Бесплатный фрагмент - Zinka

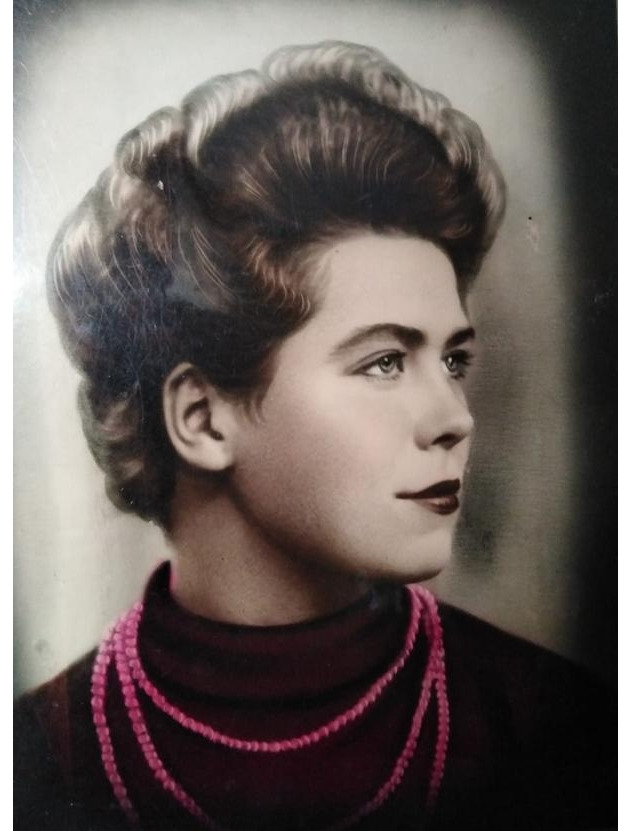

Devoted to my mother Zinaida

Part 1

What Was It Like

Chapter 1. The Bell Tower

The July heat made it difficult to breathe deeply. It was so hot that the water scoop, which had been hanging on a rusty barrel in the corner of the garden since Adam was a boy, burned the hands of anyone who passed by and scooped up the pitiful remains of rainwater that had run off the roof since the last rain at the end of June. You scooped up some water, splashed it on your face, and it seemed easier to breathe.

Vera had a lot to do that day. When did she ever not? From morning till night, she was busy as a bee, either around the house or in the garden. The garden was large and well-tended. It was time to hill the potatoes again, but you couldn’t get Grisha to do it. From morning till night, he was at the village council. Look at that! He was appointed the chairman of the collective farm. Oh well… There would be plenty of cucumbers, but in winter they’d all be swept away by the potatoes. She sighed heavily, looked up at the sky, and adjusted her kerchief, which had slipped down onto her forehead. If only there were a cloud…

The sky was high, the air was thick, like hot soup from the oven. It was time for Zinka to wake up; she had been sleeping for two hours after lunch. The village was quiet; the children had run around in the heat and dust. They were fast asleep after a plate of soup made from last year’s sauerkraut. They also drank a mug of milk with a crust of yesterday’s bread. They were full, and that was fine. Let them sleep. While they slept, Verka would do some chores and prepare something for dinner. She had to water the greens, but it was still too hot, so she couldn’t. In the evening, the neighbour’s boys would fetch water, and she would water the greens. Let them sleep… What could you do, there hadn’t been a war for a year then, thank God. They had to be patient, everything would work out, she was sure…

A pleasant coolness met Vera in the mudroom. Zinka’s old doll, which Vera had sewn from Grisha’s old trousers herself, fell at her feet. It was strange, Zinka always carried it with her. And she always slept with it in her arms. How strange it seemed. It was lying right in front of the doorstep in the mudroom. What was wrong with her? Maybe she was growing up? She was growing like grass. She would be three soon. How quickly time flew.

“Verka!!!! Verka!!!! Oh, my goodness!!!!! Oh, my God!!! Verka! Damn you! Where are you????

Vera’s heart sank. Zinka… She rushed into the house, pulled back the curtain — the boy was sleeping sweetly, sprawled on the floor on an old quilted blanket. Zinka was not in bed, as if she had vanished into thin air. Oh… She rushed to her neighbour’s piercing scream, her heart pounding loudly in her throat, her ears ringing.

Ninka rushed into the porch, kicked Zinka’s doll with her foot and, grabbing Vera by the sleeve, dragged her onto the porch.

“Oh, Verka, let’s run! She’s in the bell tower, the fool! She’s climbed up, but she’s afraid to climb down, she’s crying like a fool. And there’s no one to get her down — all the men are in the fields. What should we do?”

The old church gleamed white at the end of the village. It didn’t seem far away. But Vera’s legs wouldn’t carry her, she couldn’t run. Tears streamed down her face; her heart pounded in her throat. Lord, help me…

And a man was found. And Zinka was taken down. What a mess! She’d get it from her father…

Chapter 2. To School

“I’m not going! You go yourselves!” Zinka was crying in the evening, smearing tears across her dusty face. She had been running around all day with the village children and was soaked to her underwear.

“She’s not going! Who will go to school for you? Your father? Or maybe the shepherd Mikitka? Now get undressed quickly and run into the washtub, I’ll pour water over you, there’s still warm water left in the bucket.”

Vera pulled the dress off her daughter and pushed her towards the washtub. Her hair was wet, her head sweaty from running. Zinka resisted, pushing and getting stubborn.

“I’ll do it myself, leave me alone!”

Vera washed her daughter, who was already half asleep. She put her in a nightgown — her head barely fit through the neck. The girl was growing up; in the morning she would go to school.

The school was in another village, five kilometres away. Every morning, the children walked in a group along a short path through the field and the distant forest. In winter, the path was smooth and well-trodden, so they walked along it. In the morning, they walked one after another, half asleep. And after school, they laughed loudly, joked, imitated their teacher, and played snowballs. Or they just fooled around and rolled in the snow. The whole way to school took about forty minutes, but when the whole gang was fooling around, it took a good hour.

In the March thaw, children had to go around a ravine with meltwater for a whole mile. The water in the river also rose, flooding the old bridge, over which the children jumped from log to log, laughing and swearing.

Zinka did not like winter. It was dark in the morning, and the road through the woods was scary. The only thing that saved her was the children nearby. One would grab her, then another would lend a hand. And so, they walked. And the days were short. In the morning, it was dark when she left, and when she returned from school, it was dusk again.

The school in that village was small, with only one class. Their teacher, Zoya Vasilievna, met the children on the school porch wearing a shawl thrown over her shoulders and holding a broom in her hand. They used this broom to sweep the snow off their boots. The older children did it themselves, but Zoya Vasilievna always helped the little ones.

“Stop, don’t fidget! Look how much snow you’ve brought onto the porch!”

Zinka quickly and efficiently put her kirza boots under the teacher’s broom, sniffing. The girl was sent to first grade in kirza boots. Warm socks in winter. Grandmother Agafya knitted them. It was okay, the main thing was that they didn’t get wet, and that was fine… It was 1950. The country was rising from the ruins.

“Well, children! Who will tell us a fable, who is our hero?”

Zinka almost jumped out of her trousers, bouncing on the bench behind the crooked desk with her hand raised. She shook her hand and hissed like a kettle on the stove.

“Not ready again? Zinochka, come to the blackboard and tell us!”

Zinka rushed cheerfully to the blackboard with seven-league strides, tripping over her classmates’ bags and getting a couple of pokes in the back from them. And, before reaching the blackboard, she turned sharply towards the class, raised her hand in a theatrical gesture and shouted:

“Cock-a-doodle-doo!”

Zoya Vasilievna turned her head towards Zinka in amazement. The class burst out laughing.

