Бесплатный фрагмент - Mascotherapy: Briefly about the Main

This first English translation of Mascotherapy is like Noah’s dove, sent in search of new land — with hope.

Beginning

Dear friends!

I have devoted half of my life to refining and developing the method first proposed by G. M. Nazloyan. Mascotherapy is not just art therapy and not merely the sculpting of a face. It is a path where art, psychology, and the exploration of deep consciousness converge.

You take clay in your hands, look into a mirror — and suddenly you realize: this is not just material, but the beginning of a true conversation with yourself. With the one you once lost, forgot, or have not yet met.

Mascotherapy does not simply remove social masks — it makes them conscious. You begin to see the roles you play, to understand where they came from and why. The mask becomes not an enemy, but a sign — a step toward recognizing: where the mask ends, and where your true face begins.

Here, you do not hide behind familiar roles. Here, you reclaim your real face — not the one others are used to seeing, but the one born from the depths of your soul.

Mascotherapy teaches you to hear inner voices, to enter into dialogue with them, to find your center and to reassemble the self anew. Over decades of practice, I have expanded this method by including work with altered states of consciousness, dialogue with subpersonalities, and the exploration of time, archetypes, and symbolic forms.

This is not a universal tool, but it is rare and precise. The method is as unique as a sculptural self-portrait in the history of art — and just as powerful: it restores a person’s sense of self, their inner grounding, and their face in an age of mass depersonalization.

If you wish not just to “get to know yourself,” but to truly encounter your authentic Self — this book is for you.

Foreword

Mascotherapy stands as one of the rare psychotherapeutic approaches that unites artistic creation, Jungian depth psychology, and a decades-long clinical practice into a coherent and transformative method. Its originality lies not only in the combination of sculpture and therapy but in its ability to use the act of sculptural self-portraiture as a structured journey into the archetypal layers of the psyche.

This method, developed and refined by Sergey A. Kravchenko over many years, extends the pioneering work of Dr. Gagik Nazloyan while opening new dimensions: the integration of altered states of consciousness (ASC), the exploration of subpersonalities revealed through portrait work, and the creation of internal dialogues that reach beyond conventional psychotherapy. Kravchenko’s experience spans decades of clinical practice, hundreds of therapeutic portraits, and a community of students not only in Russia but also in other countries — evidence that Mascotherapy has grown into an international discipline.

In “Sculptural Portraiture as a Path to Self-Understanding and Personality Transformation,” this book references global research and connects the method to contemporary neuropsychology and art therapy. Yet its roots reach deeper — into the traditions of analytical psychology, where C. G. Jung described the face as a mirror of the Self and emphasized the necessity of engaging with archetypes rather than suppressing them.

Mascotherapy is as unique as the sculptural self-portrait itself — a genre virtually absent in the history of world art. While ancient civilizations left us masterpieces of portrait sculpture, they were always created by others, never by the subjects themselves. Mascotherapy changes this: the person becomes both sculptor and model, simultaneously creator and created. In doing so, the method bridges millennia, connecting today’s search for identity with the timeless human impulse to give form to the soul.

In a century often marked by anonymity, digital masks, and the erosion of personal presence, Mascotherapy is not for everyone. It is a method for those who consciously seek their own face — inner and outer — in an age of depersonalization. It demands honesty, perseverance, and the courage to meet what lies beneath the masks. Yet for those who take this path, the reward is profound: the rediscovery of individuality, the integration of fragmented inner parts, and a restored dialogue between body, psyche, and spirit.

About the Book

The human face is a unique psychosomatic structure — a dynamic mirror of personality, reflecting the deep processes of the soul and its unconscious archetypes. If the soul has a form, it is arguably most akin to the human face, concealed beneath numerous psychological masks. Contemporary psychotherapy increasingly faces the challenge not only of recognizing these masks, but of developing harmonious relationships with them — in the service of personal integrity and the restoration of internal dialogue.

This work is the result of more than twenty years of applied practice in Mascotherapy — an authorial adaptation of the method originally developed by Dr. Gagik Nazloyan. Over this time, a substantial body of clinical and consultative experience has been accumulated, which is here presented in a structured and accessible format. The method has been applied across diverse psychotherapeutic settings — from individual consultations to group therapy in clinics addressing addiction, psychosomatic conditions, and disorders of identity.

The earliest notes date back to 1998, during my initial training with the method’s founder. More than two decades have passed since then. Although Dr. Nazloyan is no longer with us, his school continues to evolve. New practitioners have emerged, core concepts have been refined, and the theoretical foundations have expanded. These developments necessitate further systematization and scholarly reflection.

This book is a revised and abridged edition of Mascotherapy-1: How a Portrait Reveals, Develops, and Heals the Personality (2019). It is intended for professionals in the fields of psychology, psychotherapy, and art therapy, as well as educators and researchers in related humanistic disciplines.

Mascotherapy occupies a unique place at the intersection of psychology, art, and the phenomenology of the self. Its central aim is the restoration of a coherent self-image through visual expression and the externalization of the personality’s internal structure.

