Бесплатный фрагмент - Zen Master Rilke: There Are No Teachings

Some Notes on the Booklet

This little book is the third in my series on Buddha and Rilke. The book contains three thought-provoking etudes, which may seem rather bizarre to the reader. The point is that the poet appears in them as…

a Zen Master.

In the first etude, the poet talks to an unknown patriarch of the Chan school about how there is no doctrine to follow in order to gain an understanding of one’s original nature. In the second etude, the poet rejects The Buddha’s Discourses; he reflects on his own and only his own journey towards his authentic Self. In the third, the poet has a conversation with Gautama Buddha and his disciple about… the nightingale’s paradise and silence.

Each etude features Rilke’s authentic voice. All his words are quotations from his letters; they are given in my translation. The sayings of Gautama Buddha are taken from The Gospel of Buddha by Paul Carus (1852—1919) (The Gutenberg Library). The Patriarch’s remarks are my interpretation of some statements made by the great Chan teachers Hui Neng and Linji Yixuan.

To make the text easier to read, speech marks have been removed from all dialogues.

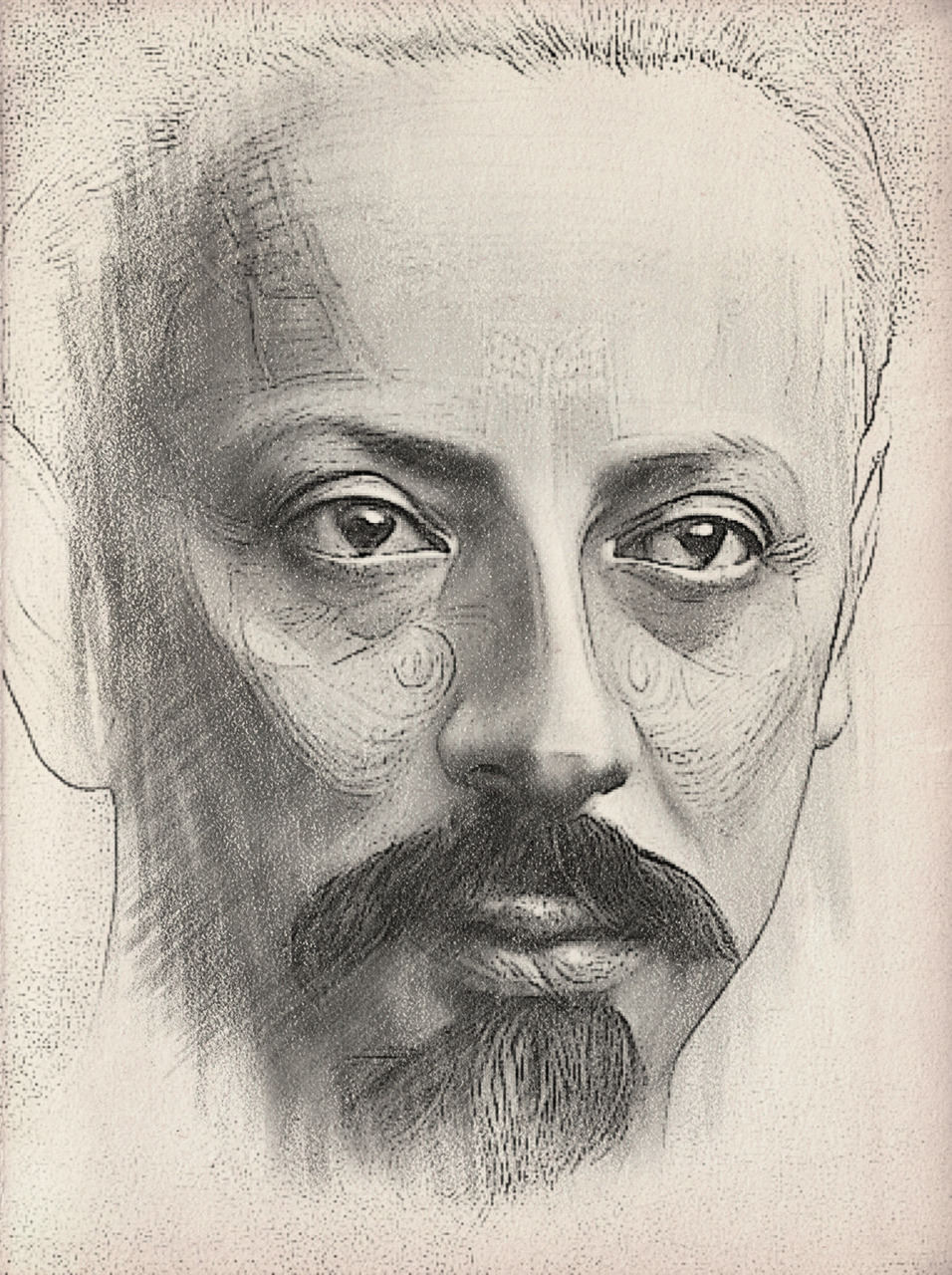

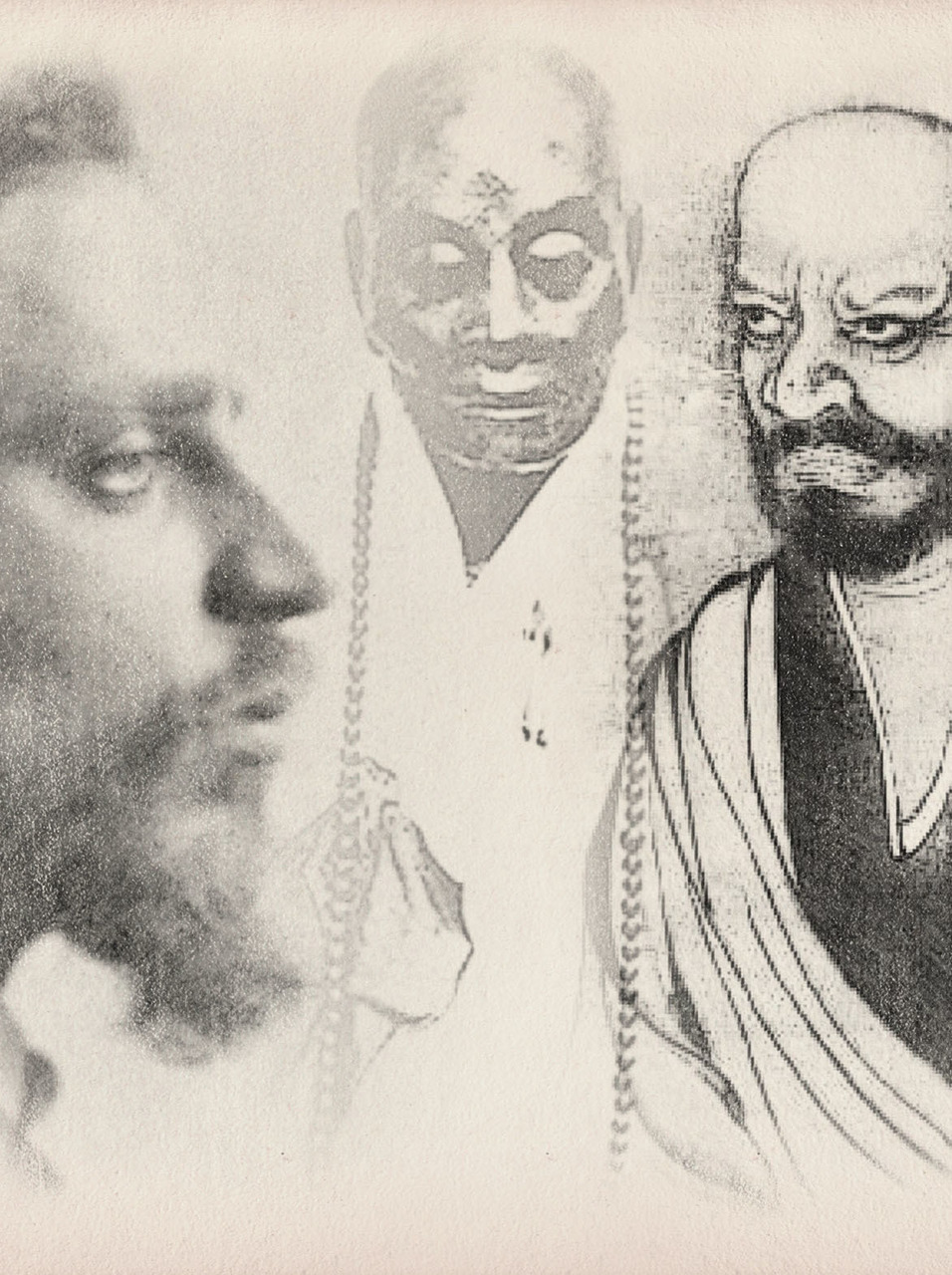

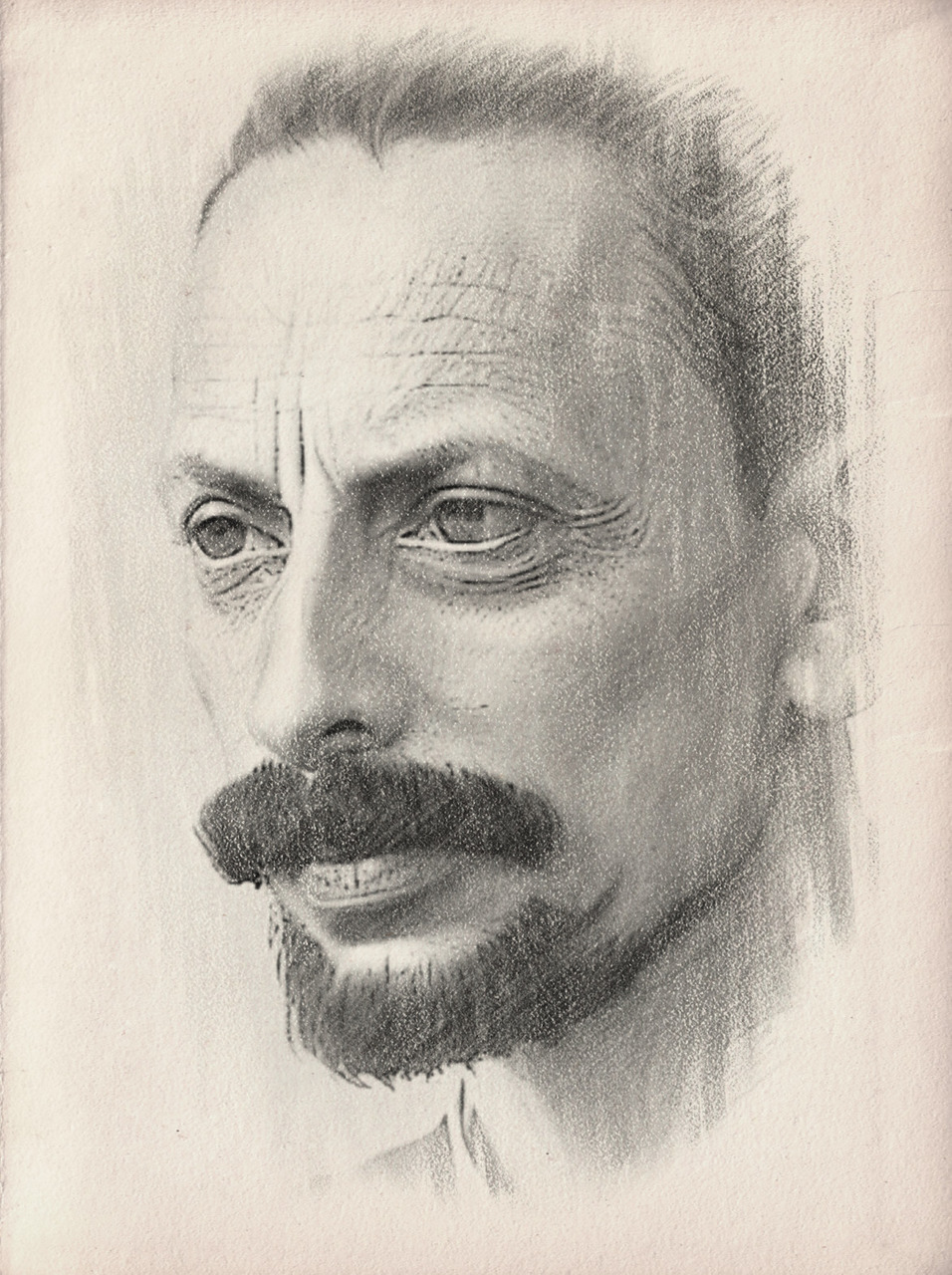

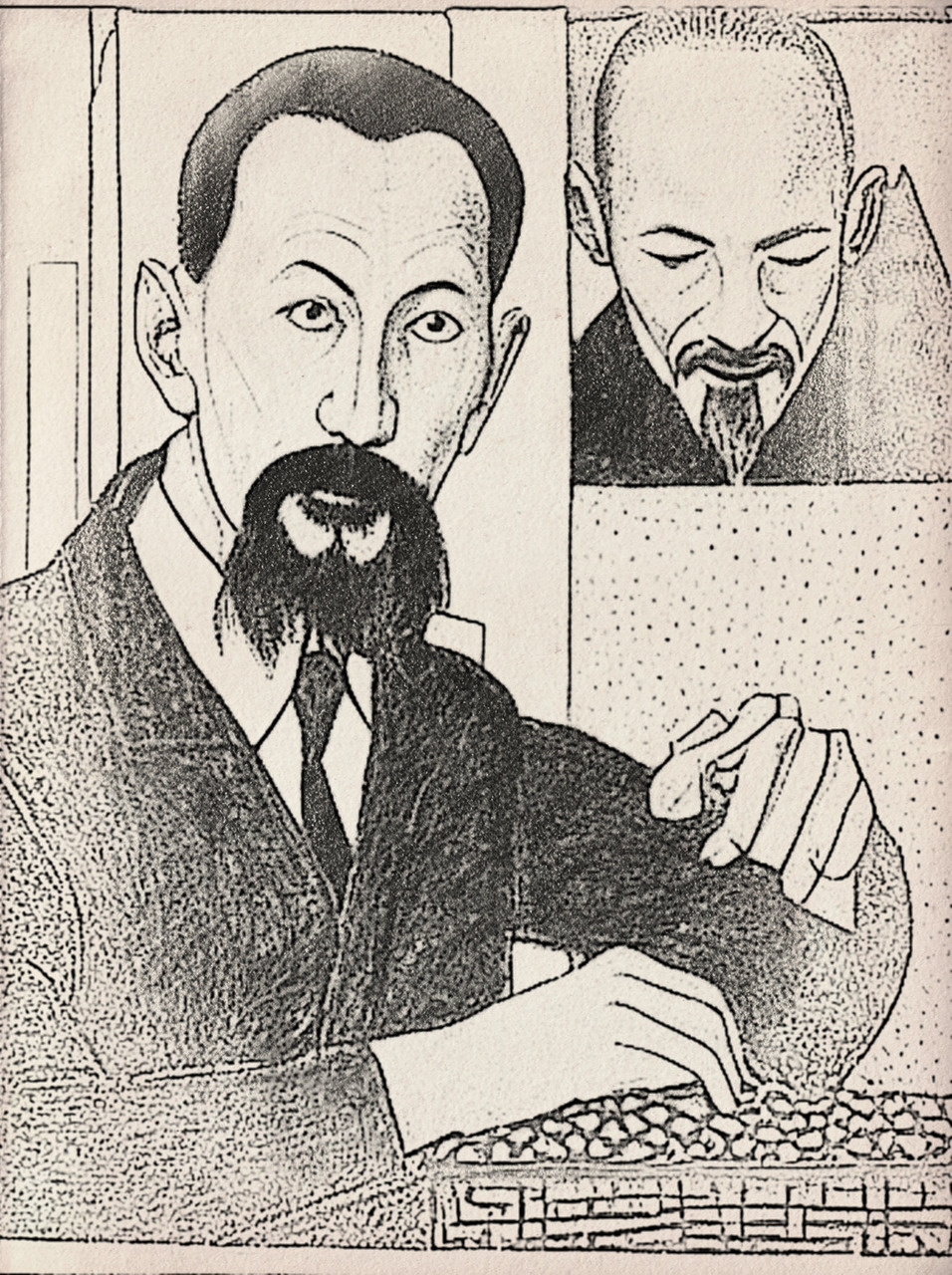

The book contains a large number of images, including some public domain works by Odilon Redon (1840—1916). As for my own drawings, among them the reader will find some fantasy-like Zen portraits of Rilke. One such portrait appears on the cover of the book.

Finally, I would like to point out that the Buddhist theme in Rilke’s work is inexhaustible, and that every facet of this great theme will undoubtedly be a source of surprise and inspiration to the sincere seeker of truth.