All the way home, the children were running in front of Zinka, backing away and laughing, repeating in different voices:

“Cock-a-doodle-doo! Cock-a-doodle-doo!” And Zinka was so upset that they were laughing at her. Well, never mind! She would show them…

Chapter 3. The Older Brother

Grisha, Zina’s father, did not go to that war — they did not take him. He had been shot up in Finland war, and the military commissariat decided not to draft him, to leave him, so to speak, on the front line in the rear as the chairman of the collective farm — to command the women.

At the very beginning of the war, Vera and Grigory had a baby boy. He was chubby-cheeked, plump, and creamy. He had a good appetite. Nickolay, Kolka, son. Vera could barely cope, torn between the collective farm and home. Grisha was a poor helper, being the chairman. He had plenty of his own worries. He spent whole days at the village council, or he would go to the city to report to his superiors.

Food was very scarce in the 1940s. Everyone survived on their own farm. Grigory had a small apiary, inherited from his father. A cow, a piglet and a dozen chicken. They exchanged food in the village. You give me a couple of eggs for pancakes, and I’ll give you a jug of milk. They didn’t see any meat for months. Honey helped a lot. If it weren’t for the apiary, they would have been in real trouble. They survived thanks to honey.

Zinaida was born a couple of years after her brother Kolka, in 1943. A child of war. Her brother loved Zinka. That summer, when she climbed the bell tower, he was already five. Kolka hung out with older boys, running around the village all day long. Zinka often cried. She asked to go with Kolka.

“Take her, Nikolai, you can look after her at the same time. Mum needs to work in the field,” Vera asked her eldest son. Of course, he would look after her, who else would!

He would take his father’s sheepskin coat and turn it inside out. He would put it on, get down on all fours and growl, walking towards Zinka as if he were a bear in the forest. Zinka would burst into tears, squeal and smear snot across her cheeks. Vera would hit Kolka on the back with a towel so that he wouldn’t scare his sister to death!

Or Kolka liked to tease Zinka. He would get the boys to join in, and they would all shout together:

“They bought Rubber Zina in the shop! They brought Rubber Zina in a basket!”

“I’m not rubber!!!! They haven’t brought me in a basket!” Poor Zinka ran after them, crying her eyes out, smearing tears across her face. That was how brother Kolka and sister Zinka grew up. Sometimes hugging each other, sometimes in different corners of the house.

It was April, and the last snow remained as spring frost only in the ravine through which the children walked in their usual crowd to school. Kolka secretly took an old axe from his father’s barn and on the way to school stuck it into a birch tree on the edge of the village. He placed a jug under the wound to catch the birch sap. When they went back, the sap would have already started flowing. On the way home from school, Zinka remembered the birch tree and ran to it faster than anyone else. She ran up, threw herself against the trunk with her hands, and the axe fell out. The blade cut right through her leg. It cut her boot and left a deep wound. And there was blood, like from that piglet they had slaughtered the other day. The children were terrified. Oh, Kolka would get some from his father for taking the axe without permission, for not looking after his younger sister. He was always to blame in their eyes. Because he was the older brother. What could you do?

Chapter 4. A New Life

Grigory had been saying more and more often lately that life in the city was better, simpler.

“It’s time for us to go to the city, Vera. They’ve started giving passports to collective farm workers, so there’s no reason not to go.”

“Grisha, just leave everything behind? What about the house? The garden? The children are at school. And me? What will I do there, in your city? I’m used to the land, to the village.”

“We’ll move the house, log by log. I’ve already found a place and made an agreement with the men from the cooperative; they’ll do it for a reasonable price. We need to decide, Vera. It will be easier for us there. You’ll have your garden, and the school will be nearby. Is it good that the children have to walk five kilometres to school?”

Grisha had those conversations with his wife more and more often. And finally, he persuaded her. Oh, how frightening it was for Vera to start a new life. She wanted to consult with someone. But who could she ask for advice? The village women at the well would immediately wave their hands, get alarmed, and start trying to dissuade Vera. What did they know about a new, city life? Had they ever tried it? Grisha had. Sometimes he would stay late at the office with his bosses and spend the night at their place. There was running water and a warm toilet. He envied how city people lived.

Grigory forbade Vera to share her doubts and seek advice from anybody. He forbade it completely. Not a word! And who would like it if the chairman of the collective farm ran away from his post? But he had decided everything long ago and discussed it. They found him a job in the city and helped him move. The world is not without good people. Besides, Grigory knew how to form bridges and think everything through in advance. Life had taught him wisdom.

They packed their things quietly, on the sly. It was 1953, and winter was coming to an end. The cold and snowstorms were receding, giving way more and more to the sunny days of late February and the drizzle of early March. Kolka had no idea why the whole house was full of bundles and sacks. He came home from school, threw down his bag and ran outside to play with the village boys. He barely had time to eat. But Zinka was attentive and curious from childhood. She would ask a hundred questions and wouldn’t let up until she got a clear answer. A real pain in the neck! She turned ten. A wonderful and smart girl was growing up.

“Mum, why are you putting everything in bags? You took all our clothes out of the chests. Are you giving them away? Or why? Huh?”

“Your father and I are renovating, Zinochka. Renovating!” We’re going to whitewash the stove, and there’s a lot of painting to do. Everything will get dirty. That’s why I’m putting it away. Go on, Zinka, go and play. Don’t bother your mother! Don’t get underfoot!”

The day before the move, Zinka and Nikolai’s parents sent them to spend the night at Grandma Agafia’s. The men from the cooperative arrived and quietly dismantled their small house log by log in one night. They all pitched in, and the house was gone. Only the stove in the middle glowed white in the night. The moon was bright, providing light for their work. The village slept. Zinka and Nikolai slept on the stove at Grandmother Agafia’s house. A new life awaited them. A city life.

Chapter 5. At Grandma Agafia’s

An annoying fly prevented Vera from cleaning the pot with sand outdoors until it shone, as she liked to do. She waved the fly away with her wet hand, but the fly kept coming back, buzzing and buzzing. It kept trying to get into her eyes or crawl along her sweaty cheeks. The pest was persistent! Vera straightened up, groaning. Her back had been hurting for two months, ever since she moved. She rinsed the pot thoroughly from the barrel and hung it upside down on the fence. The pot was shiny and looked new. Sand was a good cleaning agent, a pleasant chore. A ray of sunlight reflected off the pot and into Vera’s eyes. Vera was pleased.

She looked back at the house. Wow, it was standing there as if they never left. Grigory had the men dig the foundation to the right size ahead of time. He chose a good place for the house. It was like a city, but not quite. It was on the very outskirts. There was a piece of land for a vegetable garden and a water tap nearby in the street. Wow! You turned the handle, and water flew into an old rusty bucket. It was time to buy a new bucket; it was already embarrassing.

Yes, Grisha was right. City dwellers lived comfortably, and easier. The school was a ten-minute walk away. It was big, bright, three stories high. And the teachers were so cultured, reserved, smiling at Zinka and her mother. Grisha was right, Vera was wrong to argue and doubt. She worried for nothing. Everything would work out little by little. There was no war, and that was fine…

Zinka liked her new life. The house was the same, familiar to her, the school was nearby. She didn’t have to get up at dawn and trudge through the ravine and the distant forest to get to class. The teacher was also good and kind. Zinka made friends, one of whom, Katya, came from the same village as Zinka. They lived in different streets there, but here, in the city, they lived right across from each other. So, they walked to and from school together.

When the friends got older, in fifth grade, after school they sometimes walked together to the village, seven kilometres away, across a distant field and a small forest.

“Katya, shall we go to Grandma Agafia’s after school today? It’s Friday, she’s cooking sour cabbage soup and has put the dough on.”

“Let’s go! My parents have gone to Moscow today to buy sunflower oil and sugar. They’ll be back late. I’ll have lunch there,” Katya was glad that she wouldn’t have to stay alone at home that day, bored and waiting for her parents to return from Moscow.

