Бесплатный фрагмент - Archaic roots of traditional culture of the the Russian North

(Collection of scientific articles)

Svetlana Vasilievna Zharnikova

Introduction

One of the most important tasks set by the time for cultural workers is the task of restoring national identity, self-respect of the people. The solution to this problem is impossible without the study, restoration and propaganda of folk culture, the system of value orientations that took shape among the people during the millennia of its historical existence. In this regard, the problem of identifying the deep roots of the North Russian folk culture is extremely acute today. One of the main issues is the issue of temporal stratigraphy in connection with the latest data of paleo-climatology, paleo-anthropology, linguistics, and archaeology. So, at present, thanks to the discoveries of paleo-climatologists, the time frame of the period of the initial development of the territories of the Center and the North of the European part of Russia is being revised. It is assumed that already in the Mikulinsky inter-glacial epoch (130—70 thousand years ago), when the average winter temperatures were 8—12 degrees higher than at present, and the climate in a significant part of the Russian Plain up to the northern regions was identical to the modern climate of the Atlantic regions of Western Europe, human collectives came to the coast of the White and Barents Seas. During the ice-free Valdai period (70—24 thousand years ago), people with a sufficiently developed level of cultural traditions continue to inhabit the territory of the Center and North of Eastern Europe, as evidenced by the burials of the Sungir in the Vladimir region and the Mezinskaya Upper Paleolithic site in the Chernigov region (25—23 thousand BC). During the glacial Valdai (20—18 thousand years ago), as it has now been found out, by no means all the territories of the Russian Plain (in particular, the Russian North) were covered with a glacier, since its extreme eastern border ran along the Molosh-Sheksninsky boundary… Thus, to the east of this border (up to the Urals), mixed spruce-birch and birch-pine forests and meadow grass steppes, that is, territories suitable for human life, were distributed.

In the Mesolithic era (10—5 thousand BC), a period of warming begins in the vast expanses of the European North, and by the 7th millennium BC. here the average summer temperatures are 4—5 degrees higher than the modern ones, and the zone of mixed broad-leaved forests is advancing almost 550 km north of the modern border of its distribution. On the territory of the Vologda Oblast, the investigations of S. V. Oshibkina revealed a large number of monuments of the Mesolithic era. Anthropologically, the people buried in the burial grounds of this time are classical Caucasians without the slightest admixture of Mongoloid.

During this period, no movements of the population from the territory of the Urals and Trans-Urals (the zone of formation of the Finns-Ugric tribes) were revealed.

Similar conclusions were made by D. A. Krainov for the Neolithic era.

Similar shifts seem unlikely in the Bronze Age, when the movement of the population to the north of Eastern Europe is recorded, as a rule, from the lands of the Dnieper region, the Middle Volga region and the Volga-Ok interfluve.

Analyzing today the numerous finds of the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze ages in the territories of the Center and North of the European part of Russia, we can assume with a considerable degree of confidence that up to the end of the Bronze Age (the end of the 2nd millennium BC) here lived tribes of Caucasians belonging to the Indo-European linguistic community. Already in the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze eras, a whole complex of ritual and mythological structures was formed in the Russian North, which in various transformed and often extremely archaic forms was preserved in the context of folk culture up to the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries and even up to now. These are ritual texts, a drawing of ritual dances, an ornament-amulet, etc. It is no coincidence that researchers believe that in Russian folk culture, elements have been preserved that are more archaic than not only ancient Greek ones, but also those recorded in the Vedas.

Thus, the previously accepted paradigm of the historical development of the European North of Russia, which asserted that these territories, starting from the post-glacial period, were populated by Finns-Ugric tribes who came from beyond the Urals (as a result of the pressure of the population surplus), which until the arrival of the Slavs here at the turn of 1—2 thous had a hunting-gatherer and fishing type of economy, is currently being revised.

The new paradigm seems to be as follows: according to modern data of paleo-climatology, anthropology, linguistics, ethnography and other related sciences, at the time of the arrival of the Slavs, the descendants of the ancient Indo-European population lived mainly in the territories of the European North of Russia, preserving the most archaic general Indo-European cultural traditions, an archaic type of lexicon and an archaic archaic a type. Their contact and mutual influence with the Slavic groups advancing into these territories was facilitated by the presence of a similarity of language, anthropological type and many cultural traditions, inherited by both of them from their common Indo-European ancestors.

Eastern Europe as the native land of Indo-Europeans

Among the many legends preserved by the memory of mankind, the ancient Indian epic Mahabharata is considered the greatest monument of culture, science and history of the ancestors of all Indo-European peoples. Initially, it was a story about the civil strife of the Kuru peoples, who lived more than 5 thousand years ago between the Ganges and Indus. Gradually new ones were added to the main text — and the Mahabharata came to us containing almost 200 thousand lines in 18 books. In one of them, called «Forest», sacred sources are described — the rivers and lakes of the country of ancient Aryans, that is, the land on which the events told in the epic unfolded.

But speaking of this country, called Bharata, we note that the final event of the narrative was the grand battle at Kurukshetra in 3102 BC. However, according to science, Aryan tribes in Iran and Hindustan did not exist at that time, and they lived in their ancestral home — far enough from India and Iran.

Where was she where all these grandiose events were unfolding? This question worried researchers back in the last century. In the mid-19th century, the idea was expressed that the territory of Eastern Europe was such an ancestral home. In the middle of the 20th century, the German scientist Scherer returned to the idea that the ancestral home of all Indo-Europeans was on the lands of Russia.

As known, the great river of our country — the Volga up to the 2nd century AD bore the name by which the holy book of the Zoroastrians of the Avesta — Ranha or Ra — knew her. But the Ranha Avesta is the Ganges of the Rigveda and Mahabharata.

According to Avesta, on the shores of the sea of Voorukasha (the «Milk Sea» of the Mahabharata) and Ranha (Volga) there were a number of Aryan countries — from Aryan-Wedge in the far north to seven Indian countries in the south, beyond Ranha.

The same seven countries are mentioned in the Rigveda and Mahabharata as the land between the Ganges and the Yamuna, on Kuruksetra. They are said about them: «The glorified Kurukshetra. All living beings, one has only to go there, get 7 rid of sins,» or «Kurukshetra — the holy Altar of Brahma; there are holy brahmanas-sages. Those who settled on Kurukshetra will never recognize sorrows».

The question naturally arises: so what kind of rivers are the Ganges and the Yamuna, between which the country of Brahma lay? We have already found out that the Ranha Ganga is the Volga. But ancient Indian traditions call the Yamuna the only large tributary of the Ganges, flowing from the southwest. Let’s look at the map and it will immediately become clear that the ancient Yamuna is our Eye!

Is it possible? Apparently — it is possible. It is no accident that during the Oka River, here and there, rivers with names comes across: Yamna, Yam, Ima, and Imyev. And moreover, according to Aryan texts, the second name of the Yamuna River was Kala. So, still the mouth of the Oka is called by the locals the mouth of the Kala. In addition, the Yamuna in the middle reaches was called Vaka, and the Oka River is also called in the Ryazan Region.

Other major rivers are mentioned in the Rigveda and Mahabharata. So not far from the source of the Yamuna (Oka) was located the source of the Sindhu River flowing east and south and flowing into the Red Sea (Red Sea) in Sanskrit — stream, sea). Recall that in the Irish and Russian annals the Black Sea was called the Cheremny, that is, the Red. So by the way, a section of its water area in the north is still called. On the shore of this sea, the Sind people lived and the city of Sind (modern Anapa) was located. It can be assumed that the Sindhu of the ancient Aryan texts is Don, whose sources are not far from the source of the Oka.

Moreover, in the postdeantic and Roman texts, Don is sometimes called Sind.

In the Volga-Oksk interfluve there are many rivers over whose names millennia have not been dominated.

