Бесплатный фрагмент - Suvorov & business. Timeless Lessons from the Russian Master Strategist

First published in 2018.

All rights reserved. No part of the electronic version of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including posting on the internet and in corporate networks, for private and public use without the written permission of the copyright owner.

Here lies the wisdom of centuries old,

Here flows the firmness of valiant hearts,

Here saves, with deep devotion, father

All that he wishes for his son!

Alexander Suvorov

PART ONE. ACT OUTSIDE THE BOX!

Preface

Alexander Suvorov, Russian military general, is known to have spoken seven languages, including Turkish and Finnish. He was an expert in military history, a brilliant mathematician, and never lost a single battle.

The wisdom of this distinguished strategist and tactician of military art finds practical applications in any business. Suvorov’s strategy is the key to success.

Some of the famous general’s ideas will be considered in this book through the prism of the business environment. I hope that entrepreneurs will appreciate the parallels drawn and will learn many useful lessons from Suvorov’s covenants.

— Yury Yavorsky

Alexander Suvorov:

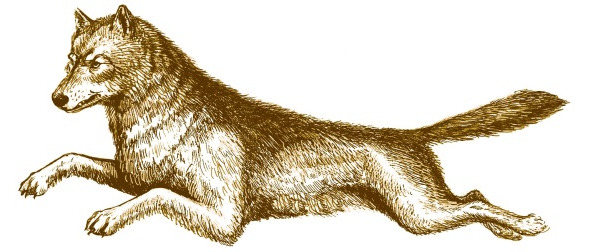

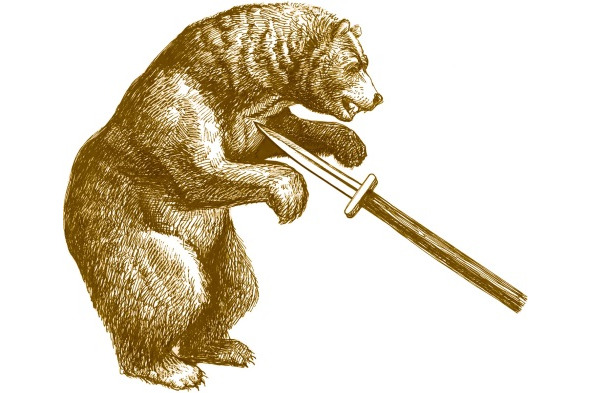

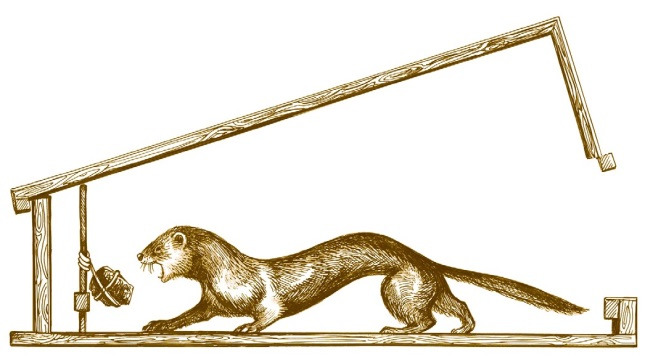

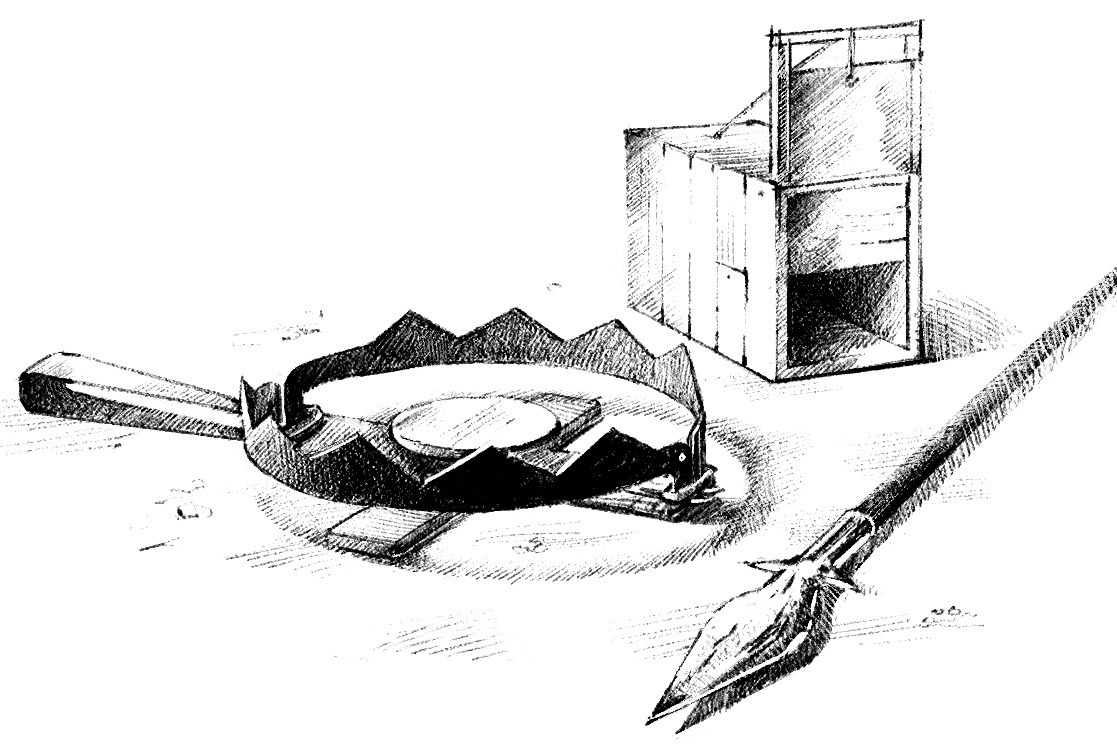

In none of your actions whatsoever shall you plainly reveal your ambitions:

— charge at a bear with a heavy hunting spear

— never flush out a wolf without back-up

— where determined to prevail by expending minimal resources, set a baited snare or arrange a trap

Here is my take on these instructions: an entrepreneur should be very particular about disguising their plans and the tactical scheme of future business moves aimed at conquering the market. Also required is a clear perspective on the size, capabilities, and behavior of adversaries. A completely different course of action is necessary for each of your competitors: some you would charge head on with a spear; with others you would choose to elegantly outmaneuver them.

