Бесплатный фрагмент - How the Neonomads will save the world

Alter-globalism edition

ALTER-GLOBALISM EDITION

Many thanks to

The Spirit of the Great Steppe,

My dear wife Asylgul,

My loved brother Bakhtiyar,

Mr. Areke,

And those who influenced me!

INTRODUCTION

Why I wrote this book

The main massage that I am trying to bring across in this book consists of the following elements:

— The heritage and global impact of my ancestral Eurasian Nomadic Civilization is greatly underestimated, ignored, silenced, and even concealed from the modern humanity; and this is one of the most serious deficiencies of the modern world.

— Moreover, this unfair treatment of the Nomadic Civilization is preventing the humanity from solving the myriad problems we face today: ecological, societal, economic, moral, and technological.

— Only the Nomadic Civilization has the answers to all of these vast problems in the future. I proclaim that for the last four thousands years the majority of human civilization was moving in the wrong direction and that we must completely revise everything we know in order to survive and thrive as the species on planet Earth and in our Universe.

These are my strong life-long convictions, and I will try to defend my case in the following chapters.

I write these lines as I seat in a lockdown city of Almaty, Kazakhstan, hiding from the COVID-19 pandemic. The city is completely sealed by the joint forces of police, SOBR, and National Guard. This is the second week of the quarantine caused by the virus that shook the world. The world as we know it seems to be less certain than ever, and the grim future scenarios that have been around in the mass culture of the past decades appears to be unfolding right before our eyes.

We are not allowed to walk outside except for to buy food and medicine; while the schools, offices, malls — everything is shut down. Only the essential government services and food retailers are allowed to work, and the workers wear mask at all times. All of the work that could be performed from home has been switched to a distant online mode, otherwise the workers are on unpaid vacations or are being laid off.

Limited to my four walls and only short runs to a local minimarket, I have no longer an excuse to postpone writing this book, the ideas for which were brewing in my mind for a while. The gloomy occasion is suitable, for I am aiming at nothing less than to offer a path to save the world from self-destruction, and the pandemic is the exact manifestation of the sickness that I want all of us to cure.

Who am I and what are my qualifications? For more information about me read the Appendixes at the end of this book, but here I just want to give a brief.

I come from a few major historical and cultural backgrounds. Underneath it all is my favorite, original, native, Eurasian Nomadic heritage, for I am a Kazakh man born and raised in Kazakhstan, the Heartland of the Nomadic Civilization that existed here for at least three millennia starting from the 2nd millennium BC.

On top of that, as a later addition that came about in the Middle Ages, I marginally represent the Central Asian Islamic realm. Skip forward, and my background is strongly influenced by the Russian Empire in the Modern Age and consequently the Soviet Empire in the 20th century.

Now, in the early 21st century I spent almost ten years living in the United States of America, and this added one more dimension to my mentality. As of 2020 I reside in my native city of Almaty, the former capital of the now-independent state of the Republic of Kazakhstan, and where the COVID-2019 pandemic has caged me in my apartment.

My educational background is in Fine Arts, Art History, and Architecture; all with a strong bias towards Eurasian Nomadic history, traditions and culture. My knowledge and skills are split between academic and practical. Most of my life I worked in a private sector of real economy: television, interior design, architecture, and construction.

At the same time I wrote a book on traditional Kazakh horseback archery, and I am now self-employed as a practical historical reconstructor focusing on nomadic military and civil technologies. Today I spend my days researching about how the Eurasian Nomads made their armors, weapons, bows, arrows, clothes, shoes, horse equipment, and yurts; and then I build replicas and test them in field conditions to learn how it all worked back in the day.

So why do I dare to write a book with such a loud and presumptuous name? I will make many bold statements in this book that might irritate, amuse, or raise eyebrows of my readers, but I ask you to bear with me. Thought I am not an accomplished academic or some guru, in my life I met many interesting, intelligent people of different backgrounds, and we had deep, wonderful, meaningful conversations that taught me a lot about the world we live in. We also partnered in some unique projects that helped me to advance my research and develop understanding of history, culture, religions, technology, and societies.

I am not as well-read as I wanted to be, for I don’t have much time to read and my reading list is three-miles long and I am way behind. But I possess a unique combination of educational background, specific knowledge, unique hobbies, and life and work experience that is not too common even in today’s interesting world.

Therefore, despite all of my shortages, I feel that I still have something to say to the world, and the time has come for it. Hence I wrote this book.

What is in this book and how to read it

This book consists of a few chapters, each of them devoted to a section of my overall statement, and the entire book is structured to be read as easily as possible, to my best abilities.

In chapter The Concept: Eurasian Nomadic Civilization I try to explain what the nomadic civilization was from the point of view of the native carrier of this culture to an outsider observer, because this is the biggest and most misunderstood chunk of human history.

In chapter The Concept: Nomadism vs Sartism I will explain the major conceptual differences between the nomadic civilization and the settled/industrial/post-industrial civilizations as they appears from my Post-Nomadic perspective.

In chapter The Concept: Future NeoNomadism I try to describe the alter-globalism model that I envisioned in my many years of research, observations, thinking, contemplating, and designing.

In chapter The Concept: Future NeoSartism I share my view on how the current post-industrial mode of our civilization must transform in order to become sustainable and stop destroying our planet.

In chapter The Concept: Big Picture I try to combine the two previous chapters and give the overall, universal picture of the future human society, its goal, purpose, and further development in the foreseeable future.

In chapter The Concept: Long-Term Future I outline my vision for the big steps that the humanity must undertake in the next few centuries.

In chapter The Concept: How to Get There I hint as to where we can start implementing the NeoNomadic theory and about the need of a pilot project.

In chapter Conclusion I try to express all of my thoughts in a brief format and finalize this book.

In Appendixes I put all of the information that I thought might make the reading of the main chapters less smooth, but which a reader might find interesting after reading the chapters first. In contains information about me, my influences and sources, the controversy of the terms «NeoNomadism», quick facts about the Eurasian Nomads, and etc.

Read first, criticize later

I understand that many of the ideas in this book are so new and wild that they most likely will be met with some resistance and distrust, to say the least. Perhaps, many will simply dismiss it as a nonsense. However, if one will find it interesting, but not convincing, I urge you to read the whole book first and criticize later, because I tried to foresee the most common questions and doubts, and answer them in advance to my best ability.

Free PDF presentation

Also, if you e-mail me at dbaidaralin@gmail.com, I will send you a free PDF presentation that provides a visual aid for this book.

THE CONCEPT: EURASIAN NOMADIC CIVILIZATION

Concept

Nomadic pastoralism

There is an enormous amount of misunderstanding about the nomadic civilization of the past few millennia. Moreover, the general view on the Eurasian Nomadism is the single biggest misconception known to me within the entire body of human knowledge. It is a complete 180 degree opposite of what it really was historically.

In order to understand the depth and breadth of this misconception, I will have to give a brief crush course on traditional nomadic lifestyle. This is not a history textbook, but it would be impossible for me to explain my theory without diving into the past and giving a clear picture of what the nomadic civilization was like in reality. I will try to paint it with a broad paintbrush in the chapters, and get into more details in Appendixes.

The traditional understanding shared by all cultures in the West and East, paints the historical Eurasian Nomads as vicious, wild, blood-thirsty barbarians, barely humans at all; the orc-like creatures that come and burn, plunder, loot, pillage, rape, and destroy the hand-made miracles of the hard-working settled nations. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam associated the nomads with Gog and Magog, the mythical wild beasty people who will attack the humanity and bring the world to the brink of extinction.

Nobody likes the Eurasian Nomads (EN). They are the classical «bad guys» in human history, who only bring blood spillage, tears, grief, and despair. The Scythians who plundered the Middle East and Egypt in the BC, the Huns who destroyed the Western Roman Empire in AD, the Turkic tribes that terrorized the world in the early Middle Ages, the so-called Mongols who crushed everybody and created the biggest land empire of all times. Most people know of the «maniac» Attila the Hun, or the «bloody-eyed genocidist» Genghis-Khan.

And the humanity have tried to ignore or forget them, just like a victim of violence tries to forget the violator. But in doing so, we made a big, fundamental mistake that is haunting and hurting us ever since. And we will never be able to fix our problems, unless we right the wrong.

