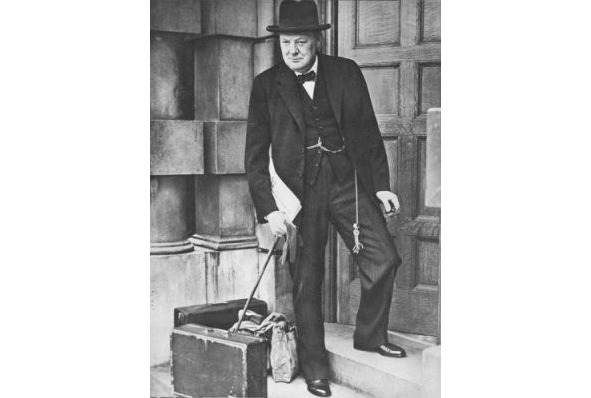

In downtown London, vis à vis the Westminster, a strange monument has been erected to honour the greatest hero of the British history of the 20th century. The bulky, dark figure of the prime-minister Winston Churchill has nothing in common with the gracious ancient heroes. A hunched old man resting on a cane looks grimly at the walls, inside which his speeches not once captivated the minds and hearts of his audience. The sculptor justly judged that Winston Churchill had no need for embellishments, that the bronze grace would become a sort of insult to the character of the man, whose passion and devotion to his country were in contrast to the gracious self-admiration. British people received Churchill exactly this way: True, not decorative, creator of the national history, who had been leading his country through the darkest hours of the war, the peak of the imperial sway, and its final decline.

The brightest British politician of the 20th century had lived a fantastic life, full of intense work – whether at the desk in his office, or at the commanding posts of the world war, or aboard of personal plane, or at the table of diplomatic talks. Whether in the underground bunker, or aboard the battle cruiser, in Teheran, Yalta or Potsdam, that outstanding writer and orator, politician and diplomat always bequeathed – Never surrender!

Churchill is famous not for one, single deed, one battle or campaign, or one achievement. He did not unite his country like Otto von Bismarck, and did not save it from disintegration like Abraham Lincoln; He was a statesman of different virtue, but without him Great Britain would experience the worst perils imaginable.

He served England the way everyone should serve his country – with wisdom, enthusiasm, and respect, but at the same time with cold-blooded calculation, and patience. To the Britons he has forever remained the man, whose personality at the time of peril embodied absolute all-national confidence that Britons never shall be slaves: We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.

Winston Churchill is considered the last politician of the classic imperial era. Thanks to his foresight he already in the beginning of the century properly estimated new technologies and weapons, while the political intuition let him properly evaluate the menace fascism brought to the whole world. Winston Churchill has been known for his “Iron Curtain Speech”, which put the end of the military and political alliance of the Western Allies and the Soviet Union, and opened so-called “Cold War”. But he also has been known for his clear and unequivocal stance, as on 22 June 1941 he, the only world leader, firmly stood by the Soviet Union in its struggle with fascism.

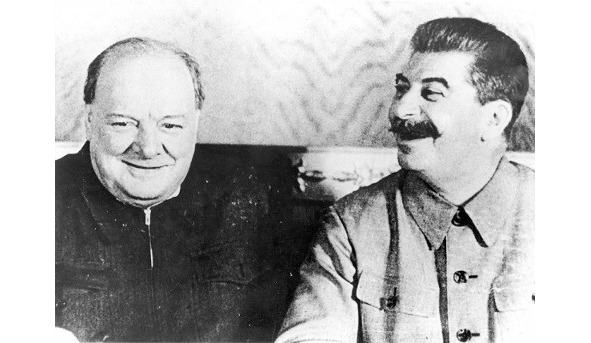

Of course, he resented his country’s losing the leading role in world affairs. In this question he was a true conservative. He hated communism, but loved Cuban cigars, and Armenian brandy. He considered Joseph Stalin an incarnation of evil, but concluded a military alliance with him, and spoke favourably about Stalin in the British Parliament. And Stalin, in his turn, who saw in Churchill the worst enemy of the Revolution, nevertheless gave him this significant opinion:

There have been few cases in history where the courage of one man has been so important to the future of the world.

The youngest man in Europe

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill, a descendant of the famous 18th-century English militaryman and statesman John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, was born in one of the top aristocratic families of Great Britain. Hence his ascension to the upper élite of the British power was partly predetermined, or at least favoured, although his strong, independent personality became a serious obstacle in such ascension. Yet, in the end, it was his personality that eventually brought him to the top.

To a young English aristocrat the path of education had been paved for centuries: first, home education, then one of the privileged schools of Eaton or Harrow, and finally classic education at Oxford or Cambridge university. Yet, the stubborn, undisciplined and often underachieving pupil used to be reprimanded. The doors to Cambridge or Oxford were closed to him; Winston hated mathematics, although he had an excellent memory. In general, he studied what he liked – it is a characteristic quality of creative minds. Eventually, he went to a military college. After two failed attempts. And he joined a cavalry school, which did not require exams in mathematics.

After 18 months of training (mainly horse-riding and shooting), Churchill was commissioned into a hussars’ regiment. He regretted that in the British colonies there were no uprisings that he could gloriously suppress. Later he wrote that his achievements had come from his own efforts. However, in the Victorian England nobility and family connections were of great importance. And his family was famous. It is true that his mother, an early widowed American, used to spend her capitals rather carelessly, but that allowed her and her son to have very influential friends and acquaintances. Anyway, Winston’s ambitious designs would not come true without his active efforts, which sometimes were coupled with substantial obstacles and serious risks.

In 1895 Churchill travelled to Cuba, where local rebels were fighting with the Spanish colonial rule. He published several newspaper articles about his adventures. Then he left for the Indies, but did not find a better occupation than sports and collecting butterflies. The boredom of the garrison life made him turn to reading historical books and philosophical treatises. He kept writing articles for London newspapers, and even published a book in 1897.