September 2019

Sergey A. Kravchenko

Psychotherapist, researcher, author of the method “The Face of the Personality”

Dear Reader

For a third of my life, I have practiced Mascotherapy. I first encountered the method of Dr. Gagik Nazloyan in the early 1990s. Since then, regardless of the client who sits before me — no matter how wounded, no matter how lost — I no longer feel the uncertainty that often visited me in the early days of my practice, when a suffering soul would enter the room.

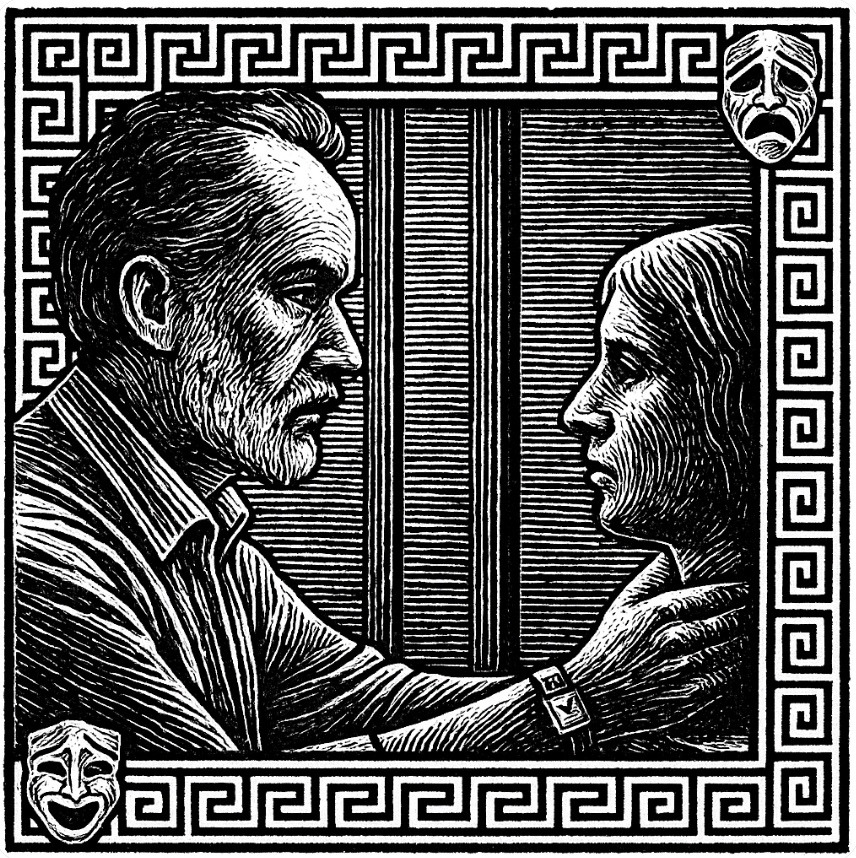

I take a piece of clay, or simply a pencil and paper, and invite my client to create a portrait or self-portrait. This act alone establishes a unique therapeutic space — disarming, grounding, and deeply symbolic. In creating a person’s portrait, we place their face — and the complex, masked personality behind it — at the center of the therapeutic universe. Without this visual anchor, a conversation can drift away from the essence of the individual, losing its depth and focus.

Around the portrait, something singular emerges — an atmosphere of trust, intimacy, even reverence. It is as if we are sitting in sacred conversation, not only with the person before us, but with the soul behind the face.

A Story from the Founder

Dr. Nazloyan once shared a powerful story. As a psychiatrist, he entered a hospital room where the patient was hiding under a blanket — a common defense he had used for years to avoid any therapeutic contact. Dialogue had proven impossible.

Without asking the patient to emerge, Dr. Nazloyan sat down and began sculpting what he imagined the patient’s face might look like. He worked in silence, occasionally commenting aloud, wondering what this hidden face might express. Within ten minutes, the patient began peeking from under the blanket. After thirty minutes, he was sitting on the edge of the bed, his feet dangling, engaged in warm conversation about the portrait’s likeness and meaning.

A portrait in the therapist’s hands can do what words cannot.

The Power of the Portrait

This story reveals something essential: even for those who have lost all interest in life and others, a portrait can awaken curiosity — especially toward the one person they still secretly wish to know: themselves. A self-portrait becomes a key, a mirror-twin that invites dialogue.

When we gaze upon a face sculpted or painted centuries ago, we are transported. Time collapses, and the past becomes present. This leads to a profound insight: only the portrait can overcome time. It suspends the temporal flow, rendering the soul behind the image timeless and eternal.

So too, when we create a portrait today — it may live a year, ten years, or a thousand. In sculpting the image of a client, we suspend time and give shape to something eternal within them. Even if we avoid explicitly philosophical language, the client may still experience a glimpse of timelessness, a fleeting encounter with the immortal soul reflected in clay.

On Becoming a Mascotherapist

My students often ask: Can I practice Mascotherapy if I am not an artist?

Let me be clear: if you believe you cannot draw or sculpt, then you will not. But if you allow yourself to remember — as children remember — that you can shape and create, then you will become an artist. The moment faith in this capacity awakens, you will begin to see your own hands as capable.

Children who enter my studio never doubt their creativity. They grab the clay without hesitation and simply begin. You must do the same. Once belief is born, you are already a sculptor. And I will teach you how to use these tools in a therapeutic setting.