Grandma Agafia’s cabbage soup was special. No one else could cook sour cabbage soup so deliciously. It simmered on the stove for a long time on the cooling embers of birch wood. The embers sometimes shot up and landed in the cast-iron pot. And that made the soup even tastier and more filling.

So, the two girls would run through the forest to their grandmother’s village after school. They weren’t afraid of anything. And their parents didn’t scold them; they used to it. And Grandma Agafia was happy too — she was delighted with her granddaughter.

“Hey! Make some pancakes with holes in them, okay? Sour ones! And with sour cream!”

“What do you mean, with holes? On a leaven? Do you like your grandmother’s pancakes? Your mother won’t make you any like that.”

“Why wouldn’t she make them? She bakes delicious pancakes. But for some reason, everything you make is the most delicious, Granny, both the cabbage soup and the pancakes. And I’m always hungry by the time I get to you.”

In the summer, Vera would send Zinka to stay with her grandmother Agafia. Nikolai also spent the summer vacation with his sister at his grandmother’s, but reluctantly. He was already a teenager. They had fun at their grandmother’s in the summer. They walked from dawn to dusk and were hooligans. Zinka loved especially running barefoot through puddles after a summer thunderstorm, squealing with delight. The ground was warm and soft. There were no worries in her head.

“Oh, Zinka, what’s that moving in your hair?”

“Mummy, Kolka. What is it? Don’t scare me!” Zinka jumped and squealed, feeling something crawling and buzzing in her hair.

“Stop, don’t move, you fool! Wait, I’ll swat it!” Nikolai took a stick the size of a club, swung it and hit Zinka on the head. Of course, he hit the hornet, but at the same time, Zinka fell silent. On the grass. With her eyes rolled back.

“Oh my God, you killed her, you fool! Holy Mother of God! Zinka, Zinka!” Kolka’s friend yelled. “Hey, Zinka, get up, what’s wrong? I was just kidding… Zinka!” Frightened Kolka shook his sister’s shoulder.

Zina opened her eyes and, looking around, raised her hand to the place where it hurt badly. She felt a huge bump. And she quietly whimpered in pain.

“I’ll tell Dad everything, you idiot!” Zinka shouted and cried even harder. The boys around her breathed a sigh of relief. Zinka was alive!

In the village where the children used to go to school, there was a small club. Every weekend, they would bring a film to this club. Residents from neighbouring villages would flock to the cinema. Kolka and his friends also went to that club. Zinaida often asked to go with him.

“Kolya, are you going to the cinema today? Kolya, can I come too? I don’t want to sit with my grandmother all evening. It’s boring. All my friends are going, so take me too. Please take me!”

“You’re so annoying! Let your older brother go out! Why are you always following me around? Grow up already!” Kolka complained every time, but he took Zinka with him anyway.

“Kolya, do you want me to teach her quickly not to tag along with us?” Nikolai’s friend suggested it once.

“Yeah, you don’t know her very well! She has a temper! She takes after her father — everyone says so. She’s as stubborn as a bull!”

The club was on the edge of the village, and you had to walk past the cemetery to get there. They went there in the summer when it was still light, but they had to return when it was already dark. They walked in a large crowd, discussing the film, laughing, and eating the seeds left in their pockets after the film. And no one even thought to be afraid of the cemetery. But on that day, Nikolai’s friend ran a little ahead, threw an old sheet over his head, and jumped out at Zinka. The whole crowd screamed and scattered in different directions. The whole crowd. Everyone except Zinka. She stood rooted to the spot, clenched her fists, and froze.

“Yeah, you think I’m scared? Not a bit! You fool! You’re stupid — consider yourself crippled! I’ll tell my father — he’ll deal with you quickly! It was my Kolka who put you up to this. I heard you in the hallway. You don’t want me to go to the club with you. Big deal… I’ll ask some adults to take me with them; I don’t need you very much!” Zinka declared proudly, her voice trembling with indignation.

Chapter 6. The Goddess

Years passed, and life went on as usual for Vera and Grigory’s family. Zinka and Nikolai grew up, their parents worked tirelessly, raising their children and managing the household. They no longer moved the apiary from that village, leaving the beehives with their relatives. Vera’s vegetable garden was smaller and more modest, with four garden-beds and a small potato plantation, more for her own care than for winter supplies.

Zinka was a good student. She was especially good at maths. She enjoyed going to school, and she was always sociable, cheerful, but a little noisy. She loved justice very much. If Zinka saw someone hurting someone else, she would immediately intervene. Otherwise, she might even slap them. Zinka had a heavy hand.

The children would walk down the street after school. They would come home from school, throw their schoolbags in the far corner and go for a walk. In winter, they would go to the ravine, where the local men would build a hill for the children on the slope when the first frosts came. Zina and her friends spent all their time there. And in the warm season, they would play Cossacks and Robbers, Stand-Stop, Hali-Halo, and Bouncers. What games they played in their childhood! The children would run around with a ball until they were exhausted, then they would all go to Zinka’s bench by the gate. The bench was large and wide. It was comfortable, with a backrest, the centre of the universe. The children would gather around it and play quiet games to rest a little and catch their breath. Sometimes they played ring-around-the-rosy, sometimes they played tag, sometimes they played edible-inedible. And who knows what else. The days were long in summer, it got dark late, and there was no need to get up early in the morning. Why not play?

And so, several years flew by. Zinochka finished eighth grade and, together with her friends, went to a professional college for a large factory in the city. She studied during the day and met friends in the evenings, and they all went out for walks together. And among those friends and neighbours there was one boy, tall, blue-eyed, with a dimple on his chin. Very handsome. He kept glancing at our Zinochka. And why not? Zina had become such a beauty by the age of fifteen. She was tall, with long, thick hair and dimples on her cheeks. When she looked up, her eyes were like lakes… In a word, she was a goddess! Our Anatoly fell madly in love with Zinaida…

“Hello, goddess! Would you like to go for a walk today?” Anatoly decided to ask her out on a date. Her cheeks flushed, and sweat appeared on her forehead.

“Of course, I’ll go! Who else is coming?”

“Who else do you need?”

“Just the two of us? Why not all together? Katerina is already back from school, and many others are already at home.”

“Zin, do you really not understand, or are you pretending?” Anatoly plucked up his courage and blurted out. His heart was pounding like a bell in his chest, and his palms were wet. “I’ve loved you for a long time, but I was afraid to say so.”

Zinka listened, embarrassed, her head bowed, rolling a pebble back and forth in the sand with her shoe. “Let’s go!” she said, raising her head proudly and shaking her hair dashingly.

From that day on, it became a habit — Zinka would rush home from college after classes, and Tolya would meet her. In any weather, he would run to meet her with pleasure and joy.

“Hello, my sweetheart! My little snub-nosed girl! How long this day has been, how I’ve missed you! My goddess, my Zinochka!” They got along so well, always together, everywhere and always close by. One spring day, Zinaida’s school day ended, she rushed out of the college doors, hastily throwing on a light demi-season coat, and froze. Anatoly was standing in front of her, his face as white as snow and his eyes dull. He grabbed Zinka in his arms and began to sob…

“My God, what happened?” Zinka broke free from his embrace. “Has someone died?”

“I got my draft notice, Zinochka. My draft notice. I’m going into the army… It’s time, the time has come,” Anatoly said, gasping for breath.

In those years, boys served long terms of military service. Three years in the army, and four years in the navy. Zinaida’s heart broke, and her bag fell from her hands onto the dusty road.

“Tolya, my dear, what about me? Tolya, I can’t bear it for long. Tolya, I’ll die here without you, I swear to God I’ll die…”

Anatoly hugged his snub-nosed girlfriend and held her close. Zina buried her face in his chest, and he buried his nose in her hair, inhaling the familiar scent. They stood there for a long time. Zinka was crying quietly, whimpering, while Tolya was stroking his goddess’s back, whispering tender words and coaxing and reassuring her.