The only action Churchill saw in the Indies was suppressing a rebellion of a local tribe, during which he showed courage and inventiveness. So, when the British started a colonial war in Sudan, Churchill used his mother’s connections to join the troops as an officer and war reporter (journalism paid 20 times more than military service). Career officers used to call him a “medal hunter” and “self-promoter”, but Churchill kept writing and did not think about a military career, since it required long and difficult years of effort and risk.

In the autumn of 1899, there was published his two-volume account of the conquest of Sudan – The River War. He honestly described how did his countrymen desecrate Moslem holy places, and how did they scoff the tomb and remains of the leader of the Sudanese uprising – Muhammad Ahmad (Mahdi). He also told the truth about the despicable trick of the British propaganda: to portray the enemy as heinous monsters, who deserve to be mercilessly exterminated. But soon he removed such unflattering opinions about his own countrymen from the second edition of the book. Young Winston started thinking about a political career, and truth became politically incorrect. Nevertheless, he was not elected to the Parliament.

So, Winston Churchill left for South Africa as a reporter of the war with the Boers – the descendants of the Dutch colonists. There the descendant of Duke of Marlborough was taken prisoner – not out of cowardice, but because his unit was encircled and forced to surrender. He managed to escape in a railway carriage; he hid in a mine with the assistance of a local Englishman. A substantial amount of money – £25 – was promised for his capture, but it remained unclaimed: Churchill returned home. At that time the British suffered one defeat after another, and Churchill’s adventures made him a minor national hero. Especially so, that he vividly described his adventures.

Churchill became famous and rich. Now he made it to the parliament. At once he organized with his friend Lord Hugh Cecil a group of young Conservative Party MP’s, who mocked the parliamentary tactics of harassing their own leaders; they called themselves The Hughligans. On that occasion he got a taste for whisky and brandy, as well as sybaritic life style, but ambitions, sound mind, and the willpower helped him to cope with bad habits and build his career. In 1925 he became the Chancellor of the Exchequer – the second person of the government. For that he had to overcome his hatred of mathematics. The next step would be the office of the Prime Minister – his coveted and ultimate goal.

Yet, in 1929 the Great Depression put the world economics on the brink of collapse. To Churchill it spelled a disaster in his political life. He was not invited to form the new government. Not only he had to abandon the dreams about the prime-minister’s office, but even a ministerial portfolio became unreachable. He was shoved to the political obscurity for 11 years. On top of that, there came the crisis in his family life. It seemed that everything was over to Churchill.

In the Parliament he felt at home. He criticized the leaders of his own party in order to annoy them to the point that they would invite him to the government just to get rid of the bully. Churchill was in hurry to climb up the ladder of the political life. But his efforts were all too visible, and his spectacular actions induced worries among his competitors. Once he was excluded from the government, he took this opportunity to pass to the camp of his former political opponents – the liberals. That gained him the pejorative nickname “The Blenheim Rat”, but he deserted the sinking ship of the conservatives just in time: political situation in Great Britain was radicalizing, left-wing forces were gaining more power, and the Conservative Party lost the next election by landslide.

It is difficult to comment on Winston Churchill’s socio-political beliefs. In general, they came down to the desire to preserve the British Empire that “ruled the waves” and many nations, as well as the power of the rich aristocrats in the country. That fully agreed with his personal interests, taste for wealth and power, and hatred of democracy, socialism, and communism. He knew how to go about his capital, and climbed the ladder of personal career even at the expense of the interests of his own political party.

Of course, such a betrayal did not mean a change in his beliefs or advocacy of certain political principles. In fact, such a “ratty” turn-coating between the political camps was not a genuine invention of Churchill’s times. Ruling classes of England assumed the same positions as Churchill did. As the situation in the world and the country changed, so did their policies: sometimes it was needed to win the support of the capital, sometimes of the labour; sometimes they proclaimed free trade, and sometimes introduced regulations to the free market, and so on. In political games opportunists win more often than ideologists. So, Churchill was an opportunist; very clever, intelligent, and when necessary – dishonest political player. Politics was his life, but unlike ordinary careerists, he did not treat politics as a goal, but as the means to achieve the goals. Although in pursuit after the personal goals, he did not neglect national interests.

Churchill had created his own version of the personality cult. He never missed an opportunity to mention his person and emphasize his personal quality (and he really had a lot of them). As many as 40 books about his life and deeds were published during his life. In his career he relied on the whole staff of assistants, and in particular – Sir Edward Howard Marsh, his friend and secretary, whose polymath intellect and artistic taste formed Churchill’s image. All his life Winston Churchill distinguished himself not only with enormous efficiency, but also inalienable ambitiousness.

In his only fiction book Savrola, published in 1900, Churchill said about the main character:

The struggle, the labour, the constant rush of affairs, the sacrifice of so many things that make life easy, or pleasant – for what? A people’s good! That, he could not disguise from himself, was rather the direction than the cause of his efforts. Ambition was the motive force, and he was powerless to resist it. (…) ‘Vehement, high, and daring’ was his cast of mind.

Like many beginners in literature, he characterized himself in that visage – many of his biographers agree on this matter. And yet, he realised the ignoble, selfish nature of his predicaments “he was powerless to resist”. Such predicaments, on top of that paralleled with the clear understanding of his own hypocrisy, pretence, and double-faced care of “good of the people”, were making him psychologically vulnerable in diplomatic duels. Churchill was no fool or rascal, and therefore he could make a sober assessment of his merits as well as his weaknesses.

