Prince Ivan Baryatinsky, died when Alexander was 10 years old. At age 14, his mother — Maria Baryatinsky, took the teenager with her second son Vladimir to Moscow to “master the sciences.” But two years later, Alexander desired to join the military.

In June 1831, he moved to St. Petersburg, and he was admitted to the school of guard sergeants and cavalry cadets with further enrollment to the Chevalier Guards. There he immediately showed indiscipline and restlessness. The result was the “weak success in the sciences.” Negligence in the studies passed into negligence in the service. The disciplinary regiment book had many entries about his penalties for “the pranks” of all kinds. As a result, the young Alexander Baryatinsky got his fame as a reveller, a playboy, a participant of binge-drinking parties and scandals. His mother generously provided her son with financial help. But this money was often not enough to pay his gambling debts. Once a future famous Russian poet Alexander Pushkin and his friend Sergei Sobolewsky helped Baryatinsky to get out of such debt.

Tsar Nicholas I had heard about the unauthorized behavior of the young Prince, about his amorous adventures. Moreover, it became known about a love affair of Prince Alexander Baryatinsky with the emperor’s daughter — Grand Princess Olga Nikolaevna. Nicholas I was personally convinced that the relationship between them went beyond it was permitted. So, he sent the young Prince Baryatinsky away to the Caucasus.

In the spring of 1835 20-year-old Alexander Baryatinsky holding the rank of cornet of the Imperial Guard Cuirassier Tsarevitch Regiment, arrived in the area of military operations. There was a different life there. There was a war in the Caucasus, and it was impossible to hide behind the noble family or great wealth. Baryatinsky had to quickly forget about the capital pampering and idle talk. It was with youthful courage that Prince threw himself into the hottest battles. During the clashes with the mountaineers, he repeatedly received perforating gunshot wounds. His comrades-in-arms used to say that “Prince Baryatinsky’s belly was like a sieve.” His courage, endurance, and the ability to endure pain amazed a lot of people.

After he had received a heavy rifle bullet wound in his right side, Baryatinsky returned to St. Petersburg. He came to the capital from the Caucasus holding the rank of lieutenant; he was awarded by the honorary for the Russian Officers Golden Arms “for Bravery”. In 1836, after he had received the course of treatment, he was appointed to stay at His Majesty Successor Tsarevitch. Three years spent by him traveling with the heir over Western Europe, made them very close and initiated their long-lasting friendship with the future emperor Alexander II.

In March 1845, Alexander Baryatinsky, the owner of the magnificent estate of Marino and huge ancestral treasures, a handsome hero of the Caucasian War, who became the adjutant of His Imperial Highness in 1839, left the capital and came back to the Caucasus. That time he had the rank of colonel.

In February 1847 he was appointed the commander of the same Kabardinsky regiment, where he felt very much at home due to the years he spent there fighting at war. There he was promoted to the rank of Fugel-adjutant, and in June 1848, when Prince displayed his courage and bravery at the Battle of Gergebil, he became a Major-General with enrollment in the retinue of His Imperial Majesty. At the same time, the Emperor Nicholas I unexpectedly decided to “load young Prince with favors”. The tsar had personally chosen him a bride from the Stolypin’s family and thought of a plan to marry them. According to Nicholas I, it was hard to find a better husband for the maid of honor. In this case a fabulous wealth of the Prince was of great importance.

But the marriage was not in the plans of Alexander Baryatinsky. For a while, he managed to evade the will of the emperor. But when the tsar’s wrath became extremely strong, the Prince made a step quite incredible for that time. Being the elder son, he was supposed to inherit the wealth from his father which he refused in favor of his younger brother. So, in an instant the richest man in Russia had turned into an ordinary soldier, living on the state salary. Nobody was happy with the poor bridegroom — neither Nicholas I, not the bride. The wedding was canceled. The Prince, himself was inwardly proud of his deed, and in a moment of candor once told a friend: “I have not succumbed to the emperor himself. And what an emperor!…”

However, it was only after the death of Nicholas I that the young Prince managed to become the first person in the Caucasus. The throne was occupied by his son Alexander II. The new emperor did not see “for the role of the Russian proconsul in the East” a more suitable person, except Baryatinsky. Therefore, in the summer of 1856 Baryatinsky was appointed the commander of the Separate Caucasian Corps, and from 1 July 1856 “performing the duties of Vicegerent”. In the August of the same year, he became the vicegerent of the Caucasus with further promotion into a general from infantry.

From this moment the deep reforms developed in the Caucasus. They could be put into life only by such a brave and educated man like Prince Alexander Baryatinsky. The powers of the vicegerent and personal friendship with the Emperor of Russia allowed him to carry out any initiative, regardless of the Government officials. In addition to it there were legendary military deeds of the Prince. Having totally conquered the Caucasus and captured the main enemy in the Caucasian War Imam Shamil, Baryatinsky became a field marshal at the age of 44. It was the highest military rank he could get. But the adventures of the Prince did not end there.

There happened an unexpected thing. 45-year-old field marshal and the vicegerent of the Caucasus passionately fell in love! He loved so strongly and passionately, as it could happen only in adolescence. But he had to pay a fortune for his feeling. Not to marry one woman, he had to refuse the wealth and on the contrary to marry another one — he had to leave the post of vicegerent of the Caucasus. In May 1860 Prince Alexander departed from the Caucasus to a long vacation abroad due to his “ruined health.” This wording concealed the dramatic events of his personal life. That was a love affair!

Baryatinsky had developed a romantic relationship with the wife of one of his staff officers — Lieutenant Colonel Davydov. This young woman was the daughter of the well-known all over Tiflis Princess Mary Orbelyani. Georgian women have always conquered many men by their beauty. They attracted not only the field marshal, but even the emperor himself. The Prince had known that woman when she was a child and continued to call her just Lisa. He behaved with her like an old relative or a guardian of a little child. Baryatinsky used to tell everyone that he was taking care of her education and development of the mind, that they were reading serious books. They spent the whole evenings together. These strange pedagogical exercises were known throughout the city. A lot of rumors were spread about them.

