Бесплатный фрагмент - The Org Board. How to Develop a Company Structure

INTRODUCTION

This book was written for the executives and owners of small to medium sized companies that are expanding, as well as anyone who makes decisions regarding the company’s structure and improvements to facilitate business growth and development. It is for those who love what they do and dream of creating a well-organized business.

When I was creating my first business, I was going through one textbook after another on the subject of management in an attempt to find the answer to this question: what is the optimum structure for my company? Without any exaggeration, I spent lots of hours researching but, in the end, was disappointed. In management textbooks I found only very general recommendations, most of which did not go beyond classifying types: the company structure can be of this type, or it can be of that type… I did not find any specific concepts regarding which structure I should choose and what criteria I should use to make that choice. Also, while reading these books, I got the impression that they are written as if one wanted to manage some global corporation from aboard a spacecraft. It was impossible to understand how to apply all these clever ideas to actual operations in a relatively small manufacturing, trading or service company.

I also knew that I would not be able to build a well-managed company if I, the founder and the CEO, didn’t have an initial “blueprint”, basically — no idea of the necessary divisions and levels of employee responsibility. At that time, my manufacturing company was not very big. It had about 150 full-time employees and several independent contractors. My technical education, logic, and experience told me that without a sound organizational structure I would not be able to properly organize and expand the work, just as it would be impossible to build a beautiful building by attaching additional floors, attics, balconies, and garages to a small house. Only with a comprehensive initial plan of the entire building could it be built floor by floor.

As it turned out, this problem had a beautiful and logical solution. It is possible to develop a structure that will provide a solid foundation for organizational expansion and development, while will not changing significantly in the process of growth. As I write this, seven years of consulting and working experience with more than two hundred companies of various specializations confirm that this is not just an elegant theory. It is a real opportunity to create an optimum structure of the company, regardless of its size and stage of business development.

This book is dedicated to one of the fundamental principles of organizing work, which you will use to overcome management difficulties. Regardless the size of your company, while reading this book you will see the great potential of your business as well as the issues which limit its growth and development. You may think you already know this, but I’ll take it upon myself to say that you are mistaken. If you already knew precisely the true potential of your company, and understood its weakest link — you would have already taken care of it.

I often hear from business owners that their weak spot is sales, but experience shows otherwise. Cursory research shows that sales departments function quite well, while instead management is completely oblivious to lack of advertising, or that their products are not competitive. Regardless of whether you agree or not, I promise that you will see your business in a completely new light and gain many new ideas for its expansion.

If you look around, you will find many companies in many different lines of business that have great products, but the scale of their activities has not grown for years. Why do some companies expand rapidly and within ten years go international, while others, despite their outstanding product, settle for a very small share of the market and remain at almost the same level? You will find the answer to this question in my book.

Perhaps, you will thumb through this book and see some data that seems redundant or too complex. However, if you read it consistently and carefully, you will see that these concepts are simple and useful, even for small companies. Their implementation will bring any sized business significant expansion.

After all, your personal point of view on your business fully determines its future. My recommendation is that you read this book in its entirety, and then refer to individual chapters and inserts to gain a greater understanding of specific divisions.

Management is one of the most ancient human endeavors. It can remain simple if you don’t introduce arbitrary complexities. Its basics have remained virtually unchanged since the times when the head of the tribe led his tribesmen out of the caves to hunt mammoths. Of course, modern technology (computers, the Internet, advanced means of communication, etc) gave us an opportunity to eliminate errors from daily tasks, but the basics of managing a group remain the same.

These basics will give you the knowledge to better understand how you can organize a group of people and their work. An adventure is awaiting you. After reading this book you will see your own business and any other company in a different light.

CHAPTER 1

STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT AND CRISES OF THE SMALL BUSINESS

A company goes through several stages in its development; it all starts with the bright idea that answers how you can provide something of value to a certain category of customers.

We can say that this is the research and development phase of a product and its reproduction. In some business fields areas, such a technology already exists or can be acquired; while with others you have to invent or create something new.

At this stage, the company’s founder is often deeply involved with the daily activities of the company and product development. He personally organizes production or arranges delivery of goods. He thoroughly explores and implements the vision of a restaurant, or develops the services for the company. If this stage is successful, it’ll result with the first batch of satisfied customers, and your team gains the confidence that your idea translates to a business. This stage one understands the product’s actual cost, prices are developed and connections are created to get the necessary resources. The product undergoes some improvements or even a complete makeover, and you gain an insight, confirmed by experience, into your customers and distribution channels. At this stage, the company executives are not quite interested in making management as effective as it could be — all the attention is focused on product creation and bolstering a viable company.

We call this the Manual Stage, where the business founder, holding the vision and being competent, manages a small team quite well. He knows the technology for producing the product, as well as what his employees need to achieve in order to get results. As the company engages in small-scale activity, there aren’t executives and management issues do not come up. Regardless, the business is still gradually approaching the First Management Crisis. When the company hits the crisis depends on how fast the company is growing.

Once the idea proves successful and you have to turn it into a real business, then we move to the next stage. The owner begins to understand that to further expand, he needs to shift from directly managing individual employees to managing parts of the company — he needs to create a second level of managers. Whether the business owner promotes his best employees to managers or tries to hire experienced ones, the First Management Crisis deals the inevitable blow. After managers or executives are hired and established, overall efficiency usually drops.

CEOs of smaller companies come to a seemingly logical conclusion that the drop is due to the incompetence of his new hires or their unwillingness to work. Have you ever heard executives complain about employees who don’t want to work? Yet, these same employees had previously produced good results under direct management — and suddenly everything changed.

The real reason is not that people transform overnight, but that the leader– usually, the owner of the company — is only good at directly managing rank and file employees and not his new level of executives. The owner knows the production technology and competently directly guides employees to the desired results. The owner is just not able to effectively manage the executives who must now manage the other employees. It’s one thing to fly a plane, which in itself is not an easy task and requires special skills, but it’s a completely different job to lead a team of pilots. A pilot has to competently handle the machine, an executive needs to competently handle people. Additionally, they use completely different bodies of knowledge and tools.

This is the main reason why small and profitable companies, even those with great products, rarely expand beyond a certain point. They weren’t able to overcome the First Management Crisis and grow out of their small business “pants”. Thousands of examples illustrate the First Management Crisis. One of the most famous is the incredibly successful small family restaurant owned by brothers Dick and Mac McDonald. It was well known locally and produced a steady income for its owners. The brothers made numerous attempts to create a network of fast food restaurants, but it wasn’t until Ray Kroc1 took on the business development that McDonald’s was born.

A lesser known, but no less illustrative example is that of the famous Brooklyn pizzeria Di Fara Pizza who has had the same owner and chef, Domenico DeMarco2, since 1964.

Experts have repeatedly honored DeMarco’s pizza with the highest awards. Yet, despite the outstanding taste and a long line of people outside the restaurant, the facility has not expanded since its opening. Of course, this situation greatly depends on the goals of the business founder. In this example the owner simply doesn’t desire to expand his business. His passion lies in the craft and it seems that he simply likes making pizza without any further ambitions. To get to the next stage of business development, one needs to have the ambition to grow and have big goals. Then there is a chance to overcome this crisis. In my book, The Business Owner Defined, I described, in detail, the objectives of a business. However, to become successful, it is not enough to just have goals for the company executives. There has to be tools, such as a company structure, a system to measure results, financial policies, etc.