Doubt in your artistic ability will limit your therapeutic depth. But once the artist in you awakens, you will discover that you possess all you need to begin. In my practice, hundreds of people who claimed they “couldn’t draw” have created striking self-portraits within weeks.

How to Begin

Take a piece of clay or plasticine. Sit before a mirror. Observe your face — and begin. Do not listen to voices that tell you you’re not an artist. The depth of your soul will guide your hand. Your quiet, true self will show you how to sculpt your double.

Each day, as your image takes shape, you will begin to see more than you ever expected. Keep a diary. Photograph the portrait as it evolves. Track your inner experience.

Pay attention to the associations that arise as you sculpt — they are often clues from subpersonalities or masks you carry. These impressions will show you what within your psyche longs to be seen, understood, and integrated.

Your work will be even more powerful if you journal your thoughts, emotions, and visions in tandem with sculpting. Even when these seem unrelated to the portrait — trust them. With the portrait as your anchor, nothing is accidental. Everything around it is a manifestation of your evolving self.

Time and Dialogue

It is difficult to say whether a portrait influences life, or life influences the portrait. Most likely, they are interwoven in a synchronous dance.

Here we arrive at a key concept: dialogue. Dr. Nazloyan placed dialogue at the center of Mascotherapy, observing that the absence of inner dialogue often characterizes psychological suffering. Without inner dialogue, there is no true outer dialogue.

But when we engage in this reflective process — sculpting, journaling, conversing — we revitalize inner dialogue. And as it grows richer, so too does our outer communication, our life, our relationships. As we master these inner conversations, we begin to influence the world around us with greater clarity and intention.

Thus, it is not only the portrait, but the dialogue it evokes, that becomes central to the transformative power of Mascotherapy.

A Final Word

Dear reader, allow me to caution you: do not approach this method mechanically. A portrait alone may not perform miracles — though sometimes it does. It is a tool, a powerful one, that in the hands of a skilled and sincere practitioner can transform both the soul and the surrounding world.

A portrait often outlives its subject. It defies time and immortalizes the soul. In this, portraiture transcends art therapy and touches the threshold of the eternal.

A wise man once said: “Every act of the artist echoes in eternity.”

I would add: “Every portrait reflects the mirror of the eternal soul.”

Create portraits. Shape your soul and the world around you.

Perhaps this is the higher meaning of life — and of our dialogue with ourselves, others, and the mystery that connects us all.

S. A. Kravchenko

Author

2019

INTRODUCTION

The introduction to this book on mascotherapy outlines the core theoretical and philosophical foundations of a method that fuses artistic approaches with depth psychology. The author presents mascotherapy not merely as a variation of art therapy, but as an independent psychotherapeutic practice, capable of revealing and transforming the unconscious dimensions of the personality.

Particular emphasis is placed on the role of the self-portrait as an instrument of self-discovery and spiritual transformation. By drawing a parallel with the biblical act of creation, the theme of the image’s autonomy and the unpredictability of the creative process is introduced, highlighting the phenomenological depth of the method. The text weaves together personal experience, scientific reflection, and cultural archetypes, establishing a compelling framework for understanding mascotherapy as a dialogue with the face, the self, and time itself.

Mascotherapy, in my practice, is an adapted method of G. M. Nazloyan, applied in diagnostics, counseling, and psychotherapy with both individuals and groups. Although traditionally classified within art therapy, in essence, mascotherapy transcends the boundaries of conventional art-therapeutic approaches, surpassing them in depth and effectiveness.

For millennia, human culture has accumulated knowledge of the personality through the portrait. Artists have always recognized the extraordinary power of the portrait to reveal, emphasize, and even shape a person’s unique traits. Today, this archetypal approach is returning — but within the framework of contemporary psychological practice.

The mascotherapeutic method is both intuitively accessible and deeply natural. It draws upon cultural codes and the inner mechanisms of personal development rooted in human evolution. It unites art and science, archetype and diagnosis, image and transformation.

The self-portrait in mascotherapy becomes, in essence, a scientific method realized through the medium of art. Within it, both conscious and unconscious attitudes of the creator are spontaneously expressed: their relation to people, gender, family, ethnic and ancestral identity, and to themselves. What was previously hidden becomes evident — not only to the person themselves but also to a mindful observer. This broadens our understanding of personality, values, and inner structure.

The visual language of the portrait is not merely a means of expression, but a tool of transformation. It can illuminate deep layers of the soul and initiate processes of inner renewal. Creating a self-portrait is always an experiment — an act of identification, discovery, development, and affirmation of the self. Yet this process resists total control: the creator can never fully predict the result.