Over my twenty-five years in business, there have been many cases in which I had to deploy a whole range of methods when bringing a new product or service on the market.

I have learned for a fact that the ways of an entrepreneur should be akin to the ways of a hunter who is out in the dark in the vast expanse of a wood or mountains. He never knows what the “beast” competitor has been plotting,

or what surprises lie there in the “thicket” of the market, or whether the vision of the “hunting” entrepreneur will “feed” him, his family, and his team, or whether he will be able to get enough “meat” to last him until the next fortunate “bag of game”.

…In the 1990s, my company manufactured dashboards for passenger vehicles. Browsing car spares at a marketplace, I stumbled on a seller who had assembled dashboards complete with a full set of instruments on offer, including the wiring for all requisite connections to other car parts. Then I wondered how many elements a dashboard contained. The answer was just over a hundred. The next step was to get quotes for all those component parts individually. (That was a time when vendors sold spares in the open, literally in a field, laying out their merchandise straight on the ground or on small tables; quite similar to what one sees at flea markets today). When I added up all the prices, the grand total came to 400 rubles – no higher – whereas a complete dashboard sold for 800 rubles. I procured all the components, assembled a dashboard at home, and sold it having doubled my capital. It would appear to be the ultimate success story. However, I came to realize that everybody was doing just the same: that marketplace had four other crews. So I decided to use the principles of supply chain management and barter economy, or take a “holistic approach”, as they might call it today.