The husband of the Princess, a man of a very limited mind, enjoyed the Field Marshal’s favor and hoped to get a place of quartermaster-general. Temporarily he was even appointed to this position. But this test revealed his weakness. When the hope to make a career was ruined, there happened a public scandal between the husband and the wife. Princess Mary ran away and disappeared into nowhere. Irritated husband became the laughingstock of the whole town. He was furious and threatened to go to St.Petersburg to seek justice. But he ended up resigning and fleeing abroad. At that time his wife and the field marshal himself were also abroad. [8]

The vicegerent, like a mountaineer kidnapped and hid his beloved Georgian princess in the place, where nobody could take her away from him according to strict Russian laws. This is what was meant by “treatment abroad”. This escape with the mistress did not suppose a quick return. The career cross was finished. Baryatinsky resigned but received it only in 1862. Outraged husband came abroad to demand satisfaction. The field marshal fought a duel for the sake of the love of the beautiful Georgian woman. For a long time that duel blocked the opportunity for Baryatinsky to return to Russia, which he badly missed.

They had lived together with Elizaveta Dmitrievna, nee Princess Orbeliani Dzhambakur-Orbeliani for almost 20 years. The Prince died in Geneva, but his will was to be buried in Kursk province, in the ancestral village of Ivanovo, which was fulfilled. [9]

As we can see, the biography of this remarkable man, his temperament and nature not only allowed him to win on the battlefield and resolutely implement the reforms, most daring for that time (including those in the postal service), but also to undertake the steps in his personal life, which none of his contemporaries would dare!

Prince A.I. Baryatinsky — a vicegerent and a reformer

Let’s go back to the state activity of the Prince, his role in the system of imperial power of that time. Personal correspondence of A. I. Baryatinsky and Emperor Alexander II provides a lot of information for understanding the reforms carried out at the time in the Caucasus. The letters of the considered period were included in the personal archive of Field Marshal, which after his death was handed to A.L.Zisserman, who wrote a large book on the life and work of Baryatinsky. [10]

After the revolution, the fate of the letters remained unknown. In 1966, an American researcher Alfred Rieber published a book, “The politics of autocracy”. The second part of the book is the above-mentioned letter, published retaining all the original features, including the French language. In his publication Rieber refers to the Archive of Russian and East European history and culture at Columbia University. [11]

The letters tell an interesting information about the relationship of Alexander II with Baryatinsky and are the source of information on the history of Russia’s foreign and domestic policies in the 1850—1860 and, above all, on the final stage of the Caucasian War.

Since the emperor and the vicegerent were close friends, their correspondence is personal in nature. This is evident by the way Alexander II refers to the Prince (“dear friend,” “my dear Baryatinsky”) as he passes the best wishes from his spouse and from the Empress Dowager (she died in 1860). When writing a letter in French the emperor addresses his interlocutor using polite “you”, but in Russian phrases he turns to friendly “you”.

The financial situation in the country was very difficult after the Crimean War. Alexander II constantly reminded his vicegerent about it, demanding a “wise economy” of funds and curtailment of expenses. Baryatinsky tried to do his best to fulfill this instruction of the monarch not only in military affairs but in the civilian affairs while ruling the region. Carrying out further reforms in the field of postal services he, as a vicegerent, set up a task in front of the management of the post office — to sort out the mess and to save the costs.

The monarch approved the project of the military reforms and repeatedly reminded of the need to accelerate work on the drafting the civil part of the management restructuring, which included mail service.

Being an outstanding military commander and a great statesman, A. Baryatinsky understood that the development of communication was of great importance for the Caucasus region. Mail at that time was the only means of communication, and therefore its proper organization was a prerequisite of all planned and ongoing reforms. Without clearly-established postal service no successful military operations of the army as well as any civil transformation in the economy and social life were possible. Therefore, the vicegerent could not ignore the issues of reorganization of the post service in the Caucasus.

As it can be seen from the correspondence of Prince Baryatinsky and Emperor Alexander II, the vicegerent of the Caucasus had the most extensive powers granted to him by the law, and he had practically unlimited power of the tsar deputy in the region. Taking any decision on reorganization on the territory, trusted to hi, the vicegerent could always be sure of the support of the emperor, which was repeatedly used to solve serious financial and political issues. The Emperor used to write to him: “You decide yourself on the spot…” [12]

As soon as he was appointed a vicegerent, A.I.Baryatinsky had immediately taken the first steps to provide his full independence. On August 8, 1856, he filed a memorandum to Alexander II in which he asked to withdraw all the incomes and expenses on the Caucasus region from under the authority of the Ministry of Finance and give the vicegerent a complete freedom over them, as it was until 1840. Thus, in 16 days after his appointment the vicegerent of the Caucasus, Alexander Baryatinsky got free of the Minister’s of Finance patronage.

On April 25, 1857, the decree that regulated relations between the vicegerent of the Caucasus and the Senate was issued. Prince Baryatinsky received the right to suspend the execution of the decrees of the Senate in judicial, civil or criminal affairs in case of “local inconvenience, trouble or harm” for the Caucasus region. When the cases referring to the Caucasus came to the Senate, the Senate was deprived of the possibility to send them to the Ministry for consideration and could refer only to the vicegerent.

At the General Directorate of the vicegerent, Prince Baryatinsky established a Temporary department, where all the cases requiring new legislative measures on the issues pertaining to the different sections of the management and the development of well-being in the region were concentrated, and which was in charge of preparation and development of various projects. This department was also involved in the collection of “detailed and correct information about the status of the region, the progress made in the cases, the costs and other issues connecting with the administrative statistics of the vicariate.”

Vicar was given the highest supervision over the execution of laws by local institutions. All the offices and officials as well as individuals located in the Caucasus had to report to him. The vicegerent was the chief administrator of credits.

According to the law, the vicegerent had the right to expel any person from the region if such residence was recognized harmful. But they were not only individuals, who were expelled. After the victory over the mountaineers in the Caucasian war, the whole nations were expelled. The vicegerent was charged with supreme supervision of the Muslim clergy and the spiritual establishment. [13]

Expanding his reform efforts in the Caucasus Prince A.Baryatinsky immediately drew attention to the improvement of postal services in the region. A postal service at the time urgently demanded its radical change.