As early as in 1898, a talented journalist George Warrington Steevens dedicated to him the article The Youngest Man in Europe (at that time Churchill was 24). One can only admire how true his portrait was:

His self-confidence bobs up irresistibly, though seniority and common sense and facts themselves conspire to force it down. (…)

He is ambitious and he is calculating; yet he is not cold – and that saves him. His ambition is sanguine, runs in a torrent, and the calculation is hardly more than the rocks or the stump which the torrent strikes for a second, yet which suffices to direct its course. (…)

It is not so much that he calculates how he is to make his career a success – how, frankly, he is to boom – but that he has a queer, shrewd power of introspection, which tells him his gifts and character are such as will make him boom. He has not studied to make himself a demagogue. He was born a demagogue, and he happens to know it. (…)

For he has the twentieth century in his marrow.

What is more, Churchill, like many Britons of that time, nursed a peculiar British colonial patriotism. After all, his small country ruled at sea, and vast empire. Only between 1880 and 1901 that empire grew from 20 to 33 million sq.km, and its population – from 200 to 370 million people. For each British (37 million) there were 10 slaves in the colonies. They toiled hard to support the empire’s welfare. Therefore, it came quite naturally that Churchill was a sworn enemy of any idea of liberation and decolonization.

Winston Churchill was overheard to say: Politics is almost as exciting as war, and quite as dangerous. In war you can only be killed once, but in politics many times. Most likely he spoke from his own experience. During the First World War, while on the front, he once stood in the trenches, and then stepped down into a shelter. Next moment a German shell exploded right in the place where he just stood. As a politician, he had been “killed” for 11 years. His personality and dignity had been trampled upon many times; many times he had been thrown to the “ash heap of the History”.

He was approaching 70. Churchill is finished – this was the verdict of the British and foreign politicians. Heads of many governments shared that opinion; all but one. Once in a conversation with him, Lady Nancy Astor said: Churchill is finished finally, and she got the reply: I am not so sure. If a great crisis comes, the English people might turn to the old war-horse. The man, who made that unexpected conclusion, was Joseph Stalin.

Winston is back

On 1 September 1939 Nazi Germany attacked Poland; on 3 September Poland’s ally, Great Britain, declared war on Germany. Few hours later a German submarine torpedoed and sank a British passenger liner Athenia in the open sea – the traditional sphere of influence of the British Empire. The Second World War started, and it started in the circumstances most unfavourable to Britain. Those circumstances forced the British prime-minister, Sir Neville Chamberlain, the author of the bankrupt policy of “appeasement” of Nazi Germany, to invite his arch-enemy, Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill, to join the War Cabinet as the First Lord of Admiralty.

In this office Churchill proved to be one of the most efficient ministers, but the overall situation grew grave. When Norway surrendered, and German armoured fist hit France, the House of Commons voted in the new government. Winston Churchill became its head. Thus his life-long dream came true: he became the prime-minister, and on top of that the prime-minister with broad, practically unlimited powers. The grave political and military situation did not discourage him; the people wanted to fight, and fighting was up to his liking.

He was far from being nobody to his enemies. Berlin at that time was already littered with posters and leaflets featuring his portraits or caricatures, and depictions like “Enemy No.1”. There was no idea fantastic enough for the Nazis to abandon plans to eliminate Churchill. But he was not prepared to surrender. As soon as he arrived at the prime-minister’s residence at 10 Downing Street, the first thing he did was to check his gun. The most dangerous fight in his life was about to start.

The British army was in complete retreat. German armoured troops pushed it to a tiny strip of land at Dunkirk, where it nearly escaped annihilation only because Adolf Hitler still nursed hopes that in London capitulationists would take the upper hand, and he ordered to stop the tanks as a gesture of good will. Meanwhile, the British troops were hectically evacuated to the Isles – demoralized and without heavy equipment, but still full of will to fight. Throughout the Great Britain started enlistment for the Home Guard; volunteers were numerous, although they seldom had any military experience, and their armaments were scarce if any. But the advocates of concluding peace with Germany were still in a tiny minority, for such an act would simply mean the defeat in war.

Still, British ships carrying war materials were sinking in the Atlantic Ocean at a frightful pace; at the heart of the British naval base in Scapa Flow, the battleship Royal Oak was sunk by a single daring German submarine. Soon there started air bombings of Britain. Coventry was wiped out of the face of the Earth. London was burning – borough after a borough.

Yet, Churchill had braced for furious activity. He was building a new army, switching the industry to the war production, and nationalizing the aircraft factories. It seemed that on those days he was everywhere: in the ruins of London and anti-aircraft batteries, on the airfields and ships. That was the “finest hour” of his life and his political career. British airmen, shot down not once, were taking off again in their hurriedly repaired planes for new victories. The commander of the German Air Force, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, was in dismay, and Hitler was furious: According to the reports of their intelligence, the Royal Air Force should have already been destroyed. The German landing on the British Isles was delayed. The Battle of Britain was won. But for how long? Churchill dismissed the eventuality that the Germans might occupy England, but the odds were still against him.

Hitler would not give up either. Again he hinted at the chance of getting away: In May 1941 there took place the mysterious flight of his first deputy, Rudolf Hess, to Britain. Hess brought with him Berlin’s conditions for a peace accord: division of the spheres of influence. Germany would have continental Europe, and England would have its empire.

Churchill faced a dilemma: To follow the path of the French Marshal Philippe Pétain, one of the victorious commanders of the First World War, who saved for France its colonial empire at the price of becoming Hitler’s humble servant in Europe, or to continue the war, maybe even with Joseph Stalin in further perspective. But Stalin at that time had the non-aggression treaty with Germany. What if he preferred to become Germany’s ally? That would spell a disaster to Great Britain and the whole British Empire.

To Churchill, Adolf Hitler was ideologically closer than Joseph Stalin. In 1920's Sir Winston observed with great interest, and even with some sympathy, the German Nazi movement, which called to “strangle Bolshevism in its cradle”. Uncompromising anti-communism of a German rowdy impressed the English lord.

But in the 1930's Churchill changed his position radically, as the German Führer posed a clear and real threat to the British Empire as well. He started attacking the British friends and sponsors of the Nazism, and became a frequent guest in the Soviet embassy in London. He was even willing to support the People’s Front, despite the fact that the communists took part in its works.