I found out that dashboard clocks were supplied from Minsk (1,300 km away), speed meters came from Vladimir (200 km away), and so on. In short, all the components had to be shipped from other cities. There was no local production in Nizhny Novgorod. Having asked around at various factories, I saw I could “trim the fat” off the dashboard cost down to 200 rubles. Then, at the marketplace, I offered vendors who carried speedometers to swap two for one clock; I got those clocks by going to Minsk myself. I arranged with other sellers to exchange plastic parts that I bought in a town near Nizhny Novgorod for rubber parts, which some sold by weight, not by piece. My partners were able to expand their product range with no additional investment, and I was able to drive the dashboard cost down.

Trap with a decoy

At a cost of 100 rubles, I started selling the dashboards for 400 rubles at new sales outlets that bore no relation to me at all.

This made all four of my competitors cease assembly operations. I understood that they would need two to three months to regroup and resume dashboard production. I decided to go with the four-hundred-ruble offer for a bit longer, and simultaneously limit supply to one or two units a day, forcing sellers to take pre-orders and create lines — what people today might call “generating deferred demand”. After a month, I started raising the price by 100 rubles every week. Even with a 1,200-ruble quote, I was getting a few months’ worth of pre-orders.

My competitors never saw what was coming though. They were simply happy that dashboards were selling for RUB 1,200, resumed their make-shift assembly operations, and set similar prices. Today these recollections cannot but make me smile. After a while, I played out the very same formula again, and the competition allowed me, again, to establish a temporary monopoly for a couple of months. The profits that an entrepreneur makes within this short period can be several times higher than regular profits for one or even two years.

I am always in control of production costs at my workshops. This applies to each and every item, be it a small component, like a run-flat tire insert that we sell to a partner, or a finished vehicle. And I always try to work out the costs of my potential rivals.

I once got involved in a tender with a competitor. At that time, my company already had its own production facilities and manufactured thousands of components and parts; our competitor, on the other hand, was basically buying components from suppliers.

It was quite easy to calculate that his cars, which would be competing against our vehicles, cost RUB 2.8 million each to produce. Unfortunately, the bids in that tender were not evaluated on product quality, brand history, or prior successful contracts. It was all about the price. And it all came down to two principal objectives: not to sell below our usual price, or we would have to stick to that price going forward; but also to outsmart the competitor. I had to begrudgingly lower the bar and strip the vehicle of one-of-the-kind, patented options that only our company could offer. That made it possible to bring the cost all the way down to RUB 2.1 million.

The tender opened at RUB 3.8 million, the price gradually slipping down and sometimes stalling, so far as was reasonable for internet bidding. Our bids were lightning fast to show that we did not hesitate to drop the price; our competitor was faltering, each new bid taking longer. The longest halt came at RUB 3.1 million. We bid down once again and at RUB 2.9 million, the tender was ours.

During another tender, for low-margin cash-in-transit (CIT) vans I was able to do exactly the opposite. It was clear that the two other participants would fight to the bitter end; after all, the prize was an order for CIT vehicles for a major Russian bank. A contract like this can easily mean full production capacity for 5–6 months even for a heavyweight.

In my operation, however, I have always valued profit margins over production output. To digress for a moment, I see that many start a business with a totally inexplicable vision in mind. For example, one of my competitors ran a company with profits lower than his employees’ pay and firmly maintained that the ultimate goal of business was to provide jobs and that he would never sack anybody. His business run was short: he had to dismiss everybody and leave the market.

Back to the tender now, we did apply along with the others. I knew my production costs to the penny and had a rough idea of my competitors’ costs. Our companies differed in size. I employed three times as many staff, relied on own production, had laser cutting systems and CNC machines. We manufactured thousands of components in-house. The competitors preferred to buy from various suppliers, which chipped away at potential profits and added to costs. With an average CIT van going for RUB 700,000–800,000, their production costs stood at RUB 550,000. Our cost was just under RUB 460,000.

The tender opened at RUB 770,000 and quickly reached RUB 670,000. We were silently biding our time. The downward trend started to slow down and halted at RUB 580,000. This would seem to be as low as it would go… We bid at RUB 570,000. Time passed. I was getting anxious: had I miscalculated? The thing was I did not want that contract.

The tender was seconds from closing when a RUB 560,000 bid came in and I was off the hook — it worked! I was able to ensnare a competitor into a low-margin contract that would not be profitable and, most importantly, close him off the market. This was a long-term victory.