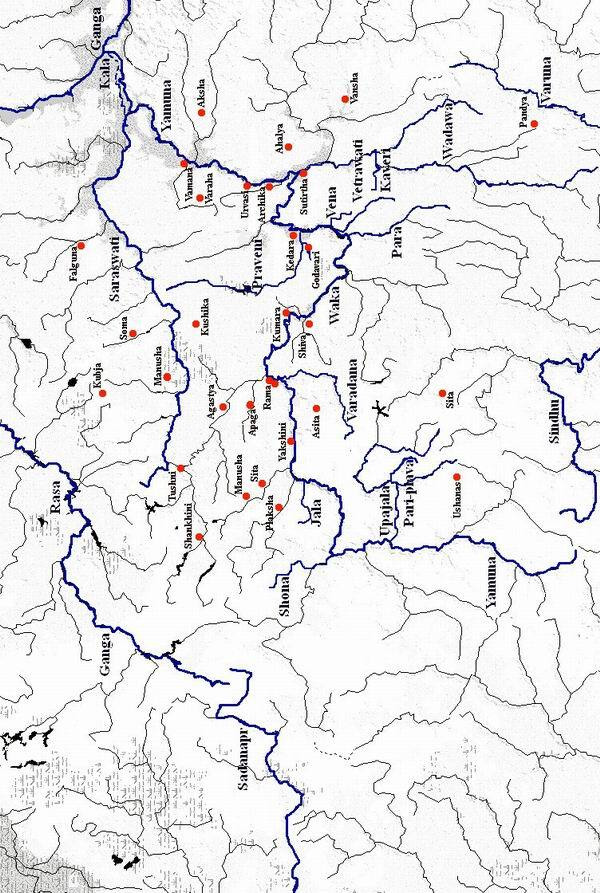

To prove this, no special effort is required: it is enough to compare the names of the Pochye Rivers with the names of the «sacred krinits» of Mahabharata, more precisely, that part of it, which is known as the «Walking through the Krinitsa». It is in it that a description of more than 200 sacred reservoirs of the ancient Aryan land of Bharat in the basins of the Ganges and the Yamuna (as of 3150 BC) is given:

Krinitsa — River in the Oka River Basin

Agastya — Agashka

Aksha — Aksha

Apaga — Apaka

Archika — Archikov

Asita — Asata

Ahalya — Akhalenka

Wadawa — Wad

Vamana — Vamna

Vansha — Vansha

Varaha — Varah

Varadana — Varaduna

Kaveri — Kaverka

Kedara — Kidra

Kubja — Kubja

Kumara — Kumarevka

Kushika — Kushka

Manusha — Manushinskoy

Pari-plava — Plava and Plavitsa

Plaksha — Plaksa

Rama (Lake) — Rama (Lake)

Sita — Siti

Soma — Somi

Sutirtha — Suterki

Tushni — Tushina

Urvasi — Urvanovsky

Ushanas — Ushanets

Shankhini — Shankini

Shona — Shana

Shiva — Shivskaya

Yakshini — Yakshina

It is also surprising that we are dealing not only with the almost literal coincidence of the names of the sacred krinits of the Mahabharata and the rivers of Central Russia, but even with the correspondence of their relative position. So, in Sanskrit and in Russian, words with the initial «F» are extremely rare: from the list of Mahabharata Rivers, only one has an «F» at the beginning of the name — Falguna, which flows into Sarasvati. But according to ancient Aryan texts, Saraswati is the only big river, flowing north of the Yamuna and south of the Ganges and flowing into the Yamuna at its mouth. Only the river Klyazma located to the north of the Oka and south of the Volga corresponds to it. And what? Among hundreds of its tributaries, only one bears a name beginning with

«F» — Falyugin! Despite 5 thousand years, this unusual name practically has not changed.

Another example. According to the Mahabharata, south of the sanctified Kamyaka forest, the river Praveni flowed into the Yamuna (that is, the Pra River), with Lake Godavari (where «vara» is a Sanskrit circle). What about today? As before, south of the Vladimir forests, the Pra River flows into the Oka River and Lake Gode lies.

Or another example. Mahabharata tells how the sage Kaushika during the drought flooded the river Paru, renamed for it in his honor. But further the epic reports that the ungrateful locals still call the river Para and it flows from the south to the Yamuna (Oka). And what? The river Para still flows from the south to the Oka River and, like many thousands of years ago, the locals call it.

In the description of the krynitsa five thousand years ago, it is said, for example, about the Pandya River, flowing near the Varuna River, a tributary of Sindh (Don). But the Panda River today flows into the largest tributary of the Don — the Vorona River.

Describing the pilgrims path, the Mahabharata reports: «There is Jala and Upajala, the rivers flowing into the Yamuna.» Is there now anywhere nears the Jala River («jala — the river in Sanskrit) and Upa-jala?

There is. This is the Jala (Tarusa) river and the Upa River, flowing nearby into the Oka.

It was in Mahabharat that the first mentioned west of the upper Ganges (Volga), the Sadanapru River (Great Danapr) — Dnieper.

But if the names of the rivers have been preserved, if the language of the population has been preserved, then the peoples themselves must probably be 10 preserved? And, indeed, they are. Thus, the Mahabharata says that to the north of the country of Pandya, lying on the banks of Varuna is the country of Martiev.

But it is to the north of Panda and Crow on the banks of Moksha and Sura that the land of Mordva (Mortva of the Middle Ages) lays Finnish-Ugric speaking people with a huge number of Russian, Iranian and Sanskrit words.

The country between the rivers Yamuna, Sindh, Upadzhala and Para was called A-Vanti. Exactly so — Vantit (A-Vantit) called the land of Vyatich between the Oka, Don, Upoya and Para rivers Arab travelers and Byzantine chronicles.

Mahabharata and Rigveda mention the people of Kuru and Kuruksetra.

Kurukshetra — literally, «Kursk Field», and it is in the center of it that the city of Kursk stands, where the «Word of Igor’s Campaign» places the Kursk — noble warriors.

An ally of the Kauravas in the Great War with the Pandavas was the Sauvir people living in the country of Sindhu. But just like that — with Sauvirs up until the 15th century, they called Russians — Saveryans. This people is mentioned — the Sauvirs and Ptolemy in the 2nd century.

The Rigveda reports the warlike people of Krivi. But Latvians and Lithuanians call all Russians that way — «Krivi», by the name of the neighboring Krivichi ethnic group, whose cities were Smolensk, Polotsk, Pskov, and today’s Tartu and Riga.

Speaking about the history of Eastern Europe, archaeologists and historians in general, the period from 10 to 3 thousand BC not particularly detailed. This is Mesolithic-Neolithic, with their archaeological cultures.

But the archaeological culture in a certain sense is abstract, but real people lived here, who were born and died, loved and suffered, fought and were related, and somehow they evaluated themselves, their lives, they called themselves by some specific names. That past, far from us, was present for them. And it is the ancient Aryan sources that make it possible to shed light on some of the dark pages of these seven millennia (from 10 to 3 thousand BC).

One of the tales of Mahabharata tells: «We heard that when Samvarana, the son of Raksha, ruled the land, great disasters came for the subjects. And then, from all kinds of calamities, the kingdom was destroyed, struck by hunger and death, drought and disease. And the enemy troops defeated the descendants of Bharat. And, causing the earth to shake on their own, consisting of four types of troops, the king of the Panchals quickly passed through the whole country, conquering her. And with ten armies, he won the battle of that.

Then the king of Samvaran, along with his wife, advisers, sons and relatives, fled in great fear. And he began to live by the great river Sindhu (Don) in a grove located near a mountain and washed by a river. So the descendants of Bharata lived for a long time, settled in a fortress. And when they lived there for a thousand years, the great sage Vasistha visited the descendants of Bharat. And when he lived there for the eighth year, the king himself turned to him: «Be our house priest, for we seek the kingdom.» And Vasistha gave his consent to the descendants of Bharata. Further, we know that he appointed the descendant of Puru the autocratic king over all the ksatriyas (warriors), throughout the earth.

And he again took possession of the capital, which was previously inhabited by Bharat and made all the kings pay him tribute. The powerful lord of the country Ajamidha, having taken possession of the whole earth, then made sacrifices.»

This is what Mahabharata tells about the affairs of days gone by. But when and where did this happen?

The reign of Samvaran refers, according to the chronology adapted in the Mahabharata, to 6.4 thousand BC. Then, after defeat and exile, the people of Samvarana live in the basin of the Don River in the fortress of Ajamidha for a thousand years, up to 5.4 thousand BC. All this millennium in their native lands is dominated by other conquering people and alien’s panchals. But after 5.4thousand BC the kauravas conquer their homeland from the Panchals and again live on it.

It would seem that the veracity of this ancient tradition cannot be confirmed or refuted these days.

But this is what modern archaeological science tells us. L.V. Koltsov writes: «Butovo culture was one of the major cultural manifestations in the Mesolithic of the Volga-Oka interfluve. The localization of the described monuments of Butovo culture in the western part of the Volga-Oka interfluve is noteworthy. The absolute chronology of the early stages of the Butovo culture is determined by the framework from the middle of the 8th millennium BC until the second half of the 7th millennium BC» (this is the time of the reign of King Samvarana — 6400 BC).»

In the second half of the 7th millennium BC another group of the Mesolithic population invades the Volga-Oka interfluve which is located in this region, in its western part, leaving an archaeological culture that we call Yenevsky.

With the advent of aliens, the population of Butovo culture first departs to the east and south of the region. Under the pressure of the Yenev culture, the Butovo population probably split into several isolated groups.

Some of them, apparently, even left the Volga-Oka basin, as evidenced by the facts of the appearance of typically Butov elements in other neighboring regions. Such are the monuments with Butovo elements in the Sukhona basin or the Borovichi site in the Novgorod region.«As for the Jenevites, their origin seems to archaeologists» is not entirely clear“. They note that: „Apparently, somewhere in the second half of the boreal period (6.5 thousand BC), part of the population of the Upper Dnieper moved to the northeast and settled part of the Volga-Oka interfluve, ousting Butovo tribes.

But «the isolation of the Yenevsky population, lack of peaceful contacts with surrounding cultures, ultimately led to a decline in culture and its reverse crowding out by strong Butovites. Thus, at the end of 6 thousand BC «the Late Butov population again begins to «reconquista "- the re-seizure of its original territory».