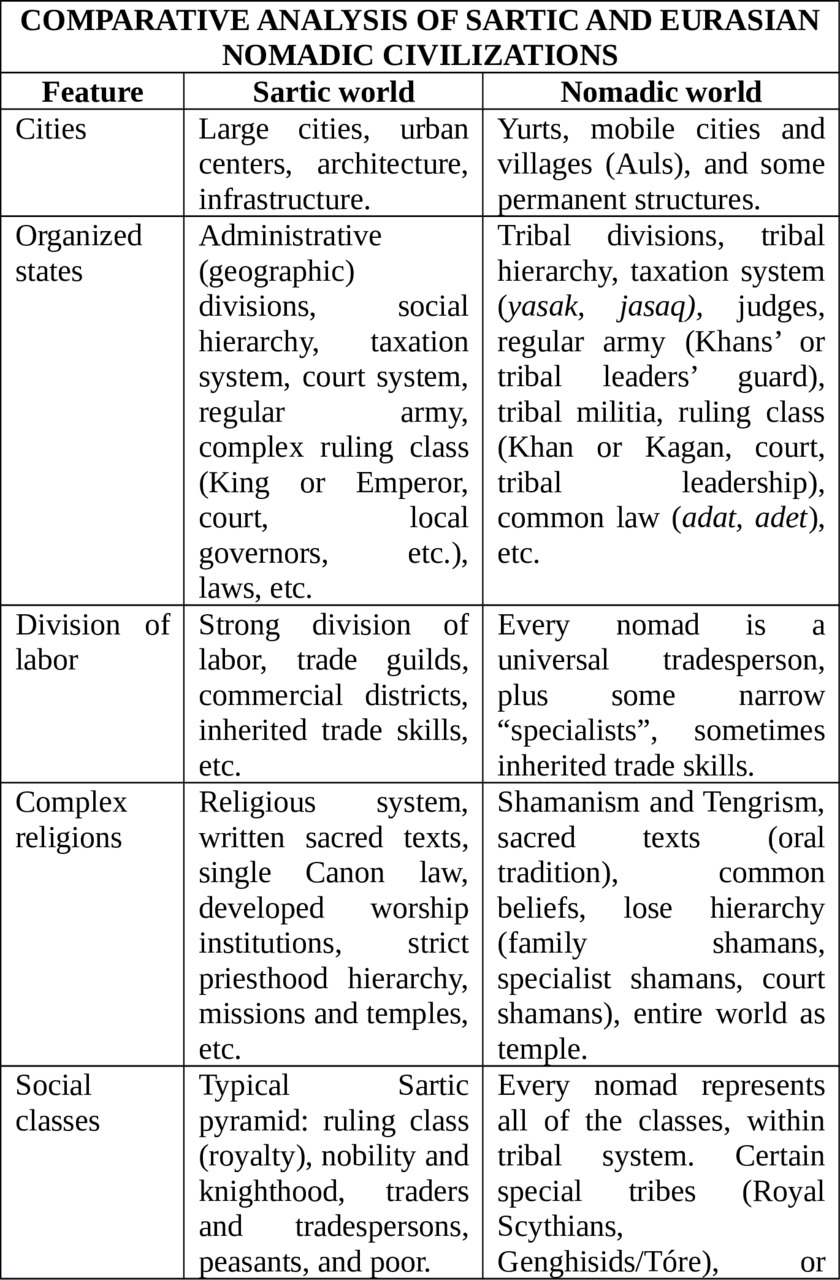

The truth is: the Eurasian Nomadic Civilization (ENC) is one of the two parents of the modern human civilization; the other being the Settled Civilization (SC). The ENC was buried a few centuries ago and we prefer to either never remember about it, or at least to never speak of it other than of a monster. In the meantime, the nomads gave the world many important things, such as governments, statehood, metallurgy, horses, saddles, stirrups, high boots, trousers (pants), topwear dresses, horseback archery, cavalry, wheels, chariots, yurts, felt, rugs, and many more things. I describe this impact more in detail in Appendixes.

The real role of the EN global influence is exactly opposite of what is perceived by most in the modern world. My ancestors were the balancers of the nature, their lifestyle was ideal for ecosystems. I fact, they were the integral part of the Great Eurasian Plains called the Great Steppe, that stretched from the flats near the Altai Mountains to Eastern European Plains. The nomadic model of economy appeared in these lands only because no other type of economy with pre-industrial technology was possible in these barely habitable lands.

The nomads lived in constant migration cycles, following their herds and chasing the seasonal grasses on pastures. They move in a certain way year after year, decade after decade, century after century, and millennium after millennium. Their ethnic composition, the anthropology, language, faiths has changed over the millennia, but the lifestyle remained practically the same. The EN societies closely mimicked each other in their economic and technical aspects, because they were built-in within the nature and were limited to only one possible way of survival: the nomadic pastoralism.

The EN peoples were never as numerous as the SC peoples. The harsh lifestyle, lack of infrastructure, limited technologies and economic powers, and scarce resources never allowed the EN states to flourish to the same extent as their settled neighbors. But this lead to a lifestyle and mentality of valuing only the essential, vital things in life. Even the SC neighbors who severely disliked the nomads admitted that they were the most noble and honest people, albeit brutal and cruel out of necessity.

The main wealth and the economic engine of the ENC was their cattle. The cattle-breeding was the one single most important feature that dominated all aspects of the nomadic life in the times of peace; and in reality peace was the most common state of affairs. Usually the nomads only succumbed to war in extraordinary turns of circumstances, but a vast majority of time they were peaceful and friendly herdsmen. Cattle was the gold of the nomads: they never sold their sheep, camels, or horses for money in order to keep their wealth in coffins. Quite the opposite: they let the beasts roam free in the open fields, only protecting them from the packs of wolves and cattle-thieves. The wealth of the nomadic nations was in their herds: the bigger, the better.

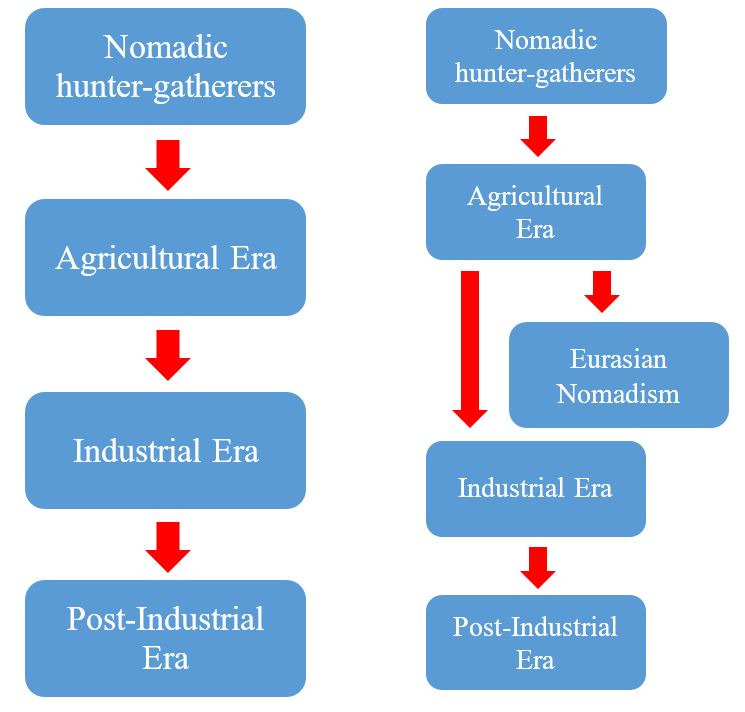

Nomadic hunter-gatherers, Settled Civilization, and the Eurasian Nomads

In order to differentiate the Eurasian Nomads and other nomads, we need to look at some popular misconceptions regarding the phenomenon of nomadism in general.

The most common understanding of the nomads in history is that they were a mistake, a historical evolutional dead-end, an annoyance that must be dismissed and forgotten as soon as possible. At this, many don’t make an important distinction between the nomadic hunter-gatherers, African nomads, Middle-Eastern nomads, modern stateless nomads such as Romani (Gypsies), and the Eurasian Nomads.

The common scholarly view in terms of the human society’s evolution suggests that the first humans were nomadic hunter-gatherers, then these peoples discovered agriculture which led to the Agrarian Revolution and the Agrarian Era, which then led to Industrial Revolution and the Industrial Era, and now we live in the Post-Industrial Era.

The Eurasian Nomads are simply not included into this linear process, as if they never existed, nor they ever created any significant states. At the same time, there are plenty of history books on nomadic empires from Scythian and Hun to Turkic and so-called Mongol. I write more about the history of the nomadic states and empires in Appendixes.

At best, nomads are equaled to the primitive nomadic societies of early hunter-gatherers who precede the agrarian societies. Such is the sad state of things in the modern human knowledge. The nomads are gravely underappreciated, their impact is minimized and their know-hows are unfairly forgotten. Only a handful of nomadologists know the truth, but their voices are never heard by general public.

At the same time, according to the growing number of scholars who study the ENC, the picture of the human society’s evolution looks different from what I described above.

This is what we’ve learned so far about the Eurasian Nomads. After the nomadic hunter-gatherers evolved into agrarians, the later formed first states along the river banks all over Eurasia, where the climate allowed for agricultures to flourish. But the fertility of the arable lands was limited, and the existing technology only allowed for a certain amount of product per area. As the numbers of population grew and also possibly due to the climate changes that diminished the productivity of these lands, some of the agrarians were forced to live in worsening conditions, with hunger threat being imminent.

Fortunately, these changes happened slowly enough for people to adapt. As a result, some people learned to rely on cattle-breeding at first as a subsidiary, and later as a substitute alternative to agriculture. Thus the first semi-nomadic economic models appeared, where parts of extended agrarian families were part-time or mainly cattle-breeders. Later on this specialty lead to a development of seasonal pastoralism, where some families would drive their herds to summer pastures and only return home for winter.

The herds grew in numbers, providing the herdsmen with meat, fats, dairy, wool, and leather. These goods were then exchanged for products of agrarian economy in settlements, thus giving the nomads what they couldn’t produce on their own. This early exchange of goods signified the future relationships between the nomadic civilization and settled civilizations in Eurasia that remained valid until the 20th century, and even still exist today in Mongolia and Northern China.

Soon enough the herdsmen invented ways of full-time, year-round pastoralism. After a few generations, the families of herdsmen gradually became fully independent, and started developing their own type of society, with independent chiefs, military, courts, and other societal institutes. Some even went as far as to completely severe their ties with the agrarian relatives, others tried to live close to them and trade. This allowed for greater freedom in choice of pastures and grasslands, and led to full-blown nomadic pastoralism, which I call the Nomadic Revolution.

The ENC was born in the Bronze Age, it stemmed from the agrarian society, and it existed in parallel to SC for three millennia. And it was successful! There are numerous historical facts that clearly spell the advantages of the ENC over the SC. When the nomads were on the rise, they built their empires in a blink of an eye, and no SC nation could resist them. And they’ve done it time and again, century after century, for thousands of years. Many European, Middle-Eastern, Slavic, Russian, Chinese, Indian, and Iranian dynasties were EN in origin. Please read Appendixes for more detail.

Only in the Modern Era the advancement of technologies and following growth of economic powers allowed the SC nations to finally stall the advancement of the EN, and then gradually turn the tide and start pushing them back into the Great Steppe. Particularly helpful was the invention of gunpowder weaponry, which lead to a mass supply of cheap SC soldiers, who were able to overwhelm the elite EN cavalry.