But that was not the end of the story. The winning bidder pleaded with the bank to top up the price by at least 10%. Failing to get that, he turned to his competitor asking for help to make good on the contract. The bank agreed to have two suppliers. At the end of the day, my two competitors first wrestled, plummeting the price to barely top the cost, and then ended up together in the low-margin segment where they ran down their production facilities and wasted time. And I used that time to conquer the VIP segment.

To this day, RIDA-branded vehicles from Russia are known for their quality build and protection on a par with global big-league brands, such as GARD in Germany or CARAT in Belgium; RIDA cars sell in dozens of countries in the Middle East, Asia, Europe, and Africa.

SMART CALCULATION PAVES WAY TO VICTORY

Alexander Suvorov:

In offensive action, always rely on concerted efforts and swiftly attack the core forces of the adversary; with that, however, never fail to throw into disarray enemy troops that threaten your flank or rear guards.

Operating in a constantly changing competitive environment, it is vital to remember that business is akin to battle in some ways; it is a struggle for the market and clients. Once you are determined to act, there is no place for half-measures or doubt. Action must be swift and you must be fully engaged 24/7.

At the same time, you need to maintain a 360-outlook and proactively analyze changes in your competitors’ behavior, prices for their goods and services, and compare these changes against your target market.

Suvorov’s strategy is pertinent to virtually any area of activity or entrepreneurial decision-making. Suvorov commanded rank-and-file soldiers, officers, and generals. His campaigns and battles reveal the great managerial proficiency of a leader who made no exceptions applying his rules and principles with strictness and fatherlike justice.

There are accounts of one march rest during which Suvorov dared a soldier to see who could eat a serving of porridge faster. Excited and humbled by such an honor, although he was no raw recruit as military service was twenty-five years back then, the soldier started shoving in the hot porridge, encouraged by fellow troops. Suvorov took his time, scraping the porridge from around the bowl’s brim where it cools the fastest.

Waterfall uproots rock

The soldier started choking on scorching mush with a third of the bowl to go, whereas Suvorov was already finishing the last spoonful with a shrewd smile on his face. He was not tall — the soldier towered two heads above him and was twice as broad — but wisdom and strategy prevailed.

Suvorov’s incredible feat of crossing the Alps is known to many Russians from history textbooks and illustrations. For one, Suvorov was able to mount an offensive from behind enemy lines, and he also managed to come out victorious with limited resources, surrounded by enemy forces and greatly outnumbered. He lost 700 men. The French lost up to 6,000 and 1,200 of their troops surrendered. On that Swiss campaign, Suvorov ordered to stock up on rations in nearby villages for a number of troops that greatly exceeded his army. Naturally, the French found out. Over the three days that they were holding council, reinforcements arrived at Suvorov’s location and the generalissimo had had time to arrange the disposition of forces, have each unit perfect their maneuvers, and drum up high morale, so that eventually the Russian troops’ fierce attack threw the enemy into panic. A clever ruse and smart calculation paved the way for that victory. Nevertheless, Suvorov was never formulaic and always employed new tactics.

A Moscow entrepreneur running a small retail shop decided to procure shoes directly from the Italian manufacturer. She went to Italy herself and found that designer shoes by high-street brands had a discount subsegment. These shoes sold cheaper due to minor production flaws or as older collections. The price tag was several times lower and topped out at 10–15 euro.

Other than for harvest, why ramble the fields with a scythe?

Flanking: isolate, cut, stack. Envelopment: seize, shear

She bought a hefty batch of shoes, put it on display, and waited for a swarm of customers or lively trade at the very least. But… Sales dropped two or three times below average. A friend of mine, who told me this story, came by to visit the entrepreneur soon after. He found her in tears, on the brink of selling the shop and her business.

He gave her two tips. The first was to “throw in another zero on the price.” The shelves and inventory were swept clean within a month or two! The business lady went to Italy again and bought another similar batch. She tried to sell it at ten times the cost again, but on the second go, she did actually go broke. All because she did not hear or just did not want to heed the second tip. “Once you are sold out, never do this again!”