Chapter 7. Mailbox

A lot of neighbours saw the boys off to serve in the army on that warm spring evening. Anatoly’s friend Sergey, who was part of Nikolai’s group, Zina’s brother, was also joining the army. Kolka’s friends were a year or two older than him. Nikolai himself was studying to be a carpenter that year. He was handy and had known how to wield an axe since childhood. The very same axe that had struck little Zina in the leg during the spring birch sap season in the village.

The stronger boys went around the yards, pulling out tables, benches and stools. They covered the tables with clean linen tablecloths. They set out plates of all kinds, glasses, and shot glasses — wherever they had. The parents of the recruits had cooked meat jelly in advance, baked pies, and dug up sauerkraut and salted cucumbers from the cellar. Potatoes and meat jelly. What else could you want? They found an accordion player who lived across the street. They got hold of some samogon and sat down with their neighbours to see off their boys.

Zina came to the table with her parents. She was gloomier than a cloud. They sat her and Anatoly next to each other, shoulder to shoulder. Someone from the locals joked loudly that if they were bride and groom, they should be seated at the head of the table. They would have a wedding. Zina flushed and became embarrassed.

All evening, they were sitting at tables, gossiping and singing songs at one end of the table, then at the other. As soon as one song ended, they immediately started another, then a third. The young people with guitars gathered in a group on a bench near Zinka’s gate, singing their own songs and telling jokes on any topic. The boys were smoking quietly, glancing at their parents at the tables, while the girls were winking and whispering to each other. It was getting dark outside, and soon it would be time to go home. Locals shook hands with the new recruits and hugged them tightly, patting them on the back and offering words of encouragement as best they could.

And then there were letters. Zinaida continued her studies at the college. She was preparing to join the ranks of workers at the local factory. Her future profession was proudly called “semiconductor device tester”. Her brother Nikolai teased his sister.

“Zin, what are you going to be? A tester! Oh, I can’t!”

“You’re a fool, brother! You’re a tester yourself.”

“Does Tolya write to you? He probably doesn’t have time for you right now, running around the parade ground from morning till night. Forward march, march, march! Run around the wall with your forehead… Stand down!” Nikolai teased his sister every now and then, but she just snorted at her brother and sighed quietly.

The post box became the centre of Zinochka’s universe. It hung on the right side of the gate, blue, old, rusted in places. There were two rows of holes at the bottom of the box so you could see if there was anything there or if they were still writing. A woman named Shura was the local postwoman in those days. Her husband, Stepan, did not return from the war in 1945. She raised three children on her own, working as a postwoman, and in the evenings she went to wash floors at the school nearby. Aunt Shura usually walked down Zinka’s street before lunch, so by the time Zinaida returned from college, there was already something to be found in the old post box.

Every day after college, Zinka would walk and wonder whether there would be a letter from Anatoly or not. Would there be or wouldn’t there? She guessed by the railings and posts, by the puddles and sparrows, by the passers-by and local dogs and cats. She walked and talked to herself.

“If I meet two dogs and three cats on the way, it means there’s a letter!

If I see five children on the way, he’s written!

His letter will come; it won’t come. It will come; it won’t come. It won’t come… Or maybe it will. It’s all nonsense, all my fortune-telling. Of course there will be a letter today! And tomorrow, and the day after!”

Such conversations calmed her a bit and gave her hope for the best. And when Zinka turned to the corner onto her street, she saw her mailbox from far out of the corner of her eye. And through the holes in the post box, she could easily see the cherished envelope. The family did not subscribe to newspapers at that time; her father brought newspapers from work. What else could be in the box but an envelope? Of course, it was a letter! She quickly took out the key to the box, which she always had with her. Her hands were shaking, her heart was pounding, and she couldn’t get the key into the lock. Come on! Open up! There it was. A heavy envelope with familiar handwriting. Hurray…

Sometimes the postwoman Shura would walk by and meet Vera, Zinaida’s mother.

“Hello, Vera! Here you go, he writes and writes! Oh, he’s a good guy! And he has a good family,” Shura would sigh and, tossing the heavy postman’s bag higher on her shoulder, would hobble on.

“Yes, thank you, Shura!” Vera shouted after Shura. “How are you? Everything okay? Well, that’s good!” Vera said to herself, looking at Anatoly’s quick handwriting on the envelope.

Zina peered into the holes of the mailbox from afar it was white, wasn’t it white — and if the mailbox responded with darkness, her mood immediately soured, but there remained a glimmer of hope that Shura was walking towards her mother Vera. What if the letter had already been at home? She would dance and sing! Her mother always made her dance. And if her brother was at home at that time, it would be a whole concert, a lot of fun. Zina would dance and sing to them in joy. Kolka would put a stool in the middle of the kitchen and shout:

“Introducing the People’s Artiste of the Soviet Union Zinaida!”

She had to climb onto a stool and shout. What wouldn’t you do for joy? Just so they would give her the letter. They laughed until they cried, until they dropped. And when the envelope fell into her hands, she wanted to hide away immediately, to be alone, to read it in silence, repeating and rereading every word. And then again and again from the beginning. And the next day Zinka would walk home from college again, along the familiar paths, wondering whether he would write or not.

Chapter 8. The Sky Split in Two

Two winters and two springs later, as sung in an old Soviet song, Zinaida graduated from college and, together with her friends, joined the ranks of the working class in one of the workshops of a strong and advanced factory.

By the age of seventeen, Zinka had blossomed even more, stretching out and straightening her shoulders. Her hair was thick and shiny, she was tall and slender, with dimples on her cheeks. In a word, she was a goddess! The new girls quickly, easily and happily joined the factory team. At first, the work was simple — selecting, sorting, checking — and the newcomers coped with those duties easily, without any complaints from the foreman. The pay was piecework — you got what you put in. So Zinochka, like everyone else in the brigade, tried to exceed the norm. You could earn more money and it was nice to be among the leaders. You would be praised and thanked.

The girls worked at the factory, like everyone else, in two shifts. One week in the morning, one week in the evening. The morning shifts were familiar and understandable. You got up at dawn and were home by evening. But the evening shifts really threw even the young ones off balance. They started after four in the afternoon, and the workers left the workshops after one in the morning. Our Zina, of course, didn’t go home alone at night. They would get together as a group from different workshops, wait for each other at the factory, and walk through the whole town in a crowd. Zina and her friends lived furthest away, on the very outskirts. They walked briskly at night, not dawdling. They hurried to get home as quickly as possible and slip under a warm blanket to rest. In the morning, they could stay in bed a bit longer and get up much later.

The team at the factory was friendly, dashing and spirited. Hand labour did not prevent them from having fun, laughing and discussing things. They shared news, discussed their bosses, gossiped and talked about various topics. Zina was cheerful and lively in the team, often laughing heartily and, as foreman Nikolai Ivanovich liked to say, always smiling. And why be sad? Anatoly’s third and final year of service had begun. Letters came rather often, sometimes every day. Tolya spoiled his goddess with attention and loved her very much. The letters were always tender, heartfelt, and long. There was always something to write about, even if there was nothing to write about.

Zinochka’s school friend Katerina studied with her. The same Katerina who, after school, often liked to run away with Zinka to Grandma Agafia’s house through the woods and across the field to a distant village. So, Zinka and Katya grew up together. Sometimes, after school, Katya would go straight to Zina’s house while her parents were away, or vice versa, Zina would stay at her friend’s house until evening, until her mother called her home. They also saw the boys off to the army together. Katya had been in love with Anatoly’s friend Sergrey. The boys had been together since they were age mate, and they went to the army together.