So, «Yenev culture, hostile to Butovo and having lost touch with the «mother» territory, apparently degenerated which subsequently led to facilitating the movement of Butovites back west and their assimilation of the remnants of the Yenevites. In any case, in the early Neolithic Upper Volga culture, formed in the region in the 5th millennium BC, we almost no longer find elements of the Yeni culture. Butovo elements dominate sharply.

When comparing the text of the epic and the data of archeology, the coincidence of both the chronology of the entire event and its individual episodes is striking. And a logical question arises: whether the descendants of the Puru-paurava are hiding behind the Butovites, and behind the «Yenevites» — their enemies are panchals?

Especially since it’s not strange but over these events time was not dominant.

And today, at the source of the Don (by the river Donets), near the cities of Kimovsk and Epifan, on a hill stands a tiny village retained its ancient name — Ajamki. Maybe someday archaeologists will find here the ruins of the ancient fortress of King Samvarana — Ajamidha.

But in this case, we can assume that the names of other settlements of ancient Aryans have survived to this day.

So at the confluence of the Upa and Plava rivers is the city of Krapivna. But one of the books of Mahabharata tells about the city of Upaplava — the capital of the Matsyev people who lived in the kingdom of Virata. And the word «virata» in Sanskrit means — «bast plant, nettle».

The greatest of the seven sacred cities of the ancient Aryans was the city of Varanasi — the center of learning and the capital of the kingdom of Kashi, which is, «shining.» The epic claims that Varanasi was founded in antiquity, with the grandson of the great-ancestor of the people of Manu, who escaped from the flood. According to the astronomical chronology of Mahabharata, Varanasi as a capital existed already 12 thousand 300 years before our days. Its name is produced either from the word «monitor», which means «forest elephant» (mammoth), or from the name of the rivers Varana and Asi, on which this city stood, or it’s possible that it comes from the combination «vara-nas», which means «our circle (fortress)».

If you look at the banks of the Vorona River, then we will not see such a city there. However, we recall that until the 18th century the present Voronezh River was called the Great Vorona, was navigable and even more full-flowing of the upper Don. Today, the largest city in southern Russia, Voronezh, stands on this river. When it is founded, we do not have any exact data. Voronezh is mentioned both under 1177 and in 1237. It is believed that the fortress of Voronezh was restored in 1586. In the 17—18 centuries the city was wooden, about however, as far back as 1702, there were ruins of some stone structures in its line, called locals «kazarskie». Now in Voronezh there are at least, four ancient Russian fortifications. There are monuments of previous eras. But could Voronezh be ancient Varanasi?

This question should be answered positively.

Firstly, the very name Voronezh is closer to the ancient Aryan Varanasi (Varanashi), than modern Indian Ben-Ares (Ares city), especially since in the 16th century the fortress was called Voronets.

Secondly, the ancient Aryan epic indicates a number of geographical objects in the Varanasi region, absent in India. In addition to the Varana River (Great Vorona), the Asi, Kaveri, and Deval rivers flowed near Varanasi. But near Voronezh itself the rivers Usman, Kaverye, Devitsa still flow. Not far from Varanasi were the Vai-durya reservoir («durya» — a mountain) and the Deva-sabha Mountains («sabha — a hill). But even now, the Bai-Gora (Bai-mountain) river flows in the Voronezh and Lipetsk regions, and the hills south of Voronezh, near the Sosny and Don rivers, are called Devogorye (Devo-hill).

One of the books of Mahabharata speaks of Varanasi as a city in the region of Videha. But the epic country of Videha with the capital Mithila was located at the edge of the seven estuaries of the Ganges (Volga) and thousands of lotus lakes and as Sanskrit commentators thought, had nothing to do with the kingdom of 15 Kasha. (By the way, even now, many lotuses are growing in the Volga delta, and 5—6 thousand years ago, the level of the Caspian Sea was 20 meters lower than the modern one and the Volga delta merged with the deltas of the Terek and Ural rivers into one huge lake region). This apparent contradiction is simply explained.

At Voronezh, the Veduga River flows into Don, by whose name as it appears, and the region of Videha was named.

Near the city of Varanasi as Mahabharata testifies, the city of Khastin was located, which became the capital of the Aryans after the battle of Kurukshetra (Kursk Field) in 3102 BC. And what? Next to Voronezh is the village of Kostenki (a city in the 17th century), famous for its archaeological sites, the oldest of which date back to 30 thousand BC. The cultural layers of this village come from ancient times to our days without interruption, which indicates the succession of culture and population. So that, we think, it can be argued, that Voronezh and Varanasi, like Kostenki and Khastin, are one and the same.

On the Voronezh River there is also another large city in the south of Russia — Lipetsk. This name is not in the Mahabharata. But there is the city of Mathura (Matura), also one of the seven sacred cities of the ancient Aryans. It was located on Kurukshetra (Kursk field) east of the Yamuna (Oka). But even now, the Matyra River flows into the Voronezh River near Lipetsk. Epos says what to capture the city of Matura Krishna first had to master the five elevations in his vicinity. But today, like many thousands of years ago five hills north of Lipetsk continue to dominate the valley.

Quite possible, that numerous information on ethnogenesis, saved by Mahabharata, will help archaeologists in identifying those archaeological cultures of Eastern Europe, which bear their conditional archaeological names so far. So according to the Mahabharata, in 6, 5 thousand BC: «all these panchals are descended from Duhshanta and Paramestkhin». Thus, the emergence of a tribe or people is confirmed, called by archaeologists the «Jenevites,» immediately before their invasion of the Volga-Oka interfluve, because Duhshanta directly preceded Samvarana.

Once Gavrila Romanovich Derzhavin wrote: «The River of times in its aspiration takes away all the affairs of people.»

We are faced with an amazing paradox, when real rivers seemed to stop the flow of time, returning to our world those people who once lived along the banks of these rivers, and their affairs. They returned our Memory to us.

About the location of the sacred mountains Meru and Khary described in Indo-Iranian (Aryan) mythology

The location of the legendary Hara and Meru, the holy northern mountains of the Indo-Iranian (Aryan) epos and myths is one of the many riddles in Eurasian ancient history that has been troubling researchers for over a century and prompting ever more, sometimes totally contradictory, hypotheses. As a rule, they are believed to be the Scythian Ripei or Hyperborei mountains mentioned by the authors of antiquity. Over 80 years ago The Arctic Home in the Vedas, by the outstanding Indian political figure, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, launched a series of publications related to this subject in one way or another and continued to this day. The answer has never been found, as obvious from the two most recent publications — a book by G. Bongard-Levin and E. Grantovsky From Scythia to India (1983), The Ethnogeography of Scythia by I. Kuklina (1985). The two socalled Ripei Mountains locations, which the books propose, are mutually exclusive, though the authors proceed from the same ancient myths, historical sources and data.

Bongard-Levin and Grantovsky, analyzed the Avesta, Rigveda, Mahabharata, the works of Herodotus, Pomponius Mela, Plinius, Ptolemaeos, and the information provided by medieval Arabian travelers, ibn-Faldan, ibn-Batuta, and concluded that the geographical characteristics, repeated without exception in every source, are factual a/id indicate that the Ripei Mountains, Hara and Meru were the Urals, since only they possess nearly all the specific features attributed to the holy northern mountains: high altitude, natural resources, proximity to northern seas, etc.

Kuklina, the author of The Ethnogeography of Scythia, disagrees entirely, and argues that «it is apparently necessary to first distinguish the concept of the mythical northern mountains from that of mountains north of Scythia where many rivers began. Both of them were named Ripei. However there is no doubt that only the latter mountains can be localized, whereas the former, connected with the far north and Hyperborei, should be sought for in the myths of Indo-lranian peoples». Kuklina backs up her conclusions with a large number of comments by ancient authors — Pseudo Hippocrates, Dionisius, Eustaphius, Vergilius, Plinius, Herodotus, etc. — about the northern mountains called Ripei. She then cites, from Bongard-Levin and Grantovsky, examples of amazing similarities between Scythian polar concepts and ancient Indian and ancient Iranian «Arctic» tradition.

Kuklina draws the following conclusion: the northern mountains and the entire

«Arctic» cycle are merely a myth, a retelling of what was learned from native Siberians. She feels the Ripei Mountains were actually the Tien Shan Mountains, as they are the only latitudinal watershed range in this part of Eurasia, are very high, and are north of India and Iran, etc.

Here it is necessary to single out the following groups of information about the Ripei Mountains, Hara and Meru, identical in the writings of medieval Arab travelers, authors of antiquity, in Scythian and ancient Iranian mythological tradition. This information is also noted by the authors of From Scythia to India and the author of The Ethnography of Scythia.

1. The Ripei Mountains, Hara and Meru extended from the west to the east, separating north from south;

2. In the north, beyond the Ripei Mountains, Hara and Meru, is the Arctic or Kronian, or Dead or Milk Ocean, or the huge Vourukasha Sea that receives the rivers flowing from these mountains to the north;

3. The Ripei Mountains, Hara and Meru are a divide, as they separate rivers flowing to the south and flowing to the north;

4. From the summits of the Hara, Meru and Ripei Mountains, spring a) the heavenly Gang, b) holy Ratha, c) Rusiya River, d) all of Scythians big rivers except the Ister-Danube;

5. In these northern lands one can always see high in the sky the North Star and the Big Dipper;

6. The day there lasts half a year and the night half a year, and in the winter a cold northeast wind blows, causing much snow;

7. Rivers originating in these mountains have golden beds, and the mountains themselves contain countless riches;

8. The mountains are covered with forests, they abound with animals and birds and are very high and impassable;

A land of happiness lies beyond the Ripei Mountains, Hara and Meru.