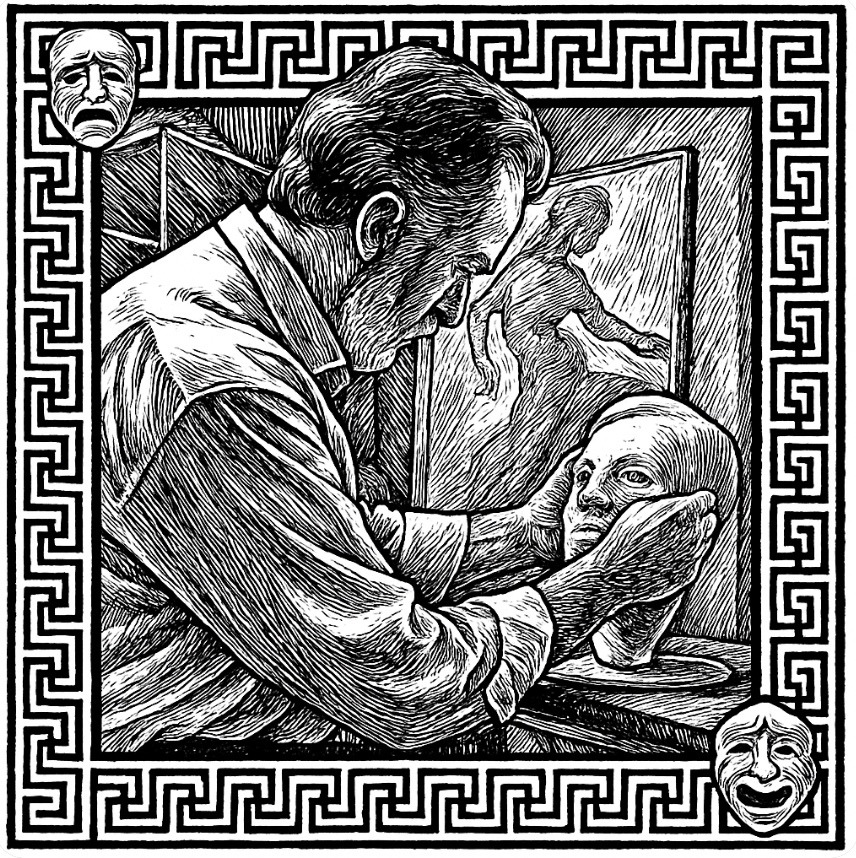

A plaster portrait in the process of casting

In this act of creation, an ancient biblical motif arises involuntarily: “And God formed man from the dust of the earth in His own image and likeness.” But did He know where His creation would lead? One can only speculate. One thing is certain: from the beginning, there was an open uncertainty. God created — and watched what would come of it.

The created image, having gained a will of its own, stepped beyond the Creator’s design, broke the established order, and deviated from predictability. Is this not precisely what happens in the process of sculpting a self-portrait?

A person forms their image, sensing that at some point it might acquire independence. Deep inside, they feel: the face they are shaping will not fully obey them. It will assert its will and begin to live its own life.

The first revelation on this path is the collapse of the illusion of control. The self-portrait escapes its maker’s grasp. It becomes autonomous and begins to affect its creator. This phenomenon may well be seen as a universal law of the creative process: the result always transcends or diverges from the original intent, becoming an entity in its own right.

Of course, the portrait is also a work of art. And if it is imbued with inner depth, it can captivate the viewer, evoke a response, and generate new meanings. One seems to hear a voice from within: it evokes wholeness, stirs associations, and connects threads of personal and cultural memory. In such cases, a face once molded begins to live — giving birth to a new life within us.

Why Mascotherapy?

In this chapter, the author reflects on the very name of the method, introducing the reader to the symbolism of the “mask” as a key concept in both psychotherapeutic and philosophical contexts. The mask appears not only as a metaphor for protection or concealment but as a phenomenon that structures personality, shapes the dialogue of subpersonalities, and defines psychological dynamics. Through personal observations, patient dialogues, and cultural parallels, the chapter explores the paradoxical nature of the “true face” — a rare, shifting, and flickering essence that reveals itself only within the space of inner dialogue and creative expression. The author comes to a conclusion: if we work with masks, there is no other name for this method than mascotherapy.

I am often asked: why is the method called mascotherapy?

This question contains many layers of meaning. One of them once led me, in another book, to propose an alternative name — The Face of the Personality. That was already a step forward, a development of the core idea. However, over the past decades, the term mascotherapy has taken root — both among professionals and clients. And this is no coincidence.

The word mascotherapy is simple, resonant, easy to remember. It may not immediately reveal the essence of the method, but it lives its own life. Just like a mask — something a person may wear all their life, hiding their true face, or never even knowing what it truly is.

Yet once we look deeper into the method, it becomes clear: no other name is possible.

In the process of creating a portrait or self-portrait — the primary tool of mascotherapy — physical resemblance is often absent in the early stages. Instead, seemingly random images emerge. But in fact, they are deeply regular. Why? Because with repeated attempts — especially in larger scale — these images return again and again. Moreover, they always resemble someone who once had a strong influence on the formation of the person being portrayed.

And what is most striking: such influential figures appear not only during portraiture but also during self-portraiture. One begins to realize that these images are inseparable from the person’s face, bound to it as subpersonalities are bound to the personality itself. These images can rightly be called masks — companions of the Face.

There are usually several such masks. Each of us has our own, and we could even name them. In the process of portrait creation, faces arise from the depths of memory — like from a fog — the faces of those once imprinted in the soul and now part of its structure. Outwardly, these traces appear as biological masks, obscuring the authentic face. Sometimes the mask is more visible than the person themselves. Hairstyle, gestures, mannerisms, intonations — and suddenly, we are no longer seeing them, but a double of an idol: a singer, politician, or ideologue.