A business falls into the First Management Crisis after appointing executives without any management tools. These executives expect the owner to utilize the same hands-on control, but in a more difficult condition as the company has grown. Additionally, the owner now tries to manage “manually” at a new level, which is usually unsuccessful, and so the chaos grows. In order to overcome the crisis, the founder of the company must master the tools for managing people, train strong leaders, and learn to manage effectively.

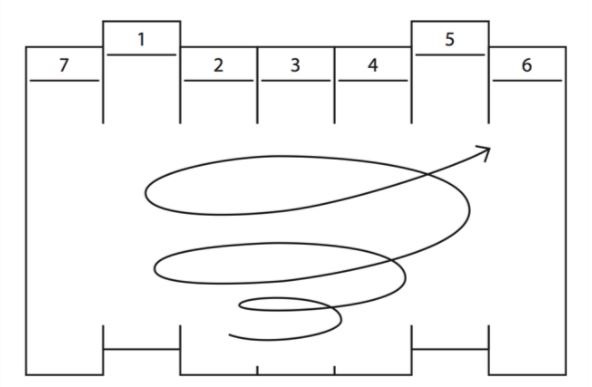

Once the first crisis is handled, the company will continue to grow and that may continue for many years. But interestingly enough, sooner or later the founder of the company will feel the need to switch out managing the daily operations for carrying out strategic management while remaining the goal setter.

To win a large-scale battle, one needs to be on an elevated plane where they can view the whole battlefield and the surrounding area. Therefore, can properly plan one’s own actions and anticipate the actions of the enemy. It is impossible to intelligently manage a large-scale activity being in the thick of things at the forefront. The second management crisis has to do with the inevitable need to take on the functions of a strategist to direct the activities of a well-organized company. The owner must go from operational management to strategic.

Often it is the desire to move away from daily operations (the front of the battle) that encourages owners to implement management tools. However, one needs to realize that simply adding an organizing board and other tools will not facilitate the switch on their own; they will only create the necessary foundation. After you implement the management tools, you need to cultivate competent executives, and only then can you delegate the management of operations. If you go about this with an intelligent plan, you could implement management tools in a small business in six months to a year, and cultivate your executives within a year. This is a big job. You will have to invest as much time and effort as you would in establishing your technological processes. But the game is worth your while — the company will not only become well-managed, it will also gain a significant advantage over its competition.

CHAPTER 2

VALUABLE FINAL PRODUCT

The Valuable Final Product (abbreviated to VFP) is one of the key management concepts defined by L. Ron Hubbard in his articles. You see this all the time — your employees perform lots of actions, but not all of them are actually directed towards results. Or you see how someone is always preparing to do a job: he arranges his papers, organizes the computer files, he invents clever ways to organize his desk tools, etc. Another employee is running around crazed and completing one thing after the other. He may look busy, but he’s still not producing the results you expected. Why is this happening? Why do we have those who produce results and those who are busy with “doingness”?

In the dictionary, we can find the following definition for product, “an artifact that has been created by someone or some process” where artifact is “a man-made object taken as a whole”. An accountant prepares a report and sends it to the IRS, that is definitely a product. When a barista puts the final touches on a cup of coffee and hands it to the customer — that is also a product. When the owner of a company develops a strategy, by spending his time and energy on it, and describes it in a document that can then be studied by his executives — the strategy here is a product.

Note that the word object means “a tangible and visible entity”, where tangible means that it can be perceived by the senses as something that exists. Therefore, somebody’s brilliant plan that is not shared with anyone is not a product because other people cannot perceive it, unless they are able to read the person’s mind. For that plan to become a product, it has to be at least shared with someone, and then it will become a product. The product is always tangible, even when it comes to such “intangible” things as designs, plans, and ideas. They need to be described on paper or introduced during presentations — otherwise they are not products. A motivational meeting that inspires employees to succeed is a great product for an executive, as the change in employee attitude is quite tangible — you can see and feel it. But the product that is not noticeable to others, by definition, cannot be a product. If the, “I was trying”, “I attempted to”, “I was getting ready to”, etc don’t result into something that can be perceived by the senses, it’s not a product.

Everybody has many products in their various areas of their life. Even an employee who sharpened their pencil would have a product, as you can definitely perceive it with the senses and it is a result of work.

Work, by definition, is a conscious activity with a certain purpose. For example, a sales manager wanted to close his client on a deal for equipment supply, but instead spent his time educating the client in some technical issues. If his goal was to sell, then he was directing his efforts towards one result, but achieved a different one. Therefore, educating the customer was not a product, unless, of course, he had planned to engage in such educational activities.

If an executive created a pay system designed to improve productivity, but resulted in employee dissatisfaction and loss of personnel, then this system is not a product as it doesn’t align with the set goals. The HR manager hires an employee who stays in the company for a week and then runs away — this new employee is not a product as it deviated from the goal of hiring a new person. On the other hand, hiring an employee that improves the company’s production, would be a product.

Any product must be completed to be considered a product. A salesman, whose goal is to close the deal, attracts a customer who demands discounts and special treatment, so that the executive winds up personally closing the sale, didn’t get a product. If the company’s goal setter conceives a brilliant plan, but does not describe it in sufficient enough detail so that it can be given to his executives to work on — this is not a final product. If the person assigned to the product doesn’t complete it in such a way that it can be used, someone will have to “finalize” it, which creates additional work for others.

Usually, having to “finalize” a product results in a lot of unnecessary and additional actions, and devours the production time of employees. If you examine some employee’s actions, you will see that most of their time is spent either completing other people’s products or correcting the consequences of such incompleteness. For example, you ask an employee to pay a contractor for his work. Your Accounting Department starts working on it, but a week later the contractor is calling you, upset by the fact that he did not get paid. Now, you’re taking the time to handle the contractor, re-issuing the order, and convincing the contractor to continue doing business with you despite the agreement violation. The contractor may cease doing business with your company, and you’ll have to find a new one. All the while, spend time restoring your reputation in the community. You’ve wasted a lot of production time because of one very simple, but incomplete product of the Accounting Department. Why did the Account Department slack in this task? The accountant simply does not understand what his “final product” is.

I don’t know if you are aware of the scope of this issue, but it is huge. In an article on management3, I came across the idea that a person who doesn’t understand his product, would not be able to produce it. As a practical man, I decided to check how well my executives understand their final products. I simply asked each of them, “What do you think is the primary result or product of your position?” The answers I got from interviewing a dozen of my executives were rather shocking. They were naming lots of things as their product, but not at all the product that I expected from them. When one of the executives told me, “My product is to have my manager help me,” I quit surveying. After that I made a decision — I am not going to ask any more questions, instead I will name the exact product for each of my subordinates and make sure that they fully understand it. And don’t get the idea, by the way, that I got that answer from a totally useless executive or that the company was no good. The company was an industry leader and that executive was quite a good worker. The answer was so absurd, that it wouldn’t have even occurred to me! If you have a strong stomach, try surveying your employees or co-workers. This will be an adventure! Ask them what they consider their main product to be and you will start understanding them better.

