Бесплатный фрагмент - Small business. Big game

INTRODUCTION

This book is not about how to come up with a brilliant business idea, but about how to organize the work of a company so that its employees function as a genuine team and are capable of implementing a worthwhile idea. Experience shows that the brilliance of an idea is undoubtedly a plus, but if you look around carefully, you will find that most flourishing companies are not actually based on any revolutionary idea. What is revolutionary about McDonald’s fast food, Starbucks coffeehouses, or products sold by the majority of chain supermarkets? Every business has its own expertise, of course, but the most successful companies offer their clients fairly ordinary products. Why then, of hundreds of competing fast-food chains, have only a few achieved great success, and of hundreds of grocery stores, why have only a few grown into large chains? In most cases, the secret is not in some special know-how or secret formula; it is in how a company is run.

It’s been twenty years now since my friends and I opened our first company. We were extraordinarily enthusiastic about having our own business and felt like travelers setting out in search of adventure. We all were in our early twenties, recently graduated from a higher education military institution, and knowledgeable about computer technology. The computer industry was just beginning to take shape, and it seemed to us at the time that our knowledge and skills were all we needed to create a successful business. Of course, we were apprehensive about the obstacles we faced, but the prospects were alluring. We had no money to buy ourselves equipment to show to clients, to create a minimum inventory, or to fulfill the other requirements of an official Apple dealer in Ukraine. We therefore decided to begin by selling users and official dealers all sorts of auxiliary devices such as external hard drives, scanners, and software.

We decided to deliver to order: We simply took orders, accepted prepayment, and then supplied whatever was needed. There was no talk at all of any sort of serious planning; we simply grabbed any order on which it was possible to turn a profit. No matter what the client wanted — instructional programs for preschool children, a professional scanner for a publishing house, a portable printer or a batch of modem cables — we took on the order. We very quickly earned the reputation of being fellows who could get anything for Macintosh computers. We found a suitable supplier in the United States — a small computer firm that bought everything we needed from various manufacturers and shipped it to us. Then we would deliver these goods to our customers. Our own equipment, meanwhile, consisted of nothing but a single computer on its last legs (good only for printing documents), a fax machine, and an electric kettle. A company that procured equipment used by oil refineries gave us a room in its office.

After several months of working by the maxim «We get what you need,» we already had good connections with authorized dealers, and thanks to this, we were able to land our first big fish. Even before we were an authorized Apple dealer, we purchased a shipment of computers from a dealer — a shipment that the customer had for some reason refused to pay for — and we sold that lot to another official dealer. Payment for these computers went from Switzerland to Turkey for some reason, in exchange for Hilal chocolates. Our profit from this transaction consisted of two computers, which became our primary asset and served us for many years to come.

After a while, we became an authorized dealer, and this enabled us to obtain new clients, which at the time were mainly western companies and organizations that had opened offices in Kiev. They were importing a significant portion of their computer equipment from abroad. The computers were mostly old and arrived the worse for wear, and they needed servicing and repair, so we earned a lot by providing such maintenance. Laser printers back then were very expensive and frequently broke down, and spare parts for them were expensive, too. So I simply went to a worker I knew at one of the Kiev metalworking plants and ordered a bag of spare printer gear wheels from him for twenty dollars, which enabled us to repair laser printers at a staggering profit. Electronics specialists whom I knew would repair computer power sources, which saved us from waiting a month for deliveries of spare parts and enabled us to solve a client’s problem quickly and earn something in the process.

Within a year is we rented separate premises in the city center and opened our own office. We had no money for redecorating, to be sure, so my partners and I refurbished the place ourselves, and we were able to buy office furniture for a song from a failed business. There was no money for an alarm system or guards for the office, either, and for several months my partners and I took turns spending the night in the office, doing guard duty. Business proceeded, and after a while, we began to earn good money on deliveries of desktop publishing systems, video processing, and computer animation. We were incredibly excited by our success, our profits were growing, the company gradually began to expand, and our first employees were hired. In our very first year as an Apple authorized reseller, we were first in the country for quantities of equipment supplied. That moment was the peak of our enthusiasm for the future of the company. But even then the first signs of impending problems began to appear.

From the first day of the company’s operations, my partners put me in charge of management, but I had no idea what it meant to run a company. It seemed to me that it took just a few things: agreement among partners and employees, personal competence, and personal example. But when we hired our first employees, I found that it was also necessary to allocate areas of responsibility, plan the work, and demand high quality performance.

Until then, the company had been essentially a sort of club, where everyone chose his favorite area of activity and pursued self-fulfillment in that area. And that was great! After all, if a person chooses his own area of activity, he usually acts it with the utmost responsibility. Look at how hard a person can work tending his own garden or engaging in his favorite hobby. It does not even occur to him that he may have worked too much or been paid too little for this work. When a person freely chooses the work that he is going to do, he feels really good about it and does his best. If he is forced to do something that he finds useless and unnecessary and does it under duress, he will, at the very least, be unhappy with the work. His productivity will also be very low; there is a good reason why they say that the lowest labor productivity was in slave-owning societies and prisons. Wise parents know that if they force a child to wash the dishes, that child will come to hate washing dishes more and more with each passing day and will, at best, grow up and hire himself a maid, and is at worst — is will spend his whole life with mountains of dirty dishes piled up in the kitchen. To get him a child to wash dishes on his own initiative, it is necessary first and foremost to inculcate a desire on his part to do so, to make an interesting game of it, and then the dishes will be clean and the child content, as well.

Managers often forget that a company’s most valuable asset is the creativity of its employees and their earnest desire to work. It must be noted that is actually not so much that managers forget to motivate workers to be productive; they just don’t know how to do it. Areas of responsibility need to be clearly defined, after all, and not only the dream jobs must be allocated but unpopular work, as well. So it was that in my first computer company I came up against the need both to clearly allocate functions and, strange as it may be, to require positive results from employees and partners alike. At the same time, I had no precise idea whatever of what the subdivisions and the functions should be, and therefore, in attempting to bring order to this work, I encountered many problems. And when I tried to manage the work of my partners, I came up against the idea of universal equality, which thwarted my attempts to impose order on their work. To some extent, I felt like a ceremonial VIP — formally acknowledged as chief executive but effectively without the power to insist on achieving positive results, since we were all equal partners.

By this time, the company was already three years old, we began to contend with tough competitors, and customers were becoming more demanding. In order to keep up and to develop, we needed more than just knowledge of computer technology and the desire to work. As in any other area of activity, increased competition led to decreased profitability. The standard markup when selling Apple computers was 32 percent when we began our work but fell to one quarter of that over these years. Of course, demand also grew during this time, and gradually this technology went from something exotic to a popular tool for desktop publishing. But in order to develop in this market, we needed real organization and effectiveness. We had no precise division of labor, and no system for planning and monitoring the execution of plans, and therefore we were unable to take advantage of the opportunities presented by growing demand, but we were nevertheless well aware of all the problems that came from the growth of competition.