Chapter 2. Tiflis mail of the ХIХ century

Postal Service of the Caucasus in the second half of the nineteenth century

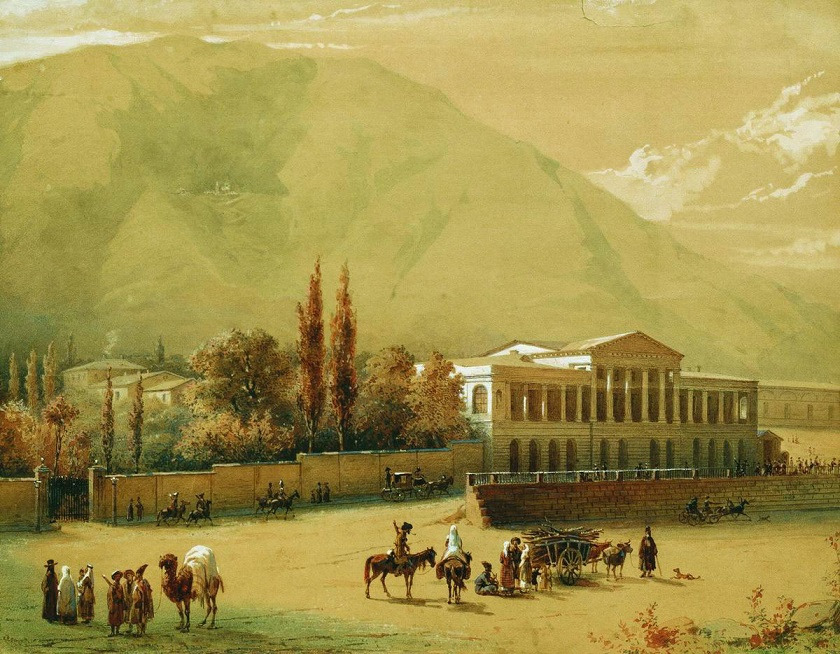

After the accession of Georgia to Russia in the first place it was scheduled to continue the construction of post tract from Mozdok to Tiflis with the length of 258 versts with the construction of ten stations to serve the postal rush on it and one post office in Tiflis. But those plans were hold back by the scarcity of funds allocated.

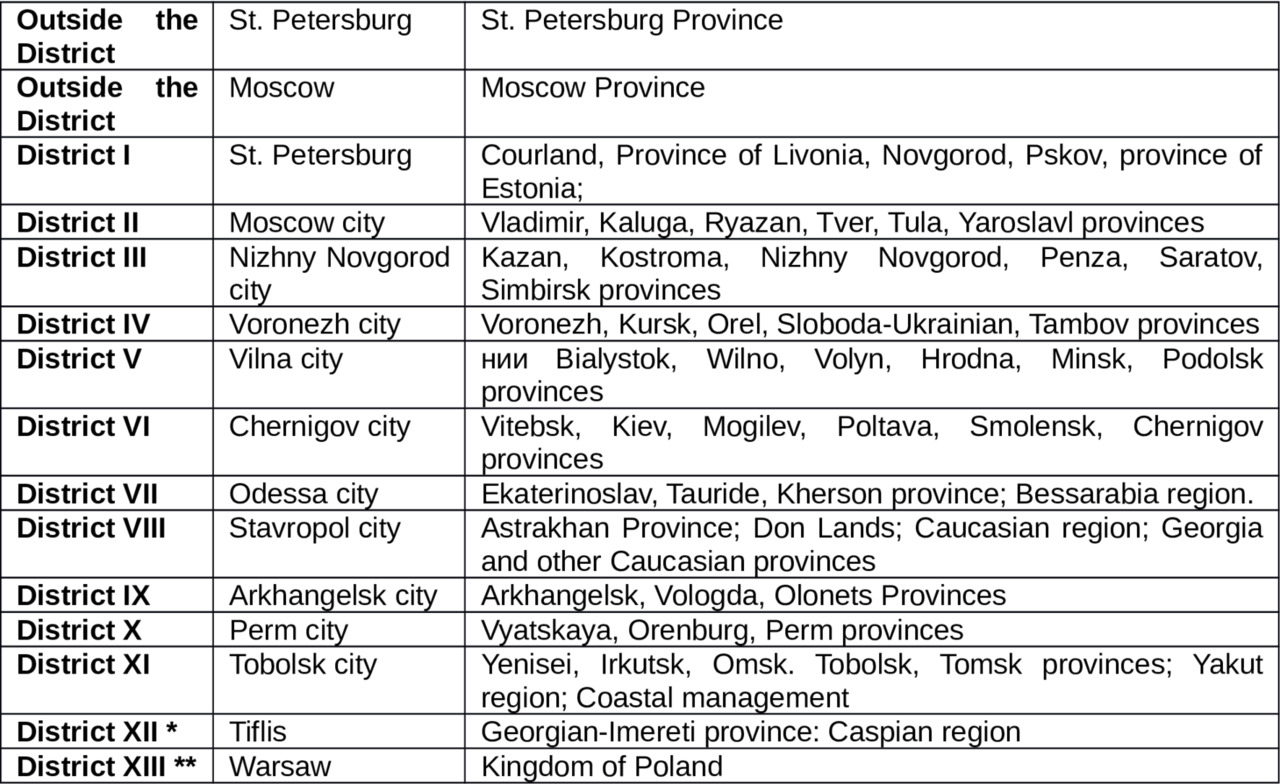

In 1830, to simplify and accelerate the movement of office correspondence, the Post Agency reorganized the Russian post offices. By the nominative Decree of Tsar Nicholas I to the Senate “On the new structure of the mail system” from October 22, 1830, the division of the territory of Russia into 11 postal districts was provided. (See. Table 1).

Five provincial post offices were canceled, and provincial, regional, border and foreign post offices had to report directly to the Postal Department. Georgia postal institutions were included in the postal district VIII.

The city of Stavropol was determined to be the seat of Postal Inspector of the district; one of his assistants had to reside in Tiflis to supervise the post offices of the Transcaucasian region. Tiflis post office was elevated to the rank of regional office with a staff of 12 people (4 sorters were added). The new “Regulation on the system of the postal unit” was put into operation since January 1, 1831.

Further reorganization of Tiflis post office is associated with the general changes made by the tsarist government in 1840 for civilian control of the Transcaucasian region. According to the nominative decree to the Senate on April 10, 1840, the provinces lying between the Black and Caspian seas were to form Georgian-Imereti province and the Caspian region. Tiflis was determined to be the main city of Georgia-Imereti, and Shamakhi of the Caspian region. This decree came into force since January 1841. It is mentioned in the first chapter of this book.

By that time, the post offices had been established:

the regional one in Tiflis;

the county ones of the first class — in Baku, Erivan, Nakhichevan, Kutaisi and Redoubt-Calais;

second class — in Gori, Dushet, Ananuri, Telavi, Sngnahe, Yelizavetpol, Cuba, Derbent and Vladikavkaz.

County post offices were to report to the regional office of Tiflis. Further, with the abolition of earlier existing establishments in Georgia and the development of administrative management in the conquered areas of the region (which coincided with the intensification of military operations in the Black Sea and on the Caucasus line) — it is natural that the role and the importance of postal services in the South Caucasus should strengthen.