Another very important factor is how valuable is the product that a person produces. Value is the degree of importance, which can be often, but not always, expressed in monetary value. A glass of water, for example, will take on a completely different value to you depending on whether you are in the hot desert or sitting in a cool office. The value is not determined by the amount of labor or materials that went into it, but rather by the desire — meaning, how badly others want to get this product and what they are willing to give in exchange. On a hot summer day the value of an ice cream cone is high while during a cold winter, it is low. And here’s something important about this concept: you don’t always view something useful as having a real value. For example, every man’s future depends to a great extent on the kindergarten and school teachers they had when they were growing up. But the paradox is that in this society, it is not customary to pay a lot of money for the products of teachers…

This is a very old and odd tradition, but it is nonetheless true. At the same time, people are willing to pay a considerable amount of money for the advice of a lawyer or stockbroker. Hard to believe? Take a look at how much people spend on designer clothes and beautiful cars, and how much they spend on education and upbringing of their children. How much effort and money they spend to kill themselves in various ways, and how much to promote their health. I’m not talking now about a special medical treatment when they are willing to give all they have, but about keeping a healthy lifestyle. I’m not trying to give you a hard time, but just so you understand that the value of a product is not always logical, it depends on opinions of others. For a product to be called “valuable” other people have to want it and it needs to be valuable to them. Our civilization is neither perfectly fair nor balanced — there are some odd values and you should be aware of that. Apparently, the ability to understand, and especially to predict, what would be valuable to people is one of the greatest components of an entrepreneur.

When we talk about the value of an employee’s product, we mean the degree in which what he produces is needed by the company. If the company wants HR to hire effective employees, then the value isn’t how many people and how quickly HR fills the vacancies. Ultimately, it is how successful and productive the new hires are. If a leader creates inspiring goals and directs the team members towards these goals, this is valuable to each member of the group. This is why people will follow leaders, join their goals, and are willing to provide their own creativity and efforts in exchange for that value.

Each life role or job position has a certain Valuable Final Products (VFP). For example, the VFP of a salesperson is signed and paid contracts; the VFP of an HR manager is productive employees who are established on their jobs; the VFP of a CEO is an expanding and thriving company that produces a valuable product for its clients. The VFPs of a husband is a family that is safe, secure, and provided for financially. The conscious production of a product starts when a person understands exactly what their valuable final product is. If the person lacks that understanding, they will produce something that he personally considers valuable, or he will follow personal inclinations. When we carry out our consulting projects, we ask our business owners to conduct a survey with their key employees and managers to ask them what they consider their product to be. When the survey results are in, the executives clutch their heads in despair. The odd employee ideas that the survey reveals can be rather astounding. If you do the surveys, you will find out that no more than 10% of the company’s employees can accurately name their VFP. This is bad. If they can’t properly identify it, they cannot focus their efforts on producing it. To compensate for it, you’ll give out individual orders and constantly direct the employee to produce his VFP. That is inefficient. The upside is that the productivity of employees can be significantly improved once you give them an accurate understanding of their VFP. This principle is also applicable outside of business; many couples could improve their marriage if they simply worked out with their partner the exact VFP they expect from each other.

An accountant who doesn’t understand that one of their most important VFPs is securing the value of company’s assets (money, property, materials and goods), will keep asset records as a formality and you will not be able to keep track of the actual condition of your assets. If a lawyer does not understand that his VFP is legal security of the company, he will not take the initiative to check over every agreement, to ensure that the company has sound employment contracts, and financial liability agreements for its employees. Instead, he will simply draft and check over the contracts that come his way, while legal security will be rest upon the shoulders of those who “stick their nose” into everyone’s business, i.e. the top executives.

“A Valuable Final Product something that can be exchanged with other activities in return for support. The support usually adds up to food, clothing, shelter, money, tolerance and cooperation (goodwill)”. 4

Give your employees a clear understanding of the VFP you expect from them and they will either greatly enhance their performance or refuse to do the work. Don’t be surprised if you get a letter of resignation from an employee after you’ve defined his VPF. Perhaps, he never intended to produce this particular product, and the executive’s expectations were in vain. This rarely happens, as most people like working with awareness, purpose, and want to produce something truly valuable. Perhaps not everybody will like this, but what does that matter? There are lots of successful people who could work in your company.

When formulating a VFP, note that it should be: actual results of completed work, an item (perceived by the senses), should always be fully complete, and, above all, valuable to the company. The last thing to remember, before giving a person their VFP, is you must have a clear understanding of what exactly you want to get from him.

Try to formulate the VFPs for various employees that work near you and then watch what they are actually working on. For many of the posts, you will easily name their product but for some could be unclear. If you’re finding it difficult to formulate these VFPs, I can assure you that your employees are even less clear on what should their work results. It’s not at all surprising that most HR managers believe that their product is “hired employees”, while executives expect them to provide “productive employees”. While advertising specialists believe their product is creating a “memorable advertisement” rather than, “people who walk into the store as a result of the advertisement”.

A VFP is applied to a particular position, but can also be applied to projects, a task or an order. It’s quite appropriate to accurately define the VFP of a task you assign. Defining a VFP will result in less “almost dones” from your employees. Good production in any field starts with a clear understanding of the result that needs to be obtained.

CHAPTER 3

THE PRODUCT OF A COMPANY

A professional in a specialized field, such as a chef or painter, can easily tell you their VFP. They would even be surprised you asked them about it. While with executives, you will often find that instead of their product, they list the actions they perform. Department heads will confidently tell you that their products are, “well-organized work”, “high performance” or even “ensuring employees are provided with everything they need to do their jobs”. But that is not it! The VFP of an executive is what his entire department produces.

Take a crew of house painters as an example. A foreman will plan, assign tasks, ensure that the work gets done, coordinate the actions of the team with other departments, and perform many other functions. This activity is the “doingness”. The VFP of a worker in his crew is obvious: painted walls. He has several workers who produce this VFP and he, as manager, is running the activity. His own VFP is the VFP of all the workers as a whole, i.e. the VFP of the whole crew. Once this is understood, it is not difficult to formulate his VFP as, “professional quality painting jobs completed on time”. The foreman’s customers are expecting this product and willingly pay specifically for that. If a foreman can’t get that VFP through executive actions, such as orders or assigning tasks, he simply picks up a brush and begins to paint the walls himself. He could at least achieve the crew’s VFP in that fashion.

In a similar vein, if the head of a company cannot get the company’s VFP produced through executive means, he rolls up the sleeves and finds customers, makes sales, creates advertisements, handles unhappy customers, etc. He does all this because he is responsible for the VFP of the company as a whole. Executives, as a rule, are responsible people, and, quite often, experts in the area they manage. Unfortunately, their expertise thwarts their ability to be good executives, and instead of learning and using management tools, they do the work of their juniors. It may seem very responsible to take the initiative and show an employee how to do the work. But in that moment when the executive demonstrates his wall-painting mastery, nobody is doing the job of the executive… Usually, an executive can replace his juniors, but not vice versa.

Imagine the foreman of a crew of a couple dozen painters, and, instead of ensuring productive and well-coordinated work, he personally takes a brush to the wall. Good control of workers can significantly increase the crew’s performance, compared to simply being an extra pair of hands. A competent sales manager with five salespeople in his department can significantly increase the sales volume if he plans the work out, sets targets, supervises the work, corrects errors, and demands results rather than personally closing the sales.

If you understand this principle, you can even determine whether the person you want to hire would make a good executive. Just ask him what he thinks his VFP as an executive is, and find out how well he understands the tools he should use as an executive to produce that product.