At that moment, I became fully aware of my inadequacy as a manager, so I stopped enjoying my work to the extent I had when I was working directly with computers. Attempts to take control and manage the company’s performance and productivity only led to quarrels with my partners, which in turn impeded the management of employees. Operating efficiency was too low, and we were not only losing control of the company’s position in the market but also losing clients, although usually our bids won out and led to profitable contracts, allowing us to keep our heads above water. But I understood that unless we changed our methods of managing the company, our days were numbered.

The only problem I saw then was the differences of opinion with my partners, whose own ambitions, it seemed to me, kept them from allowing me to be an effective CEO.

If a person is incompetent, he cannot grasp what is actually the source of his problems. He therefore focuses his attention on some contrived reason for a specific problem, which of course does not help to solve the problem. This is how an unskilled computer user behaves when, in attempting to deal with errors, he completely reformats the hard drive and reinstalls the operating system. He does this over and over, but if the real reason for the computer errors is an overheated processor or memory failures, this will not solve the problem. Thus I, too, thought at the time that the only way to deal with the company’s problem was to reformat existing relationships. In the end, I did indeed reformat them, but not with the desired result. There were three partners, and I, finding myself in the minority, had to leave the company.

This sort of approach is common in small business that if something does not work out, an employee can change jobs, or the owner can open a new company, but as a rule, in this new endeavor he will sooner or later encounter the same problem again. I know many people who own several small businesses that are as alike as two drops of water in terms of their problems. This failure to change is tantamount to repeating third grade over and over again simply because the homework is too difficult in fourth grade–many actions are taken, but the result is poor.

After leaving that first company, I came to two conclusions. The first was that authority must be in the hands of one person, and the second was that there should be no co-owners at all. The first was true, but not the second. The problem was not in the number of co-owners, but in how I had managed the company and dealt with my partners. Fortunately, I stopped making such mistakes after that, and I was therefore able to create two successful manufacturing companies and one consulting company. But I did not immediately recognize the reasons for my first setback, and I had to seriously look into how to manage a group of people and organize their work.

The story of my first business is not unique. Many small companies are created based on the enthusiasm of a few people, grow to a certain size, and then at some point cease their development. But as is well known, that which is not developing is dying either quickly or slowly. Very often the great ideas of a company’s founders begin to be put into practice quickly and yield good results, and the business grows to a certain size, but then the company gradually withers and dies.

A friend of mine manufactures first-rate leather book bindings, and they are really very nice — wonderful leather, beautiful tooling, resulting in a very high-quality and aesthetically pleasing product. In my travels all around the world, I have seen many books in leather bindings, but I have not seen products of this quality in any other country. This enterprise is situated in Kiev, and about two dozen employees work there, most of them directly engaged in production. The company’s founder is a very intelligent, decent, and educated person. Employees work in that company for years at a time, and there is practically no turnover. The company pays a good wage, and relationships among employees there are quite relaxed and pleasant. It can be said with certainty that his business is a very stable small company. There is only one but here: His company has not grown for the last ten years.

When I spoke with him and asked him about his development plans, I saw that he wanted his products to be used by people throughout the world but that he was being held back by fear of the problems involved in expansion. He thought that the main thing keeping his company from developing was the threat of a reduction in quality and the difficulties associated with advertising and sales in new regions. Essentially he, like me in my first company, did not even see the true reason for the problems involved in expansion; he did not know how to organize the work or how to manage people, and what’s more, he was afraid to do so. Yes, he had a perfectly respectable income for a company of that size as well do satisfied customers. But despite being bogged down in the routine of operations, he himself worked with big customers, he himself managed financial affairs, ran production, and handled personnel. Such an array of duties would be hard to hand over even to his son, let alone a hired manager. No one would want to take on that whole headache. Looking at this situation honestly, the employees of this company had no prospect of advancement if the company did not grow. Therefore, even when a very talented and ambitious person joined the company as an employee, sooner or later that person left. Some company founders tell, with a mixture of pride and regret, that many of their former employees have started their own businesses. This is truly something to be sorry about. If these men and women have been able to found their own companies and have achieved some results, they could have made real contributions to their previous employers. It is obvious that a group of capable people can move mountains, but instead of a single company with tremendous results, the outcome is often several small and usually unsuccessful businesses.

The smaller a company, the less earning power it has. But what is interesting is that managers and employees of small companies have more problems than those of large companies. This is easy enough to understand. In a small company, most people are jacks-of-all-trades, performing a wide variety of functions. Thus quite often in a small trading company, a single employee takes orders from customers, works with suppliers, arranges deliveries, resolves conflicts, and collects receivables. A department head in a small company performs even more functions. It is therefore difficult to hire people to work in small companies, as a person must be prepared from the outset to perform a multitude of functions. Managing such employees in small businesses is even more difficult because when a manager requires one thing, an employee can always say that he is busy doing some other very important thing. It is also difficult to raise the level of professionalism of such people because there are too many different areas of activity, and it is even hard to know what training to send them to — computer courses or a seminar on advertising. It is hard to make an employee more productive when he or she has been doing too many different things; there has been no clear job definition for such an employer, so it is difficult to decide how to make that person more productive and focused through in-service training in computer courses or a seminar on advertising. And the most vexing thing of all is that, with all these difficulties, a small company does not bring in a large income, and this means that it cannot properly take care of its employees or make a substantial profit for its owners.

Take a look at the employees of successful small companies and you will find that they work long and hard, frequently more than the employees of big corporations. At the same time, they are paid less, and they have fewer opportunities for professional advancement and a more focused area of activity. Look at this from the point of view of a capable employee who wants to achieve much in life. What are his prospects in a small business? If he is very good, he will very quickly hit the ceiling. Even if he becomes the top manager in a small company, his problems will still outnumber his triumphs. At the same time, in attempting to achieve great results in his work, he will inevitably take on more and more related areas and accumulate duties, but for most of the time he will not be doing what he dreamed of, but simply coping with chaos. You could say that a small business has one thing going for it: It may grow into a big one.

In order for a company to continue growing for a long time, it must leap many hurdles, including people-management problems. As a consultant, I interact with a large number of managers and employees, and in small business, I often meet people who are not even aware of the rules of the game that they are playing or the laws of people management. Frequently, people who are simply good specialists become managers; they do their work capably but have no idea how to organize the work of their subordinates. Most of them think that a manager’s responsibilities are giving orders, establishing incentives, and imposing penalties. Even so, they don’t even know how to handle giving orders professionally, have no idea how to issue them correctly, how to monitor performance, or how to get informative and useful feedback. I am certain that you have dealt with these types of sales department managers, people who only recently were good salespeople, are competent in working with clients, but know nothing about what to do with their subordinates. Their favorite line is «Do as I do.» They naively think that the main duty of a sales department manager is to follow his superior’s example and advice regarding sales.

I was once such a manager, naively supposing that, since our company sold computers, the main thing was sales, and that all our success depended on that. I was quite a good salesman, and all the other employees of the company observed with pleasure how I did it. Of course, applause is gratifying to a person’s self-esteem, but it is impossible to create a successful company based on a principle of «the star and the rest»; for great achievements, teamwork is necessary.