Kuklina does not believe that the northern mountains were the Urals, and has reason to note essentially insurmountable contradictions: ancient writers indicate unequivocally that the Ripei Mountains extended latitudinal, which is not true of the Ural Mountains; the Ural Mountains are located to the east or northeast of Scythia which was in the Black Sea area, certainly not to the north; the Ural Mountains are not the divide from which Scythian rivers emerged.

It is hard to disagree with this. But while Kuklina finds contradictions in the hypothesis of the authors of From Scythia to India, she also faces practically irreconcilable contradictions. First, although the Tien Shan Mountains extend latitudinal, they are definuely not the divide of rivers flowing into northern and southern seas. True, the source of the great Syrdarya is in these mountains, but it flows into the Aral Sea which can hardly be called Lhe Arctic or Dead Ocean. As for the other rivers in Central Asia (those flowing to the north), none of them takes its waters to the sea, which does not in any way correspond to Indo-Iranian poetic mythical or Scythian tradition. Although the divide of Central Asian and Kashgarian rivers is in the Tien-Shan Mountains, those flowing south do not reach the sea, but are all tributaries of the lone Tarym River that disappears in the Takle-Makan desert, an unlikely place for rivers with golden beds, a six-month day and six-month night. The North Star and Big Dipper are not high in the sky, and many more things are lacking that apply specifically to the northern mountains. Thus, we are confronted with the paradox: the Urals are not the Ripei Mountains of the Scythians or the holy Hara and Meru of the Indo-Aryans, but neither does the Tien-Shan Range tally with the traditional descriptions. The author of The Etknogeography of Scythia believes that the Northern mountains were only a myth: ".there is no doubt about it that the Indo-Iranians did not live in areas near the Polar Circle but obtained realistic information about polar phenomena mixed with legends about the northern mountains (italics) and the gods from their northern neighbours.»

However, it is highly improbable that different peoples originated a myth with quite concrete geographical characteristics — length, latitudinal orientation, wind direction, long winter, northern lights, etc. — that were not based on reality. This is the entire stranger in view of the following circumstances: according to Mahabharata and Rigveda the country of Harivarsha was in the north and was the abode of Rudra-Hara. «The stylite with blond braids», the «holy sovereign Hari-Narayana, boundless Purusha, radiant eternal Vishnu, the brown bearded Ancestor of all creatures.» The north was the home of the god of wealth, Kubera, of the «seven Rishi» who were the sons of the creator Brahma. These brothers were revered as seven Prajapati — the «rulers of all creatures», the forefathers and ancestors embodied in the seven stars of the Big Dipper. The north was also the location of the «pure, wonderful, meek, desirable world» where «well-wijhing people are reborn», and in general «the northern part of the world, more beautiful and pure than any other,» and «the day of the gods» is the sun’s route to the north.

It seems Kuklina is far from correct when she asserts that the northern mountains of the Indo-Iranian epos were totally fictitious and that there is no point in looking for them on the map. However, it is also hard to agree with the authors who claim the Hara and Meru Mountains were the Urals; the concept holds too many contradictions.

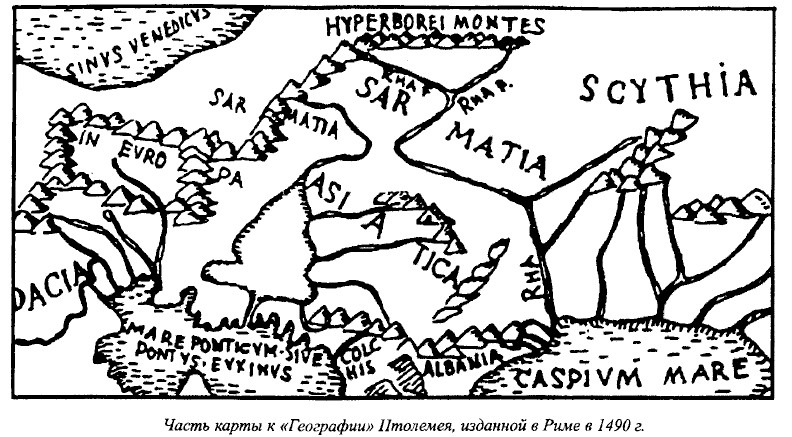

No doubt it is necessary to look once again at the ancient sources, especially since more and more researchers are convinced that the authors of antiquity must and should be believed. For instance, M. Agbunov, on the basis of paleo-graphic data on changes in the Black Sea coastline, concludes that «the works of ancient authors are, as a rule, a reliable source and merit more attention and trust… it should be stressed that most of the concrete historical and geographical descriptions by ancient authors are absolutely correct.» In this case we can use such an authoritative source as Ptolemaic» Geography, specially since it is referred to by the authors of From Scythia to India and the author of The Ethnogeography of Scythia.

But because the text, as we saw earlier, can be interpreted in different ways to prove contradictory conceptions, let us look at Ptolemaeos’ map, or rather at that part of Geography (published in Rome in 1490) where a mountain range is shown in the north and called Hyperborei Monies.

Part of the map of Geography by K. Ptolemy 1490

This was the part in Ptolemaeos’ work that Bongard-Levin and Grantovsky called a mistake, claiming that Ptolemaeos put non-existent mountains in the north.

When we compare the map of the European part of the Soviet Union with Ptolemaeos’ map, we can see genuine geographical sites such as the Baltic, Black, Azov and Caspian seas, and the Volga running into the Caspian and called Rha, (Called Ra by some authors) the ancient Avesta name. We also see all the more or less significant elevated areas up to the Southern Urals, which are separated by a considerable distance from the Hyperborei Montes that Ptolemaeos marked in the north and that extend latitudinally, and that are the starting point of two sources of the holy river of the ancient Iranians-Rahi. This map indicates that Ptolemaeos, and probably geographers of antiquity long before him, make a distinction between the Hyperborei and the Ripei mountains, and the Urals.

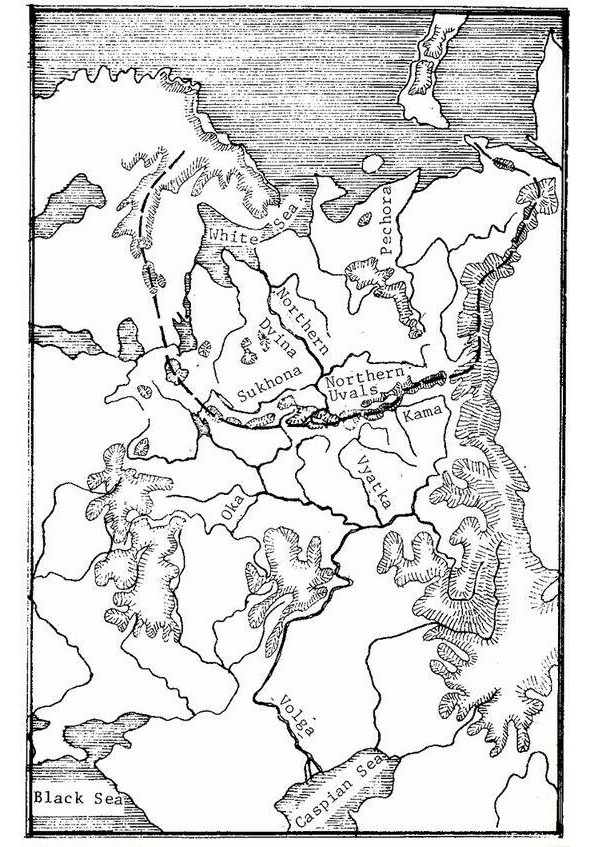

Was Ptolemaeos correct or incorrect, were there such elevations in the north that were the starting point of the Volga (Manu authors note that in ancient times people did not know the true source of the Volga. See V. M. Beilis. Al-Idrisi…) and Kama rivers? The map of the USSR shows objectively that there were such elevations-the Northern Urals (Hills). Located in the northeastern European part of the Soviet Union they extend 1,700 kilometers from west to east, and through the Timan mountain ridge combine into a single system with the Northern Urals (In Ptolemaeos Geographical Guidebook §5 gives the coordinates of the Hyperborei Monttanian in northen Europe (63—64° northern latitude), that is, the latitude of the Norhtern Urasls).