This process was helped greatly from inside the ENC by endless civil tribal wars that weakened the EN. But even then this process took a few centuries. The EN society was so strong and resilient that it was able to resist the growing powers of the SC nations, which surrounded the Great Steppe from all directions by an ever-tightening rim. Russia was pushing from the north, China from the east, Central Asian Islamic states from the south, and Iran and Europeans from the west. I call it the SC Rim.

Finally, it seemed that the ENC was finished, and finally met its evolutionary dead-end. The SC, finally ridding of the millennia-old threat, proclaimed an ultimate victory, and the ENC was forgotten and written off from the history of humanity. Such was the great fear that even today, after the ENC seized to exist, only a handful of scholars know the truth that remains hidden from the majority.

But is the Nomadic Civilization really dead, forever? I dare to beg to differ and am going to argue this point further in this book. Not only I believe that the history of the NC is far from being over, I even think that this is the only possible way for the humanity to evolve in the future, and remain relevant and prosper.

Economy

Cattle-breeding economy

In order to understand the nomadic civilization better, we need to first understand its economics. It’s fairly simple in the core: the cattle, mostly sheep, horses, and camels, and sometimes goats and cows, eat on wild grasses of the seasonal pastures. As the pastures run out of grass due to overgrazing and drying from seasonal temperature rises, the cattle is moved to next pastures that are still full of the fresh grass. This keeps cattle alive and multiplied in numbers by breeding.

The nomads basically simply follow their cattle herds, and make sure it happens in an organized manner. This closely mimics the great animal migrations in Africa, where millions of zebras, antelopes, and other animals move in the same manner chasing the seasonal pastures. But in the Great Steppe, this took a more structured, man-made form. The herdsmen watch after their cattle, defend them from wolves, cattle-thieves, and other dangers. They also ensure to pick the best routes with watering places, and ward off any possible threats, allowing the herds to roam in a relative comfort.

In exchange the cattle provides the herdsmen families with meat, fats, dairy, wool, leathers, bone, sinew, horns, hooves, and other valuable materials that sustain human lives and production, and feed the economy. The nomads were always careful in using their live wealth, and made sure that not a single fiber of wool goes to waste. The nomadic consumption of cattle was 100% waste-free. Even the cattle dung was dried, stockpiled, and used as fuel to make fire.

Some of the EN always led semi-nomadic lifestyle in areas of the Great Steppe where such economics were possible. One of them being the region where I live — the Almaty Oblast, or Jetysu Region (the Seven Waters in Kazakh language). This region has high mountains and flat steppe right next to each other, creating a unique landscape. The mountain footings in the south of Almaty City allowed for agrarian economy, while the plains in the north were ideal for nomadic pastoralism; all within a few miles distance. Also there were pockets of fully-agrarian societies that lived among the Eurasian Nomads too.

The cattle was, of course, the main source of food. Meat was consumed regularly and by all nomads regardless of their social status; unlike that of the SC nations where meat was a privilege of the rich and powerful. The cattle also supplied the nomads with dairy products: most prominently the delicious fermented horse milk called qymyz and gourmet camel milk called shubat, along with many others. In Mongolia, where the local nomads traditionally have more cows, they make many types of dairy products from cow milk, such as airan, and a few types of milk alcoholic beverages.

This is the basic nomadic economy in a nutshell. It was not complicated in principle, but of course it required tons of expertise on a practical level. The nomads knew everything there is to know about their cattle, given the pre-Industrial technologies. They knew when to move to new pastures, best routes, watering holes, mating and breeding times, sicknesses and cures, as well as the best ways to shear, slaughter, and cut meat. The nomadic cuisine in a pure form contained mostly meat and dairy products, of which the nomads invented many delicious dishes. These dishes were enriched with either natural foods, such as plants, roots, fish, and etc., or with what the nomads could trade off with the SC nations: grains, vegetables, and etc. I write more about the nomadic traditional cuisine in Appendixes.

Nomadic production

The Eurasian Nomads developed their own way of production and industries. Some were advanced and happened for the first time in the Great Eurasian Steppe. For example, the metallurgy. The EN were the first to discover large deposits of metal ore in Altai, Central and Northern Kazakhstan. Most of them are still being extracted today on an industrial level.

The EN were equipped with bronze weapons and tools, when in some pockets of the world people still used Stone Age technologies. When the Altai nomads invented steel production from iron ore and started making steel tools and weapons, it gave them advantage over the Bronze Age adversaries. It helped them to forge mighty empires in the Early Iron Age, and also led to a spread of iron technology all over the Afro-EuroAsia, contributing to a transition to the Iron Age.

These mining and steel productions were stationary, tied to locations where the natural ore were found. Apart from that, the EN learned to provide themselves with all necessities on the move. The ever-roaming lifestyle prevented them from building large manufactures and craftsmen guilds, as it was common in the SC nations. Instead the nomads adjusted their needs and production mode to whatever technologies were possible within the nomadic economy.

The women and youth in nomadic families were skillful craftspersons, capable of producing high-quality felt and animal skins; they weaved wool goods, sew clothes, made yurt’s soft elements, bedding items, and etc. Men were always busy tanning the animal leathers and making leather goods: saddles, leather armor, belts, pouches, boots, horse and camel harnesses, and etc.; woodworking: building the yurt parts, furniture, wooden dishes, making bows and arrows; ironworks: making tools, weapons, equipment parts; and pottery. All of these works were produced either right in the yurts or simply outdoors, without city walls, factories, and shops.

The nomadic families were able to produce goods to cover 100% of their everyday needs. Of course, they never skipped the opportunity to buy or exchange goods with their neighboring SC nations. In fact, many nomadic tribes were heavily involved in trade, either directly or by providing security for passing trade caravans, especially during the Silk Road era. But overall they could get along on their own with complete self-sufficiency.

Therefore, we know that the nomadic production was highly versatile, adaptable, mobile, resourceful, ecological, minimalist, and waste-free. This is an important quality, as I will show how this approach can become crucial in the future of humanity.

Nomadic Dwelling

Mobile dwellings

The Eurasian Nomads also developed an entire new approach to living accommodations and comfort. Most of the EN mobile dwellings represent variations of a tent. There are a few types of these, incorrectly referred to as yurts. I describe this more in detail below in the Appendixes. Here it is sufficient to say that the Kazakhs call a yurt ui and the Mongols call it ger, while the term yurt («jurt» in Kazakh language) refers to a place where our EN ancestors used to put the uis and gers. But for the sake of convenience, I will continue calling it «yurt».

There are a few theories on how the modern-day Turkic (Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Turkmen, Bashkir, and Karakalpak) and Mongol yurts originated. One theory is that they represent a further evolution of a more primitive tepee-like conical tents that still exist in Siberia (chum, yaranga). The simple and narrow conical tents gradually became spacious dome-shaped tents with separate walls and roof. Through a series of improvements they arrived to their modern design. Other theory suggests that they repeat the design of Bronze Age’s stationary wigwam-style houses of the Eurasian agrarian societies. In this theory the early nomads were trying to adjust the old design to new conditions.

Whatever the origin of the yurt is, we know that by the Modern Era the yurts have evolved insomuch that even today we are still discovering their secrets and admire their design and engineering. Today there are modern-day yurts made with traditional materials and technologies, as well as high-tech yurts made with contemporary materials and technologies.

The yurt is mobile, collapsible, portable yet durable, comfortable and universal dwelling. Over the millennia the EN learned to make them climate-proof, wind-proof, and weather-proof; as well as pleasant to spent time in. They allow for a cozy, convenient lifestyle all year round, while living on the move. These are not your typical tourist tents, or even the military tents that are designed to provide for temporary shelter. The yurts are actual permanent houses, richly decorated and well-furnished, warm in winter and cool in summer; the only difference is that they are made to be fully portable.

The yurts were well-equipped with all necessary furniture and household items for a comfortable life, but without unnecessary extra stuff that clutters the houses of the SC peoples. The ground and walls were covered with woven and felt rugs, providing insulation and weatherproofing. The yurt dwellers had small portable tables, compact cabinets, kitchenware and dishware, many bedding items, and sufficient amount of clothes for all four seasons. The nomads rarely used chairs, because they were just an extra weight during the seasonal movements; instead they preferred to seat cross-legged on the rugged floor. The usually slept on soft matrasses that they put right on the floor, only using portable collapsible beds to sleep their kids or elders.

Overall, the yurt is an ingenious invention of the EN, ideally suited for nomadic lifestyle, and perfectly balancing comfort with practicality.