If you are the owner or the CEO of a company, your product is the VFP of your entire company. And that helps assess your own performance. For example, my main VFP as the founder of Visotsky Consulting is management tools implemented in our clients’ enterprises. If my company implements them correctly, it leads to the expansion of their businesses, which means that I produce my product. If my company takes on a project and does not accomplish that result, I have not produced the VFP.

Determining the VFP of your business is quite simple. It’s the specific product or service for which your customers pay you money. If the business deals with window manufacturing and installation, the CEO’s VFP can be stated as, “windows of high-quality manufactured and installed”. Of course, you need to clearly understand what the client is paying you money for. As an example, what do customers pay money for at a restaurant? Delicious food, atmosphere, speedy service, and a convenient location. Look at several restaurants, and you will find that they have completely different VFPs. There are restaurants that boast famous dishes where clients will travel great distances and reserve a table months prior just to eat there. There are restaurants known for their special ambiance, and restaurants where you expect to eat quickly.

Even in a relatively successful business, sometimes the executive does not understand the VFP of the company, and, therefore, his own VFP. Two years ago, I visited a restaurant that served Russian cuisine about 6 miles outside a small Russian town. The restaurant was unique because they grew their own delicious vegetables and herbs, and the interior of the restaurant consisted of separate rooms that emulated the rooms of an ordinary residential house from the Soviet period. No two rooms looked the same and each guest was greeted by the waiter who acted as the owner of the house. Having dinner there was more like visiting the house of your hospitable friends rather than a restaurant. Even though I’d eaten in many Russian restaurants, I’d never tasted such delicious Russian cuisine. That restaurant became extremely popular and well known in the city, and generated a decent income for its owner. After several years of business success, the owner decided to expand the business and opened a restaurant in a resort town by the sea. She invested all her savings in this new restaurant that was completely different from the original. It had neither its own vegetable garden nor the unique rooms. She transferred the chef and the best waiters to the new restaurant, and within a year she experienced nothing but losses. Moreover, the lack of attention to running the first restaurant, loss of qualified staff, and cutting operating expenses resulted in a significant decline of the business.

I don’t know what her motivation was — maybe her dream was to retire by the sea. But from a business perspective, it wasn’t a smart decision. The reason for her failure is simple — she had never considered what the VFP of her old successful restaurant was, and what the new VFP should have been. People came to the old restaurant for a special meal and the ambiance. Visiting this restaurant was an event in itself, and customers willingly traveled several miles for the experience. The new restaurant was nothing like that. It only had the good recipes from the original restaurant, but without the supply of special fresh produce and the unique setting. This new restaurant, which was actually one of many located in the neighborhood, had a completely different VFP. Lack of understanding of the exact product the client is paying for resulted in her almost losing the business.

Retail companies have their own VFP, and it is not the merchandise they sell. By definition, the VFP is what a person produces, and retail companies do not produce the merchandise itself. Retailers “produce” the availability of a product to the customer. Trading and retail activities always entail providing a certain selection of goods at a particular location, plus some additional services. That is why in retail it is so important to assess the selection of goods provided in relation to the location. Duane Reade5 stores offer their customers a limited range of everyday products conveniently located so that they could drop in during their commute. Macy’s6 department stores offer their customers a wide selection of inexpensive clothing and household goods. You do not stop there on your way home. You go there to buy a summer dress and end up leaving tired, with stuffed shopping bags that barely fit in the back seat of your car. Both of these are in the retail business but they have very different VFPs. And what’s interesting, is that in both examples the function of selling the merchandise is practically nonexistent, as they are self-service stores. It would be erroneous to state that the VFP of these stores were “sold goods” when they don’t take effort to sell, i.e. to exchange goods for money. By selling, I mean conscious actions of a salesperson that lead to a customer making a single purchase or purchasing more items. Yet, these stores consistently and successfully create a selection of goods wanted by their customers and correctly present them so their customer can easily find the right product by himself. They ensure that the store’s location is convenient, and that the product’s price and quality meet clients’ expectations.

If you haven’t been to the Apple Store on 5th Avenue in New York, you should stop by and you’ll see that nobody sells anything there either. The store’s staff offer advice, demonstrate products, answer customers’ questions, do the checkout, and hand over purchases to the buyer. However, they do not persuade the customer to buy the product or handle their objections. Apple has created such a compelling product, that during the Christmas season, customers have to squeeze through the crowded store to stand in a humongous line for the treasured box with a new iPhone or iPad. This store is a hybrid of a showroom and a warehouse. The difference from a showroom lies the large number of consultants and being able to pay for merchandise right on the sales floor.

Another example of a special VFP in a retail company, similar to the Apple store, is B&H Superstore of digital equipment in Manhattan. They have solved the problem of selling a large variety of sophisticated digital equipment in a relatively small space. The way the shop is set up, a client can get familiar with the equipment, get expert advice from the employees, as well as quickly pay and get the products they want. To display an array of equipment without overloading the area with stored goods, B&H installed a conveyor belt right below the ceiling of the sales area. It quickly delivers the desired items from the warehouse into the customer’s hands. It’s surprising that B&H has not yet become a well-known franchise. The volume of the VFP of these stores is something to truly admire. What is the VFP of such a store? Not of the company as a whole, but of a store, specifically? The VFP will definitely include wording such as, “assistance with making a choice”, “speed”, and “a certain selection of goods”.

It does not matter whether one is managing just a single division or an entire company, if they don’t understand the group’s VFP, sooner or later, they will fail. In about 50% of my consulting projects, I found that even the founder of the company did not have a clear understanding of the product the client was paying him for. If you’re an expert skier, are knowledgeable in the subject, and have been selling ski gear for more than 10 years, then your understanding of what is valuable may differ significantly from the viewpoint of the majority of customers in your store. This is because most of your buyers are beginners who are just taking their first steps. Beginners are the ones who tend to buy most of the equipment and gear, not those who have been skiing for years. Experienced skiers already have their “tried and true” gear that they keep throughout the seasons.

Finding out what holds value for your customers is simple through the use of surveys. A customer survey asks them what is valuable, important and what is missing for them in your product. This survey is not for promotion purposes, but its results are necessary to understand the client’s point of view. When conducting the survey, ask about the product’s shortcomings, because shortcomings and values are two sides of the same coin. If the responses say that they do not like slow service, that means that fast service is valuable. If they say that pricing isn’t clear and that annoys them, then a simple pricing system would be valuable. Think of The Dollar Store or The Dollar Tree — they can be found in any city because their VFP is in demand and have their own clientele.

It is not always easy to objectively look at the results of these surveys. It took me a couple of years to agree with the survey results from our own clients. When I took my first steps in consulting as a business lecturer and owner of a training company, we were conducting great seminars where we taught management tools to business owners and managers. The seminars were attended by thousands of people every year. We had great reviews where they talked about how they wanted to change something in the way their business was organized or how much they liked the ideas we taught them.

But when I analyzed statistical data, it turned out that the average client attended two to four seminars and then stopped attending. Some customers had even booked one or more corporate seminars, but after some time they stopped working with us. Those great reviews they initially gave us after the seminars did not allow us to see the actual situation. Naturally, we waited until we were not doing so well, the number of seminar attendees declined, and it became increasingly more difficult to fill events. Only then did we conduct surveys about the VFP of our company.

It turned out that the clients who wanted to organize the workflow in their businesses and could pay for our services, were not getting what they had expected. We didn’t meet their expectations of implementing management tools. When they came to our seminars, they had hoped to implement the management tools in their organization and, consequently, improve its performance. However, in most cases that wasn’t the way it turned out.