Why Mascotherapy? (Continued)

Among world-class scholars, it is not uncommon to encounter the view that there is no such thing as a “true self.” One of my patients, a deeply reflective individual, once asked:

“What if there’s only emptiness behind all the masks? What if the true face you are trying to find in each of us simply doesn’t exist?”

Surprisingly, both of these seemingly opposite views hold truth in their own way.

The first — the one I personally hold — maintains: the true face does exist; it can be discovered or created.

The second suggests: there is no true face — only a succession of masks.

But how can both be true at once?

The resolution of this paradox came to me not so long ago. Its essence is this: the true face is an indeterminate, flickering essence — akin to quantum light. It can be found only within the “cloud of masks” a person assumes throughout life, often unconsciously. The true face may even transcend these masks — but only when the soul rises to its highest state. That is the state of the Creator — the condition of an authentically creative self.

Not one who imitates or consumes.

For in imitation of an idol, a person loses their own face.

And in living solely to satisfy needs, one forgets their very nature.

Masks conceal the true self, substitute for it, prevent its emergence, or keep it from being recognized. And even when it does reveal itself, there is no guarantee it will persist or be perceptible. The weaker the personality, the more likely it is to lose its face in the presence of others, slipping into the mask of a social role.

A special significance lies in the interplay of faces within the therapeutic space. In a face-to-face session, the client and therapist inevitably exchange masks — doppelgängers. The client may carry away the therapist’s mask — it may support them for a while. The therapist, in turn, receives the client’s mask — and must know how to release it. Otherwise, it begins to affect their own life.

Mascotherapy takes a different path. Here, the client sits before a mirror, contemplates their face, and creates their own portrait. The therapist recedes into the background. This subtle distinction is of fundamental importance.

So why, after all, do we call it mascotherapy?

Because, in essence, we are never working with the face itself — but with masks. The true face is rare. It is like a precious stone: it appears unexpectedly and only under special conditions. Masks, however, are everywhere. Society encourages them, distributes them, adapts them. And from birth, human beings are designed to accept and use masks effectively.

Mascotherapy helps us explore these masks and the subpersonalities behind them. It allows us to build inner dialogues — consciously or not — between the masks we wear. Ideally, the individual learns to speak with them openly, to understand them, to integrate them into their sense of self.

In the most severe cases — as G. M. Nazloyan wrote — the patient’s inner dialogue may be completely absent at first. This is the core of their suffering: pathological aloneness. But when the first response appears — in a portrait, in a mirror, in another’s gaze — then the internal dialogue begins to stir. And from within the subpersonalities, the first inner conversation begins to take shape.

The concept of the mask in mascotherapy is not an abstract metaphor. It is a concrete, observable reality. The masks in portraits are not always benevolent. Sometimes they evoke heavy emotions. But once they appear, they become objects of external observation. And thus — they can be engaged with, spoken to, and transformed.

If a method works with masks — how else could it be named?

The Essence of Contemporary Mascotherapy

This chapter forms the methodological core of the book. The author articulates mascotherapy as a unique integrative method that combines the artistic practice of portrait creation with deep psychological work involving the multilayered structure of the personality. Through the process of creating self-portraits, different strata of the psyche are revealed — from instinctual and ancestral layers to personal and leadership levels. Mascotherapy is presented not merely as a therapeutic modality but as a path to inner transformation, self-knowledge, and even a touch of eternity. Special emphasis is placed on the aesthetic mediator — the portrait — as both a tool of transformation and a vessel of the immortal image. This chapter outlines the boundaries between mascotherapy and other methods, arguing convincingly for its uniqueness.

Mascotherapy is a developmental, diagnostic, psychotherapeutic, and consultative practice in which the central element is the creation of a sculptural or graphic portrait. Additional forms may include theatrical makeup, photographic portraiture, or video recordings of the client’s dialogue with the therapist — and with their own portrait.

The method facilitates the unveiling of a person’s true self-image, helping to uncover, complement, and evolve layers of personality previously hidden from awareness or distorted. These layers include:

— the instinctual foundation with its drives and needs,

— the anthropic (universal human) layer and connection to nature,

— the ethno-genealogical stratum and ancestral memory,

— the social (familial) level,

— individual traits,

— the personal level,

— the leadership potential.

Focusing on each of these levels through portrait work helps to unlock psychological energies that were previously repressed or inaccessible. This leads to an increase in psychic energy, the awakening of hidden capacities, improved adaptability, harmonization of inner life, and, in many cases, the alleviation of psychological distress.

The Initial Stages of Portrait Work

Mascotherapy sessions vary in nature, duration, and frequency. They can last from a few minutes to several hours. The portrait or self-portrait development process often proceeds alongside diagnostic or therapeutic conversations, but long periods of silent client work are also possible. A portrait may evolve over several sessions — or span months or even years.

The number of sessions ranges from 5–10 to 20 or more, depending on the client’s task and internal resources. In most cases, it is the client who determines their readiness to meet the portrait — and thus themselves.

Mascotherapy is rooted in the tradition of portrait art — sculptural, painterly, and graphic. From the earliest times, artists have recognized the power of the portrait: it gave the image durability, outlived its creator, and preserved memory. The aura of immortality has always surrounded portraiture, making it a natural mediator in the processes of psychological guidance and healing.