Nomadic Transportation

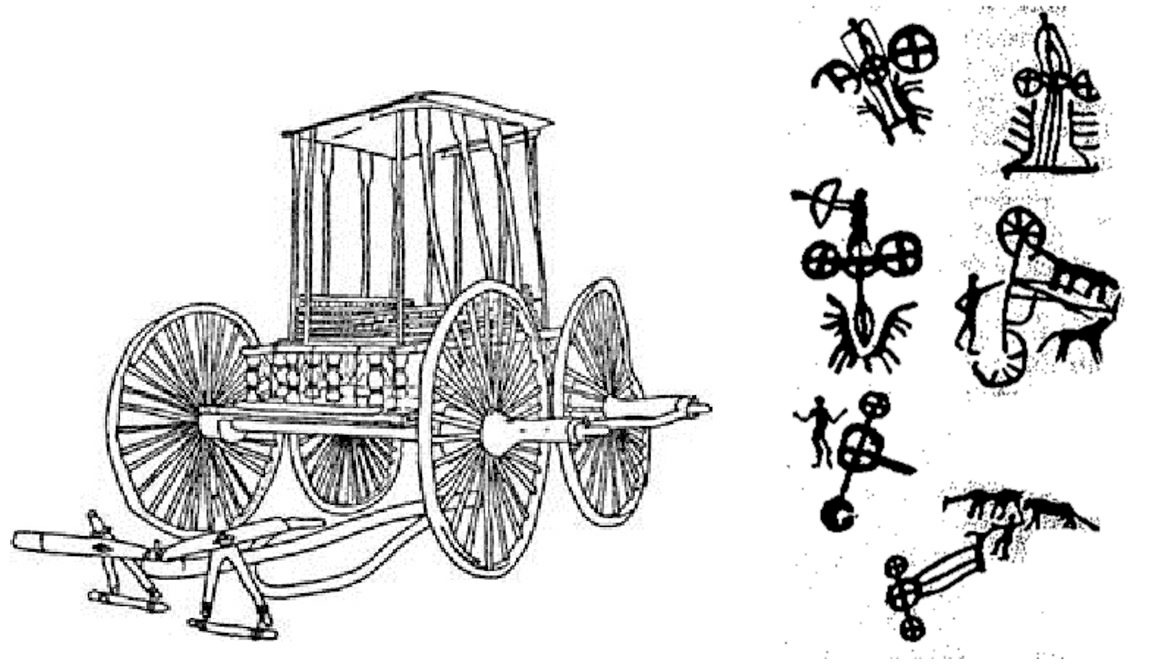

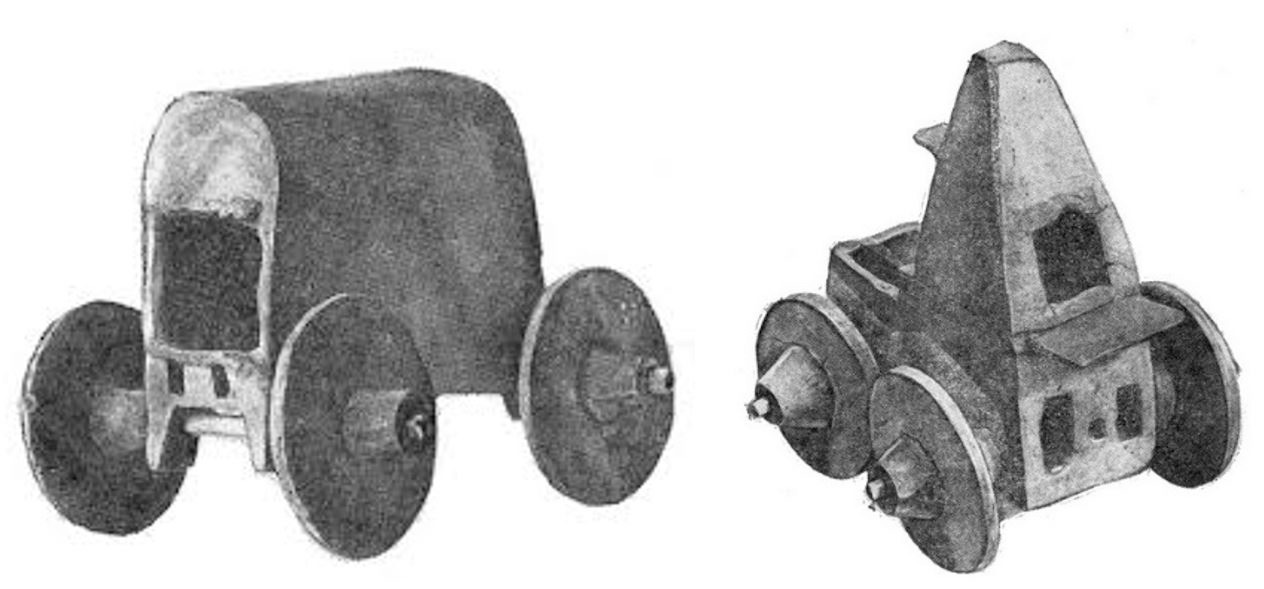

Chariots and wagons

The Eurasian Nomads also made a revolution in transportation. Not many people today realize that the wheel was an EN invention. As we know from archaeological evidence, such as the Botai Culture in Central Kazakhstan and others, the early cattle-breeders didn’t ride horses. Horses were herded mostly for food or ritual purposes, because they were much smaller than modern-day horses and weren’t able to carry a rider. Therefore, to use them as transportation, the nomads had to invent pulled carts on wheels, which later led to a development of chariots and wagons. Chariots, in turn, evolved into feared war chariots, a trademark tech in most of the Ancient world.

This technological evolutions got spread all over the Afro-Euro Asian world of the Bronze Age by the early EN conquerors, such as Cimmerians and others. Horses and chariots were widely adopted by the settled nations of the Middle East, Egypt, Greeks and Romans, Persians, Indians, and Chinese. Having more resources and production power, these settled civilizations learned to mass-produce the chariots and created large armies reinforced with chariot units.

Wheeled wagons formed military wagon-trains that took loads from shoulders of SC foot-soldiers, and allowed for more provisions to be taken in campaigns. This made army marches to go much faster and cover longer distances. This explains the raise of the SC conquerors and formation of early SC empires of Antiquity.

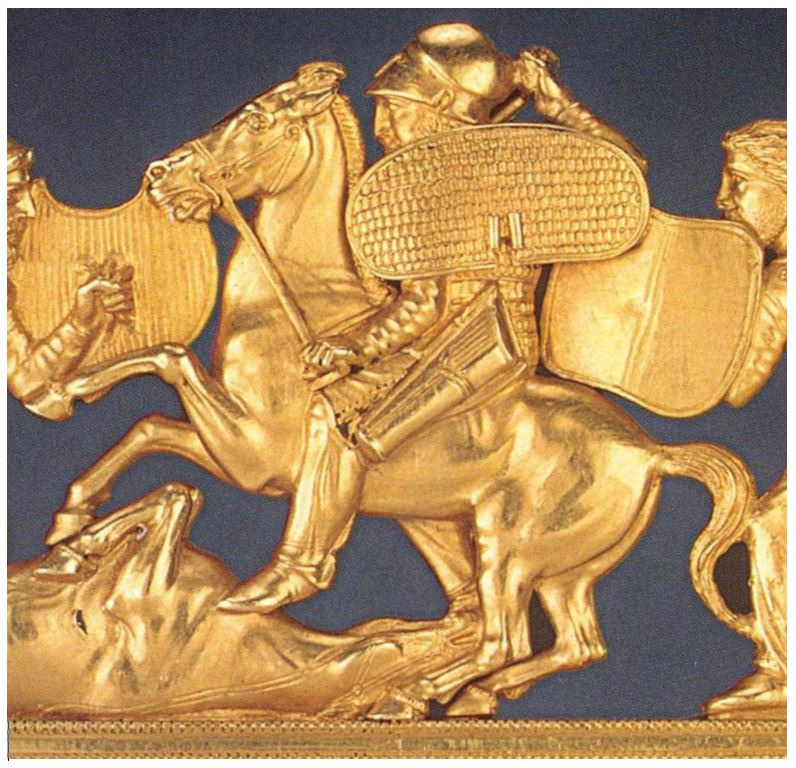

Ascent of Centaurs

But the EN once again showed their ingenuity and persistence: they gradually bred larger horses and learned to mount them, resulting in a brand new phenomenon — a horseback rider. At last, the true Eurasian nomad was born. Now a person could ride for longer distances and be more swift and maneuverable, and pass through terrains not suitable for wheeled chariots and wagons.

Soon enough the military use of horsemen followed, and warriors on horses outperformed the charioteers. Both horseback archers and heavily-armored shock cavalry were more deadly and efficient than chariot archers and warriors. Also, a soft leather saddle and harness of early design cost a few orders of gratitude less than very expensive chariots. Gradually the wheeled combat vehicles went extinct in the Steppe, giving place to mighty Centaurs: people so comfortable riding horses that they seemed to be one creature.

Of course the SC followed the suit and developed their own cavalry. This was a true arms race: everything the EN developed to win in wars against the overwhelming nations of the SC Rim, the later adopted after a while and started using against the nomads and each other. At this, the SC nations always enjoyed larger resource bases and virtually limitless amounts of recruits, whilst the nomads always had scarce numbers and resources and had to rely on their wits and skills.

So the Eurasian Nomads stroke again by developing a system where each horseback warrior took a few extra horses with him or her. This allowed the horsemen to change horses without stopping to rest them, so now they could cover long distances with great speed and hit enemies where they didn’t expect. Another words, the nomads used the advantage of having more horses that any SC nation in history: each nomadic family, even the poorest, possessed at least a half dozen horses, where the rich families had them in thousands. Therefore the EN could easily gather large and completely mounted armies in short time, a capacity that no settled nation could ever match, which gave them a long-lasting advantage.

Further evolution of wheeled transport

Arms races aside, the nomads also invented many interesting types of transportation for civilian usage. The wagons were one of them. The first wheeled carts were simply flat platforms on wheels pulled by horses or oxen. Then the nomads figured out that if they add some sort of roofing on top of a platform, it provides an additional protection from nature elements, as well as predators. The wagon is much more versatile and useful than the simple open cart.

Another absolutely amazing and ingenious invention of the EN was the yurt-cart: an actual fully furnished yurt being placed on top of a large, heavy, wheeled frame. The yurt-carts were of various shapes and sizes, ranging from early small livable wagons of the Bronze Age, to small and medium sized yurts on carts, and to large and luxurious Khan’s yurts on wheels during the so-called Mongol Empire that required dozens of oxen to pull them.

Having a permanent home mounted on top of a moving cart was a big advantage for nomadic lifestyle. It saved time for putting/taking down yurts, and the nomads really valued their free time. Plus, it allowed for more comfortable moving conditions. Imagine entire cities of yurt-carts, many of which were beautifully decorated, moving slowly on the endless plains of the Great Steppe! That must have been quite a sight!