Being a star is no simple matter, and creating a truly successful company and achieving great results using such an approach will not work. Real success calls for not only professional skill in sales or knowledge of production methods; the key factor is the ability to implement operations management. This is not an incredibly difficult thing, and the principles of managing a group of people are as old as the world. But it is also true that these principles are very difficult to apply in a small company in which every person and every cent counts. In this book, you will find answers to the fundamental questions about company management and, most important, how to apply this in practice, even in a small company.

Chapter 1

Team Play

The first thing one must do is to understand what administration is. Most people are firmly convinced that administration is something unrelated to work itself, something extraneous. Administration is frequently perceived as a synonym for bureaucracy — a waste of ink and paper that only complicates work and adds nothing of value. It imposes the burden of submitting reports, participating in planning meetings, and filling out standardized report forms and documents that measure and guide the productivity and overall activity of the company. It seems to employees as well as to managers that all these reports have been imposed for the sole purpose of impeding work. And instead of simply selling or producing, people are forced to waste time filling out forms as part of reporting to management. It is not surprising that administration has such a bad reputation, and that administrators seem like bureaucrats of a sort, people who are not interested in the real business of the organization and merely shuffle papers.

Often, when a management consultant — essentially an administration specialist — comes to a company, employees do not greet him with ovations. And when a company manager tries to set up a planning system or implement regular reporting, employees perceive this as an infringement on their freedom and a questioning of their competence and productivity, so they respond to such measures with hostility. Yet everyone, for some reason, forgets the simple truth — that for a game to exist, there must be certain rules.

Try to imagine a football game with no preplanned game schedule, no score charts, no system for counting points, no rules for the coin toss, or other administrative tools. Of course the game itself does not consist of these schedules or score charts, but what would happen if all of these administrative tools in football were suddenly to disappear? The world would lose a great sport.

In any business, a technical and an administrative component can be distinguished. For example, in the work of a salesperson, the technical aspect is how he interacts with the customer, demonstrates the advantages of the product, overcomes objections, and closes the deal. But even if that salesperson is working on his own, he still needs to engage in some sort of administration — at a minimum, accurately recording his clients’ names on a notepad and adding up the amount of goods he has sold. This is obviously necessary, and if he does not keep a daily count of his sales volume, he will be unable to understand what technical actions are improving his results. He will not even be able to assess whether his work is going well or poorly. If he does not keep notes on his work with customers, then in only one month he will not be able to recall the details of his work with each of them, which sooner or later will have an impact on his sales. The work of the factory or of the purchasing department depends on the work of the salesperson, and if he does not have a plan to monitor current sales accurately and estimate future sales volume, the factory workers or buyers will not be able to plan their work, either. If a person works in a team, administration becomes an important component of a business activity, since it makes it possible to coordinate the actions of each employee with the other members of the team.

It may be an unusual idea, but only through capable administration is it possible to create an interesting and inspiring game! This sounds like a paradox, since in the minds of many, administration is something terribly boring, whereas the exciting activity of a game is entirely different– something full of emotion and enjoyment. Administration is associated with formalities, a game represents freedom and drive. So let’s take a look at this sharp distinction.

People really like playing games, and even if there is no chance of participating in a game oneself, just watching a game can bring pleasure. Nothing can compare with the interest and emotion aroused by an NFL or college championship game; cities come to a standstill during a final game, and discussions of how «our guys» played become the main topic of conversation. Sports — the Olympics, major-league baseball, professional football, college football — all enjoy lucrative media coverage and draw huge audiences in the United States, while soccer has made remarkable inroads thanks to its popularity in schools, opening America to the worldwide excitement that the game generates.

Or consider video gamers who battle virtual monsters. They move their heroes around, devise tactics, and are prepared to spend all their time on this. It is so entertaining that it is simply impossible to drag them away from the computer, and what is amusing is that victories in a computer game bring them nothing in the real world. Yet they are frequently prepared to sacrifice their real lives for the sake of the adrenaline rush that they get during a game. The game consumes all their attention, and they spend all their time on it, frequently at the expense of their health. You have surely said to yourself at some point, If only he would put as much energy into his work! And it is true: The enthusiast not only can achieve unbelievable results but he also takes pleasure in the game itself.

You don’t really think, do you, that top athletes who set incredible records do so for the money or from a need to support their families? Of course, prizes are nice, and when prizes in a game liberate you from thinking of earning your daily bread and allow you to devote yourself fully to the game, that is wonderful. But people play games just because they enjoy playing, and they like to reach the mountaintop — to become champions in their field of activity. What can we do to turn work into a game and make it inspire as much emotion and passion as ordinary games do? First of all, to do this, we must understand how a game works.

First, participating in any game involves a personal choice. In order for a person to really and truly play a game, he must choose that area of activity himself, and he must have a desire to prove something, to achieve some goal. Try to make a man play football if he does not want to, or try to drag a person who hates team sports to the stadium. Remember those unfortunate ones whose parents sent them to law school even though they dreamed of pursuing art. In the best case, such people will waste several years at a higher-education institution before eventually taking up their favorite work. In the worst case, they will actually become lawyer’s against their will and will do that work with loathing for the rest of their lives, taking no pleasure from the work and, as a rule, achieving little of any importance.

It is difficult to create a masterpiece if you do not love the work that you do. This is probably why it is so difficult to manage soldiers who have ended up in the armed forces only because they couldn’t evade the draft. You see, these fellows, once in the armed forces, continue to actively struggle to avoid playing the armed forces «game», and to actively demonstrate that they have nothing whatsoever to do with it. Their favorite game in the armed forces is to compete among themselves to see who can do the least work and to count the days until they are honorably discharged. For them, being in the armed forces is not a game; it is more like being in prison. Then look at professional soldiers, who have chosen to play in this very demanding game. They seem to be made of different stuff, and most of them truly like this activity. In spite of the difficulties and danger, they are proud of their work. The only difference is that some play the game of their own free will, while others have ended up on the playing field by force of circumstances.

Look at how much easier it is for many people to get carried away in a game involving killing virtual characters on a computer screen than by earnestly pitching in and helping their company become a market leader. Although it is illogical, many people nevertheless may sincerely believe that the success of a company is not their business, while the illusory win in a computer game is worth the investment of their time, energy, and passion. The same type of person may earnestly root for his favorite football or baseball team and be utterly indifferent to the success of the company he works for. The reason for this is simple: For many people, the company where they work is not the place in which they seek to achieve something of worth.

How do you think the average employee of a company will answer the question, «What do you consider to be the goal of our company?» My experience says that in small business, you will very often hear this response: «Profit». This means that the employee considers increasing the owner’s wealth to be the meaning of the existence of the company in which he works. Naturally, in this case, there can be no talk of the attractiveness of the goal, of a desire to play the game to reach that goal, or of creativity. Why should he play the «let’s make the boss richer» game? Perhaps, of course, that employee receives some portion of the profit and is therefore interested in increasing it. But in that case, he is playing the «earn a bit more» game, and this is not team play. Managers are surprised that employees have little motivation to work productively when they are «playing the game» of work simply to enrich the owners and managers. But who wants to run around on the field after a ball for the sake of lining the boss’s pockets? If this is the case, it means the company’s goals do not inspire employees to share these goals, do not arouse passion, so essentially, these people are not players in the company’s game.