The essence and power of the method lie in the portrait’s ability to lead the client into inner states where the experience of eternity becomes accessible — a transformative encounter that changes the personality. This kind of experience allows the individual to connect with the dimensions of time — past, present, and future — overcoming timelessness, inner void, depression, and identity crises.

More on this topic can be found in S. A. Kravchenko’s book “Temporal Psychology”, which explores the relationship between psychological processes and temporal dimensions.

More Than Psychotherapy

It is important to understand that mascotherapy is not always psychotherapy in the narrow sense. It can also serve as a developmental or corrective methodology, acting as a central axis around which other approaches in psychology, education, or therapy may revolve. It can be used for:

— self-exploration,

— diagnosis,

— personal development and correction,

— revealing abilities and talents,

— life-path discovery,

— finding one’s unique Face.

The method is particularly indicated in cases where body-image connection is impaired, identity perception is distorted, or contact with reality is diminished. Mascotherapy makes it possible to reach the individual level (the fifth layer) and, at times, go beyond it.

For deeper work, the method “The Face of the Personality” is used — a development that has grown out of mascotherapy. It allows the exploration of personal and leadership levels of the psyche — including their potential pathologies. This will be explored in detail in the forthcoming book “The Face of the Personality.”

From Drama to Dialogue

It is within the sculptural portrait that the “inner dramas” of the masks are most vividly enacted. Here, conflicts are revealed, and dialogues between subpersonalities emerge. This becomes a path toward inner harmony and the affirmation of the Self.

Simply removing a papier-mâché mask is not enough. Humans possess more masks than social roles, and most of these are internal. More on this topic can be found in the book “Masks, Faces, Images,” which explores the functions and typology of masks.

On going beyond masks and roles, see the book “Notes of a Hermit,” where the path to the liberated state of the pure Self is revealed.

The Innate Ability to Sculpt

This chapter reveals a key principle of the method: every person is a creator. Even those who consider themselves “not artists” possess an innate ability to sculpt, along with a natural drive for self-expression. Here, mascotherapy transcends aesthetics and becomes a means of overcoming internal barriers — shame, fear of failure, and creative paralysis. The collaborative process with the therapist, the “exchange of portraits,” symbolizes an act of co-creation and support through which a person can restore lost contact with themselves and their creative origins.

Almost every first encounter with sculptural mascotherapy begins with the same question:

“What if I don’t know how to sculpt?”

Interestingly, such questions are most often asked by adults. Children, by contrast, take clay in hand without hesitation and immediately begin to create. And — it works. It turns out that everyone can sculpt. Even those who haven’t touched clay in decades. The difference lies not in ability, but in one’s attitude toward the process.

Pragmatic, goal-oriented individuals with no artistic background often manage the task more quickly than others. Their self-portrait may be far from technically refined, yet it contains honesty, raw strength, and a unique, recognizable face. Such portraits often make a strong impression — precisely because of their sincerity and vivid presence.

Things are different with clients who approach the task with hesitation. For them, clay seems threatening: they fear ruining it, doing something “wrong,” receiving poor judgment. Old school-era fears are carried into the creative space — and instead of a living expression of the soul, anxiety emerges.

In such cases, synchronized sculpting proves helpful. If the mascotherapist works alongside the client, sculpting an identical portrait, they can offer their version at the right moment — suggesting more accurate form or direction. After a while, the therapist takes the figure back and refines it. As a result, both work with two sculptures, passing them back and forth. A process of co-creation emerges — where it no longer matters who made what, but rather that together, something greater is achieved.

To avoid confusion, it helps to use different colors of clay: for instance, the main portrait in a flesh tone, and the auxiliary one in olive or dark hues.

Thus, step by step, the client gradually and unconsciously enters the state of a creator. Their hands begin to remember. Their soul — awakens. And, as practice shows, by the end of the session, the person not only has their first self-portrait, but also their first victory over self-doubt.

Methodology within Clinical Practice

This chapter presents mascotherapy as a clinical method centered not on the symptom, but on the person — one experiencing internal conflict, a loss of self-identity, and existential loneliness. In working with portraiture, the individual not only “recreates” their face but also re-establishes contact with the body, ancestral memory, gender, and personal identity. The stages of therapeutic portrait-making are described as a form of deep initiation. The method lies at the intersection of Jungian analytical psychology, temporal psychology, and symbolic art.

What distinguishes mascotherapy as a complex of psychotherapeutic and developmental techniques is its fundamental view of the client — not as a bearer of symptoms, but as a whole personality who has temporarily lost connection with themselves and the world. The focus lies on internal conflicts, distortions of self-identification, and the phenomenon of pathological loneliness, which, according to G. M. Nazloyan, is a universal symptom of most mental disorders.

Modern culture increasingly contributes to depersonalization, the loss of subjectivity, and the substitution of the “Self” with roles, masks, and clichés. This leads to a breakdown of inner dialogue and a rise in psycho-emotional and existential problems. The phenomenon of “losing one’s face” becomes not just a metaphor, but a central element in the disruption of self-perception and the distortion of relationships — with oneself, with others, and with reality as a whole.

Mascotherapy enables one to “restore the face” — that is, to reestablish coherence between the bodily image and personal consciousness. It is a path to reconstructing the lost “Self,” a method of reviving dialogue — first internal, then external. The therapeutic effect is achieved through symbolic self-creation. A sculptural portrait plays a crucial role here: unlike painted or drawn portraits, it has volume and corporeality, which facilitates identification with the image and deepens the therapeutic process.