It is possible to trick demand once or mislead the competition for a limited time, but you have to remember: in their ability to survive, evaluate and see through lies, consumers and the market are extremely sensitive to change and will not be taken for a ride twice.

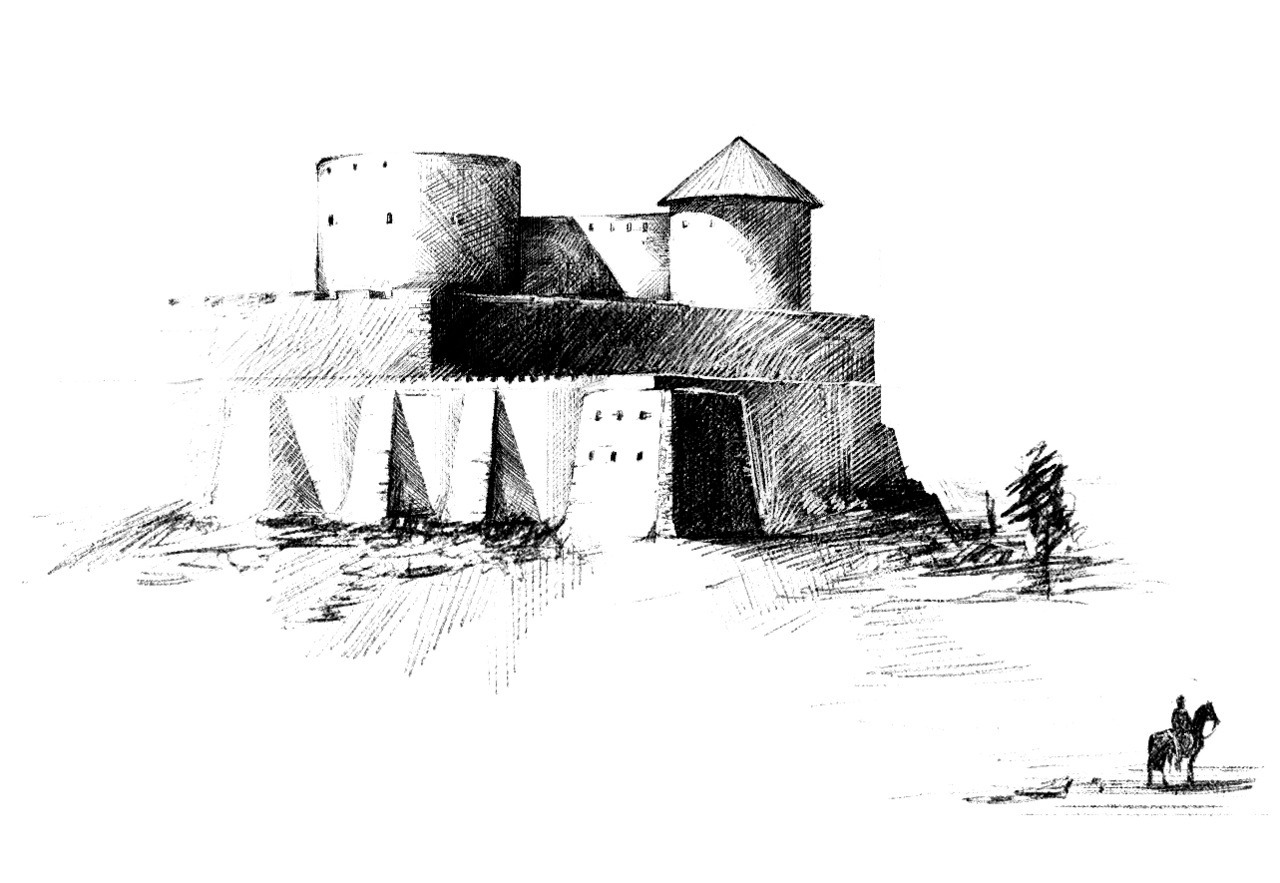

As a source of insight for business strategy, one can discover tremendous value in the story of Suvorov’s assault and seizure of Izmail. It was thought to be an unassailable fortress. Suvorov, a general-in-chief at the time, began by assuming a disguise so as not to be recognized. Wearing shabby attire, riding an old nag, and, accompanied by a single orderly, he studied the fortress in detail.