There Are No Teachings

…be ye lamps unto yourselves. Rely on yourselves, and do not rely on external help.

— Gautama Buddha

*

•To Be Outside All Doctrine

What I teach requires you to do only one thing — not to accept at face value the mistaken opinions of others.

— Linji Yixuan

Despite Rainer Maria Rilke’s outwardly quiet and prosperous life, his creative journey as a poet was undoubtedly marked by a relentless and intense search for his true self. And in this search, whatever luminaries may have shown the poet the way — Rodin, Buddha or any other great teacher — he always found within himself the spiritual strength to rise above himself and his idol, so as not to fall under the influence of other people’s beliefs and ideas, and to preserve the ability of his mind to remain open and clear.

*

The intransigence with which the poet defended his spiritual independence is evidenced at least by the eloquent fact that even in the last days of his life, when he was already suffering painfully from an incurable form of leukaemia, Rilke asked his doctor to spare him any narcotics so that he could keep his consciousness extremely present and unclouded — ´in all its living fullness´ — and thus die his own death.

´I don’t want to accept death at the hands of doctors, I want to be free.´

In these words of Rilke, written shortly before his death, one hears:

´I do not want to receive knowledge from the hands of teachers; I want to see my own nature.´

*

Not surprisingly, Rilke was opposed to all fixed religious and philosophical systems. Thus, in a letter to the Polish translator Witold von Hulevicz (13.11.1925), we learn of the poet’s rejection of ´Christian meanings´ which, in his opinion, had become fetters on the path to the spiritual liberation of the West. But Rilke was no less categorical in his rejection of dogmatic Eastern traditions, including Buddhist teachings:

´Let us resist the introduction of Eastern traditions: Hindu, Buddhist and others… What they will impose on us one day will not be their strange wisdom (created for them, not for us), but most probably Bolshevism.´

The comparison with ´Bolshevism´ in Rilke’s statement should not surprise the reader: in Western educated circles of the time, this word was often used in a negative sense to emphasise the totalitarian principle of thought.

*

It is unlikely that the ´strange sage´, the great teacher Linji, despite his ardent devotion to the Dharma, would have been outraged by this polemical outburst from Rilke. Rather, the poet would be considered insufficiently radical by this fanatical advocate of ´shock therapy´: it is said that Linji, in his relentless struggle against the widespread false doctrine that was blatantly replacing the living word of his mentors, not only strongly discouraged his disciples from ´traditional´ values by admonishing them:

´To be outside the teachings and outside the tradition,

To rely neither on words nor on symbols.´

*

But he also often accompanied his instructions with blows with a stick — on the heads of his astonished followers. It came to the point that this ´insignificant old man´, who had no regard for the religious sentiments of his flock, did not hesitate to speak frankly unbelievable ´nonsense´. For example, he claimed that ´enlightenment´ and ´nirvana´ were like stakes to which donkeys are tied. And yet he often managed to knock ´enlightenment´ out of these ´donkeys´ with an unexpected phrase like this:

´If you meet the Buddha, kill the Buddha!´

*

However, our protagonists, the Patriarch and the Poet, did not overthrow the ´sacred´ in order to ascend to the throne themselves, did not shame the ´wise of this world´ for the sake of their own self-assertion, did not break with tradition in order to create unprecedented values. By ´acting with all their being ´, their aim was

´to seek man in that sphere where his experience, still synthetic and undivided, appears in all its living fullness…´

— the Poet

´to point directly into the human mind. To see one’s own nature and achieve enlightenment.´

— the Patriarch

*

´Undivided experience´ and ´enlightened mind´, the Poet of Oneness and the Dharma Preceptor, representatives of seemingly so distant eras and cultures, are obviously speaking of the same thing and, as we shall see in their further dialogue, complement each other perfectly — beyond words, secret meanings and any beliefs:

´without the harm that limitations and concessions do to man´,

— the Poet

´without deceiving ourselves with different ´´sacred´´ names´.

— the Patriarch

• • •

TO BE A NEW MAN EVERY DAY

Rilke Talking to a Chan Patriarch

Noble is he who has no obsessions.

— Linji Yixuan

The poet’s statements are quoted from R.M. Rilke’s letter of 28 July 1901 to A. Benois.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.