The most common reason for this is a company’s lack of worthwhile goals that team members would find attractive, or a lack of understanding of such goals. If a person does not understand the goals of an activity, there will be no game. He may of his own choice aspire to achieve the company’s goals only if he is aware of them and, of course, if his manager capably promotes these goals. Simply imagine a person who has been told to dig a pit but has not been told why this is necessary. Only a robot will put its all into such an activity. But explain to the same person that this pit is needed in order to supply hot water to an orphanage, and you will see how his attitude toward the work changes, and how enthusiasm and energy appear.

Setting goals for a group has to do with administration, not the technology of a company’s activity. Thus in football, the technology is the methods that players use on the field, of which they must have perfect mastery, whereas setting the goal «let’s kick our opponent’s ass» is administration. Without such a goal, even the most sophisticated technological methods lose their meaning.

The next integral component of a game is rules that establish the boundaries of the game and describe the possible actions. Without rules, there can be no game, and if the rules fail, the game collapses. If there were no precise rules in football and every player acted as he saw fit, the game would turn into chaos. A company must also have quite specific rules, which precisely define the rights and obligations of team members. Of course, all rules create restrictions that are necessary for the game to continue. Quite often, when rules such as a fixed work schedule, a dress code, or reporting standards are introduced in a small business, it leads to employee resentment.

There are two reasons for this. The first is clear enough; the introduction of a new rule, reasonable and useful as it may be, is a change to a preexisting rule, albeit an unwritten one. If a dress code is instituted, this means a change to a previously existing tacit rule that allowed employees to dress for work however they liked.

At one of my companies, a new policy1 was implemented that regulated the appearance of employees, the use of makeup by female employees, and the use of fragrance. Even after employees became familiar with this policy, considerable effort was required to achieve compliance with these requirements. These rules were reasonable and simple, and indeed no reasonable person would dispute that professional employee appearance inspires greater confidence in clients, whereas loud makeup or strong perfume undermine it. Nevertheless, managers had to apply considerable effort to get employees to comply with these rules. After repeated reprimands, the CEO was obliged for a time to implement a morning appearance check at the company’s entrance. Violators simply were not allowed into the office and were sent home to change. Only by means of this rather harsh measure we were able to get all employees to follow the rules. Setting and maintaining such rules is a key part of administration. If no reasonable rules are imposed on employee appearance, behavior, or interactions with customers, getting the company’s work done effectively is in jeopardy.

Therefore, when new rules are introduced that contradict previously established ones — even tacit ones — employees must be made aware of them, and it is necessary to reach a consensus about the changes. After all, in order for a game to take place, every team member must want to follow the rules. If the rules change, it is essential to clear this with the team members, or else they will either try to keep trying to play in the old way or they will even make a game of «let’s show the bosses that they are wrong.» In any case, no good game will come of it.

The second reason why introducing new rules causes employee dissent is more complicated, and it involves people’s yearning for self-expression. Everyone yearns for self-expression. If someone senses an effort to restrict him in this, he perceives it as an attempt to undermine his individuality.

As a result, imposing rules may indeed seem to conflict with freedom of self-expression, but this is not the case. Everyone experiences the urge to become a member of a team, to collaborate with others. One of the greatest pleasures that a person experiences in life is cooperative activity and communication with others. If a person is cut off from communication with others for some reason, he or she suffers. This is why one of the most severe punishments inflicted on criminals is isolation from society, the extreme measure of which is solitary confinement. From childhood on, we are surrounded by friends and classmates; we become members of clubs and engage in group activities with like-minded people. This makes for a full life. Most people have the urge to belong to a group, and not only as observer’s, but also as participant’s who make a valuable contribution. This is also part of self-expression. If this role is missing from a person’s life, he most likely will feel.

So there is no contradiction between consciously accepting some restrictions as a member of a group and expressing one’s own individuality. These are two natural impulses, ones present in every person. If he does not obey the rules of a team game, he will be unable to achieve self-expression as a team member. Therefore, everyone tries to maintain some sort of balance between these aspects of life.

A problem arises only when some person does not want to be a member of a team, and then he perceives any rules of a game as a restriction of the manifestation of his individuality. Conscious acceptance of rules is the necessary cost of participation in such a game. A member of a football team wears the same uniform as all the other players, and he is assigned a number to make him readily recognizable. This is similar to a loss of individuality, but, in fact, it is simply a means of his self-expression as a member of the group. And participating in this game gives him genuine satisfaction. Therefore, following rules that are truly intended to make a person successful in a group activity facilitates his self-expression, rather than restricting it. A real problem arises only when a person does not understand how these vital restrictive aspects of rules contribute to the activity of his entire group.

Disagreement with the rules arises either when the rules really do not facilitate the success of the activity or when employees simply do not understand why they are necessary, important, or reasonable. In both of these situations, the administration is in error, since in people management it should be understood that no matter why a rule is imposed, it is important to know what people think about it.

In my archives I recently came across one of the policies written fifteen years ago. It was a policy about discounts for customers. To be honest, when I read this document, I felt ashamed. There was not a single word in it about why this policy was even needed, what problems it addressed, or how it facilitated the work of the company. It is not surprising that in those days I experienced many difficulties as chief executive. It took a lot of effort to overcome employee disagreement with my instructions. If I, as a company employee, had received such a document imposing a new rule from the chief executive, I myself would have had a lot of questions and disagreements about it.

An unskilled manager can easily kill the spirit of the game just by the way he presents his instructions; rules may be fundamentally reasonable, but if they do not lead employees to understand how these rules facilitate the achievement of goals, people will perceive them as an encroachment on their personal freedom.

Governments have been extremely inept at this; they create laws for reasons that are often utterly unclear for those who are supposed to obey them. As a result, in order to achieve compliance with these laws, it is necessary to create a complex control mechanism and employ an entire army of bureaucrats to ensure that the laws are enforced. Such laws are an example of incompetent administration. After all, no one will dispute the requirements of the criminal code, and its use is obvious to every honest citizen. But with respect to tax law, there is no such unity, because there are many who do not approve of the way their tax money is spent.

Fortunately, everything is much simpler in business, and there are usually no such obstacles to creating rules that are reasonable and that help employees both to achieve self-fulfillment and to accomplish team goals. You could say that proper administration enables a person to maintain a balance between his capacity for self-expression as an individual and his self-expression as a member of a group, thereby making life more harmonious. A common error in this area is giving employees the impression that they work at the company only in order to earn money for a satisfying life.

Some motivational specialists recommend that managers use an individual’s personal goals as incentives and reasons for him or her to work for a company. For example, if a person dreams of earning enough to buy his own apartment or to educate his children, these self-styled experts in people management insist that an employee be convinced that only if he is successful on the team will he reach his personal goals. This is partly true, and good work should be well compensated, and everyone should have the ability to provide himself what he needs for life. But if the sole reason why a person goes to work and performs duties on a team is to achieve his personal goals and he is not concerned that the entire team meets a larger goal, then his life will not really be full.