By the middle of forties there were operating the following types of postal service in Georgia and Tiflis:

1) Extra-mail, with which the correspondence was sent to the center on a regular basis, twice a week, according to a strictly determined route (St. Petersburg, Moscow, Novgorod, Tver, Tula, Voronezh provinces, the Land of the Don Cossack Host, Nizhny Novgorod, Odessa and Warsaw Provinces)

2) Heavy-mail — also to the center twice a week, with the division of correspondence to other places of the empire.

3) Easy-mail — to the postal places of the Caucasus and adjacent provinces.

4) Fly-mail — to border garrisons.

5) Relay mail — abroad, Vladikavkaz, according to a special work sheet with the payment of money for postal services.

There didn’t exist any telegraph lines at that time. The first telegraph line was opened in the Caucasus between Tiflis and Poti in 1860.

The formation of new province and region in the Transcaucasian region made Postal Department change the division of Russian into postal districts. In December 1840 taking into account the peculiarities of the region, it was decided to establish a new postal district for Georgian-Imereti province and for the Caspian region. [14] All post offices of Georgian-Imereti province and the Caspian region were transferred to the newly formed Mail District XII. Tiflis was identified to be the residence of the Postal inspector of a new district, and for his assistant — Shamakhi. The Cossacks were exempted from their obligation to accompany the mail in the Caucasus. They were replaced by postmen. The responsibilities of Tiflis post office had increased. With the addition of 10 postmen to accompany the mail its staff became 22 people. Tiflis regional post office in 1841 became known as provincial one. However, the order implemented in 1840 for civilian management of the Transcaucasian region, turned out to be in many ways uncomfortable.

In 1842, when inspecting the region, it was found out that due to its remoteness and the specific local conditions, the Ministry failed to establish there a proper supervision over the introduction of a new civil management. In addition, the intervention of the Ministries in the affairs of the Transcaucasian region often weakened the authority of the local manager. The Special Committee of the Caucasus established by the decree to the Senate of April 24, 1840, was only interested in the general direction of civil affairs in the region and failed to exercise proper supervision over the activities of new institutions in the Caucasus. According to the Minister of War Knyazh A.I.Chernyshev responsible for the general management of the affairs of the Transcaucasian region, to address the difficulties encountered, it was necessary to establish a special institution in St. Petersburg, which could keep all cases on civil management in Transcaucasia, having withdrawn them from Ministry, “until all the sections will get the complete control”, that was what he wrote to the Emperor Nicholas I on August 19, 1842. [15]

A temporary department was organized according to the Decree to the Senate on August 30, 1842. At the same time Caucasian Committee was also completely reorganized. In connection with this the reorganization of the main department of the Transcaucasian region located in Tbilisi also took place. On November 12, 1842, Tsar Nicholas I approved “Mandate to the General Directorate of the Transcaucasian region”, which determined the main goal: to rapidly establish “strong civil accomplishment” in the South Caucasus This “Mandate” raised the authorities of the Chief Commander of the region up to ministerial authority, acting in place. The Ministry could apply to the institutions reporting to them which were located in the South Caucasus only through the Chief Commander. Chief Directorate of the Council composition was limited to five members: three soldiers and two civilians. Military members of the Council in addition to their common duties were obliged to supervise departmental agencies which were out of local supervision: one was made responsible for training, the other supervised the customs and the third one took care of mail. In this regard, the positions of corresponding supervisors were abolished, including the position of postal Inspector of XII postal district.

The first member of the Main Directorate of the Transcaucasus region, who at the same time was managing mail department, was a lieutenant general and well-known Georgian poet Knyazh Alexander Chavchavadze, who came to this post on December 28, 1842. [16]

Thus, in 1840 the Transcaucasian region post offices were transferred from the direct control of the Postal Department of the Empire under the jurisdiction of the Chief Executive of the Transcaucasian region. The law of 1840 stated: “… the agencies, which are subject to special control, such as customs, educational and mail agencies, are under dependence and supervision of the Chief Executive of the Transcaucasian region which relating these agencies operates on the basis of regulations and rules, in particular for each of these existing agencies.” [17]

The final withdrawal of the twelfth postal district from under the control of Postal Department and all the functions to manage all the Agencies were transferred to the main authorities of the Transcaucasian region at the vicegerent graph M.S.Vorontsov.

In January 1845, when M. Vorontsov was appointed the vicegerent of the Caucasus, his authorities were determined by a special rescript of Nicholas I: “having laid on you, along with the title of Commander-in-chief of the troops in the Caucasus, the main command of the civil part in the region, as my vicegerent and consider it necessary, for the good of the service, to strengthen the authorities, which until now have been given to the chief superintendent of civil section, I, in my full confidence to you, command: all the cases, which according to currently existing order have to be submitted on behalf of the Chief Directorate of the Transcaucasia region to the Ministry to be solved, should be solved in place. Moreover, you are provided with an authority, when you find it necessary, to take all the measures required by the circumstances, in place, reporting to me directly all your actions, as well as the reasons these actions were caused by” [18] With this document the power of Knyazh Vorontsov was extended to the Caucasian region (later renamed in the Stavropol province by the decree to the Senate on May 2, 1847).

The vicegerent of the Caucasian region, Mikhail Vorontsov was a good administrator and a talented Russian official. He was born and brought up in England, where he received an excellent education. When he was the Head of the region postal roads were being laid and the bridges were being built. At the same time Tbilisi became a large administrative center, the city’s population increased, there appeared is a large number of beautiful new public and private buildings. All of this strongly demanded to improve postal service.

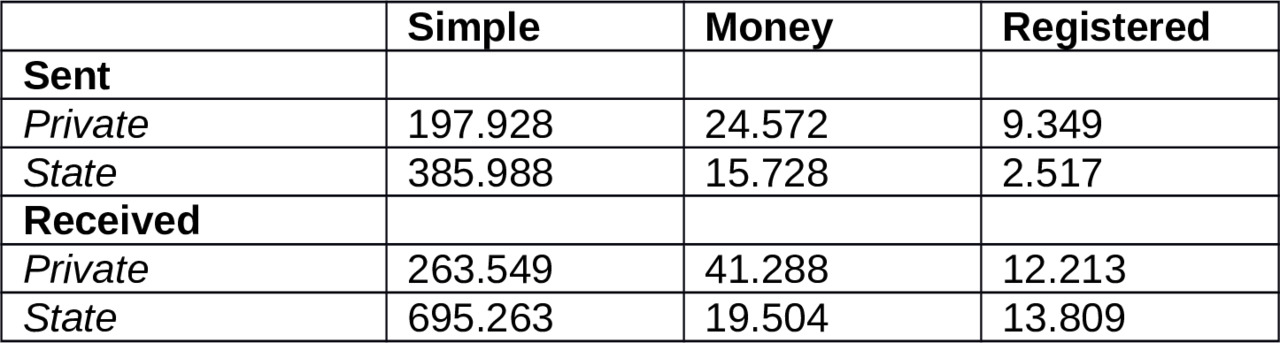

Table 2 illustrates the movement of mail only for the city of Tiflis in 1855. It shows the development of the cultural needs of the population of the Caucasian capital, which was primarily military and bureaucratic, in terms of coverage the city with postal services.