Of course, that radical change came out not from any sudden switch to the leftist ideology, but from his desire to preserve the British Empire as he knew it at the time when European fascists were preparing to tear it apart, and their Japanese ally was rattling arms at the very doors to the British colonial possessions in Asia. Hitler embarked on the policy of the territorial aggrandizement in Europe, and eliminating Great Britain as a factor that mattered in the European affairs. Benito Mussolini occupied Abyssinia (Ethiopia) and some British colonies in East Africa, and was looking forward to capturing Egypt and the Suez Canal – the main sea route of the British Empire.

So, Churchill was shifting troops and tanks back and forth between the British African and Asiatic colonies; he stopped the Italians, pushed them back, and captured most of the Italian possessions in Africa. But then Hitler came with the aid to his Italian ally. The African Corps under the command of Gen. Erwin Rommel was sent to Africa. Italian navy and air forces, reinforced by the German squadrons, had besieged Malta – the main British military base on the way between Egypt and Gibraltar. Fierce battles flared up in the Mediterranean Sea.

To Churchill, the choice was not an easy one. He had three options. The first option was to save Britain with all her colonies and dominions, but at the price of the devastating war. The second option would be to accept the deal with Hitler under the threat of losing the empire, and reduce his country to the marginal level of importance. The third option was to manoeuvre to have put Germany and the USSR at odds, hoping that the two countries he hated would weaken each other in mutual war.

Of course, the third option would be the most favourable of all. But its realization would be the most difficult as well. Both Hitler and Stalin were wise and cautious leaders, who did not fancy pulling chestnuts out of the fire with their hands for someone else’s interests. They both understood that a clash of two giants like Germany and the USSR would cause a long and devastating war. And the victory in such a war requires substantial advantages.

Germany saw that advantage in the aggrandizement of the controlled territories, conquering other countries and nations, and exploiting their resources for German goals. The USSR saw the advantage in the consolidation of the unity of the multinational country, utmost mobilization of the resources, and searching for potential allies in the inevitable war with the Third Reich. Only Great Britain and the United States could become such allies. So, Stalin did everything possible to hint to Churchill, while maintaining correct relations with Hitler, that the USSR had no plans to dismember the British Empire. On the other hand, siding openly with Churchill against Hitler was out of question: that would require more thorough preparations. Moreover, Stalin too was concerned about the national interests of his country. And the national interest of the first socialist state in the world was to have capitalist opponents fighting with each other.

His enemy’s ally

In April 1940 German forces overcame Denmark and Norway. In May surrendered Holland and Belgium, and France surrendered in June. At the end of 1940, Italy invaded Greece, and Churchill tried to mount a Balkan front made of Greek, Yugoslav and Turkish divisions, but Belgrade and Athens fell at the beginning of 1941, while Turkey chose to maintain neutrality and correct relations with Germany. Crete held longer, but eventually, German airborne troops beat there prevailing Anglo-Greek forces.

The United States were helping Britain, but with a very peculiar help. For example, in exchange for 50 obsolete destroyers, they asked main British naval bases in the Caribbean region, and major economical concessions in Canada. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had to consider the strong isolationist opposition in the Congress and in the country, evaded more active engagement in the on-going war. Meanwhile, American monopolies utterly exploited the favourable situation, and started taking over markets in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The British Empire got caught between two fires: Fascist powers were tearing it apart on the fronts of the world war, while American allies were back-stabbing it in the rears. Winston Churchill was flouncing between the need to defend England’s independence and desire to preserve its colonial empire. He was a great patriot of his country, and had ambitions to be a great statesman. He needed an ally – a third power, independent from the USA, and able to stand against Germany. Only that third power could save Great Britain.

On 22 June 1941 in the morning he was still in the bed, when the urgent news was brought to him of Adolf Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union. Later Churchill wrote that it gave him an important relief. He immediately called BBC and announced an important broadcast on its waves in the evening. Sir Winston spent the day composing his statement. He had to abandon the anti-communist rhetoric and offer co-operation:

We have but one aim and one single irrevocable purpose. We are resolved to destroy Hitler and every vestige of the Nazi regime. From this nothing will turn us. Nothing. We will never parley; we will never negotiate with Hitler or any of his gang. We shall fight him by land; we shall fight him by sea; we shall fight him in the air, until, with God’s help, we have rid the earth of his shadow and liberated its people from his yoke. (…)

It follows, therefore, that we shall give whatever help we can to Russia and to the Russian people. We shall appeal to all our friends and Allies in every part of the world to take the same course and pursue it as we shall, faithfully and steadfastly to the end.

If Hitler ever feared anybody, that would be Stalin and Churchill. Now those two had allied against him.

The British prime-minister’s speech was published in the Pravda newspaper, but no direct contacts between two leaders of the fighting countries followed. On 7 July Churchill sent a personal message to Joseph Stalin, and three days later – another one, with the first draft of the plan of mutual help. Answers did not follow.

It was not until 17 July that Stalin sent his first letter to Churchill. And that is quite understandable. On 22 June most of the Soviet air forces were destroyed on the airfields; in Byelorussia, two Soviet armies perished in the gigantic Grodno-Belostok cauldron, and in the approaches of Leningrad, on the River Luga, the Russians stopped Field-Marshal Wilhelm von Leeb’s advancing tanks literally with their dead bodies. In those critical circumstances, Stalin did not want to make an impression that the British prime-minister was throwing him that straw to clutch like a drowning man.