Imagine that the players on your favorite sports team play only because they need the salary and prize money and that they have no earnest desire to crush the opponent and win the league championship. That would be a sorry situation and contrary to the essence of sports. The late, great football coach Vince Lombardi insisted,«Winning is not everything, but wanting to win is.»

Yet another integral component of a game is the assignment of roles and their corresponding functions in the game. For example, there on a football team are assigned various roles: quarterbacks, halfbacks, running backs, ends, linemen, and others. If the roles are not precisely assigned, cooperation is impossible, and a player will not be able to understand to whom to pass the ball unless he knows his own role and that of every player on the team. In a company, too, unless an employee knows precisely what his work consists of and what others are responsible for, there will be no team.

On any team, there is the role of game creator, which is usually played by the company owner, there is the role of manager (the coach), and there is the role of the specialist (line coach). In a small company, one person may play a number of roles. The role of game creator involves the formation of goals and rules, and it is described in detail in my book The Business Owner Defined.2 The role of a manager is, within the framework of these classifications, to manage specialists, coordinate their actions, and attain high results in work. It differs fundamentally from the role of a specialist and requires special knowledge and skills. A manager must not only understand the specifics of the work for which his division is responsible but must be able first and foremost to manage and motivate people.

The roles in a game are assigned on the basis of a company’s organization chart and job descriptions, and their creation is yet another indispensable administrative responsibility. An approach whereby everyone does everything does not make it possible to create a team and only engenders irresponsibility. Imagine that all the players on a hockey team are responsible for defending their goal and attacking the opponent’s goal. This would create chaos. At the same time, even a poor allocation of functions is better than none at all.

One time, we organized a corporate paintball3 tournament, and neither the majority of the employees nor I had ever played this game before. After the very first round, I simply fell in love with paintball, and now I sincerely believe that it is an excellent means of assessing people-management ability. The tournament took place at a large paintball club out of town that had over a dozen different areas with various structures and obstacles. The employees received equipment, and since there were quite a lot of us, we divided up into several teams. As I have already said, most of the people had never before held a marker4 in their hands and had no experience at all, and therefore they were approximately equal in strength. Naturally, team captains were chosen right away, instruction was provided, and combat commenced then and there. As you might expect, no one could shoot properly, no one knew the tactical maneuvers of the game, and everyone had equal experience — none — and each team had about the same number of women and men. Every team was bursting with desire to win the tournament, everyone was clear on the rules of the game, which the instructors had taught us, and each team had an equal amount of ammunition. But some teams enjoyed a real advantage: those in which the captain, first, immediately assigned roles — who should attack and who should provide cover from a shelter — and, second, led his team in battle.

The winning team was not the one that was in the best shape physically, nor the one that boasted the keenest shots, but, rather, the most organized one. And what’s more, it became clear in the very first minutes which of the captains and team members possessed real leadership and administrative skills. When two teams, each consisting of ten people, meet on the field, victory is determined not by the mastery of a single person, but by the coherence of all the players’ actions. I adore paintball because it consists of very short battles, and if a team captain quickly gets his bearings in the situation, and if the team members actively collaborate, you get a thrilling game. Even the bruises suffered cannot spoil the taste of victory.

If you look at the strongest companies, you can find in them, too, a strong sense of play that is sustained through capable administration. They choose themselves an adversary; they keep score in the game in the form of income amounts or territories conquered. Business is intrinsically a form of game; only the rules of this game are much more complicated than the rules in sporting matches, and in business there are more unexpected obstacles, but the playing field is practically boundless. And, of course, the larger a company becomes, the more skilled the members of the team should be in order to be able to win.

Chapter 2

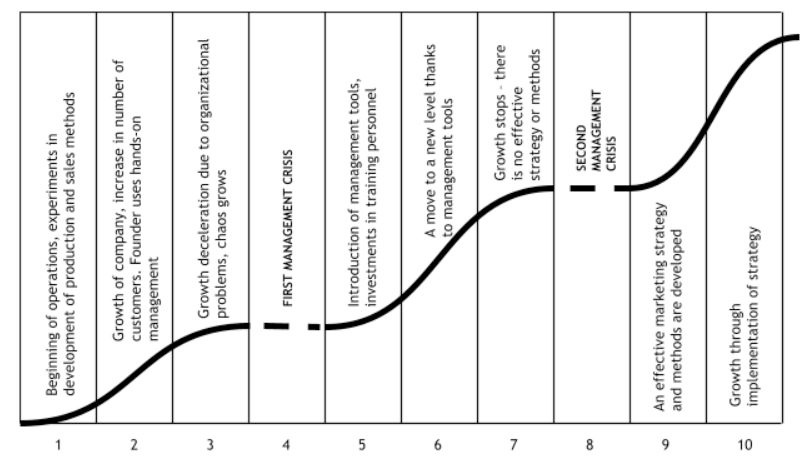

The Ten Stages in Developing a Company

Every company follows a defined path in its development, and you have most likely already heard about these developmental stages in and about the difficulties that arise at the different stages. In the course of my consulting work, I have analyzed over two thousand small to medium-size businesses and consequently identified very specific moments in the development of each company. I am certain that, in reading this chapter, you will easily be able to determine what stage your company is in. This will enable you to better understand the real reason for the barriers to your firm’s development and to predict what awaits you in the future. I want to call your attention to the fact that these stages of development pertain mainly to administration; there can be other factors affecting development, as well.

Stage 1: The Start. This stage is full of hope. At this stage, the company founder tests his idea in practice, and depending on the type of business, he works either alone or with a very small number of employees. In my first company at this stage, there were three business partners who did all the work — sold services and served customers. One of us performed the functions of an accountant; another served as a driver of a vehicle delivering goods. In this start-up phase, the first clients come on board, the first revenue comes in, and it becomes clear how good the business idea was. It is a small team, with no hierarchy of any sort, and duties are allocated according to the principle «You chose it, and you do it.» As a rule, at this time morale is very high and the company’s simple goals are clear to everyone — to survive and begin to make a profit.

At this stage, there are no administrative difficulties, since the duties have been allocated based on the personal preferences of team members. And because there are few people, each of whom works with the utmost dedication, even administrative tools are not yet needed, since the actions of the team members are fairly well coordinated as is. You could even say that there is practically no management at this stage, and that close contact and common goals are amply sufficient for obtaining results.

Very often at this time, the original idea of what exactly the company should provide to clients is transformed, a deeper understanding of client needs and selling procedures is gained, and new products appear. In our computer company, we began by supplying to order everything the client wanted. But very quickly we figured out which products were the most in demand and which enabled us to make more money. We also figured out which categories of clients were the most solvent. As a result, we began to actively develop support services, because we could earn money quickly on small repair jobs. When equipment broke down and work came to a halt, clients were prepared to pay a premium for expedited repairs. Selling new equipment, on the other hand, was much more difficult, since development of that function was not as pressing an issue.