The concept of Kósh

Seasonal movements

The pastoral nomadism required well thought-out order and systemic approach. There typically were four seasonal movements, called qystau (winter camp), kókteu (spring camp), jailau (summer camp), and kuzeu (fall/autumn camp).

The overall traditional patterns of seasonal nomadic movements in Kazakhstan were as follows: the winter camps were located in the south, near the hills and mountains where the winters were relatively softer; the summer camps, on the opposite, were at the far north plains up to 1,500—2,000km (1,000—1,300 miles) away from the winter camps; where the summer heat wasn’t so scorching and grass still remained fresh for the cattle to feed on. The spring and fall camps were located intermediately in between.

The winter camps usually had some permanent structures, such as cattleyards, sheds, storages, outdoor kitchens, and sometimes even permanent houses, or at least heavy winter yurts that weren’t moved to the summer camps. This is where the nomads were seating and surviving the harsh Eurasian Steppe winters. The only outdoor activity at this time of year was hunting, as the travelling between the camps of different families and tribes were limited. This time was used mostly to make or fix equipment for the next season: sew new clothes or patch the old ones, weave wool goods, make leather goods, and etc.

The new year in the Great Steppe usually started on around March 20th each year during the spring equinox, when the duration of day and night were equal. The kickoff event was the Nauryz celebration, when the nomads came to see each other to make sure everybody survived the winter and the cattle made it too. The last remaining winter stores of food were consumed in a big communal feast in which everybody got to participate.

This is when the EN started leaving their winter encampments and moving towards their spring camping sites. The spring camps were typically located at hilltops or other shadeless places free of thawing waters and open to fresh air and sunlight. The pastures were full with new growing grass, and the cattle was gaining weight fast and also lambing and foaling was taking place. The cattle was sheared and this spring wool was called «dead wool» and stored for future use.

The next big seasonal move happened when the cattle ate all of the grasses around the spring camp and the heat and sunlight scorched the ground. Running away from deadly dry seasons, the nomads undertook a long migration towards their summer camping grounds in the north. This is where the sun is less ferocious and there are more small woods with protecting shade, and the rivers don’t run dry all year long. The summer nomadic camps always settled around riverbanks with access to water and cool air.

In the fall there is a third seasonal movement, now back towards the south. The fall camping could be at the same place as the spring one, or some other suitable place. This was the best time of the year for the nomads. The cattle is fat and plentiful, the people are healthy and full of energy. This is where many of the nomadic production works happen, such as mass cattle shearing (fall shearing), making felt for yurts, woodworking, and etc.

Also this is where the most delicious event in the nomadic life too place: the massive fall slaughter of cattle called «soghym». The carefully selected animals were slaughtered in large numbers, and their meat was salted and dried to be stored over long winter. This is the only time of year when there is plenty of meat for everybody to eat. And because of that, this is when most of celebrations take place, such as marriage brokerage and weddings.

After the end of fall season, nomadic families traveled to their winter facilities. Here they put their cattle in fenced yards and stored hay for winter. Once the snow fell the nomads were seating out for a few cold month: eating on their food stores, feeding the cattle with hay, making and fixing their equipment, and hoping that the spring will come on time. And the cycle repeats again, year after year, millennium after millennium.

Such was the typical seasonal migration cycle of the Eurasian Nomads. In Kazakhstan the winter camping grounds were located in modern-day Southern Kazakhstan bordering with Central Asian states (Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan), while the summer camps were located around the northern border with today’s Russia.

Over the thousands of years the nomadic seasonal migrations were perfected to a solid system. Each tribe had its own route (a corridor) and camping grounds, with designated watering holes and pastures. Only tribe members knew the best locations and paths, and could deliver their caravans to the destinations safely and efficiently. Other tribes, in times of peace, never violated these unwritten rules. In times of war or famine, however, these routes and grazing grounds were often becoming battlegrounds between rival tribes.

In Kazakhstan the process of moving from one seasonal camp to another is called «Kósh» as noun and «Kóshu» as verb, and the proper name for the word «nomadic» as adjective is «kóshpeli» or «kóshpendi».

Nomadic leisure

Culture, poetry, and music

Contrary to the erroneous commonly established opinion, the Eurasian Nomads were probably the most cultural people that ever existed on Earth, in the nomadic meaning of «cultural» that is.

The reason for that was that the nomadic lifestyle didn’t require working long hours from sunrise to sunset every day, like in was for farmers or craftsmen in SC nation. Instead, the life of nomad consisted of massive, labor-intensive, but short efforts, such as four seasonal Kóshes, collective cattle shearing, felt-making, soghym, or swift war raids and military campaigns; alternated with long periods of relative calmness and leisure time.

And that leisure time was used mostly for cultural activities, arts, sports, and other pleasures. In fact, despite the harsh lifestyle, the nomads most of all valued quality time and used any occasion to throw a party. Whenever any guest, even a complete stranger, came to any yurt, he or she was admitted as a dear guest with the most respect and consideration. This was a universal law of the nomadic hospitality in peaceful times. First feed the guests, water their horses, and then ask questions. This law never changed for thousands of years.

Then came long conversations that could last for days and nights for as long as the guests were willing to stay. And if the guests possessed some valuable skills, knowledge or talents, this could easily turn into a big holiday event for the whole nomadic extended family called Aul, or even an entire tribe.

If a guest could tell good stories, old fairy tales or legends, if he was well-travelled or educated, or if she knew how to play musical instruments and perform songs and poetry, this was the happiest occasion and honor for the hosting family. Such a guest was like a pure gold, and the hosts didn’t spare any expenses or efforts to please him or her and their neighbors. The sheep was slaughtered for meat, and the horse milk qymyz and camel milk shubat was consumed in mad amounts.

The oral literature tradition of nomads was simply enormous. Unfortunately, very little of it survived to date, because the nomads rarely used writing and the poetry was passed on orally and thus was forever lost, forgotten in the folds of centuries. The roots of European traditional poetry, such as minstrels, bards, saga-tellers, and singers, lies in the EN oral tradition. At this, the later was not limited to the nobility, and was vastly greater and encompassed all layers of nomadic society. Every nomadic Aul and tribe had one or dozens of poets, musicians, and singers, and they were distinguished and nurtured by their families and neighbors.

There were a few types of poets in the Great Steppe. Some were only performing old legends and sagas, others specialized in moral and philosophical poetry, and others used their poetical talents for politics and social criticism. Often the EN staged poetic battles between the specially-trained fast-rhyming poets, similar to modern-day rap battles. There were even the shamanic poets, who used poetry to cure the ill, strengthen the weak, restore the fertility, stabilize the mentally-ill, and etc. There were also poet-warriors, actual combat participants, who used their poetry to raise the moral of their tribesmen and humiliate the enemy.

The Eurasian Nomads loved music even more than poetry. One could be simply blown away by the amount of musical instrument types that the nomads invented on their own or adopted from their neighbors. There is the Museum of Kazakh Musical Instruments in my city of Almaty, and it has a great variety of items on display, but this is only a tiny survived fracture of what the nomads used to have. There is a big array of string instruments, string and bow instruments, wind instruments, percussion instruments, jaw harps, string harps, bells, whistles, and etc. There is even an instrument made of horse hooves. Looks like the nomads were obsessed with making sounds of music out of everything they could get their hands on.

Just as there were many types of musical instruments, there were also many types of musical forms. Some are sad and long, others are short and furious or funny, merry, and spirit-lifting. There was a big cluster of love poetry, of course. There was war music, and drums with tambourines were used as signal tools in the armies. Some musicians were able to imitate dozens, if not hundreds of nature sounds, such as hooves rattle, birds singing (different species), wind blowing, water flawing, and etc.

Of course there were singers too, who were able to play instruments and sing. Those were the skills that pretty much every single nomadic girl or a boy were expected to master at least to some degree in their free time, unlike that of the SC nations, where mostly the privileged class could afford a luxury to study and perform music.

Arts and crafts

The Eurasian Nomads were also proficient and prolific in arts and crafts. To put is simply, they tried to turn everything they touch into an art piece. Free of city walls and houses, not burdened by the need to cultivate the land or watch after the gardens, having only the most necessary possessions that their cattle can carry, most of the nomads didn’t have hoarding addictions of the SC people. Plus, unlike the later, they had tons of free time on their hands, and also never developed the division of labor to such a degree as it was in the settled societies. Therefore, they were much freer to engage in artful activities.

Each EN was crafty and skillful, and able to perform most of handwork tasks. All nomadic women were taught to sew, weave, and make felt. And all of the men had basic woodworking, leatherworking, and metalworking skills. Of course, there were exceptionally gifted craftspersons who could specialize in certain narrow process-oriented trades, such as yurt making, bow making, smithcraft, and weapon making, and it was considered a blessing from the Skies. But even the least talented nomadic man or woman could equip and decorate their yurt and make their own clothing.

Even the neighboring SC nations noted this quality of the nomads, not without some envy. On the average, the EN were skillful, versatile, resourceful and imaginative. The Kazakh yurt, fully decorated and equipped, is a masterpiece of the highest grade. Every square inch of it is decorated with textiles, weaved patterns, ornamented felts, beautiful rugs, bedding items, linens, and etc. The dressing was also decorated with embroidery or applied patterns. And most men knew how to make good looking leather goods that could be embossed or stamped; wood carving; or even metal jewelry. Much effort was spent on decorating the horse equipment: saddles, saddle pads, stirrups, harness, and etc. And, of course, men would go out of their way to make their weapons look good too, as the weapon was a sign of manly status.

The nomads wanted to live beautiful lives in accordance with their aesthetical views. They wanted their mobile dwellings to look and feel like home, and spared no efforts to achieve that. The nomadic mentality was simple: I don’t change the surrounding nature and I don’t have much possessions, but I do carry my home and my belongings with me all my life, and I want them to look real good.