One of the method’s unique features is the presence of three participants in the therapeutic process: the client, the psychotherapist, and the portrait. This triad creates a distinct therapeutic space, where the therapist’s role is not to impose interpretations, but to gently accompany and guide the process of self-discovery.

S. A. Kravchenko, a student and follower of G. M. Nazloyan, adapted and expanded the method by integrating it with Carl Jung’s analytical psychology and the theory of temporal psychology. The therapeutic work follows sequential stages corresponding to “layers of the psyche,” each associated with a specific level of personal development and self-understanding:

Stages of Therapeutic Portraiture

— Animal Level — the shape of an egg. Reflects perinatal and postnatal experiences, birth trauma. Often, the client cannot even sculpt this basic form.

— Task: Restoring basic trust in the world.

— Anthropic Level — coarse features resembling archaic sculpture.

— Task: Awareness of one’s relationship to the human community.

— Ancestral Level — a face showing signs of gender and family lineage. Difficulty in defining gender often emerges here, signaling psychosexual disturbances.

— Task: Restoring gender, familial, and ancestral identity.

— Family Level — facial traits begin to reflect those of relatives (grandparents, etc.).

— Task: Working with ancestral memory; overcoming unconscious identification with traumatic family fates.

— Individual Level — emergence of a distinct, recognizable face.

— Task: Forming an integrated “Self” and its temporal coherence (past, present, future, timelessness, eternity). This is the level of catharsis, meaning-making, and the overcoming of temporal neurosis.

— Personal Level (optional) — the stage of self-determination and depth.

— Task: Developing worldview and a mature personality.

— Leadership Level (optional) — awareness of one’s unique mission and responsibility to the world.

— Task: Awakening of spiritual leadership.

The process begins with something small — a sculpture in the shape of an egg.

With each stage, new layers are added, yet the previous ones are not destroyed — they remain within, as symbols of memory and experience. Ideally, the final form approaches the actual size of the patient’s face.

During the creation of the portrait, symbolic and associative processes are activated. For example, a woman may see in the portrait features of her father or a beloved man. In another case, a patient realizes that he is living out someone else’s life script — his grandfather, who struggled with alcoholism, unconsciously became a behavioral model. This insight gives rise to an inner cleansing and a search for one’s own path.

As the resemblance increases, a sense of a “double” emerges. An emotional connection is established with the image, and an inner dialogue comes to life. This leads to catharsis — emotional release and a deepened understanding of oneself and one’s issues.

The psychotherapist’s task is to create the conditions in which the patient can become emotionally attached to their own face. This is a sign that therapy has reached its conclusion. In some cases, the patient is invited to leave their portrait at the clinic — as a symbolic act of parting with illness. Later, the practice of returning the portrait to the client was introduced, allowing them to continue the work at home or remotely.

Mascotherapeutic Techniques Include:

— Verbal portrait;

— Face painting (make-up);

— Photographic portrait;

— Graphic or painted portrait;

— Sculpture from a live model (sculptural portrait).

The method is used in clinical institutions (such as Rehab Family) for the treatment of depression, neuroses, and addictions. Noticeable improvements in emotional well-being and a reduced need for medication are often observed after just 3–4 sessions.

Group formats significantly enhance the therapeutic effect. Clients help each other in the creation of portraits, share observations, and strengthen the process of objectification and acceptance. Family members can participate in the process — comparing likenesses, affirming the importance of what is happening. All of this helps the patient to “regain their face” — not metaphorically, but quite literally.

Thus, mascotherapy becomes not only a method of diagnosis and correction, but a profound process of initiation. To regain one’s face is to return to oneself, to one’s true nature, and to the capacity to live not by someone else’s example, but as a person capable of being truly oneself.

Field of Meaning

This chapter explores the philosophy of the face as a mirror of the soul and the central image in mascotherapy. The mirrored double, the portrait, and the inner dialogue form a field of self-knowledge. The chapter discusses archetypes, masks, layers of the psyche, and the theme of identity. The author touches on the phenomena of catharsis, eternity, the image of the therapist, and the role of perfection. It concludes with a reflection on the connection between a person’s inner and outer appearance, revealed through portrait work.

Face and Mirror

At the core of mascotherapy’s conceptual field lies the face. Through its reflection in the mirror, a person enters into contact with the image of the self. The personality and the soul partially manifest in the face’s expression in the here and now. In observing our mirrored double, we are, to some extent, observing ourselves.

Dialogue with the Double

The dialogue that arises between the personality and its mirrored reflection may become an even more accurate tool for reflecting the soul. Thus, the central element of mascotherapy becomes the face reflected in the mirror — the one hiding the personality — and the dialogue with it. But how accurately do we perceive our own reflection? That cannot be fully known until we attempt to create a portrait.

The Portrait and Observers

By creating a self-portrait while observing their own face in a mirror, a person has the chance to show others what they themselves see. This raises a vital question: how accurately do we convey in a portrait what we perceive? The interaction of observers around the portrait forms the initial dialogue — the criterion of image authenticity.