One of the Soviet Union’s most prominent geomorphologists, Yu. Meshcheryakov, wrote the following in his fundamental study, Relief of the USSR, published in 1972: «The world divide that borders the Arctic Ocean basin is farthest away from the ocean to the south, deep inside Eurasia, the Asian part of the USSR. The maximum distance from the ocean to the divide -3,000—3,500 kilometers — is marked on the meridians of Baikal-Yenisei… Going through the Urals, the dividing line suddenly approaches the coast, and with inike Northern Uvals it is only 600—800 kilometers from the shore». The author goes on to say that the Northern Uvals are the main divide of northern and southern seas in the Russian plains. While he calls them the «principal orthographically anomaly of the Russian plains», he notes the paradox that «the highest elevations (Middle Russia, Volga region) are in the southern part of the plains, they are not the main dividing lines, yielding the role to the insignificant, relatively small Northern Uvals.»

Meshcheryakov also points out that unlike most of the Russian plains’ elevations which are oriented meridianally, «The origin of the inverse morphostructure of the Northern Uvals remains unclear. This elevation does not have a meridianal, but a sub-latitudinal direction».

He writes of a «close, organic tie between’ the undulating deformations of the Urals and Russian plains,» and stresses that "...the Timan mountain ridge starts from the orographical junction of the «Three Rocks» (Konzhakovsky Rock- 1,569 meters, Kosvinsky Rock-1,519 meters and Denezhkin Rock- 1,492 meters). This wide and elevated section of the Urals is on the same latitude as the Northern Uvals and joins them forming a single latitudinal elevated zone». The work also notes the same origin of the Northern Uvals, Galichskaya and Gryazovetsko-Danilovskaya elevations, or those latitudinal elevations in the northeastern European part of the Soviet Union that unite into a single bulge the elevations of Karelia, the Northern Uvals and Northern Ural mountains, that is, the part of the range that runs in a north-northeastern direction.

Thus, the Northern Uvals — the main divide of northern and southern rivers, the basins of the White and Caspian seas — are the precise location Ptolemaeos cited for the Hyperborei (or Ripei) Mountains, the source of the holy river Rha.

However, according to the same Avesta tradition, its source is in the mountains of High Hara — Hara Berezaiti, on the «golden summit of Hukairya». Of interest in this connection is what Al-Idrisi (12th century) wrote about the Kukaiya Mountains that he places in the far northeast of the oecumene and «that could be connected with the Ripei Mountains noted by ancient geographers, primarily Ptolemaeos», and the Hukairya Mountains of Avesta. Dwelling on the Kukaiya Mountains, the source of the Rusiya River, Al-Idrisi points out that: «Six big rivers flow into the aforementioned Rusiya River; their sources are in the Kukaiya Mountains. These are big mountains extending from the Black Sea to the edge of the inhabited Earth… They are very big mountains; no one can climb them because of the extremely cold weather and the constant abundance of snow on their peaks.»

If we accept the Ripei (Hyperborei) and Kukaiya mountains as the Northern Uvals, the six rivers are readily found. The Volga (Rusiya) is indeed the drainage point of six rivers that flow from the Uvals — the Kama, Vyatka, Vetluga, Unzha, Kostroma and Sheksna (Yu. Meshcheryakov stresses the ancient origin of the river network at the divide).

Thus, if we regard the Kama as the source of the Volga, as was the case in ancient tradition, then the Volga (Rha) of Ptolemaeos and Avesta, indeed, begins in the Northern Uvals (especially since the actual sources of the Volga are in the Valdai elevation which is included in the southern part of the bulge described).

They are also the starting point of the biggest river in the Russian North -the great and deep Northern Dvina which runs into the White Sea and has over a thousand tributaries. One of them, the Emtsa River, does not freeze over in the winter due to the hot springs in its canyon.

The hymn of Ardvisura Anahita to the holy Avesta River has these lyrics:

«The large river, known afar, that is as large as the whole of the waters that run along the earth; that runs powerfully from the height Hukairya down to the sea Vouru-Kasha.

She, Ardvi Sura Anahita, who has a thousand cells and a thousand channels.

«From this river of mine alone flow all the waters that spread all over the seven Karshvares; this river of mine alone goes on bringing waters, both in summer and in winter. (Aban yast)

In exalting the holy river flowing to the north into the Vourukasha Sea, the author of the hymn gives praise to those who bring it offerings on the «Hara summit,» on the «Hukairya summit» of the ancestors of the Aryans, Jima (Yama) and Paradatta.

In addition, the latitude of the Northern Uvals is 60° north and they are not only the principal divide of the Russian plains and the border between north and south, but the year there is divided into six light and six dark months. The North Star and Big Dipper there are high in the sky, and if you go down toward the sea you can also see the northern lights. A long winter is normal on these latitudes where the first snow is often in the latter half of September, and the last snow can be at the end of May, so that «the average period of safe growth of plants is equal to four months».

Relevant here is Herodotus’ comment that «in all the countries named (by the Ripei Mountains) the winter is so harsh that hard frosts last eight months. During that time, even if you pour water on the ground there will be no mud, unless you light a fire… Such cold weather lasts in those countries an entire eight months, the other four months not being warm either».

Besides, it is interesting that the presence of hornless cattle in the Kirov and Perm districts confirms Herodotus’ comments about hornless bulls in the lands by the Ripei Mountains, which he believes is due to the harsh climate in these areas. (Report about hornless Perm cattle that give high-fat milk (4.7 percent) and fare well in frosts and With amounts of food).

Turning once again to Indo-Iranian epic tradition, we should stress one more interesting detail: the hymns of Avesta, Rigveda and Mahabharata, authors of antiquity, and medieval Arab travellers all speak of riches of the Hara and Meru, Ripei (Hyperborei), and Kukaiya Mountains. Herodotus writes: «There is apparently very much gold in northern Europe. I cannot say for sure how it is extracted. According to legend, one-eyed Arimaspi people steal it from griffins.»

Is there any truth to stories about gold in the river beds, the countless treasures of these mountains if we regard the Northern Uvals as the legendary mountains? Let us look at reference literature. The Brokhaus and Efron encyclopedia says that the banks and river beds of the Mera, Volga (by Kostroma), Unzha and their tributaries have such an abundance of pyrites (fool’s gold) that it is enough lor industrial use. At the end of the 19th century peasants collected rock-ore washed up by the rivers and brought them to local factories.

The Vurlam River flowing from the Northern Uvals to the south and its tributaries carry their waters through fields containing golden sand.

Relevant here is some information about the mineral resources of the Northern Uvals, the Timan mountain ridge, and other elevations in the northern European part of the Soviet Union. Many of them were most likely well known and used back in ancient times. They are sheet mica, mountain wax, tar, oilstone, rock salt, cuprous limestone, malachite, iron, copper, tin, silver, gold, precious stones such as diamond, zircon, ilmenite, spinel, amethyst, garnet, rock crystal, agate, beryl, chalcedony, amber, etc. This list could be continued, but suffices to prove that the rivers flowing in «golden beds» and mountains «rich in precious stones» are not myths.

The mysterious holy mountains of Indo-Iranian mythology, Scythian legends and stories by ancient writers, begin to seem quite real as virtually everything said about Hara and Meru, the Ripei (Hyperborei) mountains applies to the Northern Uvals:

1. Like the legendary mountains, the Uvals extend from west to east.

2. Like these mountains, they are the border of the north and south, and are the main divide of rivers of the south and north that flow from the Uvals.

3. As in these mountains, the North Star and Big Dipper can be seen high in the sky all year.

4. As true of these mountains, the shores of the freezing White and Barents seas

lie behind the Uvals. Here the polar day and the polar night are both half a year long. The northern lights can be seen on the sea shore.

5. There is only one place in the Soviet Union where the direction of the predominant air masses in the winter is clearly oriented from the northeast to the southwest. Starting out in the Kara Sea, running along the western extremity of the Northern Urals, and skimming over the Northern Uvals, this powerful current «is the same northeast wind invariably mentioned in connection with the Hyperborei and Ripei mountains and the related problems».

6. Rivers flowing from the Northern Uvals do often have gold in, their beds, or beds lined with pyrite (fool’s gold) which resembles gold.

7. The Northern Uvals and the Timan mountain ridge are rich in a variety of minerals.

8. The Northern Uvals are covered with luxuriant forests and an endless variety of herbs and grasses. Fir, linden, elm, alder, and birch trees, black and red currants, Cornelian cherries, honeysuckle, rose hips, and thickets of hop grow on their slopes. These places have always been famous for abundance of animals, birds and fish: all this is mentioned in ancient and medieval literature as applied to the Ripei Mountains.

Among what has been said of holy mountains in the Indo-Iranians (the Ripei Mountains of the Scythians), and what we have not as yet linked with the Northern Uvals, there is another important detail — their altitude. Indeed, the Hara, Meru and Ripei mountains are described as very high, whereas the Northern Uvals today are no ' more than 500 meters above sea level. But it must be kept in mind that the singers of Mahabharata always described Hara and Meru as covered with forests and teeming with animals and birds.

Consequently, they could not be very high.

Just what are the Northern Uvals like? Let us refer to E. Murzaev’s Dictionary of Folk Geographical Terms which says that an «Uval» (hill) in the vicinity of the White Sea is a steep and tall river bank, a mountainous ridge along a valley.

The river valleys of the Northern Uvals divide are deep and steep canyons with sides up to 80 and more meters high. The Sukhona drop on the section from Totma its month is over 49m, here it is as rapid as a mountain river.