Sports and games

A big part of nomadic leisure time was spent in highly developed traditional sports and games. The sports always played a special role in the nomadic lifestyle. Every event, every celebration must have had sporting events. The EN invented myriad of sporting games and competitions, of which only a fracture survived and known today, but it was enough to establish the World Nomadic Games that first took place in Kyrgyzstan in 2014.

The EN games could be roughly divided into a few categories: games involving horses, military games, wrestling and fist-fighting, and individual and team competitions of various kinds.

The horse sports were particularly developed since the Eurasian Nomads were the history’s most prominent horse people, the true Centaurs. They included various types of horse races, such as speed, distance, and insurance races. There were team sports, such as kókpar (goat dragging), horseback wresting, and picking up small object from the ground on full gallop, chasing a girl on a horse, horseback polo, and many more.

The military sports included horseback and foot archery of many types, competitions with spears and lances, javelin throwing, jousting, and etc. The nomads invented knightly tournaments, where the competitors, armed with dull spears or lances, tried to knock each other off the horse. These and other types of jousting were played as duels or in teams, and served as training exercises for future combat use.

These nomadic tournaments migrated to Europe together with horse-riding culture, and became the foundation of the future European knightly tournaments; except for in Europe it was only the privilege of the wealthy, while in Eurasian Steppes every nomad could participate and win regardless of his or her status. In Kazakhstan these tournaments were popular among the population and existed until 1920s, when they were finally officially banned by the Soviets.

The foot military disciplines had a few types of fist-fighting and wrestling, one of which survived today as qazaqsha kures (Kazakh wrestling). Of course there was fencing, dueling, swordplay, spearplay, axeplay and other types of combat sports performed both on foot or horseback. The nomads were skillful warriors who knew their way with all types of weapons. This was a universal matter of survival.

And when the Eurasian Nomads weren’t busy moving, fighting, watching after their cattle, or partying, playing music, reciting poetry, playing sports or taking part in military competitions, they entertained each other by playing regular games. There was enormous amount of games that the nomads invented, borrowed, and helped to spread around the Afro-EuroAsia. There were riddles and puzzles, jokes and mockery, active games involving throwing objects, kids games such as hide and seek, tag, tug of war and its variations, and etc. There were even romantic and erotic games for young adults, and brain-stimulating games for seniors to help them to keep their memory sharp. And many, many more.

The nomads also tried to turn every work into a game. During the intense Kósh times, the EN wore their best clothes, garments, and accessories, and travelled merrily and loudly, while signing song, and bursting into horse races or chases. The youth used the Kóshes as occasions to meet new friends and make romantic connections. On the camping grounds, when the nomads had to perform some labor-intensive group tasks, such as felt-making, they would engage is games, specifically designed to make their work go faster and merrier; as opposed to dull everydayness routines of the SC farmers or craftsmen that performed repetitive tasks all their lives.

The nomads knew how to spend their time well, and they had the means for that: time and wealth. They lived in the world where every winter could be their last one: the nomads never had more than a few months-worth of food stores, so there could be hunger in the spring; where the enemies could strike at any time and there were no walls to hide behind, where the disease could wipe out the entire regions, as with the infamous Black Death in 14th century that started somewhere in Central Asia, got spread along the entire Silk Road and wiped around almost a half of the population of Eurasia.

Given all that, the nomads tried to value every living minute, and they did that by creating a vastly developed culture.

Nomadic society

Political system

The closest we can describe the EN society in SC terms would be a direct military democracy with strong remnants of matriarchy. All adult population took part in elections, and every voice was counted. In a nomadic version the leadership must have possessed extraordinary and universally accepted merits in order to be elected. The chief or chieftess must have been a great warrior/warrioress, be honest and honorable person, have political and economic wits, know traditions, be adequate and qualified for the job, have good orator skills, and etc.

Surely, it didn’t always exist in a pure form. In areas where the nomads came in close contact with SC nations or led a semi-nomadic lifestyle, they adopted many features of their settled neighbors. Also, there were a few periods in history, when there were native EN ruling dynasties, such as the Royal Scythians, the Ashina Turks, or the descendants of Genghis Khan called Tóre (Genghisids). These dynasties overruled the direct elections and passed their status to their heir. But even they had to listen carefully to what their freedom-loving subjects need. Otherwise, the rulers would’ve end up without their people, as the nomads could simply move away from their leaders, if they didn’t meet their expectations.

But there were also long periods of time in remote areas of the Great Steppe where the EN lived free in accordance with their own laws, and the ruling class was elected during direct voting among the most merited and distinguished members of the nomadic society, both male and female. In fact, most of the nomads didn’t like the idea of electing Khans, they preferred to stop the hierarchy at a tribal leadership level. Khans were usually needed only in times of war.

Being the EN Khan was no easy feat. The people knew their rights and powers, and they could deposit any ruler just as easy as they elected him or her. The leaders were held accountable for all their actions, and often were killed or sent to exile if they didn’t deliver. Therefore, competing for power in such societies was the best example of meritocracy of the elites.

Social structure

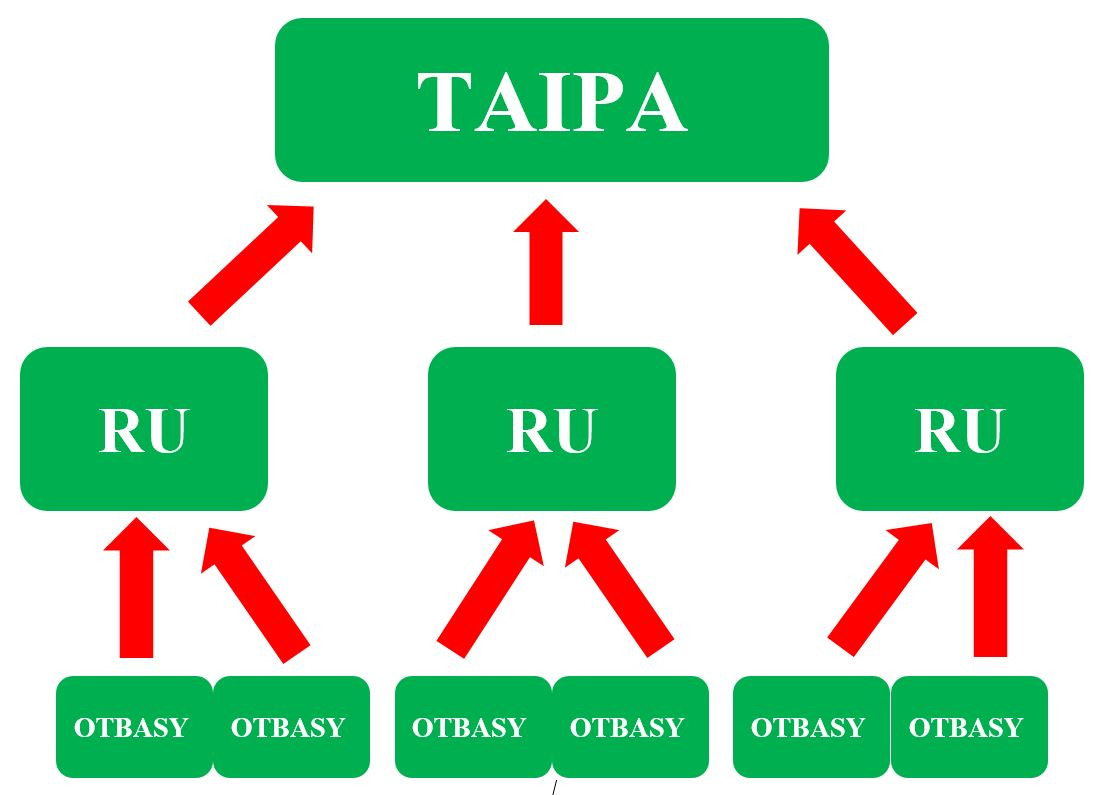

As for the structure, the nomadic society was built of a few families forming nomadic villages called Auls, which entered extended family clans called Ru, the Rus were part of tribes called Taipa, and tribal confederations were called Orda (order) known as Horde in English. Each of these had their own head, usually it was a man, but distinguished female leaders weren’t rare at all on all levels.

The leaders were full-scale military leaders, marshals and generals, and were personally leading all military campaigns. The tribal chieftains and Khans lost their lives in battles on regular basis, as it was a dangerous life. If a family lost their male leader, or if a Khan was killed at war, usually his oldest wife would take his place until his sons reach the age of maturity.

Men died in wars too often, therefore, there was always a lack of them in the nomadic society, leading to excess of single women. To offset this negative balance, the nomadic males would usually take a few wives and try to produce as many male offspring as possible, knowing that most of them won’t live long enough to mature. Even so, these measures could barely replace the male losses. So there was an institute of secondary marriage, where any widow would marry the remaining male relative of her killed husband, and he would adopt her children and raise them as his own. This was a far better option for most women than to be left alone in the Steppe with children and possessions to meet a certain death.

Other wives were not against it, because they knew that this tradition was developed over millennia as an insurance policy in women’s benefit. Any woman might end up needing it at any time. As for men, knowing that their children will be taken care of by their kin in case of their death made them braver warrior. This is why the nomadic warriors could afford to die for honor on the battlefield.

Military system

All males were considered warriors upon reaching the adulthood, and were attached to the tribal militia forces. To be efficient, all boys without exception were trained to be warriors from the earliest possible age. This rule also included all girls too, because not only they were expected to be able to protect themselves, but the nomadic women were also default auxiliary cavalry reserve in times of war. Therefore, all nomadic children, boys and girls, were trained and proficient in handing the Five Weapons (Bes Qaru), the nomadic martial arts system which included weapons such as bow and arrows, lances and spears, sabers and swords, clubs, warhammers and battle axes, and daggers and knives. All of these Five Weapons were used both on horseback and on foot.