Sergey wrote letters to Katya quite often. She beamed like a polished samovar when she received news from the soldier. With each envelope, she ran to Zinka to show off, waving the letter like a battle flag and dancing as she ran. Katya began to work with Zinka in the same workshop but turned out to be on a different shift and she rarely saw her friend Zinka. They only met on their days off and shared news about letters and work. In short, about life.

The summer of the boys’ third army year passed unnoticed amid their worries. Autumn arrived. In just a couple of days, the old maple tree near Zina’s favourite bench turned red and then shed its leaves. The sky was increasingly covered with heavy low clouds, and the autumn rains began. Katerina was in a bad mood all summer, Sergey’s letters were getting shorter and shorter, and they came less and less often. And in August, Sergey stopped writing to her altogether.

Zina was so happy after every envelope. And now it was awkward not to share her joy with Katya. She felt sorry for her friend, who was not herself. And there was nothing she could do to calm her down.

“Katya, dear, please don’t worry. I’m sure it’s just a problem with the post. Anatoly is serving in Germany, where the postal service is probably more reliable. Wait a little, you’ll see, everything will work out. And you ask his parents what’s going on.”

“Are you crazy? I’m afraid. What will they think?”

“Do you want me to ask? I’ll ask if he writes to them. I’ll ask how he’s doing. Do you want me to?”

Zinaida found out by chance from Sergey’s neighbours that Sergey was doing well and would be coming home in the spring with his young wife. She heard it while standing in line for bread. What news! Her ears rang. Her palms sweated. Oh, how sorry she felt for Katya… How would she tell her? She couldn’t! Let her find out, but not from her. Zinka couldn’t bring herself to tell her friend. What a bastard!

In less than two days, rumours of Sergey’s marriage in the army spread throughout the neighbourhood. Katya hurried home from work, walking sideways, her head down and her shoulders hunched.

“My God, what a shame, Katya! You’re embarrassing yourself in front of everyone! And don’t cry! Don’t even think about it! He’s not worth your tears!” Katerina’s mother lamented, clattering with dishes in the kitchen and throwing wood into the stove as the first frost set in.

“Stop wailing, Mum! It’s so sickening! Leave me alone, all of you! Zinka is trying to calm me down, and you’re still here! Enough already! What do you understand? What do you feel? Do you feel the way I feel? Do you know how I feel? He betrayed me, Mum! He betrayed me! I had the sky above my head, high above. And now it’s split in two! I have been waiting for him, I loved him, and I still love him!” Katya cried out loud. And her mother just beat her hands against her sides in despair and wild maternal pity for her daughter Katya.

Chapter 9. Waiting and Catching up

After the shocking news of Sergei’s marriage in the army, Zina was overcome with a sense of unease. Letters from Anatoly continued to arrive regularly, as heartfelt as ever and without delay. Shura, the postwoman, often stopped by the gate to chat, complain about her difficult life, and to deliver another heavy envelope to Zinaida or her mother. She would give the letter to whoever came out onto the porch when she called them.

September flew by with its short Indian summer, constantly showering the bench by the gate with gold and crimson maple leaves. More and more often, the morning began with a long, cold autumn rain. Zinka was sitting at the kitchen table facing the window, stirring the bottom of her plate of cold porridge with a spoon and staring at a single point. Raindrops dripped drearily and reluctantly down the window glass, drawing bizarre, curved lines. A crazy autumn fly was buzzing and ringing somewhere under the ceiling. There was no letter again that day. Nor yesterday. Nor the day before yesterday. Nor the day before that. No letters for two weeks. And anxiety made it impossible to breathe, to do anything, to think about anything. It made it impossible to live. And that fly… “Are you waiting? He has forgotten your name. Bzzz… He’s got married!!! Bzzzzz…”

Zinka grabbed a kitchen towel and, pushing a heavy chair away from the table with a crash, jumped up and angrily hit the wall with the towel, from where the endless buzzing of a vicious autumn fly could be heard. Noticing a shadow in the street out of the corner of her eye, she rushed to the porch in the hope that it was Shura, the postwoman. No, it wasn’t her. Kolka, her brother, had returned from staying in the village with their grandmother Agafia. Zinka darted back to the table and sat down as if nothing had happened. She grabbed a spoonful of porridge.

“Hi, sis! Still suffering? No letter today? That’s too bad…” Kolka sighed sympathetically, scooping a large mug of water from the bucket and drinking it in one gulp. He wiped his mouth with the sleeve of his old autumn coat and approached Zinka. She sat motionless.

“Come on, don’t be so nervous. Two weeks isn’t that long. It’s the army, not dancing in the park. Who knows what’s going on there…” Zinka continued to sit silently, not responding to her older brother’s daily exhortations.

Autumn dragged on in anxiety and anguish. The days grew shorter, and cold winds blew. Their mother kept the stove burning constantly. Grigory got some cheaper firewood somewhere, and he and Kolka chopped it up. There was enough firewood for the whole winter. There were no more letters. Along with them, Zinka’s joy, desire to work, and her desire to socialize with people in the factory workshop disappeared. No one recognized Zinaida, who had previously been so cheerful, open and lively. Katerina shared the news with the girls in her factory team, and the rumour spread throughout the district. Everyone understood and kept quiet, not bothering Zinka or disturbing her.

Anatoly’s parents’ house was a little farther down the street, and Zinka, returning from work and glancing from afar at the cherished holes in the mailbox in the hope of seeing a white envelope there, noticed Anatoly’s mother out of the corner of her eye, walking towards Zinka. Oh, how awkward…

“Zina, hello! I haven’t seen you for ages. How are you? Are you working? I’m worried, I haven’t heard from Tolik in a long time. What’s he doing… Does he write to you? Six months until he’s discharged, I wish it would happen sooner. I miss him.”

“Good evening. No. He doesn’t write. I don’t know what to think anymore. Rumours are going around the street,” Zinka muttered and, lowering her head, hurried away, feeling her cheeks flush with shame and embarrassment.

Vera looked at her daughter, at her suffering, and her heart bled. She was ready to run to Shura, the postwoman, and bring back the cherished letter. Shura stopped coming to Zinka’s gate so as not to torment her soul unnecessarily. It’s true what people say, that waiting and catching up is the hardest thing for a human being.

Chapter 10. New Shoes

A ray of spring sunshine shone brightly into Zinka’s left eye. Reluctantly and grumbling, Zinka rolled over onto her other side and pulled the blanket deeper over her ear. The alarm clock ticked annoyingly on the bedside table, and at the end of the street, someone’s rooster crowed endlessly. Half asleep, Zinka realized that it was Saturday and there was no need to rush anywhere.

In April the last snow in shady places and ravines melted. Spring was long, with night frosts. The cold April was followed by a very warm May. Dawn came early, and the evenings became long, warm and pleasant. Along with the last snow, Zinka’s anxiety slowly and reluctantly faded away, giving way to strong resentment. How hurt she was… There was not a single letter. Zina tried to avoid chance encounters with Anatoly’s parents, giving their yard a wide berth. Mother Vera often muttered to herself, clattering pots and pans by the stove, that the Herod had disgraced the whole street, getting married, probably like Sergey. And her Zinka was waiting and suffering. What a stupid girl! There were so many good guys around. There was Slavka across the yard, and then there was Yegor Solovyov, and there were plenty more! She’d been locked up for three years, not going to dances or clubs. All the girls in the factory brigade went dancing to the park in the summer or hiking. Nowhere! Like some kind of nun. A recluse. In a word, a fool!

Zinka listened to her ageing mother’s mutterings and lamentations and gradually began to agree with her in her heart, feeling sorry for herself and nurturing her resentment. Her resentment grew alongside her bewilderment. Could that really happen? To stop loving someone in a single day? To stop talking about love and tenderness in letters. In a single moment.