We know the altitude of mountains is not stable — over the millennia elevation parameters change, they become bigger or smaller. According to geological data, the ancient river valleys of the divide were 80—160 meters lower than they are today. Researchers unanimously agree that deep-set ancient valleys were caused by vertical tectonic movements of relatively large amplitude — 200—400 m. Hence, we cannot say with certainty how high the Northern Uvals were 3,000—5,000 years ago, that is3 in Indo-Iranian antiquity, whose lower level it is impossible to chronologies precisely.

Finally, the question of cradle of the Indo-Iranian peoples is still open. Most Soviet researchers link the formation of the Indo-Iranian group with the southern half of the European part of the Soviet Union — the reaches of the lower Don. the northern Black Sea and Volga areas, etc. In antiquity the Uvals were indeed located north of the sources of rivers flowing on these lands, and they blocked the way to the shores of the White and Barents seas, which is probably why the legends said the mountains were impassable.

There is one more point: precisely in the watershed section of the Northern Uvals, to this day, there are many place names of intriguing similarity to Indo-Iranian words: Harino, Harovo, Harina Mountain, Harenskoye, Harinskaya, Harinovskaya; Mandara, Man-darovo, Mandra (and the Mandara mountain in the Mahabharata); Ripino, Ripinka, Ripa (and Ripei Mountains), etc. Just as interesting are river names in the region, names of still unknown origin: Indola, Indomanka, Indocap, Sindosh, Varna, Striga, Svaga, Svatka, Hvarze-nta, Harina, Pana, Kobra, Tora, Arza, etc. (To the best’ of the author’s knowledge the possible connection between the hydronyms of this area and Indo-Iranian languages has not yet been studied). Besides, as late as the early 20th century the weaving and embroidery designs used by Russian peasant women still preserved the tradition of geometric ornamentation which originated in the most ancient Eurasian cultures of the Copper and Bronze ages, and primarily in the ceramic ornamentation of the Andronovo farming-stock breeding culture of the 17th-12th centuries BC which many researchers believe was an Indo-Iranian (Aryan) group.

This gives reason to surmise that the holy mountains of Hara and Meru in Indo-Iranian mythology, the Hyperborei and Ripei Mountains mentioned by the Scythians and authors of antiquity, were the elevations of the northeastern European part of the Soviet Union — the Northern Uvals. In conclusion, the Northern Uvals, especially in their eastern and central regions, remain practically unexplored by archeologists. Hopefully, in the near future they can expect new and fascinating discoveries helping to raise the curtain covering the history of many peoples inhabiting our continent.

Notes

Tiiak B. The Arctic Home in the Vedas. Bombay. 1903.

Бонгард-Левин Г. М., Грантовский Э. А. От Скифии до Индии. Древние арии: мифы и история. М. 1983.

Куклина И. В. Этногеография Скифии по античным источникам. Л. 1985.

Геродот. История в девяти книгах. Л. Наука. 1972. Book IV, Book III.

Помпоний Мела. Землеописание. Вестник древней истории. 1949. №1.

Гай Плиний Старший. Естественная история. Вестник древней истории. 1949. №2.

Клавдий Птолемей. Географическое руководство. Вестник древней истории. 1948. №2. Латышев В. В. Известия древних писателей о Скифии и Кавказе.

Махабхарата. Выпуск V. Book I. Мокшадхарма. Перевод Б. Л. Смирнова. Ашхабад. 1983.

Агбунов М. В. Проблемы и перспективы изучения произведений античных авторов о Причерноморье. Древнейшие государства на территории СССР. М. 1984.

Мещеряков Ю. А. Рельеф СССР. М. 1972.

Ардвисур-Яшт, пер. И. Брагинского. Поэзия и проза Древнего Востока. М. 1973.

Бейлис В. М. Ал-Идриси (12 век) о Восточном Причерноморье и юго- восточной окраине русских земель. Древнейшие государства на территории СССР. М. 1984.

Минеев В. А., Малков В. М. Вологодская область. Вологда. 1958.

Коми-Пермяцкий автономный округ. М-Л. 1947.

Энциклопедический словарь. Изд. Брокгауза и Ефрона. СПб. 1895. T. 31.

Геологическое строение СССР. М. 1968.

Шишкин Н. И. Коми АССР. М. 1959.

Архангельская область. Архангельск. 1967.

Природа Вологодской области. Вологда. 1957.

Мурзаев Э. М. Словарь народных географических терминов. М. 1984.

Природные условия и ресурсы Вологодской области. Выпуск 2. Вологда. 1972.

Оранский И. М. Введение в иранскую филологию. М. 1960.

Дьяконов М. М. Очерки истории Древнего Ирана. М. 1961.

Тереножкин А. И. Предскифский период на Днепровском правобережье. Киев. 1961.

Горнунг Ю. В. К вопросу об образовании индоевропейской языковой общности. М. 1964.

Трубачев О. Н. Названия рек Правобережной Украины. М. 1968.

Грантовский Э. А. Ранняя история иранских племен Передней Азии. М. 1970.

Алексеева Т. И. Этногенез восточных славян по данным антропологии. М. 1973. Мерперт H. Я. Древнейшие скотоводы Волго-Уральского междуречья. М. 1974. Гусева Н. Р. Индуизм. М. 1977.

История Иранского государства и культуры. М. 1978.

Смирнов В. К., Кузьмина Е. Е. Происхождение индоиранцев в свете новейших археологических открытий. М. 1977.

Список населенных мест Вологодской губернии по сведениям 1859 г. СПб.1866.

Вологодская область. Вологда. 1974.

Кузьмина Е. Е. Происхождение индоиранцев в свете новейших археологических данных. Этнические проблемы истории Центральной Азии в древности. М. 1981.

Archaic motifs in North Russian folk embroidery and their parallels in ancient ornaments of Eurasian steep population

For some one hundred years now Russian folk embroideries have attracted closest notice. Towards the close of the 19th century several magnificent collections of such embroideries were assembled. Further, researches conducted by V. Stasov, S. Shakhovskaya, V. Sidamon-Eristova and N. Shabelskaya initiated the systematization and classification of the various types of ornamental designs in Russian folk embroidery. These same authors also made the first attempts to decipher the intricate narrative compositions so characteristic of folk tradition in Northern Russia.

The surging interest in the folk arts and crafts caused a series of notable studies to be devoted to analysis of the narrative and symbolical content, the specific techniques and the regional dissimilarities of Russian folk embroidery.

However, most authors concentrated on the anthropomorphic and zoomorphic representations and the archaic three-element compositions incorporating stylized and transmuted representations of, more often, female and, less often, male pre-Christian deities. It is this group of motifs that has always fascinated students. A somewhat specific group consists of the geometrized motifs of North Russian embroideries, which, as a rule, accompany the basic elaborated narrative compositions — although frequently such motifs are exclusive in the decoration of towels, sashes, skirt hems, and shirt and blouse sleeves and shoulder yokes, which explains their importance for art historians.

It should be noted that along with an analysis of the complex narrative designs, greatest note was paid by A. Ambroz in his well-known articles to the geometrical symbolism as archaic in Russian embroidery. Further, in her fundamental monograph published in 1978 G. Maslova extensively considered the evolution and transformation of geometrized ornamental motifs in terms of their historico-ethnographical parallels, which regrettably go no further back than the 10th-11th centuries.

B. Rybakov has always highlighted the archaic geometrized symbolism in Russian ornamental design. Thus, ever present in his writings of the 1960s and 1970s, 6 and, especially, in his 1981 treatise concerned with the paganism of the ancient Slavs is the point that the folk memory has preserved and carried through the ages in the ornamentation of embroidery, wood carving, and folk toys the profoundly ancient weltanschauungs rooted in the dust of the millennia.

Most fascinating in this respect are the collections of Northern Russia museums especially from places that had been populated by the Slavs in the 9th and 10th centuries prior to the Christianization of Russia. To all practical intents, there were no large ethnic units, there that spoke a different language, while the remoteness from the central states, the relatively peaceful existence (the North-Eastern part of Vologda Province was hardly ever ravaged by war), plus the dense forests and the isolation of many inhabited localities due to marshes and the absence of roads, all served to preserve patriarchal mores, and economies, and also ensured a jealous affection for ancestral beliefs, thus implying the preservation of the ancient symbolism as encoded in the ornamental motifs of embroidery.

Of particular interest are the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, embroideries deriving from the North-Eastern sections of Vologda province and the neighboring districts of Arkhangelsk province. Toponymical evidence shows that in those times these parts were hardly populated at all by Finno-Ugric tribes. Most of the names are of a Slavonic origin and furthermore most are extremely ancient, as for instance, Dubrava (which means forest). Thus, of 137 localities in the Tarnoga district of the Vologda region only six have distinctly Finns-Ugric names. We may hence presume that at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries the population here was comprised of direct descendants of those Slavonic (Krivichi?) groups that had migrated to these parts in the 11th century, bringing with them the time-hallowed traditions in their ornamental designs, which succeeding generations brought down almost to the present.