Masks

In the first stages, masks emerge — stable social roles and archetypes that have surrounded us since childhood. These masks are not accidental; they are part of our psychic and social nature. We should not fear them, but it is crucial to be aware of their presence.

The True Double

The mirrored double is an illusion — but a necessary one. It allows us to see ourselves from the outside, though it reverses left and right. After a few weeks of sculpting, if the work progresses properly, the portrait ceases to be a mirror image — the brain replaces the distorted reflection with an internally recognized form. This marks the shift from external observation to internal vision.

Self-Image

What often prevents the creation of a true portrait is the entrenched image of oneself — a construct made from others’ opinions, past experiences, and social roles. This internal image must be overcome in the search for the authentic face. Masks and self-image intersect, but they are not the same. A mask exists in relation to others, whereas self-image persists even in solitude.

Layers of the Psyche

The true face does not emerge immediately — it lies hidden beneath seven layers of the psyche:

— The animal level (egg-like form),

— The universal human level (emergence of a human image),

— The ancestral level (gender, ethnicity),

— The family level (features of close relatives),

— The individual level (distinct personal traits),

— The personal level (existential meaning),

— The leadership level (the image of a guide who transcends time).

Cloning Faces

While sculpting a patient’s portrait, a therapist may unintentionally imprint their own features onto the image. This is a subtle but important point. To avoid such “cloning,” it is essential to leave the patient alone with the image. Only in solitude can the true face emerge.

Eros and Thanatos

The archetype of Eros — creation — is active during sculpting, but Thanatos — death — is never far. Sculpture is associated with memory, the overcoming of time, and a quest for immortality. A timeless portrait becomes a symbol of the soul’s eternity.

On Eternity and Timelessness

Patients often perceive their portrait as a future or improved version of the self. The portrait captures not only the past, but also the future — it opens temporal dimensions. In the state of timelessness experienced by many patients, creating a portrait becomes an act of creation and a means of returning to the flow of time.

Catharsis

At the conclusion of portrait work, an emotional explosion — a catharsis — occurs. A new face emerges, triggering a cleansing of the soul in the Aristotelian sense. This experience cannot be ignored: the birth of a new self never goes unnoticed.

Status

Sculpted portraits have traditionally been associated with high social status. Because of this, some patients may initially feel unworthy. However, the very process of creating a portrait helps to overcome this belief and affirm one’s self-worth.

Perfection

The portrait’s form must be as precise and perfect as possible. This teaches the person to strive for a kind of perfection — not narcissistic, but soulful and spiritual. A perfected portrait allows one to move beyond masks and draw closer to essence.

Associated Images

During portrait work, images of other people often emerge — significant figures, archetypes, shadows. These must be noted and reflected upon. They are active elements of the psyche and influence both the process and the patient’s life.

Inner and Outer

As the portrait develops, life itself changes. Relationships improve, attentiveness to others’ faces increases, self-understanding deepens. The portrait becomes a metaphor for the journey — from the outer to the inner, from chaos to wholeness, from image to Face.

Faces, Visages, and Images of Civilizations

This chapter reveals the archetypal and cultural-historical role of the human face as a mirror of civilizations. Through sculpted self-portraiture, a person approaches a holistic perception of themselves, their time, and their deep inner nature. Mascotherapy is presented as a means of restoring the lost dialogue between the individual and culture.

The more realistically a person is able to portray their own face, the more refined becomes their perception of the world, others, and themselves.

This idea lies at the heart of mascotherapy — the art of restoring the lost Face, both physical and spiritual. It goes beyond personal therapy and addresses a fundamental question: how capable is civilization, as a whole, of seeing itself?

Paradoxically, humanity — having created countless images of masks, idols, gods, heroes, and monsters — long avoided the most essential subject: the sculpted self-portrait. This genre only emerged with the development of mascotherapy in the 1980s. Until then, the human face in art was always interpreted by someone else: the artist, the sculptor, the state, the ideology — but never by the subject themselves.

“Know thyself” — this Delphic maxim was not truly realized in the culture of portraiture until a person took clay in their own hands and began to shape their own likeness.

Across millennia — from the Paleolithic to Postmodernism — the masks and faces of civilizations, from the simplest clay heads to monumental imperial busts, have served as mirrors of their eras.

But were they true mirrors, or distorted lenses?

In prehistoric imagery, symbolism dominated: the face appeared as a generalized sign of the clan, the spirit, or the totem.

Egyptian images were schematic, frozen in eternity.

Greek sculpture reached an apogee — portraying not a specific face, but the ideal body, praising harmony and proportion.

Rome introduced the psychological portrait to the world — a face marked by age, character, and suffering.

In Christian Europe, the visages of saints detached from the body and ascended toward the divine, gradually losing touch with individuality.

“The human face is the most meaningful of all surfaces,” wrote Georg Simmel.

But how many cultures have dared to study that surface in earnest?

Despite technical progress, modern sculpture is losing its ability to see the face. It flaunts symbolism, abstraction, and postmodern play with meaning, yet shies away from precise and sincere representations of human individuality.

One cannot help but ask:

Do contemporary sculptors — and more broadly, modern people — see their own and others’ faces clearly enough to reflect them in authentic portraits?

Do we see the world we live in — and ourselves within it — accurately and honestly?

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.