We conducted customer surveys regarding the value of our product and it was particularly valuable and important to interview two categories of clients:

• Those who continued to pay us. They were asked about the value they acquired from receiving our services;

• Those who had been paying us for some time and then stopped. They were asked about what they expected to receive, but did not receive, or about what we needed to improve in our products.

Once I analyzed the survey results, I came to the conclusion that the only real value for our clients was in implementing management tools in their enterprises. That study was the impetus that led to the founding of “Visotsky Consulting”.

Such a survey can be done in any business. Of course, you will need to customize the questions for the particular business. For example, in a store, I would ask the buyers why they chose this store for their purchases, and in what circumstances and why would they choose to buy at other stores. It makes sense to ask these questions for businesses where competitors have similar products. If the service is unique, such as a singing coach, one would ask what the clients liked and disliked the most about your services. You will find that people, especially those with positive attitudes, do not like to talk about the negative aspects of things. In order to ferret out this information, you have to resort to various tricks. In such cases, I say that my job is to improve the company’s performance, and that they would be helping me out if they were to tell me what we should improve in our product.

It requires a certain amount of courage to conduct these kinds of surveys. An executive who loves his job is unlikely to be pleased when he discovers some of the shortcomings in his product. Does anyone enjoy it when somebody bursts their bubble? But if we don’t understand what is valuable about our product, how can we effectively reproduce it? Just look at it this way, every shortcoming detected by the survey is a new opportunity to improve the company. If your company is already successfully providing the valuable product to its customers, any increase in the value of this product can bring you a considerable increase in income.

If your company or division has several completely different types of customers or products, you will have to conduct multiple surveys. For example, you sell electric tools both wholesale and through your own retail stores. Essentially, you have two different products. In this case, these two different VFPs will provide two different types of clients, one type for each product. The easiest way to survey the retail customers is in a store. As far as the wholesalers, you will most likely have to survey them by phone.

Here’s one of the secrets to successfully conducting surveys on the product’s value — do not give clients a survey to fill out. In this case, a written survey will not yield usable responses and is a waste of time and money. For a survey with usable answers, you need personal contact. And since this survey regards the company’s product that you are personally responsible for, I recommend that you do it yourself. This may sound strange, but my experience shows that when such a survey is done by employees, they miss very important details and the survey loses some of its value. The good news is that you do not need to survey hundreds of clients. From experience, it is sufficient to survey just a dozen or two. If you ask the correct questions and elicit honest answers, you will find that the responses are very similar. Another advantage of doing the survey yourself, is that the clients respond much more readily and openly to the head of the company, which greatly speeds up the process.

So, write the questions for your survey. Then head to the sales department and get a list of customers who: have recently bought something and those who stopped buying. Or you can simply go down to the retail sales space or office to take action. You are in for an adventure! Most likely, you will learn something new about your own VFP, and you will get a much clearer and precise picture of it. Then you will be able to tell the staff about the results of your study. When you convey to them exactly what the company or division’s VFP is, you will find that that one action improves performance.

CHAPTER 4

PRODUCT AND TYPES OF EXCHANGE

I often see phrases such as, “a satisfied customer”, “high-quality service”, or “a customer who comes again and brings friends” in the wording of a company product. However, this phrasing doesn’t convey the product’s value, they only declare the intention to do a job well. When customers order services or buy products, they expect a specific thing. Ask yourself, when you go to the dentist, what do you want to get for your money? In any business, we strive to satisfy our customer. The value of that is obvious — customer satisfaction strengthens the company’s image and helps ease our work. But the customer doesn’t pay for happiness, he pays for a specific value. The dentist gives us beautiful and healthy teeth, plus a comfortable treatment with long-lasting results. We don’t pay him simply because we are “satisfied and will come back to him.”

Another dangerous term in product wordings is “high-quality”. It should only be used when an industry has particular standards that are generally known and understood. Otherwise the customer’s understanding of “high-quality” can be completely different from the employee’s understanding.

When I was consulting printing companies, I found that the company and its customers had different ideas on what was considered “high-quality printing”. These differences created a lot of problems when orders were delivered to customers. When the VFP of the company was worked out and phrased as, “printing jobs performed on time and in accordance with ISO standards”7, and helpful references were added to all customer handouts, a clear understanding between the company and customer was achieved. To determine whether the printed product conformed to the international standards, one just had to perform a few simple measurements — such as determining the variance of halftone in printing. Only you can determine what is acceptable and what is not acceptable for your business. In our consulting projects, I ask executives questions that guide them to defining what is an acceptable product and what is not. If it’s a retail company, then what selection of goods should it have? What is the acceptable delivery or processing time? Would you consider a partially completed order to be a final product? What technical standards will allow you to determine whether you have succeeded in producing the product? What orders will be rejected on the basis that our technology can’t provide a high-quality product?

To understand the company’s product, it is also important to understand what it is not. If McDonald’s tried to please a different kind of customer and add menu items for them, they would end up losing the speed and efficiency they’re known for — and quickly start losing customers. You don’t like the food from McDonald’s? You are just not their customer. Their VFP is meant for another type of customer, and millions currently go to McDonald’s because they’re happy with it.

There are no absolute good or bad products. When one buys $20 sneakers from Walmart, they don’t expect them to withstand the same wear and tear, nor be a comfortable, as a new $100 Nike pair. Yet, both sell well and are in demand by different types of customers — each model makes their respective customers happy. It may be that Walmart sells more of their sneakers than Nike. Simple sneakers from Walmart is one VFP, Nike shoes is another one. It is important to understand what exact product we provide for our customers, and what we don’t.

Perhaps, thinking this over, you find that you don’t always successfully provide your clients with the VFP that you consider acceptable. Don’t worry, this means only one thing — your business has a great and untapped potential. This book will help you build an organization that produces the desired result. But to produce it, the VFP needs to be precisely stated and its wording should be known to each employee.

Today, there is a lot of talk of how business success depends on sound leadership, management, investments, marketing, promotion, and other factors. Examining these, logic tells us that not all of these components are equally important. What is the foundation on which you can start building an outstanding company? From my viewpoint, it is the ability of the business to produce a good, in-demand VFP. Every day you and I receive many offers to buy, but how many restaurants do you consider to be really good and cater to your taste? How many clothing stores can buy clothes that meet your needs? How easy is it for you to find a construction company that will perfectly perform the job well?

An important principle which business success is based upon, is maintaining a fair exchange of values between the company and the client. In one of his articles8, L. Ron Hubbard describes the four basic conditions of exchange: • Exchange in Abundance • Fair Exchange • Partial Exchange • Criminal Exchange

Generally, businesses will strive to provide fair exchange with their customers. This is where, from the viewpoint of the client and the company, the value of the product and the money paid is equal. A customer expects to pay approximately $12 for his workday lunch. He also wants to enjoy a delicious meal within 45 minutes. If the diner meets those three points, he’ll view it as an fair exchange. A client places an order for booklets in a print shop. He agrees on the date and location of the delivery, costs, and packaging. He gets his booklets on time that meet his quality expectations. When the client receives a fair exchange, he is usually happy and will continue the business relationship. Obviously, the desire to continue doing business with a company will not depend on the company’s concept of exchange, rather it’ll depend on the client’s conception.