The ornamental designs we shall describe below possess the following salient features. They were commonplace in the North-Eastern districts of Vologda region and current right up to the 1930s. Further they were employed to embellish exclusively articles of a sacral significance, such as women’s blouses, notably the hems, shoulder yokes and sleeves, and also aprons, headdresses, sashes and towels. «The preservation in embroidery of the extremely early stages of human religious mentality… derives from the ritual character of the articles embroidered… the many that could be listed include the bridal kokoshnik diadems, shirts and blouses and mantles of wedding trains.

One special ritual item, long dissociated from its domestic twin, was the richly and intricately embroidered towel. Such towels were employed to offer the traditional bread- and-salt symbol of hospitality and welcome, to serve as the reins of wedding trains, or to carry a coffin and let it down into the grave. They were also used to adorn the «beautiful» corner in the house where the icons were hung, while the icons themselves, were deposited on towels specially made for the purpose», writes Rybakov about this «Tinen folklore». It is precisely such sacred ornamental designs that are to be seen in the Russian folk embroideries from the ethnographical museum in Vologda, which, quantity wise, will further serve as the comparative material used in attempts to elucidate parallels between the ornamental designs of North-Russian embroideries and those of the peoples inhabiting the vast expanses of the Eurasian steppes and forest-steppes at different times in history.

The lozenge and the rhombic meander represent one of the oldest ornamental motifs of the Eurasian tribes. It is to be found in paleolithic times, employed for example, to decorate sundry artifacts of bone, that were recovered from the upper paleolithic Mezin site near Chernigov in the Ukraine. In 1965, paleontologist V. Bibikova surmised that the spiral meander, the broken bands of meander and the rhombic meanders on items recovered from the Mezin site originated as an imitation of the natural design on the ivory of mammoth tusks. She conjectured there from that for upper paleolithic man this motif symbolized the mammoth which in turn embodied, as the basic target of the hunt, the concept of plenty and power (Fig. l).This motif comprised of rhombic meanders, spiral meanders and zigzags or flashes survived over the millennia (Figs. 2, 3, 26 and 27) modifying, but retaining their time-hallowed substance. We encounter this symbol of good fortune and prosperity and as a protective totem on both religious items and on pottery, in other words storages of food and water, again in later cultures, as for instance, the Balkan cultures (Figs. 2 and 6), the South-East European culture, the 5th millennium ВС. Tripolye-Cucuteni culture, etc. Rybakov notes: «The rhombic meander motif is encountered on vessels, especially the lavishly ornamented ritual vessels, on anthropomorphic figures of clay, also of an unquestionably ritual character, and on the clay thrones of goddesses or priestesses».

On Tripolye-Cucuteni pottery we encounter a stable repetition of the meander motif, which already differs to some extent from the upper paleolithic Mezin design, in that it is still more heavily geometrized and stylized (Fig. 7).

Apposite instances are afforded by the decor of the pottery recovered from the Frumushika I, Khebesheshti I, and Gura Veyi sites. All these meander motifs are, as a rule to be observed on pottery of the late Early Period and early Middle Period of the Tripolye-Cucuteni culture.

It should be noted that the swastika design may already be discerned in the bands of the double, right- and left-handed meander on bone artifacts from the Mezin site (Fig. 1). This is one more characteristic motif of Tripolye-Cucuteni decor, used either in its simplest version (Fig. 32) or with projecting lines from each bent arm of the cross (Fig. 52). Further the X-motif characteristic of Tripolye pottery decoration (Fig. 8) and likewise encountered to the north of Tripolye (Fig. 9), as well as the swirling triangle with its scroll head points are transmutations of the meander motif.

Summing up, we may outline a range of ornamental motifs, which though limited and unquestionably not exhausting the entire richness of Tripolye pottery decor, is still sufficient to characterize this culture, which we shall invoke further to draw comparisons with subsequent periods in history. They include the meander and its variants such as the spiral meander, the swastika (Figs. 46, 48, 50 and 51), more complex swastika designs, the 5-motif (Figs, 12 and 13) and the swirling triangle with its scroll head points (Figs. 44 and 49).

To establish the closest affinities, time wise, we shall naturally address ourselves to the pottery of cultures that, at different times existed within the present territory of the USSR on sites once occupied by the Tripolye culture.

Oddly enough such affinities in the pottery of cultures antedating the Timber-Frame (srubnaya) culture, and, for that matter, in the last named culture itself, are few and far between. The basic elements of the decor of Timber-Frame culture pottery, which according to B. Grakov dates to the 16th-12th centuries B.C. are chains of lozenges, rhombic lattices and rows of triangles on the shoulders of vessels, with bodies frequently carrying the characteristic slanted crosses, now and again composed of two intersecting 5-motifs.

Further stages in the evolution of the traditional ornamentation of pottery, incorporating an astounding plethora of sundry versions of the meander and swastika motifs, are to be encountered in the pottery of the Andronovo culture (also of the 17th-12th centuries BC. according to S. Kiselev) immediately contignous to the Timber-Frame culture. These two cultures concurrently existed over a lengthy period throughout the vast expanses of the steppes and forest steppes of the territory that is now the USSR. Kiselev indicated the affinity between the pottery decor of these two cultures observing that «… one cannot fail to note the obvious superiority of even early Andronovo pottery over the kindred Timber-Frame pottery». One cannot but concur. The extraordinary richness and diversity of meander and swastika motifs in Andronovo pottery decor are beautifully illustrated in the artifacts published in treatises concerned with the prehistory of Southern Siberia by Kiselev, in the monograph «The Bronze Age in Western Siberia» by M. Kosarev (Figs. 15 and 16) and also by V. Stokolos (Fig. 17) and F. Axslanova (Figs 18, 28 and 34) in their respective articles. Like the Timber-Frame culture the Andronovo culture with all its different versions ranged over a vast territory. Its western-most artifacts are to be found in the Timber-Frame culture area along the line between Donetsk and Voronezh. In the east the Andronovo culture extended along the southern Trans-Urals up to and including the Minusinsk depression. In the north it was bounded by the Southern Urals, while in the south it entered Northern Afghanistan. According to the evidence N. Chlenova cites in her article, Andronovo pottery in its Alakul version was common in Central Asia between the Amu-Darya and Syr-Darya, especially so along the banks of the Amu-Darya but also in the Kyzylkum desert.

She has indicated the impact of Andronovo pottery in its Fedorovo version, (the classical Andronovo version), and in its Alakul version on Amu-Darya Cherkaskul pottery. She also indicates that now and again Fedorovo type pottery can likewise be encountered in digs along the banks of the Amu-Darya. «Uniting the Amu-Darya region of Cherkaskul pottery with the North-Siberian, Urals and Volga region, we find that the Cherkaskul culture extends for 2,400 km from Kurgan-Tube to Kazan.» In the Amu-Darya region we find Cherkaskul pottery together with Alakul and Tazabagyab pottery; further Cherkaskul pottery is often encountered in the same sites together with Central Asian Khurmantau and Fedorovo pottery. "These stabilized combinations warrant our uniting the pottery of these three cultures into one group». Speaking of the purely Fedorovo pottery encountered west of the Urals, N. Chlenova says that it is known in forest and forest-steppe regions to the north but no further than the 56th parallel. One must necessarily add the vast expanses where the Andronovo tribes coexisted with the Timber-Frame tribes for so long a period, that ethnic and cultural contact between them was inevitable. This is well illustrated by the chart that Chlenova has appended to her article. The most intensive area of contacts was the Volga basin. Thus Timber-Frame and Cherkaskul pottery has been recovered from the same sites in Bashkiria, Timber-Frame and Fedorovo pottery has been found on identical sites near the Volga city of Kuibyshev, while a vessel of the transitional Timber-Frame Fedorovo version has been recovered from digs near the Volga city of Volgograd. Noting the extent of Bronze Age cultures, Chlenova indicates that a distance of between 1,200 and 2,500 km and more was not «the exception but rather the rule, reflecting the considerable mobility with the Kurmantau culture stretching for 750 km, the Cherkaskul culture for between 1,200 and 2,400 km, the Abashevo culture, for 1,350—2,300 km, the Alakul culture, for 1,300—2,150 km, the Fedorovo culture, for 2,500—2,700 km, and the Timber-Frame culture, for 2,700—3,000 km.»

B. Grakov says: «For some now unfathomable reasons of an inner order, during their first periods of between the 16th and 12th centuries B.C. the Timber-Frame tribes demonstrated constant migratory tendencies».

During the same period Andronovo tribes display similar tendencies and, evidently towards the middle of the second millennium BC. began to move intensively eastwards. Kiselev places the Andronovo culture between the 17th and 12th centuries BC. Kosarev says that: «In the transition period from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age Andronovo traditions of ornamental design localized for the most part in regions contiguous to the Southern and Central Urals.» He has dated the formation of the Andronovo type Cherkaskul, Suzgun, and Yelovo cultures as existing on the southern fringe of the West Siberian taiga and in the northern part of the forest steppes within the last quarter of the second millennium BC. He concludes that «the regions of the localization of the listed ornamental (cultural) traditions should evidently be associated with definite ethnocultural areas».