European knighthood takes its roots from the EN tradition of the Great Steppe’s knights called Batyrs (bahadurs, baatars). It is a well-known fact among the Eurasian nomadologists. The Batyrs were the elite tribal warriors who rose to their ranks only due to their military accomplishments. The Batyrs were noble by the nomadic standards, extraordinary warriors and military strategists, also were well-educated, accomplished in arts, poetry, and music. The status of Batyr was not passable to their children and could only be earned in battles. Sometimes even Khan’s were given the status of Batyr. In some respects, the title of Batyr was higher than the status of Khan.

Leadership

The decision-making process in EN society was also unique. The family heads (Aul-Bas) would elect the clan head (Ru-Bas), and the assembly of the Ru-bases would elect their tribal leader (Taipa-Kósem). The Taipa-Kósems would form constituent assemblies of tribal confederations. These assemblies were to hold democratic leadership meetings called Qurultai, where they would discuss the ongoing matters, such as coordinate their seasonal migration routes, solve any possible disputes, and etc. Each of the Taipa-Kósems had a voice and the decisions were made by voice count.

In times of war or famine, the Qurultai could have decided to appoint a marshal or even elect a Khan. At this, in order to elect a Khan, the circumstances must be extraordinary, such as long war with an adversary state or another nomadic tribal confederation, because the nomads never liked the idea of concentrating too much power in one hand. The marshals would usually be appointed from the ranks of the most experienced and accomplished Batyrs. Sometimes, the Qurultai could even combine both roles and elect a Khan with marshal’s privileges.

For the most part of history, nomadic Khans had limited powers. First of all, the elected Khan would have to give out all of his cattle (main wealth) to the tribes that elected him. So overnight a Khan and his family became poor, fully dependent on his subjects. A Khan was allowed only a small personal guard and enough cattle to sustain his family. This was a symbol of his surrender to his peoples’ interests and an insurance against his greed and corruption.

Now the newly elected Khan had to earn his peoples’ trust and find new wealth by taxations, or in war or by trade. Nomadic taxation system was called yasak/yasaq/jasaq (tribute), and it was rather simple: each tribal unit had to annually supply Khan with a certain amount of livestock or other goods, such as felt, leather, furs, ropes, tools, and etc.

A war-time marshal or Khan could request the tribes to provide their militia when needed. Each tribe would supply the requested amount of battle-ready warriors, fully equipped and armed. Each military unit consisted of kin warriors with their own elected leaders, and could act independently or as a part of a large unit. Under the martial law, all warriors were obliged to abide the marshal’s orders, and refusal to comply could be punished by death.

At the same time, the relatives of an executed warrior could openly complain after the martial law was lifted and question the marshal’s decision. If the marshal was found to exceed his powers, he would either pay the compensation fee per generally accepted rate, or could even be reelected. If the insulted party wasn’t happy with the ruling, they could take upon themselves to carry on bloody vendetta and seek to kill the said Khan or marshal, often successfully. The life of a nomadic Khan was dangerous.

In case of successful military raids or campaigns, the spoils of war were divided among the nomads honestly and democratically. The Khan would receive the biggest part, since he carried the most risks in case of a failure and because he had to feed his own guardsmen and their families. The tribal militia would receive parts of the spoils proportional to their quantitative input. Ideally, all of the participants would get their fair share, even if they didn’t play a decisive part in the overall success. But the honor and glory would go to those who did, and this is why everybody tried hard.

Judicial system

Courts didn’t exist in nomadic society in the same form as they did in SC nations. Instead, the nomads had arbitrary judges, who were among the most honorable and distinguished members of EN society. In order to become a judge, one must have had a life-long impeccable record of honest behavior and good judgement. If one didn’t meet these requirements, he simply would never see any clients, as they would choose to go to somebody with a better reputation.

If there was a dispute between two parties related to murder, theft, or pastures, and they couldn’t come to an agreement on their own, they could come to a judge they trusted, and he or she for a percentage of the settlement amount would listen to both sides, counsel them, and offer a solution to their dispute. If both parties were satisfied, the judge’s reputation grew, and he would find more clients.

But judges’ role wasn’t just to be arbiters for disputes. Best judges were so influential because of their practical wisdom that they became advisors to tribal leaders or even Khans. Some judges even were asked to take over the leadership of entire tribes or tribal confederations, which almost equaled them to the status of Khans. A status of a judge wasn’t passable to their children, it could only be earned by a person’s own merits and deeds. No wonder Ancient Greeks called the EN «the most decent of men».

In traditional ENC law, the criminal penalties never contained long-term imprisonment. In traditional society there were only two ways of dealing with criminals: material penalty and death. For each type of the crimes there was a universally agreed fee. Injuring a person cost a certain amount of cattle or money, killing a person would cost much more, and etc. And if, on rare occasions, the affected party didn’t accept the penalty for their killed member for some reason, they could choose «death for death» penalty instead. The execution of this sentence was up to the affected party, who would try hunting down and killing the violator.

Healthcare, education, and pensions

Of course, no society could exist without some form of healthcare system. The nomads never had hospitals, clinic, or medical schools. Instead, every nomads since the childhood was taught basic medical literacy. The parents were the doctors in their family, capable of curing most of the common ailments by themselves, using homemade remedies, such as sheep far, herbs, warms, horse milk, and etc.

In case if the disease was serious, they could visit or invite a tribal medicine man or a woman, who was a person of particular aptitude and knowledge in curing people. There were a few types of these nomadic «doctors», some specializing in herbal medicine, others in injuries and surgeons, some could fix broken bones and dislocations, and correct skeletal problems, and some could even cure the non-physical and mental illnesses, similar to shamans. These skills could be passed from generation to generation.

It must be noted that historically the EN were very healthy, comparing to the SC nations, as it was noted by European and Russian travelers in Modern Era who visited the nomadic tribes of Kazakhstan and Mongolia. They reported that the nomads don’t have any diseases, except for those caused by traumas, poisonous bites, infections, or age. Therefore, the traditional EN medicine was mostly geared towards treating these conditions.

The EN did not have formal education institutions with proper courses, syllabuses, and degrees. Instead, the entire adult population of the Great Eurasian Steppe was faculty, and all of the youth were students. The process of education took place «on the job» as the children grew older, learned new skills and with their increasing knowledge could take up on more responsibilities.

In day time adult nomads taught their youth practical skills: feeding, watching after, and milking the cattle; sewing, weaving, fixing clothes, making household objects; as well as riding horses, shooting bows and fighting with and without weapons. And by night the most knowledgeable adults would tell their children amazing educational stories of the past, fairy tales with moral twists, or share common knowledge in geography, natural sciences, math, astronomy, and etc.

The EN never had pensions or social security systems. Instead, their elders relied on help of their children. Basically, it was universally accepted that if parents did a good job raising their children, left them good material inheritance, brought them up as good, decent people, and taught them to fend for themselves, then they would be automatically rewarded by having a secured golden age, provided by their offspring.

At the same time the elders weren’t useless dead weight enjoying a free ride. They were busy till their last breath: they picked up the slack after busy and inexperienced young parents in rearing and educating their grandchildren and helping with the house chores. The elders usually lived with the youngest son till their death, and in return he inherited all their main estate, including the emblematic father’s yurt.

The nomadic elders were actively involved in social life: advised the active adult population on matters of Kóshes and wars, formed an elderly assembly called aq-saqaldar (the white beards) which was so vital that for many common questions people went directly to them first for answers. Very often the aq-saqaldar were able resolve small disputes, consul the couples, convince youth to avoid making rushed decisions, and even prevent inter-tribal conflicts. At the same time, their voice could be decisive in times of wars and conflicts, and make adult population take weapons in their hands.

The social status of elders was elevated and they played a significant integral part in EN societies in all times.

Distribution of wealth and religions

One of the most interesting and incredible features of the EN society was the absence of sharp stratification and the poor.

The former was due to a fact that every man and woman were warriors and had a right to defend their honor with weapons in their hands. This was a society of free men and women after all. And they could unite and protect their rights quite remarkably, so any leader would have to think twice before trying to instill unjust ruling. And in case if the disagreed party was too small to use force, they could simply pack their yurts and kósh to another place or join another leader to avoid exploitation.

The absence of poor was because the nomadic lifestyle is only possible with a certain minimal amount of wealth. As minimal requirement, any nomadic family needs a yurt or two, a certain amount of horses and camels to carry the people, their yurts and possessions from one seasonal camp to another, and, of course, enough meat cattle to sustain the entire family with nutrition.

If a nomadic family had lost their cattle, horses, camels, and yurt, it automatically meant that they are no longer fit to carry on with the nomadic lifestyle. Hence they became jataqs, which literally translates as «lying in one place» meaning that a person or a family became settled. Other nomads looked down at these unfortunates, who would dream of ways to acquire the necessary amount of nomadic wealth to get back into nomadic game. Clearly, falling as low as to become jataq and lose the status of a free nomad was considered one of the worst misfortunes that any nomad could think of.

The Eurasian Nomads had interesting attitude towards religions. Here is an incomplete list of just a few religions that various groups of EN have practiced during different periods of time: many forms of Shamanism, Vedic religions, Tengrism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism. That’s pretty much every single Afro-EuroAsian religion.

The main and original religions of the EN were Shamanism, Paganism, and Tengrism. The proper term that I prefer to use is natural philosophy, because the nomads worshiped what they perceived as essences, entities, substances of surrounding nature: the Sky, Earth, and Water (Tanir, Jer/Yer, and Su), and the spirits of nature or certain geographic location.

These beliefs were consistent throughout the entire existence of the ENC and was never fully replaced even after the nomads adopted other religions. The EN «priesthood» was rather basic and permeated the entire nomadic society: all regular parents were considered «family shamans» and could conduct common ceremonies and rituals; for special occasions there were «specialist shamans» who devoted their lives to spirits; the tribal leadership and Khans sometimes had their own «court shamans» whom they consulted on political and personal matters.