In trading firms, too, the decision is made to promote certain goods to clients, guided by an understanding of the clients’ needs, and in the course of the work what the clients actually need is clarified. At this time, the range of goods and terms of delivery may change completely. You could say that at this stage the business idea undergoes a trial by fire and must be adapted to meet market requirements. Since the company is small, decisions are made very quickly and are also quickly put into practice. In manufacturing companies at this stage, the managers may discover that some equipment that has been purchased has gone unused and that something altogether different is required.

Quite often it turns out that an idea that looked very attractive on paper proves untenable in real life. I have seen several companies, for example, began to offer rapid printing services using full-color printing technology. They opened offices and purchased expensive digital offset printing machines, only to find that they were not using this equipment to its full capacity and thereby failing to make the business profitable. In order to run printing presses at capacity, hundreds of regular customers and dozens of designers were needed in order to put into production at least a couple of dozen different booklets a day. And to build up a sufficient base of regular customers in a market where competition already existed required quite a lot of time and significant outlays for advertising. Therefore, most of these companies ended their life cycle at that stage, sold their equipment, calculated their losses, and began to offer some other products.

You could say that the result at this stage is testing out the business idea and establishing a process of product manufacturing and working with customers. If this can be accomplished, the company gains the ability to develop further.

Many people later look back on this start-up stage as the most exciting time in their lives, although it usually yields little in the way of income or stability. But the high morale and earnest cooperation of team members yield a great deal of satisfaction and good results, and the company begins to grow. Buoyed by success, chief executives begin to expand the company, hire new employees, enlarge the office, increase manufacturing capacity, and purchase equipment or, in the case of a trading company, increase working capital and inventory.

This stage does not usually last long — from a few months to a couple of years. And the more successful the business idea is and the greater the growth it yields at the outset, the sooner this stage comes to an end. For a store, it can end a couple of months after the opening, and for a company that supplies materials to builders under contract, it can last as long as a couple of years.

Stage 2: Rapid Growth. Growth continues, the company expands, and more employees are hired. The CEO manages employees directly as before, guided by common sense and an understanding of the business process. He does it quite well, since morale in the company is still high, and he knows all the nuances of the company’s operations very well. There are still only a few employees, and their activity is very effective, the actions of all team members are well coordinated, as before, the quality of services is high, the competence of employees grows, the circle of clients expands, and income increases. You could say that this is the golden age of the company, since the efforts of the whole team begin to yield tangible results, salaries increase, all members of the team feel like winners, and the future looks bright.

When we reached this stage in my first company, it seemed to us that nothing could stop us and that our future was marvelous. We worked hard as a single team. It was a very congenial place in which to work, since we were not just managers and employers, but also friends. Because the volume of orders was growing rapidly, we began aggressively hiring employees, and the more experienced employees acted as mentors, helping the new hires to get assimilated quickly.

No particular formalities existed, and I had no occasion as CEO to bother using any administrative tools — formal orders, reports, and the like. I believed at the time that all that was needed for management was simply to be competent and knowledgeable about what the company did and to maintain a healthy atmosphere of cooperation within the team.

This stage can go on for quite a long time, and many small businesses get bogged down at this stage for several years, especially ones that require no sizable increase in the number of employees. In some types of wholesale trade, for instance, it is possible to achieve significant growth in company revenue without hiring more employees. In manufacturing companies, as a rule, this is not possible. And since, in my company, servicing computer equipment was a meaningful source of income, we raced through this phase in two years.

Stage 3: Deceleration. The number of customers grows, as does income, but at this time the first administrative problems crop up. Because the number of employees is increasing, an ever-increasing amount of managerial time is spent on management. The first managerial difficulties in the organization of work begin to become apparent — too many different functions rest on the manager’s shoulders. He already has a secretary, salespeople, and an accountant. Each of these has his or her own scope area of work, but many functions are not delegated, so either everyone haphazardly performs them or they become a headache for the manager. These functions usually include hiring staff, advertising, financial planning, soothing disgruntled customers, and much more.

At this time, morale begins to flag. This happens for several reasons. First of all, a manager who is overwhelmed by work forgets to set goals and promote them. You could say that the company gets stuck in the goals of the previous stage — to survive and begin to earn money. The overworked manager does not notice that these goals were achieved long ago and that it is necessary to set new goals, which will unite the whole team. I, too, fell into a trap of this sort at my first company: I was so focused on coping with day-to-day problems that I did not even notice that something was amiss with our goals. Therefore, new employees who were joining the company saw only that the entire team was carried away with the idea of earning more money, which led to a natural stratification of the team into old-timers, who had been present at the creation, and in whom the spirit of the game was still alive, and newcomers, who came on board just to work. When this happens is the team begins to fall apart, yet no one is seriously working on specifying the rules of the game, since the only person who can do that is overwhelmed with day-to-day concerns and is applying hands-on management with each individual employee. Even the old-timers begin to sense that the CEO is distancing himself from them, and that he has changed.

Because of his overload, the manager begins to feel that he is beleaguered and alone, that the people surrounding him are not that great after all, and that they cause too many problems. This is aggravated by the fact that employees usually require a manager’s attention when they encounter problems in their work.

Very often at this juncture, a manager gets the brilliant idea that the whole problem lies with the employees, and a search begins for special employees and managers who can solve the problems and make the headache go away. But, as a rule, this does not make it possible to truly solve the problem, and even if the company is able to attract competent and experienced managers, they cover only some of the problems, which merely defers the onset of the first management crisis but does not eliminate it. It becomes apparent that the company’s expansion is leading to a reduction in operating efficiency. Moreover, usually by this time a company is entering into a new level of competition and coming up against a powerful adversary. The company’s executives, seeing that the growth in the number of employees is not yielding increased profitability, due to decreasing efficiency, stop developing the company, justifying this with some objective reasons — for example, the market situation.

The human mind works in very interesting ways: When we are unable to understand the source of a problem, we cling to some contrived reason for why it exists. Thus I, too, in my time, told myself that the cause of one of our major problems was that the markup on sales of computer equipment was dropping, while competition in the service sector was forcing us to lower prices on our services. I completely ignored the fact that demand was growing and more opportunities for increasing sales volume were appearing, which was also generating more opportunities for earning money on customer service and training. And I stubbornly failed to notice the fact that a lack of administration had become the other main problem in the growth of the company. I preferred to place the blame on circumstances over which I plainly had no control. What is interesting is that the competing company, MacHouse, at this moment was in the very same stage of development, but it was developing successfully at a time when our affairs were going from bad to worse. But it did not even occur to me to study that company’s experience, to look into what exactly the CEO of that company — a person with whom I was acquainted — was doing. I simply did not look at, listen to, nor learn from that company’s situation because I was so convinced that I knew the reason for what was going on in my own company.

Stage 4: The First Managerial Crisis. I can say with regret that my computer company, like most small businesses, did not survive this crisis, it simply got bogged down in it. Revenue growth practically grounded to a halt, and although the company continued to exist for a few more years after I left, its revenue stayed at the same stagnant level. Essentially, the company slowly deteriorated. Having shot ahead into a leadership position in the first stages of its development, it gradually lost ground, and began losing customers and competent employees.