Moreover, in the beginning of the invasion, the German propaganda spread rumours that Stalin was in prostration, and prepared to flee the country – the lie that Nikita Khrushchev picked up later. Indeed, it was the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Vyacheslav Molotov, who broke the news about the war. Stalin went public with his speech on 3 July. Why? The answer is simple – he had no time for speeches (although it was him, who suggested to Molotov the point of his speech: “Ours is the righteous cause. The enemy shall be defeated. Victory will be ours.”) Some historians suggest that Stalin hoped to announce a swift victory over the fascists, but it is hard to believe that the Soviet leader was that naïve. The first days of the war revealed the grave situation on the fronts, and communication with many armies and divisions was broken. Besides, the Soviet command was well informed about the strength of the German Wehrmacht and its satellites.

Also, one should not ignore the passage from Churchill’s speech that stated:

The Nazi regime is indistinguishable from the worst features of Communism. It is devoid of all theme and principle except appetite and racial domination. It excels in all forms of human wickedness, in the efficiency of its cruelty and ferocious aggression. No one has been a more consistent opponent of Communism than I have for the last twenty-five years. I will unsay no words that I’ve spoken about it.

Obviously, Stalin had no reason to trust such a “sworn friend”, and was not in a hurry with an answer. It was not until he had the defences stabilized that he opened contacts with Churchill on equal foot. There was concluded the Anglo-Soviet alliance. Members of Churchill’s War Cabinet expressed the opinion that the fall of the Soviet Union was just a matter of weeks. But he firmly insisted that the USSR must hold at least a year or longer. England, cornered from the air and the sea, was interested in a protracted war in the East. But that required material aid to the USSR. So, that aid was delivered, first via Iran, and then along the sea routes to Murmansk and Archangel.

Iran, after all, became the first ground of the Anglo-Soviet co-operation, and the first ground where their interests clashed. As the pro-German sympathies in that oil-rich country posed a substantial threat to the rears of the Soviet Union and the British Empire, Soviet and British troops occupied Iran in August 1941. At the end of September 1941, an Anglo-American mission arrived in Moscow. The minister for aircraft production, William Maxwell Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, who represented Great Britain, during a conversation with Stalin suggested that some British troops might perhaps be sent to the Caucasus to block a possible German breakthrough (old British dream – the oil of Caucasus). There is no war in the Caucasus, Stalin replied, but there is in the Ukraine.

The British were not prepared to fight the Germans in the Ukraine, so the question was closed. Stalin also expressed his disappointment with meagre supplies of the Western military equipment. But the representatives of Great Britain and the United States refused to increase the supplies. That information promptly reached Berlin, and the German propaganda announced: Western plutocrats will never come to terms with the Bolsheviks! The same evening, when Stalin met Beaverbrook and the American envoy Averell Harriman again, he mentioned the Nazi announcement and added with a cunning smile that it was a convenient moment to show what a liar Goebbels was. Stalin’s attitude impressed Western envoys. He was calm, confident about the victory, demonstrated that he was a trustful ally, and expected the same from the USA and England. The envoys agreed to increase military supplies.

Meanwhile, the fates of the war were hanging on the pitched battle in the fields near Moscow. Stalin was bringing strategic reserves to launch a counter-offensive, which started at the beginning of December 1941. Churchill learned about the Germans’ first major defeat on the East front aboard the battleship Duke of York taking him to the United States. He immediately wired to Stalin:

I cannot tell you how relieved I am to learn daily about your remarkable victories on the Russian front. I have never felt so confident in the outcome of the war.

The British foreign minister, Sir Anthony Robert Eden, who at that time was in Moscow, telegraphed his prime-minister: Stalin spoke very warmly of you.

Later, in his memoirs, Eden admitted that he experienced less satisfaction with the Red Army’s success, and more worry about the consequences of Germany’s defeat to the British interests. In the mid-December 1941, he was allowed to visit areas liberated by the Soviet troops around Klin. He was impressed by the sight of the piles of destroyed German equipment. He also described a conversation with three wretched German POW’s, but did not say a single word about the sufferings of the local civilians.

Also, Eden was impressed by Stalin’s calm confidence. When the British foreign minister remarked that there was too little ground for optimism, for the war with Germany would be long and difficult, since Hitler was still near Moscow and it was a long way to Berlin, Stalin answered: The Russians have been in Berlin twice. And will be there a third time.

It was that calm confidence in the victory of the USSR that worried the leaders of the Western democracies and Churchill personally. On that occasion Churchill’s dark side in the relations with the Soviet Union had manifested itself, especially in the question of the military supplies – the British and the Americans delivered lesser quantities of the military equipment than agreed, and very often they delivered obsolete equipment.

Second front

On 22 June 1941 Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. The British minister of aircraft production, Sir John Moore, 1st Baron Brabazon of Tara, expressed on that occasion the hope that Germany and the USSR would destroy each other. And Harry Truman, a US senator, spoke even more blatantly in the interview given to the New York Times on 24 June 1941:

If we see that Germany is winning, we ought to help Russia, and if Russia is winning, we ought to help Germany, and that way let them kill as many as possible.

Sir Winston Churchill was definitely smarter, more cautious, more cunning, and better experienced than those otherwise rather narrow-minded individuals. After all, John Moore Barbazon lost his office to his careless talk (although Truman later became the vice-president and the president of the United States). Churchill never took the liberty, at least before 1943, to speak in the same tone. But his practical deeds fit the same philosophy. Despite of the solemn promises to open the second front in France before 1942, he shifted the British war effort to the Mediterranean Sea and North Africa. There were more or less objective reasons to do it, of course, but effectively the Red Army was left alone facing the bulk of the German Wehrmacht. And although Joseph Stalin since the outbreak of the war with Germany insisted on opening the second front in the West, Churchill by all means postponed the decision in such an urgent matter.

In December 1941 Japan attacked the United States, putting the end of their neutrality. Although American forces were chiefly engaged in the battles in the Pacific Ocean, there emerged an opportunity to open the second front in Europe in 1942. The US president Franklin Delano Roosevelt promised that to Stalin, but Churchill again used all his influence to delay the realization of that promise. And he did it in the most critical phase of the war.