What happens when the client, does not receive, their opinion, a fair exchange? How do you feel when you planned on a 45 minute lunch, but you waited for over 30 minutes for your food to arrive, which left you only 10 minutes to hastily swallow the food, and then run back to work? You immediately want to end the exchange — you even reduce the waiter’s tip or declare you’ll never come back. This occurs because the diner gave a partial exchange. When we feel that we receive a partial exchange, our natural urge is to stop this exchange. It’s for this reason, by the way, that in the previous chapter I strongly recommended doing surveys on the value of the product your company provides. When a client picking out clothes in a store can’t get the sales assistant to help him find the right size, or the lines to the fitting rooms are too long, they will get frustrated due to a partial exchange.

It’s funny how a crowd can influence the client’s concept of exchange. Examine this phenomena by going to a very popular store during a sale — try Macy’s on Memorial Day weekend, or an Apple store immediately after they release the new i-something. While standing in a line with over 30 people in a tightly packed room, you get the feeling that you are buying something extremely valuable. Apparently, nothing increases the value of the product like a huge line going out the door. Note, that the product itself has not changed, only the opinion about its value has changed.

This is the basis for the high value of luxury9 goods. One of the main components that creates their value is inaccessibility due to high cost. The high price is not arbitrary. Their actual value is very high and owning products of this caliber symbolizes the owner’s status. It’s not based on the composite value of the materials. They are expensive because they give that status to their owner.

If the company provides customers with a partial exchange, day after day, it will corrode the business like rust. They’ll consistently lose their clients, and they’ll have to compensate for these losses with additional efforts and costs to sell the VFP. The cost of acquiring a new customer in different types of businesses can range from a few dollars to thousands. Ten years ago, I calculated the cost of getting a new client in my company that produced trophies and souvenirs. I simply added up the expenses of annual advertising dedicated to attracting new clients, the salary of our advertising specialist, added reasonable administrative and office expenses, and then divided the result by the number of new clients we attracted through advertising for the year. The result astonished me. It turns out that the cost of attracting one client was more than $250, and the average order from such a client brought in about the same amount. This means that a client who placed only one order with the company, in fact, did not bring us any profit. That one order merely compensated for our costs, and we would only be able to make a profit when he placed the next order. Therefore, our earnings fully depended on the quality of exchange we provided to clients. And if the exchange was partial, even with our prices comparable to the competitor prices, we would be pouring money down the drain every day.

I am sure you’ve heard of start-up businesses with a problem of insufficient initial investments. Lack of money, at first, is just one of the reasons why a company doesn’t produce a valuable enough product. This is usually justified with the hope that first you need to earn some money, and then with that money you can improve the product. The problem here is that it’s virtually impossible to profit off a product that is insufficiently valuable. Partial exchange with clients kills earnings, which forces us to make too many additional expenditures to make up the difference, and, at first, we don’t even realize we’re doing this. For example, you open a bedding store. You have limited resources, but nevertheless you find the money for renovations, equipment, the merchandise to fill the shelves, and the initial promotions. What will happen if you promote this new store, but can’t guarantee a sufficient selection of goods on the shelves and the warehouse? A well-known maxim says, “You never get a second chance to make a first impression,” and this is very true. By not providing the VFP from the very beginning, we are not just wasting money on advertising — no, the situation is much worse. The better advertising works, the worse the long-term outcome will be. Because those who respond to your advertising are your best and quickest customers from your target market, and they’ll become the opinion leaders for others. By not ensuring proper inventory on the shelves, we will definitely provide them with a partial exchange and create a bad impression about the store.

With partial exchange, advertising becomes difficult, sales become complicated and require incredible skills from personnel, and the company has to pay for all that. Executives at all levels have to handle the ensuing customer dissatisfaction. The rumors about dissatisfied customers demoralize the entire company, especially the sales people. If CEOs took the time to calculate how much their business loses when it doesn’t provide fair exchange, they would wage war for the quality of service10. Try to carefully observe the chain of consequences that arises when a company provides partial exchange to its customers, and quantify them in monetary terms. You will be shocked and probably will want to fix it immediately.

One of our recent cases, is a company which supplies, installs, and puts into operation manufacturing facilities. Customer surveys showed that, in general, they were quite happy with the way the company carried out its contracts with only one “but”. They wanted the company to keep sufficient quantities of small spare parts at the warehouse, so they didn’t have to submit their orders for parts in advance and wait for a long time. Yet, for the equipment supplier, it was not profitable to keep such a warehouse and sell inexpensive spare parts. It would require stocking a large assortment of goods for sales that are difficult to predict, as well as additional skilled sales personnel.

Simple calculations showed that the company would not be able to make a substantial profit by selling these spare parts. However, the head of the company explored the consequences of not having such a warehouse. He would have to handle customer dissatisfaction caused by equipment downtime. It would also leave the client open to the competition if they had the part that we did not. Competitors would offer the initial parts, and then the all of the equipment. Then he calculated the magnitude of consequences in monetary terms and immediately decided to establish a unit for selling spare parts for the equipment. By doing so, he basically raised the value of the company’s product and restored the exchange.

Another way a company falls into the trap of giving partial exchange is that the customers’ concept of fair and equal are constantly changing. In some business fields, this happens slowly, in others, lightning fast, but this change occurs everywhere. In the restaurant business it happens slowly, while in high-tech quite quickly. Why didn’t videophones take over for regular phones, but rather they got replaced by Skype and Google Talk? Because telephone companies around the world missed the moment when the consumers’ idea of what was a fair exchange for phone and video calls has changed. Telephone companies could not or did not want to create products that provided fair exchange, so today we pay for internet services much more than we pay for a landline telephone connection. By the way, mobile service providers are next in line. If they don’t become flexible in changing their products with regards to data transmission, so that the consumer does not have to think twice on whether to use a cell phone or call via Skype or Google Talk, they will also gradually become internet providers instead of communication providers. Regardless of the size of a business, be it a nationwide company or a budding entrepreneur, it is necessary to regularly conduct surveys on the value of the product they deliver. Otherwise, what initially was a fair exchange will inevitably drop to partial.

Criminal exchange is actually the absence of exchange. This form of exchange is used by criminals when they receive something, but provide nothing in return. This form of exchange is punishable by law and has nothing to do with business.

The most appealing form of exchange, which is preferable to use in business, is exchange in abundance. In this case, the client receives more than he expected. Many companies are trying to provide their customers with this type of exchange. However, it is important to understand that this exchange is only possible if the client already received a fair exchange. If a restaurant customer did not get his food or service at a desired quality, then even a complement from the chef will not make him any happier. If a construction company did not complete the job on time, than even additional service will not create exchange in abundance. If a customer comes into the store during a sale expecting to get a considerable discount, then half-off on the merchandise will not be perceived as exchange in abundance.

For example, many trendy clothing stores have huge Christmas sales, but while the sale is going on they remove their most popular items from the shelves. If the buyer notices that, he will not feel that he is getting exchange in abundance. If before the sale, the buyer laid eyes on the perfect coat, then went to the store during the sale and the coat was gone, he definitely would not feel that he was given something valuable in the form of a discount. Rather, he would be upset and have a feeling of partial exchange. Exchange in abundance is something that exceeds the client’s normal expectations.