Interesting statistics of the XIX century: in the late 50s for 100 inhabitants of the cities of the former Russian Empire there were 12,3 sent and received messages a year; for 100 inhabitants of the city of Tiflis there were 36 sent and received messages and in England for 100 inhabitants there were 300 messages. [20]

A cardinal measure, which contributed to the development of postal services, was the fact that postal stations of Tiflis province and the city of Tiflis had been withdrawn from the jurisdiction of the County Police and transferred as an experiment under the management of the postal authorities of the Caucasus for three years. This governmental action took place on October 26, 1857. [21]

The regional administration tried hard to facilitate the use of public postal services for the population. For example, there were declared opening and closure hours of post offices in the postal regulations of that time. But from “travelling persons, those who were not constantly living in the cities, such as neighboring landowners, farmers and roundabout residents” — letters were accepted at any inopportune time. [22]

I.I.Nazarov, appointed the member of Chief Management Board of the Trans-Caucasian Region and Manager of the postal department on January 1847, began to be called “Manager of postal department of the Caucasus and beyond the Caucasus.” In this position he replaced the Knyazh A.G.Chavchavadze. [23]

However, the authority given the to the vicegerent M. Vorontsov by the Tsar, had been fully used by him only in 1848 in the process of reforms carried out in the post office of Tiflis province.

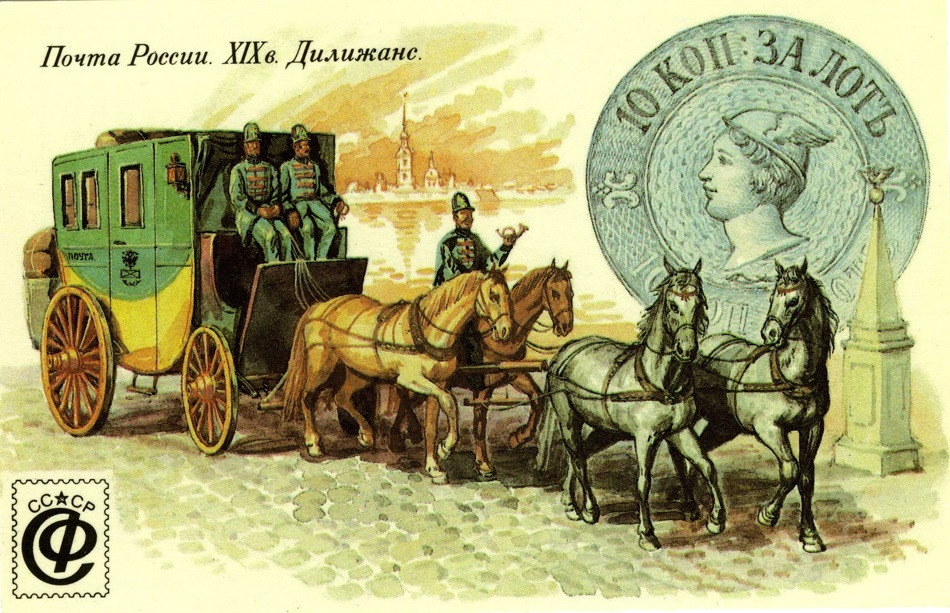

Since the 70s of the XVIII century in Russia there formed a system of postal services and transportation of the passengers by “mail”, which was almost unchanged until the middle of XIX century. Postal relays (stations), arranged at the expense of the state, were given to the individuals to be maintained. They had to have 25 horses, 10 wagons on wheels or sled at every station, as well as all the equipment necessary for postmen and mail transportation (horse harness, suitcases, bags, saddles, uniforms of postmen). A stationmaster was also responsible for hiring postmen. Even the serfs, released on the rent by the landlord, were allowed to be hired for this tedious service. The revenues of the postal station keeper consisted of the statutory fee (12 kopecks per 10 verst’s), proceeds from the sale of food and alcoholic beverages at the post office, from the placement of travelers for the night. Everything, which concerned the work of the post office, subjected to strict state regulation.

In winter and in summer the couriers were to be driven with a speed of 12 versts an hour, and in autumn and spring — 11 verst’s an hour. Other travelers were ordered to be driven more slowly: in winter and summer — 10 v/h, and in the spring and autumn — 8 verst’s an hour. Everyone who enjoyed the services of the post office, as well as all the correspondence was recorded in a special logbook.

In the reign of Emperor Nicholas I, vigorous measures had been taken to put in order earlier considerably neglected system of postal communications and postal stations. In 1837 he visited the Caucasus and signed a decree on the construction of mail houses every 3—4 postal stations on the Caucasian tracts. Along with the intensification of the movement of postal crews, the government of Nicholas I sought to establish a permanent staff of postal employees and station keepers. On these purposes the lease period of postal stations was increased from 3 to 12 years, and the rental amount was to be determined not at the auction, but according to official estimates fixed for each post office. In Nicolas’s list of activities to improve the situation in the Russian Empire there was the item of constructing on the main road’s postal stations uniform in appearance and convenient for travelers.