At the same time, the nomads almost never waged on any religious wars. Quite opposite, for the most part the EN were extremely tolerant towards all religions and faiths. They never allowed the differences in beliefs or rituals obstruct the common humane values.

When the nomads forged their mighty empires by the edges of their sabers, they almost never persecuted any religious groups, nor have they tried to force everybody into some one religion. Instead they allowed all subjects practice their own. Their motto was: just obey the law, send the troops, and pay the taxes, and nobody will bother you.

Women’s role in EN society

The shift from the Matriarchy to Patriarchy, which happened in the majority of the SC nations world-wide after the Agrarian Revolution, lead to an ever-decreasing social role and status of women. Within a couple of thousand years women went from worshiped Goddesses of Fertility and Nature to their lowest point in the medieval Witch Hunt, when women were openly discriminated, demonized, and prosecuted.

None of that ever happened to such extend within the ENC. Traditional role of women in EN society was the highest in human history during the Patriarchal Era. For a long time the nomads didn’t even fully transfer to the Patriarchal model. The Ancient Greeks wrote that the Scythian men and women had equal status. And traces of that equality survived to this day in most of post-EN societies.

Most scholars of today agree that the mythical nation of Amazon women who were fierce fighters and could best all-male armies was, in fact, based on the historical tradition of the ENC female warriors. The phenomenon of historical Amazons existed in the EN societies throughout the entire history.

There are famous female queens in the Saka society in the first millennium BC, such as Tomiris, Amaga, Zarina, and others. They were more than just administrative leaders: nomadic queens were required to assume military leadership roles just as male leaders. So powerful were these queens, that their status regarded as high as the famous SC rulers’ of the period, such as the Persian Achaemenid king Cyrus and the Macedonian Alexander the Great.

In my nation of Kazakhstan and neighboring Karakalpakistan there still exist a tale of Qyryq Qyz (forty maidens) who fought their way and saved their country from invaders. There are historical records of famous female military leaders among the Kazakh women in the past few centuries who fought along their men with invading Zunghars, Persians, Uzbeks, Manchu, and Russian.

The nomadic women were so strong and independent, that a courting ritual actually included a real wrestling match or a full-scale duel between the bride-to-be and the contender bridegroom. This wasn’t just an orderly bridal ritual: it was a real fight, and if a man lost, which happened sometimes, he would either become a lady’s slave, or would have to pay a ransom to free himself from the prisoner’s status. Not to mention that his honor would be permanently stained, because there were not secrets in the Great Eurasian Steppe.

By the Middle Age the Patriarchal trend has gradually reached the Eurasian Nomads and most rulers were male. However, even then the women remained influential in politics, and basically acted as gray cardinals, directing their royal husbands from behind the scenes. Great nomadic leaders like Genghis-Khan had multiple wives, but their position was different from that of the Islamic or Chinese harems. In the harems, the wives were basically living in one palace, with a strict hierarchy of senior, middle tier, and junior wives, and the eunuch who were serving/supervising them.

In EN society, each of wives had her own nomadic Aul consisting of a few or more yurts, cattle herds, herdsmen and servants, and sometimes even her own guards. Basically, each of wives had her own small nomadic state within a state, where she was a full master. Even in less rich families with two or more wives being a part of one Aul with shared cattle, each of wives had her own yurt where she lived with her children, and other wives had no direct control over her possessions.

But even in the middle ages sometimes noble women forwent the behind-the-scenes routine and ruler openly. This happened more than once in the so-called Mongol Empire. One of the ancestor of Mongols is Alan-Gua, a mythical pra-mother. In Genghis-Khan’s own life there was an array of important women: his mother Hoelun, his first and senior wife Borte, his relative Altani who received the title of Baatar for being a brave warrior, his junior wives, sisters Yesugen and Yesui, among many others. They played significant roles at certain moment during the forging of empire. Finally, the wife of his third son, the Great Khan Ögedei, named Töregene Khatun was a direct ruler of the empire for a few years until her son Güyük Khan became the next Great Khan.

The Patriarchy never reached the same heights in the Great Steppe as it did in Europe, Middle East, Central Asia, or China. Even in the 19th century, after the majority of the Eurasian Nomads were converted to Islam, the status of women remained comparatively high. Even when under the Islamic law, nomadic women never wore full-veil or were as separated from men as they were in the SC Islamic nations.

The high social status of women in the ENC could be traced from the religious beliefs. In the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age times, the female goddesses were treated as equal to male gods. A good chunk of Scythian/Saka pantheon is made of female deities. Many of them lost their prominence, but one goddess name have survived till today and is still regarded among the Kazakhs: the Goddess Umai. She was one of the highest-ranking ancient goddesses of fertility, matron of all mothers and wives. Some modern-day Kazakhs still conduct millennia-old Umai rituals when the new babies arrive.

Another sign of equality between men and women in the nomadic society is in the very base of all Turkic languages. There are about half a hundred live and extinct Turkic languages, but they all share the same feature: there are no words for «he» or «she» in all of them. Instead, all Turkic languages refer to persons of both genders equally as «ol» or «o». If a Turkic-speaking person wants to specify gender of a person, he or she just have to use words «this/that man» (mynau/anau erkek) or «this/that woman» (mynau/anau qatyn). This is a major detail that tells us a lot about how the nomads traditionally viewed men and women.

Traditional nomadic family

The Eurasian Nomads managed to keep and preserve a very old human social construct known as Tribalism which traces back to late Stone Age and Bronze Age. In a simplified form, the EN tribes (Taipa) consisted of smaller units, such as family clans (Ru), which in turn were formed by families (Otbasy, Janúya). A few of Otbasy would form an extended family that physically manifested itself in a form of a nomadic village called Aul.

Of course, extended families in EN societies were much larger than those of the SC nations, and could incorporate dozens or even hundreds of people. That is because the meaning of the word «blood relatives» included the genetic kin up to seven generations back, a principle knows as Jety Ata (Seven Male Ancestors).

The nuclear families, consisting of primary parents and their biological children, could also include adopted relatives’ children, older parents, or other relatives. These nuclear families were parts of extended families, which included siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles, once-removed relatives, twice-removed relatives, and fourth-generation relatives, and so on till seventh-generation relatives, both on paternal and maternal sides, as well as the children and relatives of father’s other wives (polygyny).

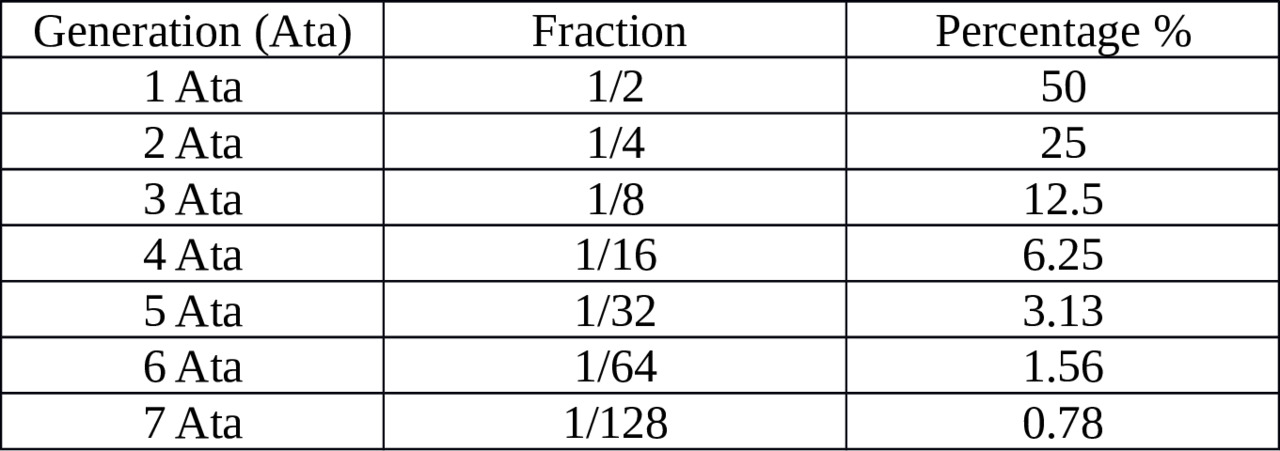

The marriages within these seven paternal generations were strictly prohibited to avoid interbreeding. Why seven? Since we’ve learned about genes in 20—21st centuries, some calculated that the chances of genetic mutations due to interbreeding decrease every passing generation, as shown in a table below. Back down seven generations, and the risk of it becomes as low as between 0 to 1%. How did my ancestors figured out the exact amount of generations of Y-chromosome needed to weed out the risk of genetic mutations? I don’t know exactly. But this explains why the nomads had superior genes and were famous for their health and endurance.

The extended families of seven-generation relatives could be as large as a few dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of members, because of the added polygynic families. A few of such extended families, formed a clan (Ru). A few dozens or hundreds of clans, still considered related, would belong to a single tribe (Taipa), usually all stemming from the same ancestor. Sometimes new Rus could be added either through marriage or war, or for political reasons.

Most of possessions and wealth within EN families were shared, including livestock, yurts, equipment, weapons, and etc. The notion of private property was weak. A friend or relative could ask for pretty much anything, and it was considered impolite to refuse. Even to this day some of the post-EN nations are known for their generosity and selflessness.

At the same time, the families, clans, and tribes were sensitive about matters of honor, therefore, insulting, injuring, or killing a member of another tribe, even not a very important one, would be considered an assault on the entire clan or even a tribe, and the revenge would follow. Sometimes it led to lengthy bloody vendettas that lasted for generations. But this was a good crime preventing policy in a nearly-stateless society, for one had to think twice before doing something bad.