Zinka lay there on that sunny Saturday morning, dozing and turning all these thoughts over in her head. The girls from the brigade were going to the city park to dance that evening. They invited her to come along. Maybe she should go? That was what her mother said. And Katerina no longer pined for Sergei.

“Go on, Katya will be smarter than me,” Zinka thought and calculated every time. Her father had recently travelled to Moscow for a regional meeting of collective farm chairmen, and he managed to get his daughter a pair of Yugoslavian shoes with pointed toes, the most fashionable ones. They were a dream, not just shoes. Few of the girls at the factory had anything like them; they were impossible to get. They were called “boats”. If it weren’t for Dad… They fit Zinka perfectly. She saw them and squealed with joy, kissed her father on the ear, and rushed to try on her new shoes, scattering her old worn-out slippers across the floor. Then she twirled around in front of the mirror, drawing waltz patterns with her very slender legs, while her mother and father smiled and exchanged glances, winking at each other. Well, thank God, she started smiling…

“Mum, I’m going dancing today!” Zinka declared resolutely, coming out of her room into the kitchen to her mother, who was baking fluffy pancakes on yeast dough, deftly placing the frying pan in the oven. Pancakes were baked on Saturdays or Sundays and served with sour cream and melted butter. Grandmother Agafia taught her mother Vera how to bake them. They were filling, inexpensive and very tasty.

“That’s right, Zinochka! That’s right!” exclaimed Vera, straightening up from the stove and turning to her daughter, holding her sore lower back. Zinka stood dishevelled after a night in a long cotton nightgown. Vera’s cousin sewed shirts, trousers for Grigory and Kolka, and shirts. He was a tailor in the city, and Vera often asked him to help her get dressed. By summer, they had sewn Zinochka a very elegant dress, fitted at the waist, with a fluffy skirt and a pretty neckline that revealed her beautiful long neck and collarbone. They chose white fabric with large black polka dots. And a wide black belt at the waist. Yugoslavian shoes went very well with that dress. It was so beautiful! All day long, Zinka was trying the dress and shoes on and twirled in front of the old dressing table, sometimes lifting her thick long hair up, sometimes letting it fall over her shoulders.

Chapter 11. Good!

The city park greeted Zinaida and her friends with a light evening breeze and Edita Piekha’s song “Good!”, which was all the rage that year. Several dozens of Zinaida’s peers were already dancing the trendy twist on the dance floor at the bottom of the park.

“A person walks and smiles, which means that person is well! Good!!” Edita was singing invitingly. The young people on the dance floor echoed her in unison, rhythmically and joyfully throwing their hands up in the air with each “Good!” and casting appreciative glances at those dancing nearby.

A wide alley lined with old lime trees and lampposts led to the dance floor, casting whimsical, curved shadows here and there on the alley and lawns. The trees and lanterns lined up in a row and seemed to bow to every young beauty who proudly and shyly descended the park alley to the dance floor to the sounds of music, expecting some kind of magic.

“Good! Really good!” smiled Zinochka, satisfied with her decision to have fun on that warm Saturday evening, and made her triumphant march down the alley, proudly raising her head, adorned with a tall, fashionable hairstyle called a Babette, like a crown. A white polka dot dress to the knees, a wasp waist playfully emphasized by a wide black belt, and white Yugoslavian pointed-toe shoes in the latest fashion favourably distinguished the Goddess from her friends, who were dressed more simply and were chattering beside her about their latest news, constantly interrupting each other. Her left heel hurt a little from her new shoes, but that seemed trivial compared to her heart beating loudly and strongly from unfamiliar impressions and feelings.

Overtaking the girls, a noisy group of guys with a guitar passed by, singing about the black cat who lived around the corner and whom everyone hated, poor thing.

“Hey! Look who it is! Little sister!” Zinaida heard the voice of Kolka, her brother.

“Kolya! Introduce me to your sister!” the guitarist exclaimed playfully, continuing to strum the strings and repeat the same chord several times, smiling and holding a cigarette under his moustache, so fashionable in those days; he was mesmerized by the image of Kolka’s sister.

“Move along, I didn’t raise her for you!” Kolka replied haughtily and arrogantly, and the company moved on, interrupting the singer Edita Piekha with their hit song about people not getting along with cats.

The old dance floor was flooded with spotlights and it glowed brightly in the dark summer park. The breeze had completely died down, and the evening coolness descended on the park. The rhythmic song ended, and during the musical pause, laughter, the chatter of girls and the voices of young men could be heard. The dancers stood in groups, chatting and relaxing after the working week.

Zinka and her friends entered the dance floor and chose a place to dance. They were flocking together, chatting cheerfully, shouting over each other and the music. “Great!” thought Zinka, moving nimbly to the beat of the latest hit song. Finally, the fast and energetic twist on the dance floor gave way to a melodious tune, hinting to all the dancers that it was time for gentlemen to ask ladies to dance.

The girls, hearing the first chords of the slow dance, dispersed, or rather scattered across the free benches, leaving the centre of the dance floor half empty. Each girl sat and showed with her whole demeanour that she was not going to dance that slow dance, and that she was definitely not waiting to be asked to dance under the eyes of all in the park.

Zinaida had barely taken a step to choose her cherished secluded spot on the bench when she heard a man’s voice behind her.

“Excuse me, for God’s sake, excuse me. Would you dance with me?”

Zinka turned around in confusion. In front of her there was a handsome brunette of medium height with amazing eyes; he was smiling shyly.

“Oh, I don’t know, I wasn’t planning on dancing slow dances. Well, just once, then,” Zinochka said hastily. The guy gallantly took her by the elbow and led her to a free spot in the centre of the dance floor. He took her hand in his, gently placed his other hand on her black belt at her waist from behind, and the couple began to move to the lovely sounds and approving exclamations of those around them. “All right!” Zinka suddenly thought, breathing a sigh of relief. “Well, okay, let it be…”

Chapter 12. No Big Deal

“I’ve seen him somewhere before,” thought Zinochka, dancing slowly with a stranger to the enchanting sounds of music. Her heart was pounding in her ears, and she could barely hear what her dance partner was saying as he leaned slightly towards her right ear. Zinaida nodded in response, smiled, and stole glances at her friends, who were watching from a bench directly opposite.

“I know you. Your house is across the street from ours. My aunt lives on your street. I’ve seen you there a couple of times. I wasn’t friends with your boys when I was at school. They’re all much younger than me, I have my own friends, who are older.”

“He’s quite grown up. I wonder how old he is. 28? 30? Why is he here? Men of that age are usually already married; some even have small children. He’s so handsome… He looks like an actor. Oh, that’s it! He’s the spitting image of Yuri Yakovlev! He even has the same hairstyle, with a slightly receding hairline. Oh, he’s so handsome”, thought Zinka, not forgetting to keep up the pleasant conversation. “He played the Idiot in Pyriev’s film. You know, the one based on Dostoevsky. I hope he’s not an idiot.”

And at that very moment, something terrible happened. Her dance partner Valentin clumsily stepped on the pointed toe of her left shoe with his entire boot. New, Yugoslavian, white, leather, never worn before! Zinaida was scalded with boiling water and electrocuted. “He’s an idiot!”

“Oh, my goodness! Forgive me! How clumsy of me,” Valentin continued to apologize desperately, escorting Zinka, stunned by the new acquaintance and the thought of her ruined shoe, to her friends. They giggled and whispered playfully on a bench in a dark corner of the dance floor, waiting for the lucky chosen one.

The drums beat energetically, and the cymbals rang out the first chords of another twist. The dance floor gradually filled with young people, and in a couple of minutes there was no room to swing a cat.