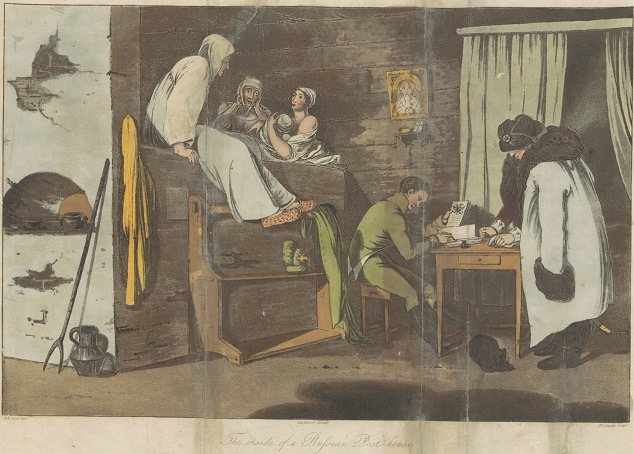

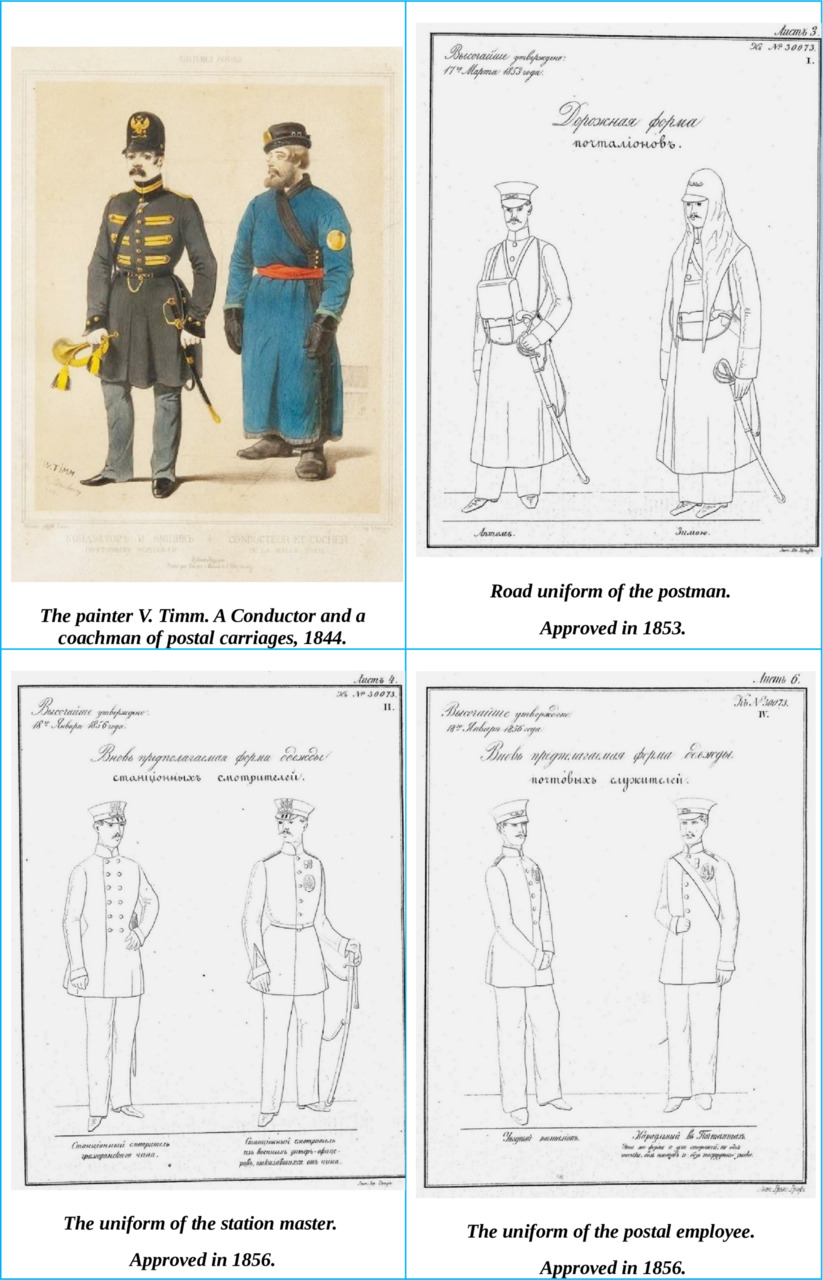

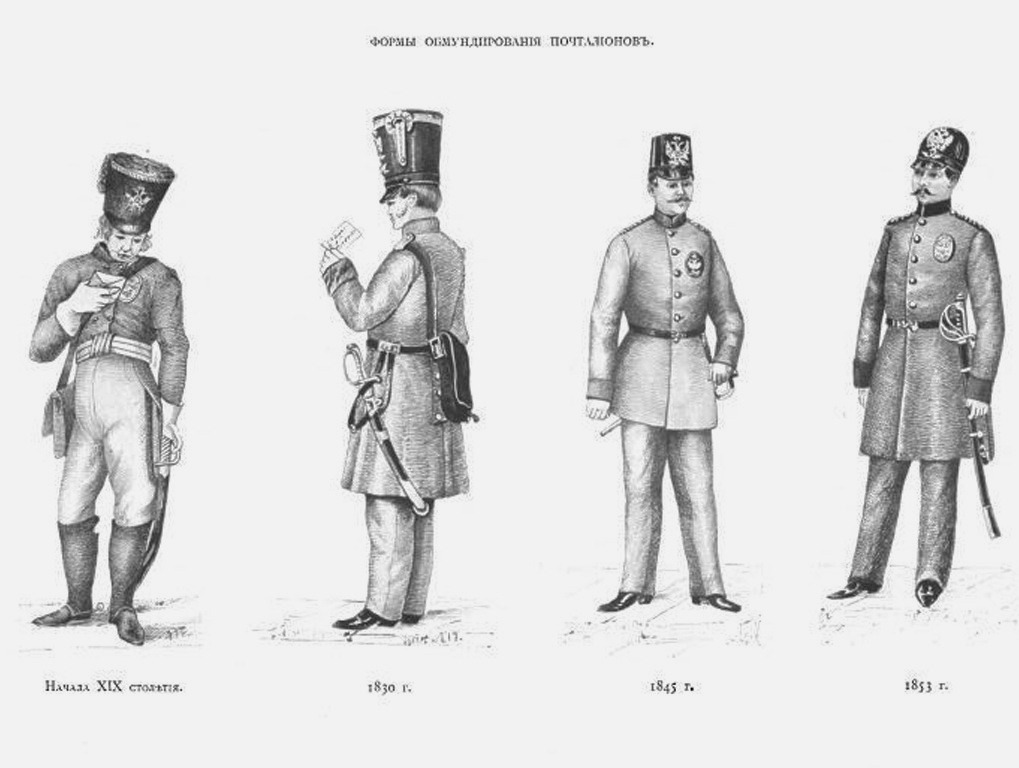

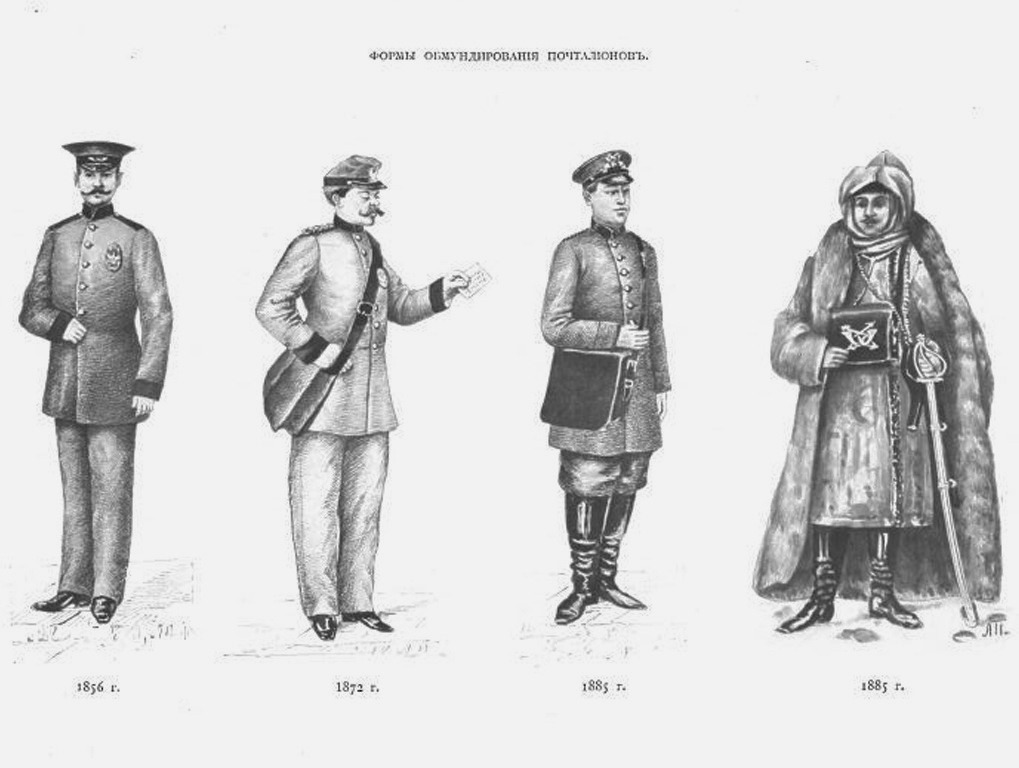

A new sample of postal uniform for the postmen was introduced in the 40s: red cloth caftan with a white belt. It is worn over the ordinary dress. Peaked caps were also red. A postman wore on his chest a brass badge with the state national emblem and a strap with the horn over the shoulder. Special uniforms existed for mail conductors and coachmen. Later, in the years 1856—1857 the mail uniform was changed.

An interesting analysis of the postal service was done by B.A.Kaminsky, who described a postal rush in the Caucasus. He gives a more complete understanding of the need to reform the postal service, and a haste to issue a stamp of Tiflis city post office. [24]

In 1831, for the first time several postal stations were sold under the responsibility of the individuals — postal landlords. At the same time the question was raised about the management of the postal rush in the region on the same basis as in the internal provinces of Russia, and also it was mentioned that the supervision over the stations, which before was the responsibility of the heads of military guards, should be transferred to the Post Authority. At the end of 1833 there were already 90 postal stations in the region. But at these stations there were no station houses yet, and postal landlords were placed together with the Cossack posts in the huts or even in mud huts.

Georgia started to construct the station houses in the years 1834—1835. These houses were considered to be connected to military posts. By the nominal decree of 13 July 1830 to the sum of 80,000 rubles in silver, assigned to build these houses, a new sum of 50,000 was added.

The construction of all postal stations in Georgia ended in 1837, and the postal rush could switch completely from the Cossacks to the postal landlords. This fact made it possible to temporarily take the stations of the Transcaucasia region in the Post Office and appoint station masters for them. To reduce the costs, it was planned to have one station master for two stations — every other station.

A special situation, in which the postal rush was in the region, was finally legalized by the decree to the Senate on April 10, 1840. In the decree “The institution for the management of the Transcaucasian region” the supervision over postal rush and improved maintenance of postal stations was entrusted to the district managers through the rural police.

“The provision on the postal station management” was approved on November 18, 1842. It provided the transfer of all the stations in Russia from under the supervision of the police to under the management of the Post Authorities. But the postal stations in the Transcaucasian region remained in the same affiliation. [25]

The new system of transfer of the stations under private maintenance (bidding) introduced in the early 30-ies, received a greater spread since 1841, because the Cossacks were released of the obligation to accompany the mail.