Discounts and sales are actually a dangerous thing. If a customer bought a product or service at a regular price, but after a while he finds out that the same item can be purchased much cheaper, he can get the feeling he received a partial exchange, even though at the time of the purchase he was completely satisfied. At the time of the purchase, he received fair exchange, but then a significant price reduction some time later gives him the idea that he had actually overpaid. Apple is a good example of a smart pricing policy — they reduce their product prices only after they release a new and more attractive model. They do not give discounts and they don’t hold sales. In general, to correctly lower prices, it has to be somehow justified. Otherwise, it will disappoint the most important customers, those who have already paid us money.

If we are able to provide the basic expectations and then provide an additional perk, this increases the client’s desire to deal with the company. Does this make sense? An unexpected additional service or a gift does not just make a person happy, but also gives them a reason to express their gratitude by recommending the company to their friends, writing a good review on social media, or simply coming back. A glass of champagne upon checking-in at a hotel, a holiday gift for the client’s child, a bonus for the next order, a cup of coffee, a small birthday gift, etc. reinforce a positive attitude towards the company. One can easily calculate the benefit of these small acts in terms of money: how much money do you save if your next sale to this customer requires half the advertising expenses, time, and salesman efforts? And this is the way exchange in abundance works. This form of exchange has also a flip side — it gradually increases the customers’ expectations. What at first was exchange in abundance, over time starts to be perceived as fair exchange. If your hotel always welcomes guests with a glass of champagne, then after some time, for your regular customers this will become just a regular fair exchange. You must be ready for that. Therefore, you should never stop working on improving and updating your VFP.

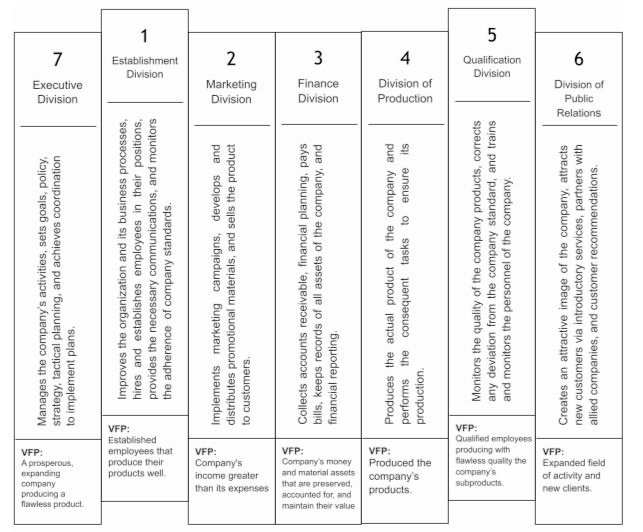

CHAPTER 5

ORGANIZATION

An organization is a certain set of specialized functions performed by individual employees or entire divisions in coordination with each other. By function we mean the certain activity or responsibility of an employee or division. For example, greeting clients as they enter the office and promptly directing them to the appropriate specialist, is a receptionist’s function. While a salesperson’s function is closing deals and getting payments. Each function has its own VFP. For a receptionist it is, “visitors, telephone calls and messages promptly directed to appropriate specialists”. The VFP of a salesman is a “closed deal” or a “received payment”.

An organization begins with the employee who has well-defined and clear functions, and who also knows the functions and products of other employees and divisions. In the chapter on the stages of development of a company, I mentioned the tiny Di Fara Pizza. Their pizza has garnered awards for its quality and has became known all over the world (Google this name if you are curious). However, it has not expanded since 1964. This restaurant never became a full-fledged organization because its founder — a talented Italian chef — performs all the basic business functions himself. There is practically no separation of functions. The founder of the company tries to his hands on everything. As a result, he gets carried away with personally preparing the dishes and doesn’t pay attention to the restaurant’s maintenance and the functions associated with business development. Due to some basic business negligence, Di Fara’s has been closed a number of times due to unsanitary conditions11, and the restaurant’s appearance doesn’t meet modern expectations.

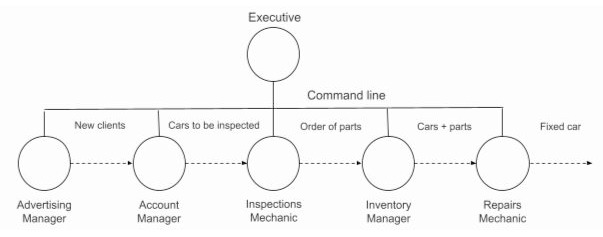

Imagine that open an auto service center. You have several skilled friends, and they’re each skilled at auto repairs. Until you divide the functions of running an auto shop in a way that one of them is responsible for working with clients, the other repairs powertrains, the third fixes electrical equipment, and the fourth is doing body work, there is no organization. If the functions are not distributed, it is impossible to organize the motion of the different particles: clients, jobs, repairs, car parts, money, etc.

Any organization is a flow of particles, which go from one function to another. As a result, this allows you to create the VFP of the whole company and, of course, accomplish a successful exchange with customers. When these functions are precisely defined, an executive can view the entire production of the VFP as a sequence of steps. For example, in any company there is a person responsible for advertising and attracting customers — they can be part time, full time, or independent contractors. There is someone who takes calls and greets clients. There is someone who performs initial inspections. A person who is in charge of supplies, orders the necessary parts, and ensures their delivery. A mechanic performs the repairs and delivers completed jobs to the client. If all these actions are performed, this produces the company’s VFP and then its exchanged with the client. With functions distributed relation to the VFP, it becomes possible to observe the motion of particles in the production flow, regardless of how small the organization is.

This simple chart points out something interesting in the management process. Any function in this organization, when not done, can completely stop the entire flow of production. A receptionist who greets visitors could just leave the front desk and not take any phone calls. In this case, all the efforts of promotions will be in vain and the production flow will be stopped. The person who makes the initial auto inspection could botch it completely and everybody will be out of a job. Moreover, the overall performance of an organization will not depend on the most productive employee but, unfortunately, on the most unproductive. This seems very unfair, but it confirms that an organization can only achieve success when all functions work well. A highly skilled professional may wind up without results or work if someone in the flow of product production doesn’t their job. Here’s the second observation: if the executive doesn’t catch the bottleneck in the flow of production, he will likely make mistakes that will reduce the company’s profits. If the bottleneck, for instance, is the person in charge of ordering spare parts, then the personnel in sales and promotion will have their tasks hindered, and company expenses will only increase.

One of the most common reasons for the lack of expansion is when the executive incorrectly determines the function that needs to expand, and then he spends time and money on it. While efforts end up increasing, profits decline. The executive, demoralized, might give up on expansion, and comes up with a strange excuses, “For our industry, it’s sufficient to have only X number of people in our company. “There’s actually nothing wrong with him, except that: he does not see his company as a sequence of functions and does not understand where the weakness lie.

The earlier example of the sequence of functions in an auto shop is simplified as it does not reflect: accounting, legal, etc. The executive is responsible for the entire VFP of the company; therefore, any function that is not assigned to an employee will be turned over to the executive. Here is what L. Ron Hubbard wrote in his article12 on this topic:

“Any major function, action or post left off an org board will wrap itself around the in-charge like a hidden menace.”