The Andronovo tribes were both farmers and stock-raisers, as repeatedly stressed by all the students of their culture. Thus, M. Gryaznov noted the prevalence of beef and dairy cattle in Andronovo herds. Describing what must have induced Andronovo tribes to migrate eastwards in the second half of the 2nd millennium BC. Kosarev notes: «Evidently the Bronze Age migration boom, more specifically the far-ranging Andronovo treks to the Altai, the northern regions of the Ob basin, the Khakassian Minusinsks depression and the northern regions of the land between the Ob and the Irtysh Rivers were largely due to the frequent droughts of the xerothermic period which many scientists believe incident to the Andronovo epoch.» During that period, due to growing dryness accompanied by the drying up and disappearance of many lakes and rivers, the periodical forest fire hazard increased greatly, which must have changed the scenery of the southern fringe of the West Siberian taiga, engendering large expanses of steppes and forest-steppes. «The frequent forest fires resulted in firesites continuing throughout the initial period of reforestation, which is during the forest-steppe stage».

The extensive pastures, plentiful, fertile flood lands and conducive climate may have all caused the growing Andronovo population to migrate bringing along the traditional ornamental motifs of decor and the traditional rituals, as cherished memories of their ancestral homeland.

The classical Fedorovo version of richly ornamented Andronovo pottery has been recovered primarily from barrows. Kosarev hence conjectures: " The highly

decorative pottery of the classical Andronovo style with its profuse geometrical

ornamentation was of a ritual nature which is why it was particularly characteristic of barrows and altars“. This points to a ritual sacred significance of the lushly ornamented pottery, with decor so reminiscent of the ornamental motifs in the late Early period and early Middle period of the Tripolye-Cucuteni culture. On the classical Andronovo (Fedorovo) — pottery the characteristically Tripolyan meander spiral and swastika, acquire greater diversity, through preserving the old archetype. Moreover, we know that precisely proceeding from these ornamental motifs experts identify all the different types of Andronovo cultures. Describing the specific character of the ornamental decoration of the pottery in question, Kiselev says „that it is most singular, and that the provenance of the different motifs is zonal and that the

place of a motif in each zone is usually the same.» He also says that the intricately formed Andronovo ornamental patterns «in all likelihood were seen as conventionalized symbols. and their specific meaning, their symbolical significance is stressed by their specific complexity».

M. Khlobystina is still more specific «Evidently, there existed a kind of communal nucleus, a community bound by norms of patriarchal law, which in turn possessed definite graphic symbols for clan affiliation, which the historian regards as encoded in the intricate interweave of the geometrical motifs of carpet-design pottery decor. It may be presumed that the dominant element of such ornamental motives is a range of figures disposed on the vessel’s shoulders.

Evidently, a study of their number and their combination, of Z-signs meanders, broken lines and their variations- may be definitive for elucidating the structure of each community.»

We share Khlobystina’s view of the sacrosanct tradition and the meaningful content of Andronovo decor, for it was not fortuitous for such decorated vessels to be deposited in graves, where they most likely discharged the function of a clan or tribal totem, serving as a kind of identify card on the dead person’s journey to his ancestors who by this token were to recognize him as a member of their clan or tribe. In this respect the ornamental pattern on Andronovo pottery likewise acted as a talisman on the journey into the hereafter.

Hence, we may once again state-a point that must be specially noted-that the carpel-design decor on Andronovo pottery was most likely a totem, a symbol of clan and ethnic affiliation for the person whose possessions were thus decorated.

This evidently continues throughout the Karasuk period between the 17th and

12th centuries BC, when the Scyth-Siberian Animal Style developed and during the Tagar period between the 7th and 1st centuries BC when often encountered on the celebrated open-worked Minusinsk belt plaques, in addition to representations of animals, is an orgamental design characteristic of Andronovo pottery decor, more specifically a lattice of 5-symbols (Fig. 11). These clasps or buckles, common throughout the middle reaches of the Yenisei River during the 3rd-1st centuries BC are to be met with the Ordos and Inner Mongolia-apparently due to the migrations starting at the turn of the Bronze and the beginning of the Iron Age of the tribes populating the southern fringe of the West Siberian taiga to the more southern regions. Responsible was apparently the wetter climate witch drastically expanded swamps and caused the taiga to encroach upon forest-steppes and steppe-lands territories. Nonetheless, yet in the Tashtyk period, extending from the 1st century BC to the 5th century AD, the tribes populating the Minusinsk depression were distinctly Europoid, which is borne out by the terracotta portrait mask recovered from some family burial vaults. Kiselev quotes a Chinese chronicler who noted that the «Kyrgiz», who inhabited what is today Khakassia, had «red hair, rosy cheeks and blue eyes». He adds that the 8th-century scribe Ibn Mukaffa had written of the Kyrgiz that they had «red hair and white skins». The same is reported by a Tibetan source noting that the K’inc’a (the Kyrgiz) had blue eyes, red hair and a disgusting, i.e., unlike the Tibetan, Mongoloid) appearance. Further, among the items Kiselev recovered from the ruins of an edifice near Abakan are some fascinating bronze door handles of local workmanship, that represent the fantastic countenances of horned genii which «forcefully emphasize the non-Chinese features. At any rate they are even more Europoid than the most Europoid of contemporary Tashtyk funerary masks.»

He adds: «The mask handles convey distinctly Europoid features particularly emphasized by the high bridged nose. We see a Europoid’s large features, of the type prevalent in Southern Siberia from oldest antiquity and virtually up to the start of the Christian era.»

We may thus state that the traditional ornamental pattern of meander, swastikas, and 5-symbols characteristic of Andronovo pottery decor continued to persist throughout Western Siberia and more specifically the Minusinsk depression up to the start of the first millennium AD, with some motives reaching Ordos and Inner Mongolia.

It should be further noted that time wise the closest affinities with Andronovo decor are to be found in North Caucasian sites of the turn of the second and first millennia BC, which period almost dovetails with that of the colonization by Andronovo tribes in the 13th century BC of Southern Siberia’s steppes and forest-steppes. Apposite instances are afforded by the artifacts that V. Markovin recovered from a burial vault by the village of Enghikal in Ingushetia that date back to the middle of the second millennium BC. They include plaques and fibulae with disk-shaped finials, embellished with die-stamped swastikas and meanders (Fig, 57). He adds that «regrettably North Caucasian Bronze Age pottery has been but little studied and hardly any comparisons have been drawn between it and the pottery of the steppe cultures»; yet, «… there is no doubt that precisely the steppe tribes from the lower Don area infiltrated the Kuban basin».

Among the artifacts R. Munchayev recovered from the Lugovoi cemetery in the Assinsk gorge in Checheno-Ingushetia, there are a high proportion of bronze plaques in the form of a double oval with die-stamped swastikas in the middle of each (Fig. 40). He adds that «… these items were always found near the skull or chest which allows to regard them as temple or pectoral plaques,» in other words, as protective totems. Note that both in the Nesterovo and Lugovoi cemeteries in the Assinsk gorge, mounds were now and again raised over burials.

Munchayev believes that there were cases when the ancient tribes here also erected barrows. All this is most reminiscent of Andronovo tradition-also indicated by the obligatory presence in burials of vessels and adornments, embellished with ornamental motives that are more than traditional of Andronovo artifacts.

In all likelihood analogous functions were discharged by the sheet bronze diadems embellished with an ornamental pattern identical with the decor of the double oval Lugovoi plaques, which B. Tekhov recovered from the TH graves in Northern Ossctia (Figs. 38 and 39). These diadems are decorated with circle», triangles and also a rule with meander and swastika typo motives. Tekhov says that similar diadems were recovered from a Styrfaz chamber-tomb in the Northern Caucasus, from the Armenian village of Geharot and from sites in Azerbaijan and Iran.

He has also indicated the characteristic meander and swastika motives on the Koban-type axes recovered from the same Tliburials.

Swastika-type motives complicated by many protruding lines are also to be observed in the decor of finds unearthed in a number of places in Azerbaijan as for instance, on a clay die and also on the walls of a temple and in the plaster work of an earth dwelling from the ancient village of Sary-Tepe, on the wall by a hearth (Fig. 29) and the pintaderas (Figs. 54—56) of the village of Babadervish, which date back to the 12th-8th centuries BC.

Consequently, the archaeological finds made in the Northern Caucasus and partly in the Trans-Caucasus, in Armenia and Azerbaijan, provide us with specimens of the use of ancient sacred ornamental motives that are characteristic of Mezin site artefacts decor and of Tripolye-Cucuteni, Timber-Frame and, especially, Andronovo pottery. Moreover, in the Caucasus these motives most likely have the same sacred functions of talisman and possibly of tribal and clan totem as were characteristic of Andronovo and, likely, Tripolye cultures.

We encounter echoes of swastika motives in Scythian jewelry, more specifically in the decor of horse trappings recovered from the Northern Pontine area. A. Meliukova believes that the openwork swastika plaques, also to be encountered in Thracian hoards are of Scythian origin, and adds that they appeared in the Northern Pontine area in the late 6th century BC. True, in Scythian art, all these forms have been markedly modified and transmuted (Fig. 47) to meet requirements of the conventionalized realistic trend known as the Scytho-Siberian Animal Style.