In Russia, the stations at the auction were taken under supervision by wealthy people who knew the station business and who were able to endure any difficulties — even a poor harvest of forages, mortality of horses. In the Caucasus, on the contrary, to “the trading” poor people came, among whom there usually were the merchants, who were ruined in trade, contractors who failed to find job, retired officials and other small entrepreneurs unfamiliar with the peculiarities of postal rush and with the station economy.

Naturally, these postal landlords would only like to improve their own financial affairs. Therefore, having received the money in advance from the provincial authorities, they spent it on their own needs rather than buying the necessary property for the stations. Lack of unity of authority to oversee the accomplishment of the stations gave them ample opportunities to deviate from improving the postal service or from just maintaining the stations in good condition.

As a result of such activity the stations on the roads of Transcaucasian region fell into disrepair. Inept owners were removed from the supervision of stations, often without waiting for the expiry of the three-year period provided for by the contract. And again, the stations were sold to another postal landlord. It happened that during a three-year contract the stations were supervised by several postal landlords in turns.

In the report to the vicegerent of the Caucasus on May 15 1855, the councilor of the Chief Directorate of the Transcaucasia region F.E.Kotseb describes the drawbacks of the system to lease the stations from “the auction” in the Tiflis province: “for a long time the mail from Tiflis was sent by the bulls, for want of horses.” [26] There were also frequent cases when the travelers, who had been waiting for post-horses at the station for several days, had to go on foot along mountain roads.

Postal officials in the South Caucasus took no part in all this, except that they “monitored the progress of the mail”, because, as F.E.Kotseb stated in his report “rural police, no doubt, has more means to sustained supervision over serviceability of the stations than a post office with its limited staff.” The activity of the postal district manager was limited to correspondence with the governors about the station’s faults noticed when visited by traveling postal officials.

Seeing the catastrophic consequences in the postal rush and station economy of some provinces of the Transcaucasian region, which was the result of selling them from the “auction”, Transcaucasia postal authorities repeatedly appealed to the vicegerent with a proposal to introduce other system of “evaluation” that existed then in all the other provinces of Russia and according to which the stations should have been given under supervision to reliable postal landlords for a long term — 12 years. The same recommendations in March 1848 were expressed to the vicegerent and Commander-in-chief of the Postal Department.