In my next business, manufacturing awards and souvenirs, I ran up against similar problems. Thanks to a successful partnership, though, in which my partner was responsible for design and the manufacturing process, and I for marketing and administration, our business, Heroldmaster, passed very quickly through the first two stages of development and reached the deceleration stage. The company developed rapidly, the quality of its goods was unrivaled, and the number of customers therefore grew. About sixty employees worked at the company, three-fourths of whom worked directly in production, and at any given time there were about eighty orders in production. The average production time required to fill orders was about a month. However, the growth of the company and the absence of good administration led to problems with filling orders; we were missing production deadlines, and the quality of our products began to suffer. Even though revenue was growing and employees were doing their best to cope with all these problems, I had the sense that we had hit a ceiling and that further growth would simply destroy the company.

But this time, I was already better prepared as CEO, and in order to deal with the growing chaos, I began to implement management tools. It was a genuine ordeal for the whole company, but after much trial and error, we managed to establish an administrative system in the company within a year and a half, which enabled the company to reach a new level of development. My partner and I made the manufacturing company Heroldmaster an industry leader and successfully bypassed the deceleration stage. At the time, I was genuinely surprised that our competitors, initially on an equal footing with us, ended up being far behind. They showed no interest at all in how we had achieved success, although all our administrative tools were in plain sight, and we were hiding nothing.

The main problem of companies that have arrived at their first managerial crisis is a lack of understanding of what constitutes the reason for the crisis. The reason is not that something is wrong with the market or with the employees. The reason is that hands-on management is already becoming impossible. With the growth of a business, managing by giving individual instructions to the various employees ceases to work. I am certain that you are familiar with this scene: A manager is constantly on the telephone; he receives dozens of calls a day, gives dozens of instructions, and tries to control everything. One of my customers, whom we were helping to implement an administrative system in his company, said to me in jest, «The cost of the project has paid for itself only by the reduction in roaming costs on my cell phone.» Until then, in applying hands-on management at a company with several dozen employees, he could not turn off his mobile telephone, even when he was on vacation abroad — it would «ring off the hook» from morning until evening.

Hands-on management cannot be delegated to second-level managers because there is no system involved. Accordingly, it is impossible to train someone to do this work. At this stage, therefore, even with the establishment of department managers, the situation remains unchanged. It is also not feasible to make managers out of capable employees, and there is nowhere to get ready-made managers. Lack of management tools is a common situation in business, and therefore finding a competent manager is nearly impossible. Even if it were possible to hire such a person, it would still be necessary to give him some sort of system, some kind of tools. Competent managers cannot use managerial tools if there is no basics system in place — organizational structure, procedures for planning, or rules for financial management.

When a company grows and second-level managers are promoted or hired, the top manager needs new knowledge and skills, and he must have a good understanding of the tools of administration. If he understands work with clients and purchasing, he can manage salespeople and buyers. But to oversee second-level managers, he himself must have a good knowledge of management tools; knowledge of the work process of the company is not enough. It is necessary that a top-level manager have a perfect understanding of the working method of his subordinate managers — administration — and only then can results be obtained. And, of course, first of all it is necessary to create these tools and implement them in the company: planning, reporting, effective company structure, and more.

Stage 5: Implementation of Administration. At this stage, the organizational restructuring of the company is carried out. A company structure is developed for the first time. Planning regulations5, a performance-measurement system, and much more are established. These changes affect every member of the team, and the relationships among the members of the team are completely altered. If all employees have a good understanding of why all these changes are needed, and if the implementation of management tools takes place in the correct sequence, the changes will go relatively smoothly. If mutual understanding among the members of the team with respect to the goals of these organizational changes is absent, such a restructuring of work can be very painful; it will be necessary to overcome the resistance of personnel, which may even result in losing valuable employees.

When we first implemented management tools at the Heroldmaster enterprise, we lost about 20 percent of the employees due to my incompetence. Many of them were individuals who very capable and valuable to the company. Unfortunately, it is difficult to do something really well if you are doing it for the first time. But we were real experimenters then, decisive but inexperienced. In spite of all the problems of implementation and all the mistakes of every description that we made, the result was worth it: The company moved to a new level of its development.

I hope that the information in this book, as well as in my books Org Board: How to Develop a Company Structure6 and The Business Owner Defined will help you avoid common mistakes and enable you to get through this stage painlessly. The introduction of management tools in a company can go very smoothly. I know this because the consulting company I founded has already helped hundreds of enterprises get through this stage. The main thing is to understand very precisely what results must be achieved and to know the correct sequence in implementing the individual tools that are described in the subsequent chapters of this book.

Stage 6: Managed Growth. After effective administration is implemented in a company, the company gets a second wind. There is no longer organizational chaos, and productivity and profit per employee grow. Ordinarily, if a company is not a monopolist, and if market volume enables it to grow, it will experience revenue growth of 50 to 100 percent each year. A management system helps a company to achieve increased effectiveness as well as revenue growth.

Thus, following implementation of basic administrative tools, Heroldmaster achieved growth rates of over 100 percent annually, and I am not talking about completely new markets or products — they did not change; only our company’s efficiency increased. And what is most important — as the company grew, its effectiveness continued to grow, since the duties of each employee became more and more defined and the organization of work ever more rational. At this stage managers go from being deciders of all problems to people who capably manage the work of employees and subdivisions under their supervision. Thanks to profit growth, salaries also increase, working conditions improve, and manufacturing capacity grows. Thanks to an impartial system of measuring the performance of each employee and each subdivision, opportunities for rapid career advancement open up for employees.

One of the characteristic features of this stage is the appearance in the company of managers who take responsibility for their subdivisions and are capable of successfully managing. At this stage the company founder can get out of day-to-day management and work on strategy.

At Heroldmaster, for example, the general director was a young woman who had come to work as a stock keeper and in three years advanced to the position of CEO. She had dreamed since childhood of being a production manager and learned that our company had a vacancy for a section manager. Without yet having graduated from a university or college she submitted her resume to the company. We had an experienced human resources expert working for us, and he saw that the young woman was capable, smart and ambitious. But by then the section manager vacancy had already been filled, and he urgently needed to fill a stock clerk vacancy. So he promptly sold her on the idea that the best career path for a section manager was to begin with the job of stock clerk. She agreed, and by the following day she had already whipped the stockroom into shape — it was in poor condition when she began to work in it.

It took her a couple of weeks to gain an understanding of the warehouse and organize its work, and after that, while continuing to perform the work of stockkeeper, she offered to help one of the section foremen process shift assignments and reports. She did the work so well that when a section foreman vacancy appeared, she got the job. It must be noted that the company already had a very effective system at the time for appraising the performance of the work of each subdivision, and therefore her success in her new position did not go unnoticed. After a time, she became section manager, and then, eventually, director of manufacturing. She ultimately worked her way up to the position of CEO. If not for administrative tools that ensured a very accurate and impartial performance appraisal, this young woman, who was only twenty-five years old when she became a CEO, would have had no chance to of rising to a senior management position. And the company would have lost out, since a talented managerial employee would simply have gone unnoticed.