“Zinka, do you know him? Who is he? What’s his name? What did you talk about?” her friends asked, interrupting each other and glancing at Valentin, who was dancing the twist with his adult friends not far from them. Zinka continued to think confusedly about her shoe, not yet knowing whether to be upset or not. In the dark, it was impossible to see if the toe was damaged.

“He really messed it up with his shoe, probably scraped off all the polish. What an idiot! Well, even if he did, Dad will fix it with something. And where else would I wear these shoes except for dancing? It gets dark in the evening anyway. It’s a pity, of course, but it’s not a big deal!”

Zinochka resolutely dismissed her sad thoughts and picked up the rhythm of the twist. Her white dress with black polka dots burned like a bright spot, flatteringly emphasizing the slender silhouette of the snub-nosed goddess.

Chapter 13. Half an Hour

Zinaida returned from dancing that evening, not alone. Halfway there, Valentin, her new acquaintance, caught up and walked with them. After all, they were all going in the same direction. On the way, they were joking, laughing and singing to the disapproving clapping of the windows of the nearby houses at such a late hour. It was a very warm May evening, and the hooligan nightingales were already singing their roulades at full throttle, inviting female nightingales to their “mansions’ ready for family life.

Zinaida was a little nervous and kept glancing at Valentin, noting to herself that she liked the guy very much. He was courteous and polite. He didn’t laugh like a horse for no reason. He was also handsome. Probably smart. And, as it seemed to her, a little shy, even a bit embarrassed.

“My Tolik is just like that. Just like my Tolik,” Zinochka sighed. Remembering Anatoly, once so dear to her and now so far away, Zinka’s heart ached. But at that moment, the whole company laughed at a joke that Zinka had missed, lost in her thoughts.

Her friends gradually dispersed to their homes, through their gates. Valentin accompanied Zinochka to her house. Zinaida habitually glanced at the holes in the mailbox. The mailbox was empty again. The scent of blooming lilacs wafted from the gate, the sound of a guitar could be heard in the distance, and local teenagers were singing a familiar song out of tune. One window in Zinka’s house was lit, the kitchen window. “Mum is awake, waiting. She wants to know everything. I’ll tell her about him,” thought Zinaida. There was an awkward pause, broken by the melodious song of a local nightingale, inviting conversation.

“Shall we sit for half an hour? It’s such a warm evening,” suggested her companion, taking Zinaida by the hand and feeling embarrassed again. Zinka fearfully withdrew her hand from Valentin’s warm palm, and the couple sat down on a bench for half an hour, as agreed. And then another half hour, and dawn extinguished the bright kitchen window. Mother Vera breathed a sigh of relief when she heard muffled voices at the gate, recognizing her daughter’s voice and listening intently to the soft baritone of the stranger.

With the first cockcrow, Zinka realized that half an hour had flown by unnoticed and it was time to go home to her warm bed. Valentin gallantly escorted his new acquaintance through the gate and, looking back and waving his hand, smiling at his new thoughts, cheerfully walked across the street to his house, whistling Black Cat, whom everybody hated and with whom the whole house did not get along.

At home, Zinka tiptoed through the porch, clumsily knocking over an empty bucket. She caught it, hissing, swearing and giggling. She quietly opened the door to her room, which creaked treacherously in response. She clumsily pulled off her new dress, threw her Yugoslavian shoes with scuffed toes under the bed, away from her mother’s eyes and her own, so as not to get upset, and darted under the blanket. Sleep was nowhere to be found. Zinka lay there, her mind racing with all sorts of thoughts, remembering things from years past, fragments of that night coming to mind through her drowsiness. Through the blanket pulled over her ear, she could hear the morning sounds of the street. The roosters were already crowing loudly, someone’s goat was bleating, and gates were creaking. A loud stream of water hit an empty bucket on the tap near their house. A new day was beginning, and Zinaida fell asleep, lulled by its sounds and new hopes.

Chapter 14. Kitchen Symphony

Zinka was awakened by pots and pans clattering loudly in the kitchen in the hands of her mother Vera, who was burning with impatience and curiosity.

“She’s asleep! Can’t she think about her mother!” Her mother had been awake all night, waiting for her to come in, lie down, and turn off the light. It must have cost a fortune for one night! Vera grumbled and lamented under her breath, rejoicing in her heart that her daughter had finally made a right decision to have done with her solitary life. Vera was barely managing to wipe her hands on her apron, put pots and pans on and take them off the stove, with onions sizzling in sunflower oil for future cabbage soup with a piece of pork. Food was scarce in those years, but Grigory had acquaintances everywhere from his time as chairman of the collective farm. Sometimes they would send meat from the city meat cutting plant, sometimes they would offer fresh vegetables from the vegetable warehouse. And sometimes they would bring hot bread from their acquaintances at the local bakery as they passed by.

Zinka finally woke up from the kitchen symphony and, completely dissatisfied, rolled out into the kitchen in a crumpled calico nightgown. Her fashionable Babette hairstyle, so chic the day before and dashingly ruined by a huge feather pillow during the short night, stuck out to the side like a princess’s crown. Zinaida’s feet were adorned with old, worn-out slippers from the time since Adam was a boy.

“Can you keep it down? Mum! It’s not even eight o’clock, and you’re keeping me awake! You’re making enough noise for the whole of Ivanovo!” Zinka grumbled under her breath, shuffling her slippers towards the bucket of water.

“The suitors have already pissed on the gate; it’s time to get up! Couldn’t you have come earlier? You showed up with the roosters!”

“Mother! You’re so interesting! You’re impossible to please! First you complain that your daughter is a recluse, then you tell her not to come. Mother! I’m not fifteen years old, there are girls my age in our factory brigade who are already married, and you still control me. Enough already!” Zinka realized that she had gone too far and that her mother really wasn’t used to waiting for her until morning and getting nervous. She smiled conspiratorially, replacing her anger with kindness, and asked insinuatingly, approaching her offended mother.

“Who wants to know how her daughter went dancing for the first time in three years? Who should I tell something interesting to? Who here isn’t arguing or angry?” Zinochka hugged her mother and kissed her cheek loudly.

Vera happily wiped her hands dry on her apron and, pulling out an old, worn stool weighing a ton from under the table, sat down eagerly to listen to Zinka, spreading out an old apron with a huge sunflower painted on it on her knees. Zinka was singing like a nightingale, recounting yesterday evening in vivid detail, gesturing animatedly, omitting only one detail — the ruined shoe.

“Why did he invite you?”

“Whom else? Mum! Well, you know her! Listen, don’t interrupt. Anyway, his name is Valentin, he’s a welder, he’s already working. He looks about 28. He’s handsome, just like the actor Yuri Yakovlev from the film ‘The Idiot’. I hope he’s not an idiot.” Vera was listening and nodding approvingly. “Their house is across the street from ours, closer to the bus stop. He has a younger brother and a sister. He says he’s seen me and knows me. His aunt lives on our street.”

“Wait a minute”, Vera clapped her hands. “Valentin? Valka? Frosya’s son? That must be Marusya’s nephew. His aunt lives on our side of the street. So, I know him, Frosya’s son. Victor is his younger brother; Zina is the youngest. Good heavens, Valentin! Is he that grown up already? Well, well. How time flies… Handsome, you say? I haven’t seen him for ages. They’re all good-looking there. Froska is such a beauty, and her daughter is stunning. Slender, wavy hair, eyes, eyelashes. Look, Zinka too. She’s studying at your college now, just enrolled. I know their family, I know! Wow…”

After chatting for another half an hour, mother and Zinka happily went their separate ways, each to her own chores and concerns. Mother went to finish cooking the sour cabbage soup, and Zinaida, having received approval from the chief “prosecutor,” exhaled, satisfied, and shuffled off to her room in her slippers. She collapsed into bed with the thought that the interrogation was over and she could sleep for a couple more hours. The next day would be Monday, and she would be working the night shift for the entire following week

Chapter 15. The Conspirators

Flying out of the workshop at one o’clock in the morning, overtaking her friends and jumping over the steps like a madwoman, Zinka plunged from the factory porch into the cool May air of the night city. Immediately, her gaze darted into the darkness at the end of a small square away from the factory’s Honour Board. There, as usual, a cigarette was burning, sometimes flaring up, sometimes dying down again. From the first day they met, Valentin asked the Goddess for permission to meet her after her night shift and walk her home. Zinka, of course, liked the young man’s attention.