However, M.S.Vorontsov rejected these proposals, giving the governors only the instructions to take measures to improve the maintenance of the postal stations. But that hadn’t led to noticeable improvements of the stations. On the contrary, the amount of charges for maintenance had increased. For example, in 1848 it amounted to 277 321 rubles, but in 1856 it had already reached 378 525 rubles.

When appointed the vicegerent of the Caucasus, Prince A.Baryatinsky at the beginning of 1857 paid attention to the huge amount of the rural levy allocated annually for the maintenance of postal rush in the province. He decided to eliminate all that chaos. On January 30, 1857, he appealed to the Caucasian Committee with a proposal to transfer, as an experiment, the stations of Tiflis province, which were in the worst condition as compared to other provinces, from the jurisdiction of the County Police under the management of the Post Office for three years. [27] The proposal was considered in the Caucasian Committee and approved on June 7, 1857, by the Tsar Alexander II. [28] But to introduce it in the “Complete List of Laws of the Russian Empire,” this decision was communicated to the chairman of the Caucasian Committee of the Minister of Justice, only on October 26 of the same year. S. Kuzovkin in the article “The Forgotten Philatelic Unica”, published in №1—3 magazine “Soviet collector” for the year 1929, mistook the date of the original to determine the arrival time of Tiflis stamps in the postal circulation. [29]

Nikolai Semenovich Kakhanov was appointed to be the performer of the decisions on reorganizations of the Post Office. He was a hereditary nobleman, a son of the councilor of the Main Directorate of the Transcaucasian region, Georgian civil governor Semyon Vasilyevich Kakhanov. In future, Nikolai Kakhanov rose to the rank of Lieutenant General. His daughter married into the family of Baryatinsky marrying Prince Victor Victorovich Baryatinsky.

On behalf of the vicegerent of the Caucasus, N.S.Kakhanov had to investigate the reasons of the poor state of the stations, as well as to find ways to reduce money for their maintenance. (Previously, describing the correspondence of Knyazh A. Baryatinsky with the emperor, we have noted that Alexander II especially emphasized the necessity of a serious economy of state expenditures in the Caucasus.) In addition, the vicegerent expressed to N.S.Kakhanov his wish to establish the movement of mail coaches in Transcaucasia if only using the main tracts.

About a year later N.S.Kakhanov provided the vicegerent with a report, in which he outlined the project of reorganization of postal rush in the Transcaucasian region. [30] Outlining the reasons for the increase cost of maintaining the stations, on the basis of the collected information and produced calculations, he argued that the amount of money coming from rural levy was enough. At reasonable and conscientious activities of the postal landlords it was possible even to get the remainder and savings.

However, he considered his assumptions to be practical only in case the government built comfortable space stations (or repaired those that had not yet come into complete disrepair). A person singing a contract on their maintenance, had to procure fodder and other items necessary for the maintenance of postal rush at his own expense, without recourse to the deposit.

Speaking about the possibility of the organization of movement of postal coaches in Transcaucasia, N.S.Kakhanov proposed to establish them on the same conditions on which mail coach institutions were kept in Russia — following the example already set up in St. Petersburg, Moscow and Warsaw. He considered it necessary to manifest a special care about the only overland communication route of Transcaucasian region with Russia — Georgian Military Road. Taking into consideration the importance of the tract, he gave the priority of reconstruction to the unsatisfactory postal stations between Tiflis and Vladikavkaz, as well as the overhaul of the road with the simultaneous organization of movement of mail coaches on the tract.

To activate the measures, proposed by N.S.Kakhanov to improve the postal rush in the Transcaucasian region, large funds were required. Just to construct only 13 station buildings, located on the Georgian Military Highway between Tiflis and Vladikavkaz, the estimate provided an amount of 601 891 rubles.

This project had been reviewed by a special commission in 1859 and approved by the vicegerent. Under this approved project it was planned to equip Georgian Military Highway and to establish the movement of postal carriages on it. There were no funds to improve other stations and routes in that period of time.

After the approval of the program to bring the project to fulfillment A.I.Baryatinsky instructed N.S.Kakhanov “to implement his proposed idea.” The construction of station buildings (designed by architect Simonson) was transferred to the contractor — Tiflis citizen Mehdi bey Aga-Usain-Oglu, who had requested a loan of 435,000 rubles on the conditions of thirty-three-year loan and related interest. To acquire the property necessary for first acquisition of “Institutions of postal coaches”, N.S.Kakhanov was sent on a business trip to Russia, Kingdom of Poland and abroad. There he placed an order for the manufacture of 26 four-seater coaches and 26 six-seater omnibuses, 103 vans, 60 sledges and 14 carriages. In 1861, the improvement of the Georgian Military Road was completed, and the tract was opened to the traffic of postal carriages.

Due to lack of funds for the improvement of the other stations of the Tiflis province, they had been left in the same condition, and by the decree to the Senate on April 30, 1861, they were once again handed over to the police department. Thus, as a result of reforms carried out over postal rush, only the stations located on the Georgian Military Highway were left under the management of the Post Office.

Final transfer of the postal stations of the Transcaucasian region from under the management of rural Police to under the management of the Post Office was held only in 1868 on the basis of the decree to the Senate on December 9, 1867 “On the transformation of the Caucasus and the Transcaucasian region.” [31]

Introduction to the South Caucasus, of the “estimated” system of managing post stations, instead of selling them from the “auction” came only since 1871.

City post of Tiflis

Since 1845, the work of the Tiflis province post office became more active. So, in 1845 the office postage fees amounted to 40016 rubles, in 1846 — 40552 rubles, and in 1847 — 46751 rubles. However, despite the increase in the time allotted to get cash-mail packages, letters and parcels, many customers still remained dissatisfied.

In the report to the vicegerent, the manager of the Post Office in the Caucasus I.I.Nazarov reported on January 13, 1848: “Some of the correspondents, losing patience in the queue waiting to register their letters and parcels in the declared book, have to return back very unhappy still keeping them and are forced to send them taking a convenient opportunity of sending, what makes the state treasury suffers damages” [32]

There came a need to establish in Tiflis a city post office to help the provincial post office, as it was already made in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kiev and Odessa. By decree of the vicegerent such post office was temporary established as an experiment. The official announcement about it was published on March 11, 1848, in the newspaper “Transcaucasian Vestnik”, and then on March 13 of the same year in the newspaper “Caucasus”. City Post Office was located on Zion Street in the house of D. Tamamshev and started to work since 15 March 1848.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.