Encouraged by the promises of his Western allies, as well as the success of his armies in the battle of Moscow in the winter 1941/1942, in the spring Stalin launched a new major counter-offensive on Kharkov. Yet, the Anglo-American inaction in the West let Adolf Hitler to transfer more troops from the west to the east, and turn the crisis on the East front into a strategic success: The Germans surrounded Soviet armies advancing on Kharkov, captured tens of thousands of POW’s, occupied rich areas of south-eastern Russia, and developed their offensive to the Caucasus and Stalingrad. And right at that time, the British suspended convoys with war materials to Murmansk and Archangel. The Soviet-British relations worsened. The British ambassador in Moscow wrote to the Foreign Office that deterioration in the Anglo-Soviet relations would be fraught with long-term negative consequences. The telegram discouraged Churchill.

The most fearful turn of the events to him could become conclusion of a peace agreement between the USSR and Germany. Those two military giants were fighting with changing fortune. In the winter their forces almost equalled, but the Germans’ summer offensive of 1942 resumed with renewed power. They captured Crimea, approached Caucasus, and were about to cross the Volga. Goebbels’ propaganda already announced the collapse of the Red Army.

Hitler’s initial plans foresaw occupation of the Baltic Republics, Byelorussia, Ukraine, Crimea, Caucasus, and the Volga region – the most fertile and industrialized regions of the USSR. He was close to the success, and Churchill was afraid that Stalin might try to save the rest of the country, mostly in Asia, for himself at the price of recognizing Hitler’s conquests. And having concluded the peace in the East, Germany could transfer the bulk of its armed forces to the West.

Such considerations, such a fear of a peace accord between Hitler and Stalin at the decisive phase of the war, demonstrate how poorly Churchill estimated the mentality of the Soviet leader and the Soviet people. To Stalin communist ideals were not merely a tool in demagogic feuds with his adversaries; it was a disguise, under which he consolidated the patriotic feelings of various nations. In this respect, Churchill was mistaken as much as Hitler. And for the same reason they both underestimated the will of the peoples of the Soviet Union to win.

Churchill, used to political manoeuvres and changing the party membership for his personal, ambitious gains, believed that he could expect the same from Stalin, especially in such a perilous time. Moreover, his own cunning and unprincipled position in the question of the “second front” would be shattered, had Hitler and Stalin made a mutual agreement.

In May 1942 Molotov visited London and Washington, where he conducted talks about the Western allies’ help to the Soviet Union. The president of the United States confirmed his will to open the second front in Europe as soon as in the summer. Yet, Churchill continued to answer evasively and vaguely. His goal was to delay as much as possible the direct encounter of the British troops with the powerful German armed forces. (After all, he succeeded in this respect – Great Britain became a winner in the Second World War at relatively small cost; even the American losses were significantly bigger.)

It is difficult to say how much Roosevelt was sure about his promise to open the second front so soon. It is very likely that he was sincere. In his cable to Churchill from 6 July 1942 he admitted that his greatest concern was the situation on the Russian front. Therefore, he was afraid of the worst; if not the collapse of the USSR, then at least its capitulation, and he hinted that such an eventuality was not acceptable.

Meanwhile, Churchill continued dodging. He handed to the Soviet foreign minister the memorandum, which read:

We are making preparations for a landing on the Continent in August or September 1942. As already explained, the main limiting factor to the size of the landing force is the availability of special landing-craft. Clearly however it would not further either the Russian cause or that of the Allies as a whole if, for the sake of action at any price, we embarked on some operation which ended in disaster and gave the enemy an opportunity for glorification at our discomfiture. It is impossible to say in advance whether the situation will be such as to make this operation feasible when the time comes. We can therefore give no promise in the matter, but provided that it appears sound and sensible we shall not hesitate to put our plans into effect.

It looked like the Britons were prepared to waver unwaveringly to gain solutions sound and reasonable to them. The words about the preparations for a landing on the continent were a pure lie; not because the landing would not happen, but because Churchill knew it before he wrote the memorandum.

The point is that the representatives of the governments of the USA and Great Britain discussed the question of the “second front” in April 1942. An officer of the United States War Department, Lieutenant-Colonel Albert Coady Wedemeyer, who took part in the conference, later recalled:

The British were masters in negotiation – particularly were they adept in the use of phrases or words which were capable of more than one interpretation. Here was the setting, with all the trappings of a classic Machiavellian scene. I am not suggesting that the will to deceive was a personal characteristic of any of the participants. But when matters of state were involved, our British opposite numbers had elastic scruples. To skirt the facts for King and Country was justified in the consciences of these British gentlemen. (…) What I witnessed was the British power for finesse in its finest hour, a power that had been developed over centuries of successful international intrigue, cajolery and tacit compulsions.

Obviously, it was the British prime-minister, who set the British for such a duplicitous discussion of the very important military and political question. After all, Churchill himself praised such an “art” with esteem: I had no idea of the enormous and unquestionably helpful part that humbug plays in the social life of great peoples dwelling in a state of democratic freedom.

The definition of the “humbug” is a person or object that behaves in a deceptive or dishonest way, often as a hoax or in jest. The term was first described in 1751 as student slang, and recorded in 1840 as a “nautical phrase”. It is now also often used as an exclamation to mean nonsense or gibberish. Therefore, according to Churchill, possibility to cheat on allies, and on his own nation, without bearing any consequences, is a great achievement of the “democratic freedom”, as the lie disguised in specious pretexts may be interpreted in many ways.

And so, in his relations with Stalin in difficult times, Churchill chose the policy of cunning, deception and procrastination. Of course, there were objective reasons for that. The British Empire was falling apart; in 1942 it lost some of its colonies. In Asia, the Japanese menaced Indies, and their air forces attacked Ceylon and Australia. In the Atlantic Ocean, German submarines applied the tactics of “wolfpacks” to sink one British ship after another. But Churchill’s grandiloquent words that he was boldly walking in the world being in close and friendly relations with “a great man in whom we can trust whose fame has gone out not only over Russia, but the world” were in diametrical contradiction with his deeds, especially in the matters of the landing of the Anglo-American forces in France.