Next, he ordered to mock up fortifications that closely resembled Izmail for drills. His troops, shoulder to shoulder, practiced blanketing the moat with bundles of branches, to prop up ladders and quickly scale the walls where they practiced stabbing and slashing dummies. The Turkish and Russian forces were more or less equally matched; the fortress fell two and a half hours into the battle. The Russian Army lost 2,000 men; the Turkish Army lost 26,000, with 9,000 captured.

Any business venture can be approached as an unassailable fortress. Before Suvorov, Izmail had been besieged and stormed by three generals, including Prince Potemkin. What failed them? They had the same troops, the same weaponry, and there was the same fortress…

But did they reconnoiter the fortress looking for weaknesses? Or did they drill their troops on similar fortifications? At what time and in what manner did they launch their offensive?

Suvorov first undertook a thorough and forceful two-day cannonade; the attack started at 5:30 am, when the Turks were at morning prayer. And he won.

When an entrepreneur makes preparations to launch a business project, similar strategic thinking and action are indispensable.

As I realized that retrofitting the latest-series cars required glass of a whole new level, I decided that we could not use existing technologies. Increasing the thickness of glass by a mere millimeter made the car heavier by 50–100 kilograms, which degraded its performance and put additional load on its strained drivetrain.

Under various “monikers”, sometimes posing as a prospective buyer, sometimes a supplier, and so forth, I visited production facilities in different countries, such as Italy to Brazil. I always studied the production process, the equipment and other details of these complex operations very carefully.

I retraced Suvorov’s footsteps and carried out exhaustive reconnaissance first. I made an estimate of the resources needed to set up my own production, got an idea of the breakeven time, considering that I had already been running a business of building custom cars. Not only that, but I also made a couple of sample purchases of glass from my competitors and conducted my own delamination strength tests: separation of layers at extreme temperatures from – 50 to +50°C, plus transparency tests, assessed fabrication precision, and so on.

Scouting for staff was no use, as Nizhny Novgorod, a city of one and a half million, had no such specialists at that time. For specialty glass, there were no trained process engineers, no specialized chemists, and no line workers with relevant experience. So I assembled a dozen enthusiasts and idealists comprised of engineers, chemists, mechanics, and servicemen, and we started experimenting and learning as we went.

We expended hundreds of square meters of glass of different configurations, different interlayers, and autoclaved them at different temperatures and pressures.

It took three years to create a working team, buy the equipment, and build a designated building. In 2007, we started producing our own state-of-the-art car glass. Since then, RIDA vehicles have met the highest world standards. Our glass has been tested in Russian and German testing labs.

In line with Suvorov’s covenants, I focused on the main goal: conquering the market with a new product, crushing small formations of competitors in the process and forcing out of the market those who had had a competitive edge over my company, either in price or quality. The RIDA brand became the leader in Russia, by the quality and quantity of VIP cars bearing marques such as Mercedes, Toyota, Lexus, and many others.

LESSONS FROM THE DRAWINGS

Alexander Suvorov:

Bundle your broom as you go: individual bristles are brittle — a broom knocks down a man. Do not set up any designated supply channels for the rear.

Broom case

What lesson does Suvorov teach a businessman when he speaks of bristles and brooms?

Clearly, in any business endeavor, in any business campaign, when you start out on your own, you are as brittle as a bristle. If an entrepreneur takes all the decisions alone, without the support of the company, his trusted staff, if an entrepreneur organizes no brain storming and never taps into the brainpower of the team, then one day he is doomed to snap. Even worse, he is focused on realizing his business plans and ideas and not capable of “sweeping action”; that is, managing the torrent of minor and current tasks that inevitably pile up due to the breakneck pace of business. Teams should only be built on the go; in a similar fashion to bundling a broom, making it strong and not brittle, sometimes even replacing worn bristles.

— A broom sweeps in front, picks some up at the sides, and drags from behind.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.