This is the primary cause of executive overload. It explains why managing a small company with few employees is far more complicated than managing a larger company. In a small company, the executive has to take on dozens of various functions, which creates an overload. I was only able to feel like a real executive when there were over 100 people working in my company. When various functions are performed by separate individuals, it becomes possible to plan, monitor, and identify bottlenecks in the production of the company’s VFP. It is very difficult to manage people who combine many functions, hire, train, and evaluate their work. Additionally, the performance of a person carrying out a multitude of functions is lower than that of a specialist. This answers the question of why small companies actually produce much less profit per employee and are incomparably harder to manage. A small business requires the mastery of management tools in order to overcome these basic barriers and grow into a big company. From time to time, I hear from entrepreneurs that a small business has the advantage of flexibility. However, that flexibility is not worth the how much effort is required to manage a small company effectively.

All activities in an organization can be divided into “technical” or “administrative”. Technical functions are those associated directly with producing the VFP that is exchanged with our clients. In trade, this is: working with suppliers, purchasing, logistics, order fulfillment, and delivery to customers. In manufacturing, it is the planning and assurance that all materials necessary for production are present, and the actual production. In a law firm, this translates to: advising clients, drafting documents, and representing clients’ interests in court and negotiations.

To understand which functions in your company are technical, you need to designate those that directly relate to the production of your company’s VFP. In the following chapters, it will be discussed in detail.

Administrative functions are those that provide the technical functions with good management, legal protection, personnel, finances, promotion and many other things. You could say that these are the functions that don’t produce the main product, but are needed for the functions that do. During the initial stages of business growth and development, executives mainly focus on technical functions. As the company grows, they discover that it is the administrative functions that become the bottleneck.

Interestingly, the technical functions are easier to organize and manage as they create the least amount of problems for the executive. In a restaurant, the chef won’t stomp up to the manager to request that he finishes cooking instead of him, and a waiter won’t demand that the manager the explain menu items to a customer. In a trading company, the warehouse manager will not bring an incomplete order to the executive and request that he finishes the job. However, administrative functions can be passed around quite easily, and passing the workload on to the executive is rather common. HR will demand that the executive makes all final hiring decisions; accounting asks for the executive to prioritize which bills to pay first. Generally, specialists for technical functions understand their VFP better with a greater mastery of the technology required to achieve it. Experience has illustrated that administrative functions create the worst bottlenecks in small businesses, and hinder the company’s development. Therefore, the better part of this book focuses on correctly managing administrative functions.

In any growing company, that is still relatively small and can’t afford to have a worker for each important function, employees will have to perform multiple functions. To prevent a problem from having employees carry out multiple functions, the executive must ensure precise understanding of each function assigned. As company expansion continues, the executive will surely need to re-distribute these functions. This brings up another another issue with smaller companies: administrative duties performed by employees change with the company’s expansion. Evolution of the company necessitates having an accurate idea of all the vital functions from the outset. The list will ensure that tasks are re-assigned intelligently and in a timely manner. To get an idea of what a functions list could look like, at the end of this book there are several examples of organizing boards for small companies. They may seem a bit bulky or redundant for a small business. However, these boards don’t have a single extraneous function. Each one of them is important to the company’s success.

When an executive or an employee of a small company sees such a chart for the first time, this question tends to come up, “Where can we even find that many people? And how are we going to pay them?” Remember that an organizing board is simply a compiled and organized list of functions. The functions get distributed among the existing employees. Conscious distribution of responsibilities allows the executive to see where it is necessary to expand the company. However, it’s not an instant process, it is always a sequence of steps. You cannot simply draw up an organizing board for a new business and immediately fill it with people. Different functions will have a different workload, depending on the type of business and its stage of development. Naturally, the ratio between the number of technical and administrative employees will vary significantly in different types of businesses.

For example, in a construction company you can have 300 technical employees working directly on a site while it’s sufficient to only have 30 administrative employees. But for a store that sells car parts, there could be just two people dealing with the technical functions, which would be working with suppliers and the delivery of merchandise. For the administrative functions, such as working with customers, there could be ten employees. Only through the process of business expansion is it possible to gain an understanding of the optimum distribution of functions among employees.

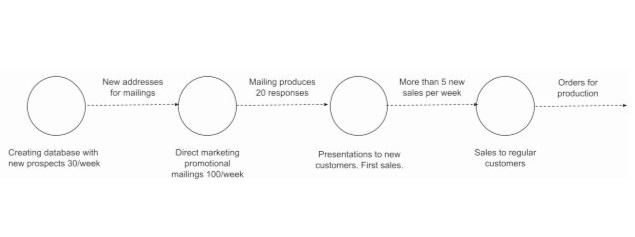

Let’s take a look at a chart for a company that produces various types booklets and magazines. Notice the distribution of functions in the process of getting orders.

For an average-sized printing company to hit a maximum quota, it has to generate about a hundred orders per week. This means that on a weekly basis, their Sales Department (about 5 people) needs to make an adequate number of sales and send them over for production. On average, a corporate customer will place about a dozen orders per year. If it takes a salesperson about a week of work to close an order, then each of them should actively be working with about a hundred customers. For a well-organized Sales Department, this is quite possible. However, not all existing customers will place new orders: some will switch to competitors while others have finished all their printing needs. If regular customers lost a year makes up 50% of the customer base, it needs to be compensated for by the influx of new customers. This means that each salesperson needs to obtain at least 50 new customers per year to become the new regulars. And for the entire Sales Department that means 250 new customers, which is at least five per week.

Have you ever tried managing the Sales Department where each salesperson, while maintaining relationships with hundreds of regular clients, also had to generate new clients on a weekly basis? I’ve organized sales in the past, and I’ve noticed that without having a manager constantly monitoring the area, a salesperson will generally work on closing existing clients, rather than spending time on those who will not necessarily place an order. In the early stages, it is necessary to do several sale presentations, meet with the client, and place several phone calls before closing the first order. But if this function is not monitored, the sales numbers will resemble a roller coaster. A salesperson, having exhausted his reserves of existing customers, falls into a sales-less rut, and frantically starts looking for new customers. Sometime later, he reaches a sales peak, only to fall back into the rut.

To bring in five new customers (who will become your new regulars) on a weekly basis, you’ll need at least twenty prospects in your pipeline, and you will have to work on them for some time before they turn to loyal customers. Marketing will have to provide the appropriate number of new responses to meet these demands. If this printing company promotes by mailing brochures, letters, and flyers, then in order to obtain the target number of responses, one should send out at least 20X that number of promotional material. In this example, it is 400 letters every week. This is its own function and it takes time to do it, as one needs to continually expand the prospect database. What happens if one neglects this function? The Sales Department’s job will become extremely difficult. The salespeople will have to manually find new clients through their connections and cold calling, while still servicing existing customers. If you ever tried cold calling to find new clients, you know it’s a thankless job. Thus, leaving a vacancy for the direct marketing13 function will result in sales becoming extremely difficult. Sales will require personnel with great patience and nerves of steel as efficiency will be too low. Additionally, if work becomes too difficult, you will have to pay dearly for it, plus it’s not easy to find people to do it.

Now, to get back to the subject of direct marketing. To fulfill a high volume of outgoing mailings, someone has to constantly expand the prospect database. To be able to send out that many messages, you need a database with more than 5,000 names. But even this database gradually loses its effectiveness, approximately 30% per year — address changes, changes in customer needs, and avoiding over-saturating the same list with the advertisements. To maintain the database in working condition, at least 30 names need to be added to it weekly. This is another function which you need to monitor all the time. Otherwise the effectiveness of mailings will be constantly going down while the cost of promotion continues to rise. There are numerous methods to expand such a database, such as from manually collecting the addresses from directories or online clients registering through a landing page.