“Wow! He has to go to work in the morning, and yet he drags himself across the city at night. When does he sleep?” Zinka wondered a couple of times, feeling sorry for her suitor and at the same time appreciating his care. But in fairness, it should be noted that Zinka felt sorry for Valentin only a couple of times during that first week of nightly escorts. She had other things on her mind. They walked home slowly, laughing, and Valya gallantly held the Goddess by the elbow in places where the city’s streetlights poorly illuminated the uneven road. By the end of the first week of night walks, Zinka caught herself thinking that for the first time she had not glanced at the holes in the post box, which had been sad and waiting for news from the soldier for several months.

At work, Zinaida came back to life, cheering up to the great delight of the foreman and the girls from the brigade. She laughed loudly and heartily again, engaging in conversation about this and that, while her hands worked at great speed, checking and placing small semiconductor parts into the trays. In between jokes and conversations, Zinka kept thinking about her new friend.

“He has the same blue eyes and dimple on his chin as Tolik,” Zinka sighed sadly from time to time, remembering her soldier boyfriend less and less often. There was still no news from Germany, and Zinka and her mother were convinced that Anatoly’s parents were hiding their son’s marriage from their neighbours. Tolya was supposed to return at the end of May, but he never arrived.

“I bet some clever commander’s daughter in Germany has snatched him up,” Vera, Zinka’s mother, speculated when she met Zinka in the kitchen in the morning. Zinka just sighed as she listened to her mother and lazily stirred her spoon in a bowl of hot semolina porridge.

“So, he’s not coming, he’s in no hurry. There’s no point in waiting and feeling sorry for yourself. Look, there’s a handsome young man who has his eye on you. And he has a good family. I saw Fronka in the shop the other day, and she said it was definitely her son, Valentin. He’s told his mother about you, and she’s delighted. Let them be friends, she says, he’s a good guy, conscientious, hard-working. He earns well. He doesn’t drink alcohol. He only smokes. But who doesn’t smoke these days? Kolka from the fifth grade used to collect cigarette butts on the streets, the little shit. As long as he’s a good man, caring and loving,” Vera thought sadly of her husband Grigory. He was staying out later and later in the evenings, coming home and averting his gaze from his wife’s searching, questioning look. Vera was troubled by doubts, but she refrained from asking questions, afraid to hear the truth that would break her heart.

“As long as everything is fine with my daughter and Kolka,” Vera thought, continuing to bustle about the house and garden. “Zinka needs to get married, get married. And everything will work out.”

Eight weeks of a hot but very windy summer flew by unnoticed. At the end of July, Valentin met Zinochka at the factory gate after her night shift and, smiling triumphantly, announced that he had been visiting her mother Vera that evening and she had fed him pancakes with butter. And Vera had agreed to give Zinaida to him as his wife. Zinka stopped, raising her blue eyes in amazement at her friend.

“What? What pancakes? What agreement? Have you both gone mad? Is that normal? Conspirators! He went to visit…” Zinka lamented, but her heart was bursting with joyful excitement at the changes. Two months had passed since they met, and he was already asking her to marry him. What a go-getter! But Zinka liked his assertiveness and determination, there was no denying it. A real man!

Chapter 16. Too Late

The wedding was set for the second half of August, right on Apple Spas. Valentin sent matchmakers to the parents of his Pearl — that’s what he affectionately called her. She looked like a pearl in her white dress in the darkness of the city park when he saw her that evening. Grigory and Vera received the matchmakers with dignity, respect and reverence, as is customary in Russia. Vera and her daughter cleaned the house until it sparkled, prepared and set a beautiful table in the centre of the living room, and put on their best clothes. Grigory donned his only formal suit, which he wore as chairman of the collective farm to meetings with the authorities and to the capital for sunflower oil and buckwheat. The groom’s mother, Euphrosyne, Frosya, came to woo her son with her sons Valentin and Victor; her younger daughter, Zinochka, preferred to stay at home and did not go. They sat at the table, talked, and had lunch. The parents solemnly gave their consent to the joy of the young couple and accompanied the guests to the gate.

A month flew by in anxious anticipation, worries and bustle. They went to Moscow to the Eliseevsky grocery store to buy food for the wedding table. After her day shift, Zinochka kept popping in to see her uncle, a tailor, to try on her wedding dress, for which he had obtained lace fabric through his connections with other tailors. They found a veil among her friends. Short, fluffy, with a delicate wreath, it went perfectly with the wedding dress that was fashionable in the 60s — not long, knee-length, for the slender legs of a goddess. Bare shoulders, the same wide belt at the narrow waist and a fluffy sun-flared skirt. A sight to behold, not just an outfit!

August arrived, it began to get dark early, and the high starry sky hung like a black dome over the old bench by the gate. Valentin hugged Zinochka tightly and, wishing her good night, hurried home early, promising his mother Euphrosyne to help with some men’s chores around the house.

Valentin’s father, Alexei, was buried early, immediately after the war. Euphrosyne’s husband, like many soldiers, reached Berlin with honour, but tragedy struck in the early post-war years. Late one evening, a group of townspeople came to their street and got into an argument. One word led to another, one refused to back down, another argued, and a third pushed. Alexei stepped in to separate the young men, helping out the local boys. One of the city dwellers pulled out a knife. The wound proved fatal… Euphrosyne was widowed at a very young age, left with three children and torn between endless chores around the house and garden and hard work at the city bakery. She never remarried, as she was too busy raising her children on her own. Frosya had no one to rely on, but Valentin and Victor grew up, followed by her daughter Zina. All the children helped their mother from early childhood — her daughter with the housework, and the boys with hammering, nailing, repairing, digging the garden, and hilling the potatoes. Efrosinya always had a lot of work to do. Who doesn’t?

Zina closed the creaky gate behind herself, slamming the stubborn latch, and headed down the path to the porch. The kitchen window was lit, and the shadows of her tired parents flitted across it. They were surely eagerly awaiting their daughter’s return for the late dinner. Somewhere in the evening silence, a dog was barking loudly, followed by a second, and soon a friendly dog choir broke the quiet and leisurely pace of the dark August evening. Behind the gate, Zinka heard a painfully familiar voice.

“Zina, is that you?” Zinaida froze in her tracks. Blood rushed to her face as if someone had splashed boiling water on it. This couldn’t be happening. This couldn’t be happening! Closing her eyes, Zinka stood still for a few more seconds, listening to her heart pounding in her throat, and slowly turned to face the gate, gasping for air.

“Zinochka, my dear, tell me it’s not true! Open the gate! Please! It’s me! I’ve arrived half an hour ago, I’ve just arrived! What are they saying? Zinka! What are they all talking about? It’s not true! It’s all not true! Here I am! I arrived! I couldn’t! I couldn’t do anything! Something terrible happened, Zinochka! Open up! You’re here, I can see you, open up! I’ll tell you everything! I beg you, believe me! Something terrible happened there! We barely got out of there,” Anatoly repeated incoherently, tugging at the handle and breaking into shouts and whispers, realizing that he would alarm Zinka’s parents and they would rush out onto the porch.

Zinka threw open the gate, and Anatoly barely managed to dodge out of the way. She rushed towards the soldier, pounding him with her fists and not thinking straight. Tolya clasped his goddess in his arms, repeating the same thing over and over again.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.