Hitler amassed 75% of his forces on the East front. In the west he had only 36 divisions, only a few of them deployed on the Atlantic coast. Those were convenient conditions for opening the second front. Stalin refused to recognize air and naval operations for “second front”. He demanded a landing in France. The British public opinion too urged Churchill to open second front and relieve the Soviet Union.

And then Churchill staged a limited action in Dieppe, where landing Allied troops were beforehand sacrificed in order to prove the difficulties of a landing in France. Even a success at Dieppe could not open any “second front”, because that would require more troops, more equipment, and a bigger fleet of landing crafts. Since all that had not been done, it meant that Churchill had not been planning major operations of the Anglo-American forces on the European continent. Instead, he imitated activity as he proposed another landing in northern Norway. Yet, all Churchill’s military and political stratagems were thought do deceive not so much the enemy, but rather the ally. He did everything possible to have the USSR fighting alone with Nazi Germany, and simultaneously to keep it from a separate armistice with promises of the Anglo-American support.

When it became obvious that there would be no Allied landing in France in 1942, Churchill could let it known to Stalin through diplomatic channels. However, he anticipated a justifiably negative reaction, so he decided to meet the Soviet leader in person. This is how the British prime-minister remembered his historical meeting with Stalin in August 1942:

I reached the Kremlin, and met for the first time the great Revolutionary Chief and profound Russian statesman and warrior with whom for the next three years I was to be in intimate, rigorous, but always exciting, and at times even genial, association.

However, he was flying to Moscow not with a genial design, for he perfectly realised how unsuitable was his role of a trickster, forced to continue his manoeuvres and cheats. He admitted it openly:

I pondered on my mission to this sullen, sinister Bolshevik State I had once tried so hard to strangle at its birth, and which, until Hitler appeared, I had regarded as the mortal foe of civilised freedom. What was it my duty to say to them now? (…) Still, I was sure it was my duty to tell them the facts personally and have it all out face to face with Stalin, rather than trust to telegrams and intermediaries. At least it showed that one cared for their fortunes and understood what their struggle meant to the general war.

In fact, the honourable gentleman dissembled. Even after Hitler appeared, he did not cease to regard the USSR as the mortal foe of civilized freedom. British politician Emrys Hughes thus characterized Churchill’s antagonism with Hitler:

It is likely that political ambition was the most important factor which led Churchill to become a Hitler-baiter and to attempt to rouse Britain against the Nazis. (…) His antagonism seems to have been born of fear that Germany might become too powerful under the Nazis and challenge British dominance in Western Europe and of the recognition that rousing Britain against Hitler might be the only way in which he could once again gain an important public post.

Another passage by Emrys Hughes aptly characterizes relations between Churchill, and Hitler and Stalin:

Had Hitler been concerned only with preaching a holy war against Russia, Churchill could not logically have quarrelled with him. For he was as bitterly anti-Bolshevik as Hitler or Goebbels or any of the school of anti-Russian hate merchants and propagandists who exploited the Red bogey in their political warfare. Winston had been a pioneer and a distinguished master of this propaganda from the beginning, long before the Russians or the rest of Europe had heard of Goebbels.

In 1937 Churchill thus spoke about the Führer:

One may dislike Hitler’s system and yet admire his patriotic achievement. If our country were defeated I hope we should find a champion as indomitable to restore our courage and lead us back to our place among the nations.

At that time he did not take Stalin seriously, as a worthy statesman, whose example might be useful in difficult times: Too big were the class contradictions between them. They both understood the concept of democracy differently, and their concepts were mutually exclusive. That is why Russia to Churchill seemed sullen and sinister. Especially so that he was travelling to Moscow in order to extricate himself from a shameful situation, in which he put himself before Stalin.

When Churchill met Stalin

Churchill’s mission in Moscow was difficult and rather unpleasant. Especially so that he while being the older one, had to come to younger Stalin. And Stalin for sure knew and remembered what Churchill said to Vyacheslav Molotov just three months before: British nation and its army were eager to engage the enemy as soon as possible and thereby help the Soviet army and its people in their glorious struggle. And now he was bringing a refusal.

On 12 August 1942, as he arrived in Moscow, Sir Winston visited the Kremlin the same evening. Together with him were the special envoy of the US president in Europe, William Averell Harriman, and the new British ambassador in the USSR, Sir Archibald Clark Kerr. Before the meeting, Joseph Stalin told his foreign minister: Nothing good can be expected.

When Churchill entered, gazing around the relatively small office, Joseph Stalin stood at the table without a smile, and then approached the guest, stretched his hand that Churchill shook with energy, and said in a hoarse voice: Welcome to Moscow, Mr. Prime Minister.

Churchill, with a forced smile, assured him that he was glad to have the opportunity to visit Russia and to meet the country’s leadership. He was unsettled. As they sat at the table, Stalin asked Churchill how he felt after a long flight, and if he had a comfortable accommodation. Then he briefly presented the situation on the fronts:

The news is not good. The Germans are making a tremendous effort to get to Baku and Stalingrad. I don’t know where they had been able to get together so many troops and tanks and so many Hungarian, Italian and Rumanian divisions. I’m sure they have drained the whole Europe of troops. In Moscow the position is sound, but I can’t guarantee in advance that we will be able to withstand a German attack. In the south we have been unable to stop the German offensive.