It is interesting that some management consultants assure owners that by implementing an administrative system, they will have a company that develops on autopilot. Of course it is not difficult to sell this idea if a company is on the brink of its first administrative crisis, because at that point the CEO is ready for anything if only it will relieve him of his problems. The idea of lying on a beach enjoying life while some management system works away is very appealing. There is just one little detail: It does not happen like that, because after tools are implemented, the managed growth stage does not go on forever.

Stage 7: Growth Deceleration. This stage occurs after a company has exhausted its ability to grow by increasing operating efficiency alone. Further growth requires fundamentally new product-manufacturing processes, new approaches to progress, and new markets. You could say that the processes underlying the work require fundamental modification. For example, a company producing roofing materials supplies about 30 percent of the local market, and for further expansion, it needs new territories. But even the most effective work of all the subdivisions will not create activity in a new territory, since the company simply never has had anyone responsible for opening new branches.

What is necessary is to set goals for reaching a completely new scale of development and, of course, brilliant ideas about how to realize them using existing resources. The company owner should play the leading role in creating and implementing these ideas, and if he, by delegating tasks to managers, remains completely aloof from management, the company, having hit the ceiling, will stop growing. If this goes on for too long, the team spirit will gradually die, and the company’s activity will turn into a less-than-productive routine.

State 8: The Second Managerial Crisis. At the stages there are management tools, but there is a little growth, there is not the former drive, and the top manager sees that the company has hit the ceiling. There is still the play among subdivisions, but there is no exhilarating game in common. Instead of striving to reach new goals, the team merely holds its own. Frequently at this stage, a company loses its most successful top managers, since for them the game has already been played, the goals have been scored, and there are no new goals left to strive for. The reason for this crisis is that the company founder has stopped creating the game, and he has delegated day-to-day management to others but has not attended to strategic management.

Interestingly, on several occasions I have encountered companies that have outgrown their founders. Thanks to capable administration and favorable market circumstances, a company’s development may reach a scale exceeding that of the founder’s goals. In this situation, there are only a few likely outcomes. One of these is the replacement of the goal setter in the game, and this can be accomplished by selling the business or by delegating this function by hiring a manager. It must be kept in mind, though, that from this moment on the company will change substantially. Ray Kroc, founder of McDonald’s, once found himself in such a situation when the McDonald brothers informed him that they wanted to get out of the business and demanded that he buy the trademark from them. The scale of the company’s activity had simply become greater than their personal growth, and they preferred to cash in on what they had already achieved and live out the rest of their days in comfort. Another variant is that the company founder must attend to the strategic development of the company. To do this, he will need to reach a new level of competence in running the company, and a new, broader point of view about the activity of the company.

Stage 9: Implementing Strategic Management. This constitutes a short, uncomplicated stage in a company’s development. At this stage, a thorough analysis of the market situation is conducted, and ideas are put forward that will enable the company to function at a new level of activity. Then, on the basis of these ideas, a strategic plan is formed, which then turns into a series of specific tasks, which the CEO takes control of. And the goal setter makes sure that this plan is implemented and, if need be, adjusted; however, implementing the plan is of primary importance. Strategic management tools are examined in greater detail in chapter 12. Implementation of and refining these tools takes about six months. Those involved will find the experience a rewarding one because even the first steps in their use improve morale and take the game to a new level.

Stage 10: Managed Growth. When this has been achieved, the company has everything it needs for enormous expansion, effective management on all levels, high morale, and, as a result, all the employees — from the company founder to the rank and file — are participating in this game. You could say that it is at this stage that real creative work and high results are being achieved.

The ten stages discussed in this chapter are like the ten levels of difficulty in a game. Each new level requires that every member of the team acquires new knowledge and new skills, as well as a general understanding of what is happening with the company.

I hope you have seen which level of development your company is at, so you can be aware of what awaits you in the future. The classification of the different levels in and of itself does not provide a full answer to the question of what exactly you need to do when you discover signs of managerial crises in the activity of your company; this will be the subject of later chapters. But as you set out on your way, it is good to know what to expect, for, as they say, forewarned is forearmed.

Chapter 3

Group Goals

Because goals are the primary component of a game, let us examine the implications. I often hear the idea that the goal of business is growing revenue and making a profit. This, however, is a very limited point of view. Money is nothing but the equivalent of value: If you have money, you can obtain goods and services that you need. Essentially, when a person or a company has a lot of money, it means only one thing: the ability to control any available resources as is seen fit. A lot of money means great opportunities; without much money, opportunities are limited.

Money/capital in business can be compared to energy that can be used to implement an idea, and it constitutes fuel for business, just as fuel for a person is food, air, knowledge, and much more. To say that the goal of business is just making money is tantamount to asserting that a person’s goal in life is obtaining food and having the ability to breathe or to gain knowledge. This is not the case; all people are unique individuals. Every person has certain goals that are dear to her or him: Some want to attain professional heights and win recognition, while for others the goal is to raise capable children. And it is precisely our goals that make us truly individual, while everything else is merely trappings: clothing, cars, houses, degrees, et cetera. These things are only symbols that we use to manifest our own individuality. The adage that money can’t buy happiness is cliched but true. At the same time, though, having money helps us to manifest our individuality, to attain our goals, and to experience happiness. What manifestation of individuality can there be if a person is forced to deny himself the clothing that he likes or if he cannot afford the pastimes that inspire him?

In the case of a company, high profits enable it to attain its goals quickly. A team is able to play more effectively if all the players are well fed and feeling reasonably well-off, when there are no worries about the future, and when all necessary resources can be deployed to win the game. But even so, money cannot take the place of a goal.

The goal of any business and of any constructive activity is simple: to benefit as many people as possible. Depending on the type of activity, of course, this benefit may have various characteristics. For example is the goal of many construction companies is to provide people with comfortable conditions for living or working, and the goal of computer companies is usually to help improve the operating efficiency of their clients. Pharmacists work to improve people’s health and quality of life, and consultants like me dedicate their lives to making the work of enterprises more efficient. By the main goal, in this case we mean a goal that remains constant for as long as the team exists. Of course in any work there are smaller-scale goals, such as opening branches, mastering new processes, or increasing profitability. These are the goals that are specific and measurable and have implementation deadlines. The writer and philosopher L. Ron Hubbard gave a fine definition of goal in his article7 «An Essay on Management»: «Goals for companies or governments are usually a dream, dreamed first by one man, then embraced by a few and finally held up as the guidon of the many.»

The key element in the creation of a team is the formation of a goal, since it is the goal that gives meaning to all activity. Take any type of activity and observe for a while. You will find that the larger the goal, the more capable people want to embrace it, and the greater the inspiration and desire this team will have to overcome obstacles in order to reach this goal.

The members of Greenpeace8 deny themselves comfort and even risk their lives to defend the environment, and they want future generations to be able to enjoy the wonders of nature. Apple strives to make the most modern computer technologies user-friendly tools for people in various professions and types of business. The company Grundfos, which manufactures pumping equipment, defines its goal as improving people’s quality of life and protecting the environment. And if you read books about people who have founded a prominent company, you will find that they all dreamed of creating something beneficial for an enormous number of people.