So, Stalin sent a clear message to the British prime-minister, how urgent was the matter of the “second front” at that time. Churchill took that opportunity to show his competence, and expressed certainty that without superiority in the air the Germans would not undertake a major operation in the sector of Voronezh, or farther in the north. Stalin objected:

This is not so. Due to the long-stretched front, Hitler is quite able to allocate twenty divisions and to create a strong offensive fist. Twenty infantry divisions and two or three armoured divisions will quite suffice for such a task. Given what Hitler has now, it is not difficult to allocate such a force. I couldn’t imagine that the Germans could collect so many troops and tanks anywhere in Europe.

Indeed, the Nazis controlled most of Europe with its human and industrial resources. More than one-third of the population of the USSR and many industrial centres found themselves in the occupied territories. It was extremely difficult to endure the enemy onslaught. Stalin was sincere. Now there came Churchill’s turn to do the same. He asked:

“I believe you would like me to revert to the question of the second front?”

“As you wish, Mr. Prime Minister.”

“I came here to talk about real things in the most sincere manner. Let’s talk like friends…”

And Churchill began to expound at length the reasons, for which the landing in France this year was not appropriate. Stalin, who had begun to look very gloom, patiently listened to him, and then interrupted with the direct question: So, if I understood you properly, there will be no second front this year?

After an awkward pause Churchill started explaining that a landing on the French coast required thorough preparations to make it big and successful next year, in 1943. In the nearest future, nothing significant could be done; any amphibious operation would be doomed to fail, and would not help the Soviet ally. Churchill asked Harriman to present considerations of the American president. They boiled down to the confirmation of abandonment of the previous promises, because an operation in France seemed too risky. Stalin became restless, and answered slowly:

My view about the war is different. A man, who is not prepared to take risks, can’t win a war. Why are you so afraid of the Germans? They are not super-humans. My experience shows that troops must be blooded in battle. If you don’t blood your troops, you will have no idea what their value is. The opening of the second front now is the opportunity to test the troops under fire. That’s what I would have done on if I were British; just don’t be afraid of the Germans.

Stalin was naturally disappointed and irritated, and he perfectly understood that bullying the British prime-minister would not open a “second front” in a month or two. It was too obvious that Churchill had already made his decision, with the full support of his American partners. But Stalin just would have not been himself, if he had not put Churchill in a humiliating position. He felt he had the right to do so, as he was the supreme commander of the armies fighting exceptionally dramatic and bloody battles, while his allies preferred to observe the clash from a distance, sparing their people, and building up their resources.

Insulted Churchill puffed his cigar, and recalled how in 1940 England alone stood against the Nazi power, while Moscow maintained its neutrality at the price of good relations with Berlin. And yet, Britons did not flinch, and endured; Adolf Hitler did not dare to invade the Isles, as he got a good repulse from the gallant Royal Air Force.

Then Stalin reminded him, that although England indeed faced Germany alone, it in fact preferred to procrastinate, and gave away one European country after another. England did not come to aid Poland despite the alliance between the two countries; England half-heartedly reacted to the invasion of Denmark and Norway; England was reluctant to engage against the Italo-German operations in the Balkans. Yes, the British air force and navy were active, but that was too little to win the war.

Churchill objected: Hitler was afraid to cross the English Channel. Such an operation is not as easy as it seems. One needs to prepare it thoroughly.

In return, Stalin answered that there was no analogy. The landing of Hitler in England would have been resisted by the people, whereas in the case of a British landing in France the people would be on the side of the British. Churchill argued pointed out that it was all the more important therefore not to expose the people of France by a withdrawal to the vengeance of Hitler and to waste them when they would be badly needed in the big operation in 1943.

Then there came the pause. Stalin realised that he was not in the position to force his allies to engage more closely in the war with the Germans. He even expressed it this way, emphasizing that the arguments of the British prime-minister did not convince him. Churchill realised that the most unpleasant part of his mission was over, and switched the conversation to the question of the strategic bombings of Germany. Stalin expressed his satisfaction, as he said that it was very important to deal the blows not only to the German industry and transport infrastructure, but also to the morale of the German people. Therefore, he concluded, British air raids were of tremendous strategic importance.

Courtesy and dignity prevailed, concluded Churchill later. The moment had now come to bring “Torch” into action. That became the second front in North Africa. Churchill particularly emphasized the vital need for secrecy. At this Stalin grinned and said that he hoped that nothing about it would appear in the British press.

Now the Soviet leader changed the tactics of negotiations. As Stalin realised that the Allies in no way would renounce their plans, he stopped demonstrating his irritation, and held his emotions. It was needed to avoid giving to the Germans hopes for discords among their opponents. Sarcastic remarks about the British being afraid of the Germans were made to strike Churchill out of equilibrium, and provoke his response, in which an irritated man could say too much, and could reveal the feelings he would prefer to conceal.

It is remarkable that Stalin not for a moment tried to press the Allies with hints to a possibility of concluding a separate peace accord with Germany. Such a diplomatic stratagem would be justified, and it would put Churchill in a very difficult position. Yet, Stalin chose to play honestly and openly. He received the news about the operation Torch favourably, and immediately recounted four main reasons for it:

At this point Stalin seemed suddenly to grasp the strategic advantages of “Torch”. He recounted four main reasons for it: first, it would hit Rommel in the back; second, it would overawe Spain; third, it would produce fighting between Germans and Frenchmen in France; and, fourth, it would expose Italy to the whole brunt of the war.

I was deeply impressed with this remarkable statement. It showed the Russian Dictator’s swift and complete mastery of a problem hitherto novel to him. Very few people alive could have comprehended in so few minutes the reasons which we had all so long being wrestling with for months. He saw it all in a flash.

And so, the first, four-hours long, meeting between Churchill and Stalin was going unevenly, sometimes emotionally, but ended in a friendly atmosphere. Nevertheless, the British prime-minister was not sure if the Soviet leader, taking into consideration the grave situation on the fronts, would not pick up the question of the “second front” in Europe again. So, on the next day, as he met Molotov in the Kremlin, Churchill spoke at lengths about the advantages of the operation Torch. At the end he concluded: