Бесплатный фрагмент - Lewwinski Business Management

Unit 1. Introduction to Business Management

1.1 What is business?

Class objectives:

— Describe the nature of business (AO1)

— Explain the economic sectors: primary, secondary, tertiary,

quaternary (AO2)

— Explain challenges and opportunities for starting up a business

(AO2)

The main point of this chapter to learn essential information. Everything you learn further is based on this chapter.

i. NATURE OF BUSINESS

Describe the nature of business (AO1)

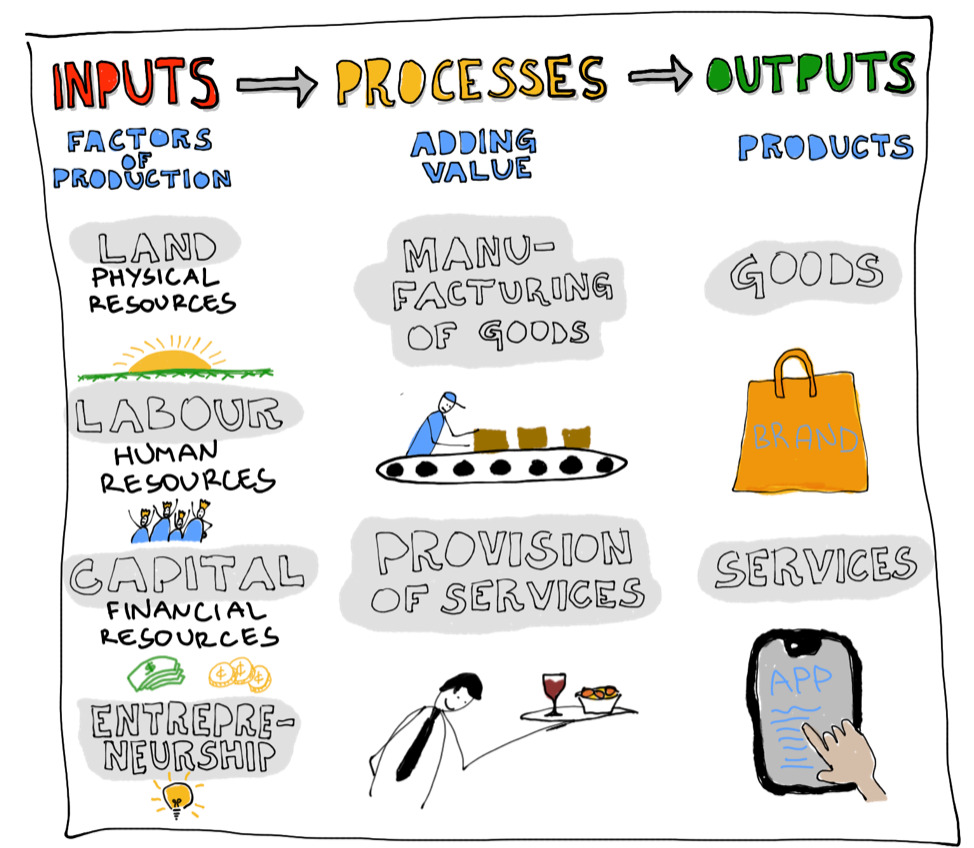

Business is an organisation that provides goods and services and satisfies needs and wants in a profitable or non-profitable way. This definition already includes some extra business terms that we’ll talk about in a moment. I believe the easiest way to understand what business is and how it functions is input-output model, that I outlined for you below.

As you can see from Figure 1 above, businesses take inputs (or resources, or factors of production — all of these refer to the same thing in our context), do certain processes with them and add value to them, and transform them into outputs. As simple as that. Now let’s talk about each of the three steps in the input-output model in more detail.

Inputs are the resources that businesses use in order to transform them into outputs by adding value. In traditional economic theory these resources/inputs are called factors of production:

— Land (physical resources) — land, real estate or raw materials, for example, fish, gold, wood.

— Labour (human resources) — people in business: employees and managers.

— Capital (financial resources) — cash and other forms of financial resources as well as capital goods, i.e. things/equipment used in production: office chairs, desks, laptops or assembly line robots.

— Entrepreneurship — skillset that combines all the factors of production in order to transform them into products (goods and services).

The second stage in input-output model is adding value. Added value is extra perks/features that are added to inputs in order to sell them to customers. If there’s no added value, there’s no business. Why would someone pay extra for something that did not undergo any transformations? The two major ways in which businesses add value are production (manufacturing) of goods and provision of services. Speaking of production, it can be either capital-intensive or labour-intensive. Capital-intensive refers to high reliance on machinery in production process. For example, car manufacturing is usually highly automated and is manly performed by robots. Labour-intensive refers to high reliance on human labour. For example, textile industry (manufacturing of clothes) is usually highly labour-intensive and depends on the manual work of people.

And finally, the last stage of the input-output model is outputs. Output is a product, that can either be tangible (good) or intangible (service). Once again, product is either a good or a service. Very often students say “product” but mean “good”. Goods are products, but not all products are goods, because services are also products. Products can also be categorised based on who they are sold to. If a product is sold by one business to another, this is a producer good or service. This relationship of one business to another is called B2B (business-to-business). For example, if a school buys desks and chairs from a furniture manufacturer, that would be a producer good. If a product is sold by business to the general public, this is a consumer good or service. This relationship is called B2C (business-to-consumer). For example, if your parents go to a shop and buy a desk and a chair for your bedroom, that would be a consumer good. As you can see, one and the same thing can be either producer or consumer good or service, depending on who it is sold to.

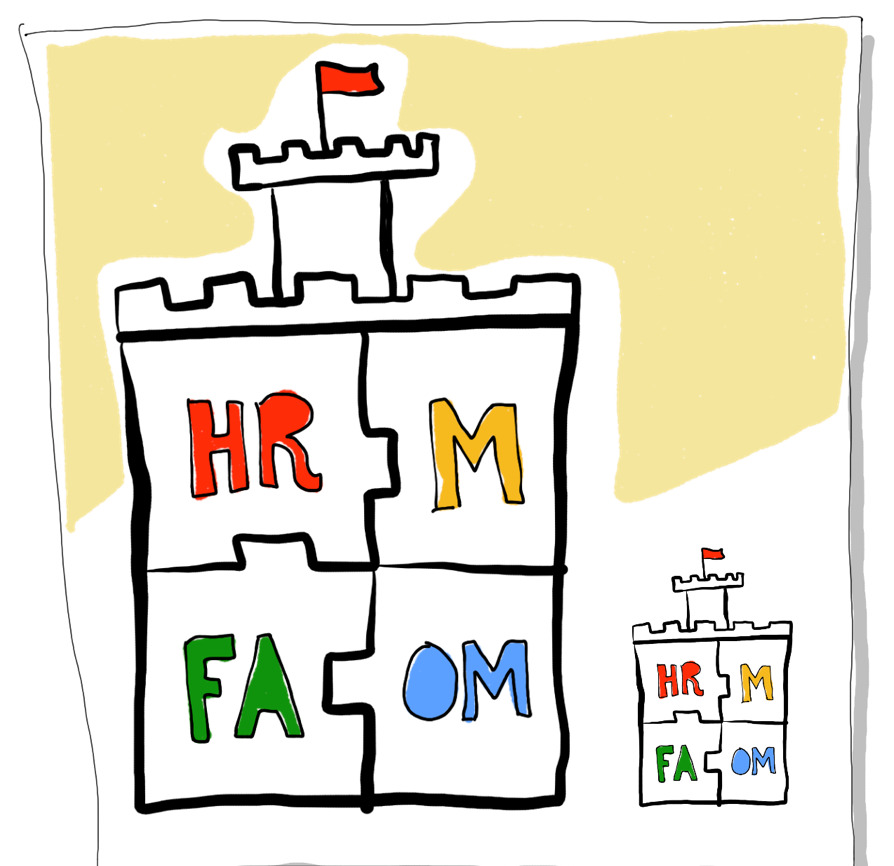

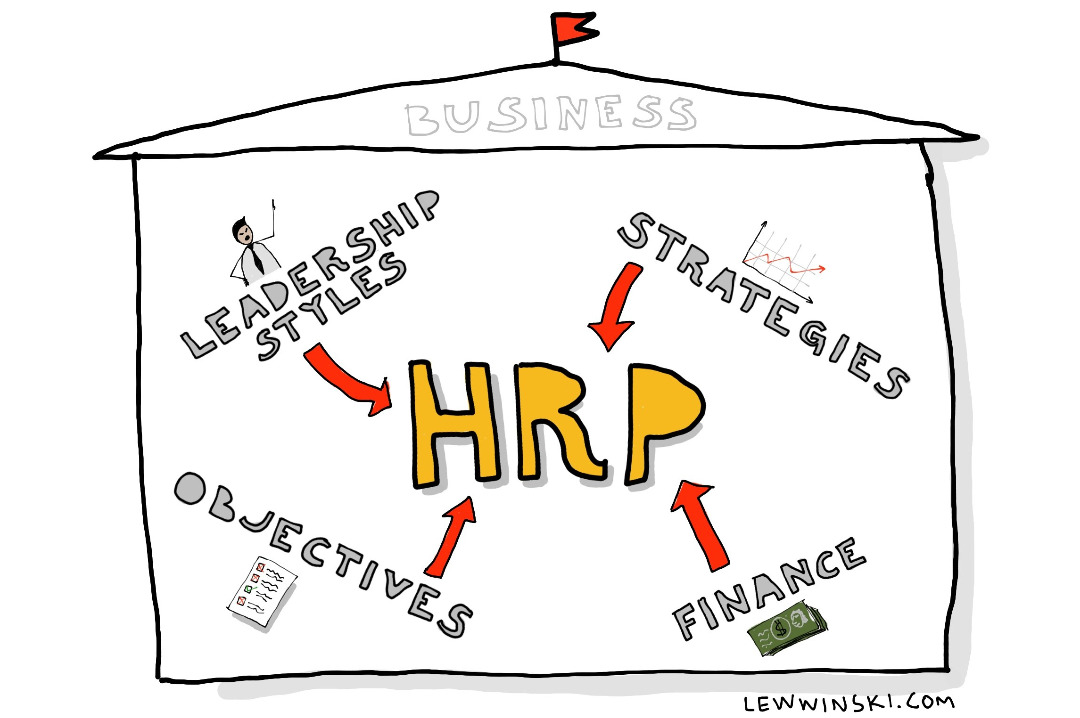

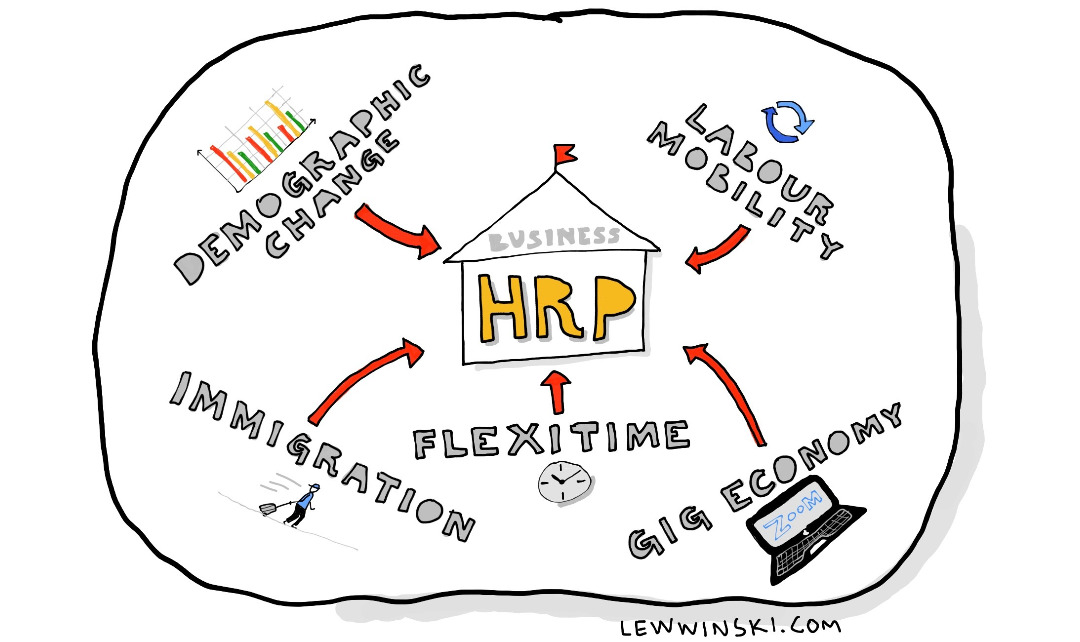

Once we are clear about what business is and how input-output model works, we’re ready to explore business further and talk about business functions. All businesses, regardless of their size, location and other characteristics have the same 4 business functions:

— Human resource management (HRM) — making sure that the right people are employed and paid by the business, regularly trained, appraised and treated in accordance with Health & Safety regulations.

— Finance and accounts — planning for the future costs, revenues and cash flow and keeping records of the costs, revenues and cash flow in the past, as well as financial analysis and budgeting.

— Marketing — making sure the right product is sold at the right price in the right place using appropriate promotion methods.

— Operations management — making sure that goods are produced using relevant methods of production and/or making sure that the most efficient processes are used to provide services.

It’s okay if you feel like you don’t fully understand what’s included in these business functions. Usually, Business Management is taught in 5 modules: introduction to BM plus 4 business functions. So, it will take about two years to figure out what these functions actually are, so take your time, and this overall understanding of the functions we have so far is enough, for starters.

Once again, all businesses, regardless of their size, have the same 4 business functions. The only difference is that, for example, a sole trader will perform all four functions on their own while in larger companies these functions will be allocated to departments. So, all businesses have 4 functions, but not all businesses have departments.

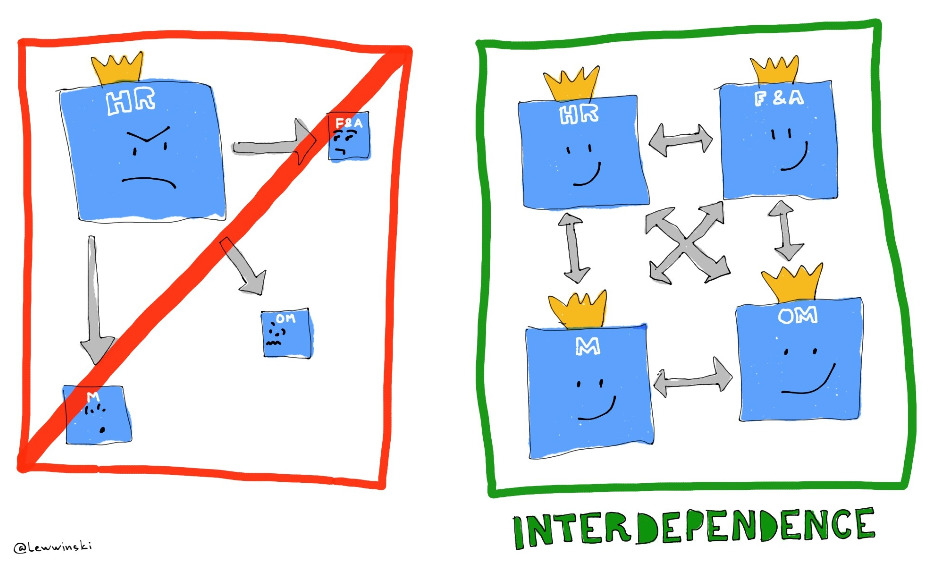

Which business function is the most important? Well, this is a tricky question. On the one hand, it is believed that HR is the one because it has to do with professional relationships. On the other hand, none of the functions should be the most important one or the least important one. Also, if an organisation is broken down into several departments, they should not be too independent from each other. It is extremely important to coordinate the actions of all functional departments and make sure all of them have a shared goal. Otherwise, the organisation will fall apart and will be in a constant state of conflict. This idea of organisation where all functions are united by common goal and rely on each other is called interdependence.

ii. ECONOMIC SECTORS

Explain the economic sectors: primary, secondary, tertiary, quaternary (AO2)

Economic sector (or sector of industry) refers to all the businesses within an economy that are involved in a similar activity. So, if you want to divide all businesses in a country into economic sectors, you have to see what they do. Overall, there are four economic sectors:

— Primary sector refers to all the businesses that extract raw materials: mining, fishing, forestry, agriculture, oil extraction, etc.

— Secondary sector businesses transform raw materials, extracted by primary sector businesses, into goods, i.e. secondary sector refers to manufacturing.

— Tertiary sector refers to provision of services: banking, education, retail stores, cinemas, transportation, etc.

— Quaternary sector is quite similar to tertiary, because it also includes services, but exclusively those services that relate to data, knowledge and IT. For example, app and video game development would be an example of quaternary sector activity. However, selling these apps and video games in retail stores would be an example of tertiary sector activity.

All the consumer goods go through economic sectors. For example, bread that you buy in a local supermarket once was crops that were harvested by farmers in the primary sector, then processed into flour by the bakery in the secondary sector, and then delivered into supermarkets (tertiary sector businesses) all over town that sell this bread to you. This route, or path, or process that raw materials go through on their way of becoming a finished consumer good is called chain of production. For some products, like bread, it is relatively short and doesn’t take much time. But for more complex goods, like airplanes, production chains are more complicated as well.

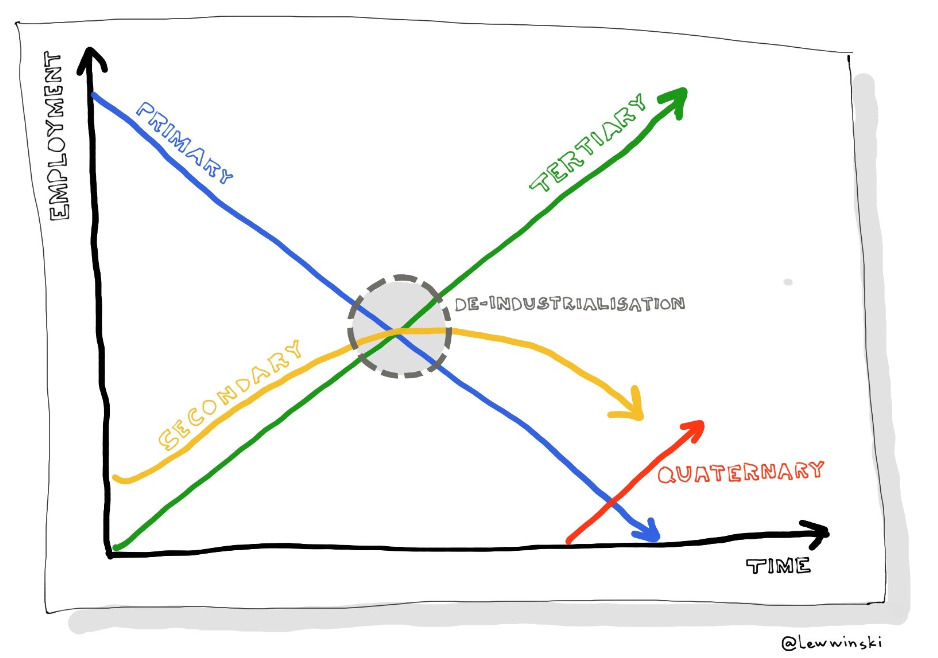

Why do we need this knowledge about economic sectors? Because you, as a Business Management student and potential entrepreneur, might make a lot of conclusions that your potential business might benefit from in the future, if you know what economic sectors are. One thing you can do is predict the future. History tells us that all economies go through the same stages of development over time. Have a look at a graph below first.

As you can see, as time goes by, the importance of primary sector declines, because there is not much added value there, that sector is simply about extraction of raw materials… Secondary sector increases first (this increase is called industrialisation) as manufacturing is growing, and then after a certain point, usually when it becomes cheaper to manufacture goods in a different country, secondary sector decreases (the decrease of the secondary sector is called deindustrialisation). Tertiary sector is gradually increasing over time, because the more economy develops, the wealthier people usually become, and the more money they prefer to spend on tertiary sector activities, i.e. services: better education, travel, opening a bank account — all of these are services. Also, as time goes by, quaternary activities are increasing because they are proportional to technological progress and development of IT.

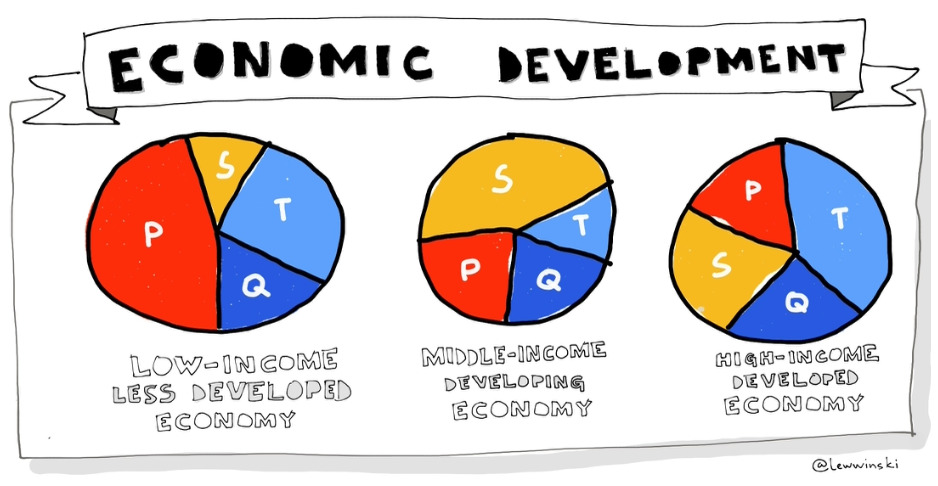

Another conclusion that you can make based on the knowledge about relative importance of economic sectors is the type of economy. Economies where primary sector dominates are called less developed economies. This usually means that workforce is not very well educated, and that quality of life and income levels are not very high. Economies where secondary sector dominates are called developing economies. An example could be BRICS: Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa. Labour costs in these countries are relatively low and these countries are a good destination to outsource manufacturing of goods. Countries where tertiary and quaternary sector dominate are referred to as developed economies. Income levels there are relatively high, and people spend money on services. At the same time, labour costs in these countries are also pretty high and it might be very expensive to manufacture goods in these economies.

One last thing about economic sectors is how to measure their importance. There are two ways:

— Count the number of people who work in this or that sector. For example, let’s say in a tiny country X there are only 100 people and 75 of them work in tertiary sector businesses: banks, schools, cinemas, barbershops. It means that the relative importance of this sector is 75%.

— Count the proportion or total value of GDP in each sector. If half of the overall GDP comes from manufacturing, then the relative importance of secondary sector is 50% and it is an indicator of a developing economy. Or, if GDP is 1 billion dollars and 600 million is generated by secondary sector, then its importance is 60%.

Keep in mind that if the sector is more important in terms of GDP, it is not necessarily the most important in terms of workforce. Very often tertiary sector generates most value, while primary sector is the most labour-intensive.

You might be interested in relative importance of economic sectors in different countries. Look up “List of countries by GDP sector composition” on Wikipedia and learn more about it.

iii. STARTUPS

Explain challenges and opportunities for starting up a business (AO2)

First, if we’re going to talk about startups (new businesses), we’ve got to talk about entrepreneurship. As you remember, it is one of the four factors of production and an essential part of any business, that refers to a skillset (or knowledge/wisdom) that allows to combine all factors of production and start an enterprise. People who have this skillset are called entrepreneurs. One of the most important characteristics of entrepreneurs is risk-taking. In addition to entrepreneurs, there are also intrapreneurs — people who are similar to entrepreneurs but who work for a company. They are usually provided with a lot of freedom, they hire people for their team themselves, they manage their time own their own and share pretty much the same opportunities and threats as entrepreneurs, but all of this is happening within a company context. Intrapreneurship is very common in Google, for example. Gmail is the product of intrapreneurship.

Having said that, we are going to talk about challenges and opportunities of startups now. The three main topics that relate to that are reasons, process (including business plan) and problems.

Reasons to start up a business. There is no one right answer to what these reasons are but some of them are really common. When I ask my students what they think the main reasons are, they usually give me very good answers! Here’s a top chart of what they usually say and a fancy BM-terminology version (in brackets) of what my students say:

1. “Getting rich!” (financial rewards)

2. “Doing something new” (innovation)

3. “Manage time on your own” (life-work balance)

4. “Find something others don’t do” (filling in the market niche/gap)

5. “No boss” (independence)

6. “I’m the boss!” (responsibility)

7. “Hobby” (commercialising personal interest)

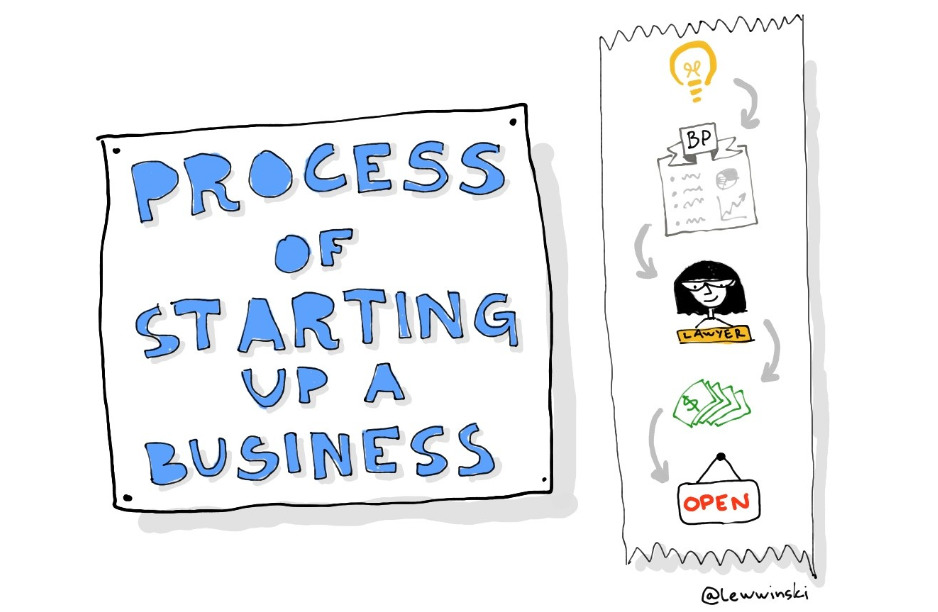

Process of starting up a business. Again, there is no one right answer, however all startups go through pretty much the same experience and follow these steps (not necessarily in this order and not necessarily these steps only):

1. Refine business idea (thinking about what the business is about in general)

2. Outline business plan (more details further)

3. Choose the type of business entity (more details in 1.2)

4. Seeking finance (more details in 3.2)

5. Start trading!

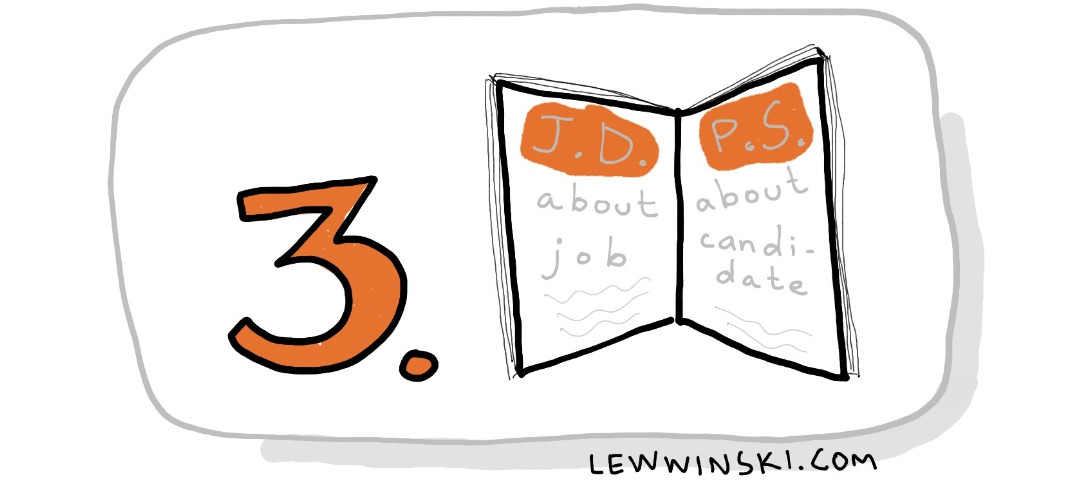

With regards to business plan, it is a document that outlines business idea and explains how business is operated functionally (in terms of 4 business functions). Nowadays, BP often includes sustainability and CSR (more about it in 1.3) — ethical standards that a business is committed to comply with. There is no one standardised format for all BPs, but a good one usually includes the elements mentioned previously in this or that way. You can play with BP and try to create your own. BP samples are easy to find online.

Problems/challenges that startups face. With regards to this topic, my students were of great help again. See below their ranking with a BM-termed explanation in brackets:

1. “No money!” (limited finance)

2. “Don’t know how to run a business” (lack of organisation skills)

3. “Nobody wants to work for me” (recruitment issues)

4. “People don’t work well” (limited expertise)

5. “A lot of other similar businesses” (competition)

Look back at class objectives. Do you feel you can do these things?

— Describe the nature of business (AO1)

— Explain the economic sectors: primary, secondary, tertiary,

quaternary (AO2)

— Explain challenges and opportunities for starting up a business

(AO2)

Make sure you can define all of these:

1. Business

2. Input-output model

3. Inputs

4. Outputs

5. Added value

6. Factors of production

7. Land (physical resources)

8. Labour (human resources)

9. Capital (financial resources)

10. Entrepreneurship

11. Capital-intensive

12. Labour-intensive

13. Product

14. Good

15. Service

16. B2B

17. B2C

18. Consumer goods and services

19. Producer goods and services

20. Business functions

21. HRM (human resource management)

22. Finance & accounts

23. Marketing

24. Operations management

25. Interdependence

26. Economic sector

27. Primary sector

28. Secondary sector

29. Tertiary sector

30. Quaternary sector

31. Chain of production

32. Industrialisation

33. Deindustrialisation

34. Less developed economies

35. Developing economies

36. Developed economies

37. Startup

38. Entrepreneur

39. Intrapreneur

40. Business plan (BP)

Check out these resources to boost your BM knowledge and skills:

— boosty.to/lewwinski

— tiktok.com/@lewwinski. business

— youtube.com/@lewwinski

Look for Lewwinski or Lewwinski Business on other social media!

1.2 Types of business entities

Class objectives:

— Distinguish between private and public sector (AO2)

— Evaluate the main features of the following types

of organisations: sole traders, partnerships, privately held

companies, publicly held companies (AO3)

— Evaluate the main features of the following types of for-profit

social enterprises: private sector companies, public sector

companies, cooperatives (AO3)

— Evaluate the main features of the following type of non-profit

social enterprise: non-governmental organisations (NGOs) (AO3)

The main point of this chapter is to help you understand what the best form/type of business in a given situation is.

i. PRIVATE AND PUBLIC SECTOR

Distinguish between private and public sector (AO2)

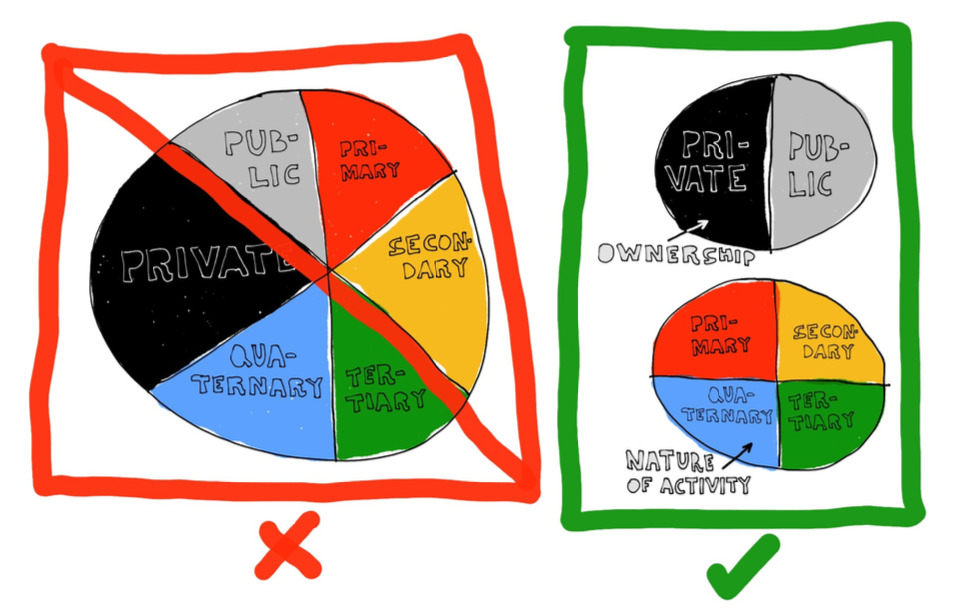

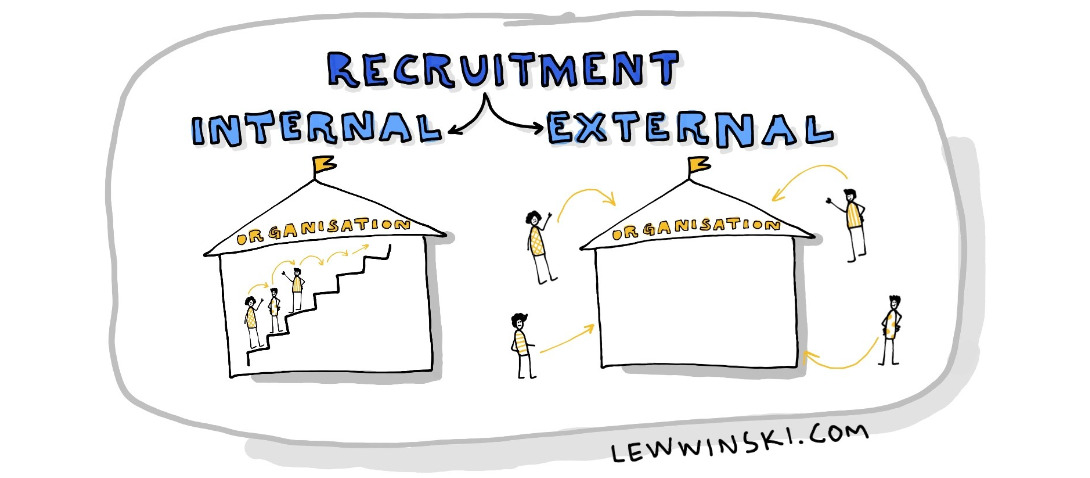

Sector in this chapter refers to part of the economy, just like in 1.1, but the sectors we are about to study are not sectors of industry, they are sectors of ownership. If you want to divide all businesses in any economy into four sectors of industry, you consider what this businesses are doing, i.e nature of activity. If you want to divide the same businesses in an economy into 2 sectors (private and public), you consider who they belong to. Thus, any business is in two types of sectors at the same time. For example, Volkswagen manufactures cars and belongs to shareholders, which means it’s in secondary sector (of industry) and private sector (of ownership). BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) is providing TV programmes and belongs to the UK government, which means that it’s in tertiary and public sectors. The illustration below summarises the main idea of this paragraph:

So, once we’re clear about the difference between sectors of industry and ownership sectors, let’s focus on public sector. Public sector refers to part of the economy that is comprised of organisations that are created and run by governments to provide public services, for example police, public transport, healthcare, education, infrastructure. Public sector organisations are mostly funded by tax revenue. They exist to make people’s lives better and they are not supposed to make profits. Even if they charge customers (for example, when you pay for a stamp in the post office) and make profits, these profits are not used to compensate to the owners of these organisations, because there are no owners/shareholders as such. These organisations belong to the government, i.e. to everyone, to all citizens. That is why, these “profits” are actually called surplus — the positive difference between revenues and costs in public sector organisations, that is reinvested in order to improve the services provided to citizens.

The best thing about public sector organisations is that they are socially-oriented and their essence is to help people. However, they are funded by taxes and they do not face much competition, so they tend to be quite inefficient most of the time. Public sector organisations do not have to fight for their existence and compete with other businesses because very often they are monopolies and are supported by tax revenues. Some examples of public sector organisations would be British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and National Health Service (NHS) in the UK, and United States Postal Service (USPS) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in the US.

Private sector refers to all organisations that are owned and created by individuals or group of people in order to satisfy needs and wants and provide goods and services. Most organisations in private sector are created to make money to their owners, which means that they are for-profit. However, there are organisations in private sector that are non-profit and are aimed at helping people, just like in public sector. Even though from mathematical perspective profit is the same as surplus (the positive difference between revenues and costs), we say “profit” when we talk about private sector, and we say “surplus” when we talk about public sector.

The best thing about private sector organisations is that they are efficient and innovative. They are forced to be efficient, innovative and creative, because if they aren’t, they’ll go bankrupt and they’ll be pushed out of the market by competitors and there is no one to back them up. Thus, they work hard to provide the best product to their customers and make sure everyone’s needs and wants are satisfied in the best possible way. However, most organisations in private sector are money-driven. They do not care about people as much as about profits. This trend is changing though and more and more organisations in the private sector commit to social goals. We will talk about it in more detail in the last part of this chapter. An example of private sector organisation can be pretty much any company you know: Apple, Google, Coca-Cola, Netflix, Burger King, etc.

Look up “list of countries by public sector size” on Wikipedia. Spoiler: Cuba’s public sector is 77.7% of their economy!

ii. TYPES OF ORGANISATIONS

Evaluate the main features of the following types of organisations: sole traders, partnerships, privately held companies, publicly held companies (AO3)

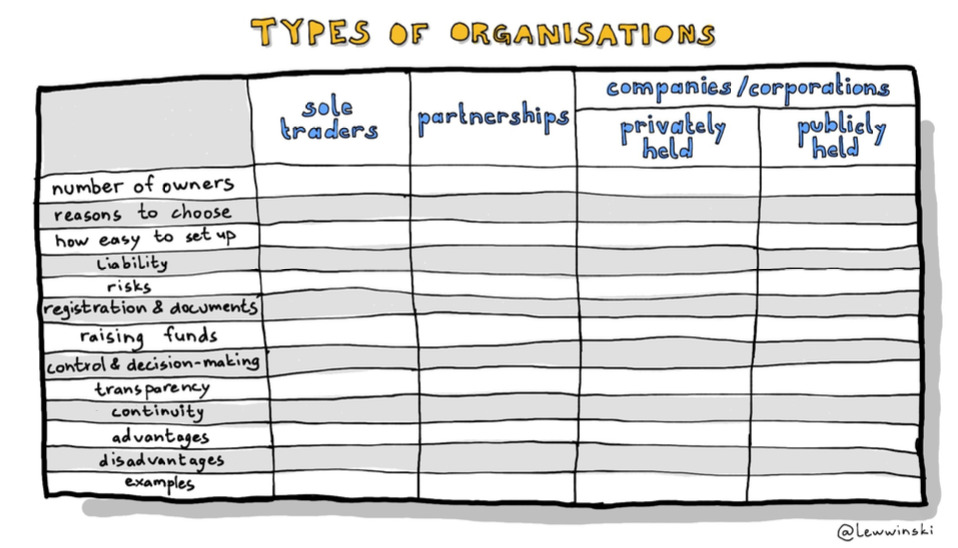

Can you please read the objective of this part of chapter again? Thanks. The objective is to learn to evaluate the features of different organisation types. Key words here are “evaluate” and “features”, which means that it is not enough to just understand what these organisation types are, it’s important to learn to express your opinion about them and justify it with facts. That is why, before we dive into the four types of organisations, we’ll learn how to evaluate them.

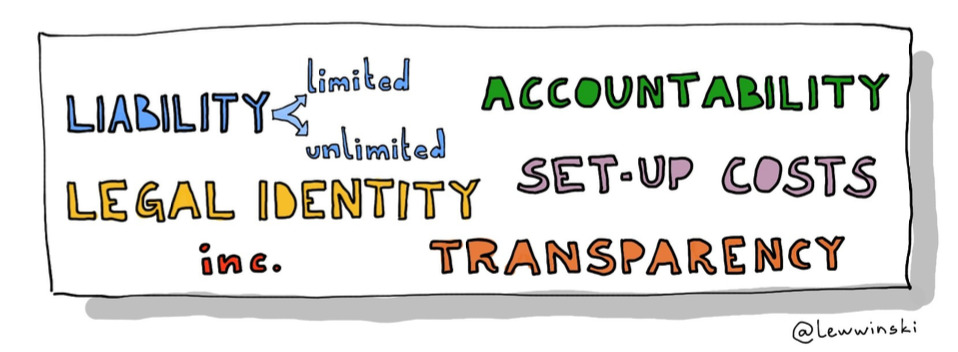

When we talk about any kind of organisation, we can use the same criteria to judge/evaluate them. For example, number of owners, reasons to choose the given type of organisation, how long it takes to register it, how risky and expensive it is, which documents are required for registration, how easy it is to raise funds, how difficult it is to control organisations and make decisions, what the chances of continuity are in case of owner’s absence and simply advantages and disadvantages. All of these are self-explanatory. In addition to the things mentioned above, there are a few more things that require a little bit more attention: liability, legal identity, incorporation, transparency, accountability and set-up costs. Why they require special attention? Because every year students ask me the same questions about these things and even if they don’t I can see that understanding of these terms could be improved. It might not apply to you personally, but I will still walk you through these terms.

Liability is the extent to which you risk losing your personal possessions in case of the business failure, it can be limited and unlimited. Unlimited liability means that you personally are completely, 100%, totally, fully, etc responsible for all the business debts and losses. Let’s say if (God forbid) your business goes bankrupt and you are unable to pay back $1000 to the bank where you took a business development loan, then the bank will make sure someone comes to your house and takes your personal belongings (TV, couch, PlayStation, etc) to make sure there is enough to compensate for that $1000 loan. Of course, this is a simplified explanation and example, but it’s perfect to illustrate what unlimited liability is for people who have just happened to read this term. It might sound scary, but unlimited liability usually refers to smaller businesses and people rarely end up losing their personal possessions. However, if you aim at long-term growth and building a multinational corporation, unlimited liability is clearly not the best option. Limited liability means that your responsibility for business losses is restricted by your initial investment, i.e your liability is limited by initial investment. For example, you buy some shares of Amazon today and costs you $500. If tomorrow Amazon (again, God forbid) goes bankrupt, you just lose a chance to get your $500 back, but nobody’s going to come to your house and take your personal belongings. If it does go bankrupt though and if it is unable to pay for its loans, then the bank will make sure someone comes and takes Amazon company’s belongings (office chairs, computers, building, etc). In other words, company’s assets will be seized, not personal assets of people who worked for Amazon. That’s all you need to know about liability at this point.

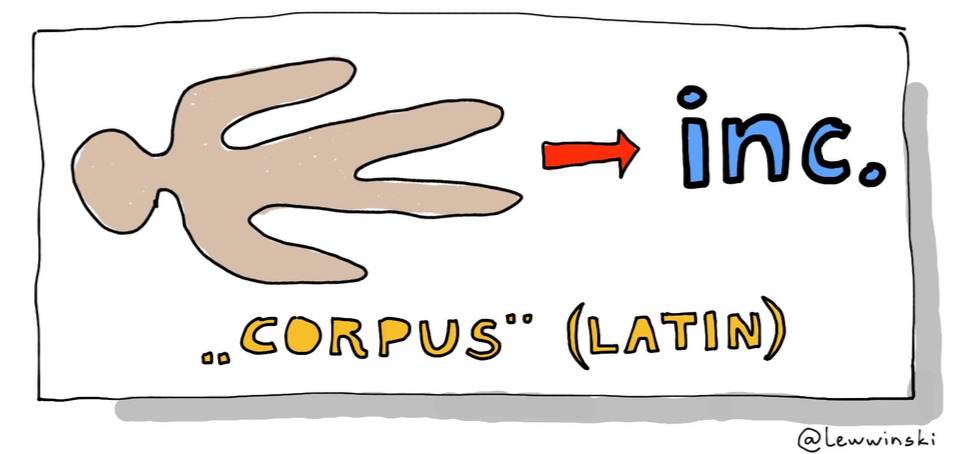

Legal identity is the formal registration of a human or non-human entity. For example, you are a real human being but unless you have a passport or another form of ID, you don’t exist from the legal perspective. So, some businesses, for example sole traders, do not have legal identity. Sole trader’s legal identity equals to the person’s legal identity. But companies, on another hand, have their own separate legal identity. Steve Jobs had his own identity, and Apple has its own. If you buy an iPhone and something doesn’t work the way it’s supposed to and you are refused a refund, then you will probably sue Apple, but not Steve Jobs, because Apple has its own legal identity. From the legal perspective, Apple is a real entity, as real as Steve Jobs. Now, if a business organisation does not have its own legal identity (just like sole traders), it means that they are unincorporated. If you buy a lemonade from a sole trader and get poisoned by it, you will sue this sole trader personally, not his business, because from legal perspective this sole trader and his/her business is one and the same entity. Companies, however, are incorporated — they do have a separate (from their owners) identity. Fun fact: “incorporated” comes from Latin word “corpus”, which means “body”. So if business and person are one and the same body — we call it “unincorporated” (no extra body). If a business has its own body that is separate from its owners’ body — we say “incorporated” (extra body created). So, if you see “inc.” after a company name, you know what it means now.

There are just three more terms before we move to sole traders, partnerships and companies. Transparency — the extent to which businesses have to disclose their financial data. Some businesses are really private and not transparent, they keep all the accounts to themselves and only share with the tax authorities. Some businesses, like publicly held companies (Apple, Amazon, Google, etc) are super transparent: they have to publish all their financial data several times a year. Want to see how much money they made? Just go onto their website and download an annual report. Accountability is the degree to which a person or business is responsible or answerable to someone. Partnerships, for example, have high degree of accountability, all the partners are accountable to each other. And finally, set-up costs refer to how much money you need to start a business in this or that form. Spoiler: setting up a business as a sole trader is usually the cheapest, but setting up a business as a company is usually the most expensive.

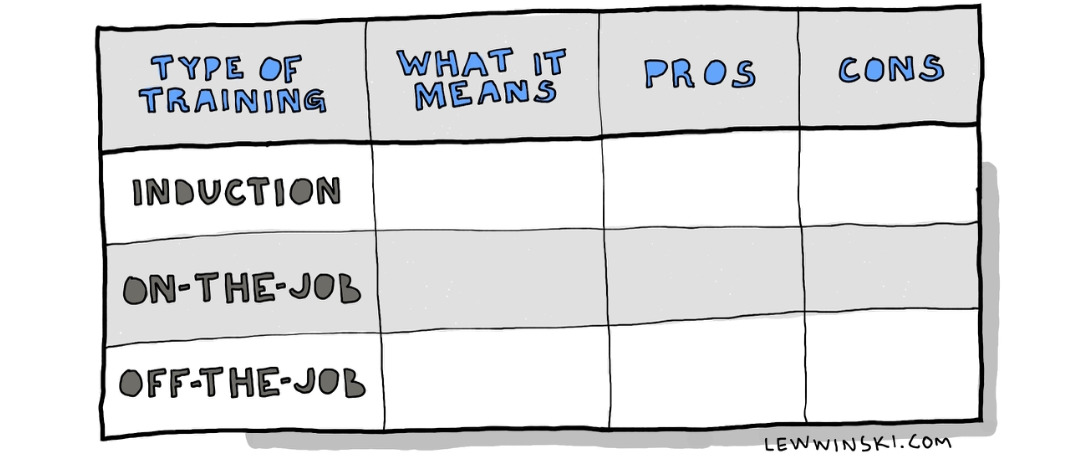

Now we’re ready to learn about sole traders, partnerships and companies. As you read about them, you might want to copy the table below and take notes in a systematic manner. If you were in my class, I would make you do it, haha. And by the way, I have already mentioned some of the things, so you may fill in some parts of this worksheet already.

Sole traders are people who run their businesses alone. This type of business does not have a separate legal identity, the owner and the business is the same entity, which means that sole traders are unincorporated. They also have unlimited liability, so sole traders are personally liable for all business losses with their own possessions. Sole traders do not usually focus on long-term growth, very often these are just people who do not want to work for anyone and want to control their life-work balance themselves. Very often they are also quite inexperienced, so the chances of failure for sole traders are pretty high due to lack of experience. Setting a business as a sole trader is relatively easy in most countries and only requires very few documents. Owners also get to keep all the profits and the tax is usually pretty low, or in some countries sole traders who earn less than a certain amount are completely tax-free.

Raising funds for this type of business is pretty difficult. Banks are reluctant to provide loans because they know that sole traders are likely to fail due to lack of experience. Mostly, sole traders are funded by personal savings. Sole traders are quite private, they do not have to disclose how much they earn to the public, thus they are not transparent. In terms of continuity, if something happens to the owner, then the business shuts down. No owner, no business. Sole traders cannot compete with large corporations because they cannot afford that kind of competition. However, sole traders can enjoy local monopoly. For example, if there is a small store in your neighbourhood and you want a drink and some snacks, you are very much likely to go to that little store. So this store will be a monopoly, but only within your neighbourhood.

Partnership is an association of two or more (usually up to 20) people who run a business together sharing the risks, workload, and profits. The most important document for a partnership is called partnership agreement (or deed of partnership), which is like a constitution, but for a partnership: it states how workload and profits are distributed among partners, what the procedure is for entering or leaving a partnership. Deed of partnership is signed by all partners. Some partners prefer not to run a business at all, but just to invest some money in exchange for a portion of profits. This type of a partner is called a sleeping partner (or a silent partner).

There are different types of partnerships but most of them have unlimited liability, which means, as you remember, that all partners are personally liable for losses of their business. They are also unincorporated, so the business’s identity is a combination of the owners’ identities, no new entity is created. Even though workload and risks are shared among all partners, so is decision-making and profits. The degree of accountability is relatively high and for a decision to be made all partners have to agree first.

Finance is still pretty difficult to acquire and banks are still quite reluctant to loan money to partnerships, but there is more finance available to partnerships than to sole traders simply because it is a numbers game: more people, more money. The main source of finance is still personal savings. Chances of continuity for this type of business are also higher than for sole traders because, again, there are more people involved.

Very often partnerships are a group of people who share similar expertise and who see synergy in working with others. For example, some dental school graduates might form a partnership and run a small clinic together: one of them could specialise in orthodontics, another one in surgery, the third one in dental hygiene. Altogether they can offer a varied service to their patients and at the same time they can share expenses for rent, electricity and equipment.

Companies are limited liability incorporated organisations. They have their own legal identity (owner ≠ business) and are a subject of law independently from their owners and people who work for them. The number of owners is, in theory, unlimited. Technically, every single person on earth can be an owner of the same company, which has never been the case in reality. Owners of companies are called “shareholders”. From now on, when I say “owner”, it implies sole traders and partnerships, when I say “shareholders”, it implies companies. The biggest risk for shareholders is losing their initial investment (the benefit of limited liability, remember?), that is why it is so easy for companies to raise funds (attract money) and grow, compared to sole traders and partnerships. People are not afraid of becoming shareholders as much as joining a business with unlimited liability. The price that companies have to pay for it is higher transparency, more procedures in registration and strict control from the government. Otherwise, companies would easily raise money by making people believe in them and then claim bankruptcy, spreading money among majority shareholders. As I mentioned earlier, in case of bankruptcy, company’s assets are seized, but shareholders’ and workers’ personal belongings have nothing to do with it.

Speaking of registration, the two most important documents for companies are Memorandum of Association and Articles of Association. The former includes all the conditions that are needed to register a company and the latter is like a constitution of a company, it states the main rules of the company. In addition to these two documents, companies are only allowed to start trading after they are provided with the Certificate of Incorporation, which is basically a trading license that allows companies to conduct business activity. The date it is issued is the official birthday of the company.

Shareholders do not have to run a business they own. If you buy Apple’s shares tomorrow, it does not mean you have to go to their office at 8am. However, some employees might also be shareholders at the same time. People who run the business on the top strategic level are Board of Directors (BOD) and Chief Executive Officer (CEO). BOD usually includes either some of the managers selected by shareholders, or majority shareholders (i.e. those who have most of the company’s shares), or people from outside the organisation who are selected by shareholders to represent their interests. What matters is that the job of BOD is to represent shareholders’ interests. Board gets together once a year for Annual General Meeting (AGM) to determine the long-term strategic plan for company development, but they also get together for Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM) in case an emergency requires directors’ attention. The person is in charge of actually running the company on a day-to-day basis is CEO.

Shareholders are eligible to a portion of company’s profits — dividends. However, dividends do not have to be paid at all, or do not have to be paid regularly, it all depends on the legislation and the company. Since shareholders have limited liability and companies are incorporated, the chances of continuity for companies are the highest among all companies. Even though Steve Jobs passed, Apple is still working. You might be surprised to know that Steve Jobs was once kicked out from his own company, because BOD was not happy with how he ran the company. Eventually, it was not a good idea and they hired him back, but the point is, continuity of the company is really high and does not depend on the absence of shareholders.

There are two main types of companies: privately held companies and publicly held companies. The key difference between them is that the former sell shares privately, only to those businesses and/or people they want to sell to, but the latter trade their shares on the stock exchange and potentially any human being of the legal age can become a shareholder. This is how Steve Jobs lost his job, even though he created the company. Once you become a publicly held company, you risk losing control to outsiders, who can buy the majority stake and tell you what to do. Mark Zuckerberg managed to avoid that by retaining the majority stake (the largest proportion of shares). By the way, it is a common misconception that the majority stake is 51% of company shares. It is the ultimate majority stake, but it is not a majority stake in most cases. Most of the time, it is enough to have more shares than other shareholders in order to have the final say, and it does not have to be 51% as long as it is more that other shareholders have.

Privately held companies, due to lower transparency and not having to publish that much financial data to the public, usually have a relatively low number of shareholders, compared to publicly held companies. They are very often owned by families. For example, Lego has been a privately held family business since 1932. Even though Christiansen family could have gone public many times, they prefer to retain control in the family and have not changed their type of business entity since 1932. Even though the transparency is relatively low and control over privately held companies is not likely to be lost to outsiders, it is quite difficult for shareholders to “cash out” if they want to leave the company and sell their stake. For publicly held companies, you just contact your broker and sell shares, but for privately held companies it has to be a private business deal, that is more difficult to arrange. Some examples of privately held companies are Lego, IKEA, Virgin Group, Chanel, Mars.

Publicly held companies cannot just become publicly held out of nowhere. All the publicly held companies were privately held prior to “going public” — making their shares available for purchasing to anyone (the public). After making a decision to go public, privately held companies have to go through initial public offering (IPO) — the process of selling their shares to the public for the first time. After IPO there is no direct control over share price. Share price is determined by the market laws of supply and demand. This process where shares are sold freely on the stock exchange is called flotation. So, publicly held companies have the greatest access to capital among all types of business entities, but at the same time they are the most transparent type of business organisation. Examples of publicly held companies are Apple, Coca-Cola, China Mobile, HSBC, Microsoft, Nike, etc.

Watch the full video class for this topic to learn some fun facts about IPO at boosty.to/lewwinski or watch extracts from the video class about companies on my TikTok and other social media. If you know something fun and interesting about companies in your country or all over the world, please share in the comments!

iii. SOCIAL ENTERPRISES

Evaluate the main features of the following types of for-profit social enterprises: private sector companies, public sector companies, cooperatives (AO3); Evaluate the main features of the following type of non-profit social enterprise: non-governmental organisations (NGOs) (AO3)

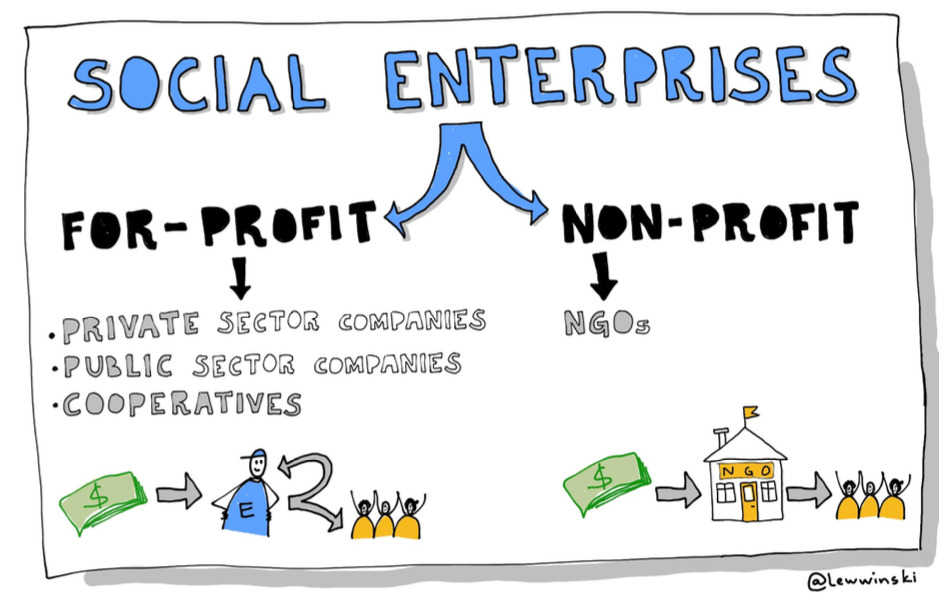

Keep in mind that even though this part of chapter is just called “social enterprises”, there are two objectives (see above) and there are two different types of social enterprises: for-profit and non-profit. To make it clear and easy to understand, look at Figure 7.

Very often students think that social enterprise and non-profit organisation is the same thing. Or, they think that there are 4 types of business entities: sole traders, partnerships, companies and social enterprises. None of these two ideas are right. Social enterprise is an organisation that has social wellbeing as its main goal, instead of making profits. That is why it is not the same as non-profit organisation. Social enterprises can make profits, or cannot, what matters is just the social wellbeing bit. Is social enterprise the fourth type of business entity in addition to sole trader, partnership or company? Wrong! Social enterprise can take any form: some social enterprises are sole traders, some are partnerships, some are companies. Cooperatives, that we’ll talk about in a moment, are social enterprises by their nature, because they are created for the benefit of certain communities. So, to recap, social enterprise is not a legal type of business entity (sole trader, partnership, company), it is a characteristic of an organisation.

Now, back to Figure 7 and the first type of social enterprise — for-profit private sector companies. By now, you should already understand what for-profit private sector company is, so I am not going to define it. If you are struggling with understanding what it is, it’s totally okay, just read the chapter again or try another way of perception and watch the video class for this topic at boosty.to/lewwinski. So, we’re not just talking about for-profit private sector companies now, we’re only talking about those of them, that are social enterprises.

These companies make profits, even though it is not their prior objective. Profits are used more as a tool to achieve socially important aims and compensate to owners at the same time. Other than that, these organisations have the same features as private sector companies.

The example of this type of social enterprise is Smenka Show and Geek Teachers that are run by two social entrepreneurs from Russia — Arina and Masha. Smenka Show is a social enterprise that raises money to renovate classrooms in schools. In the following illustration you can see the “before and after” pictures. Geek Teachers organise events for teachers to inspire positive change in education. So, what Masha and Arina do is a business, it earns profits, but community benefits from this business as much as (or even more than) Masha and Arina. I also asked the girls about the pros and cons of running a social enterprise and I will share it with you a bit later when we talk about theoretical pros and cons, so that we can compare these with what real entrepreneurs say. So keep reading.

The second type of social enterprises is for-profit public sector companies. Again, you should understand what it means by now. These organisations are the same as private sector companies that we’ve just discussed, but they operate in public sector, which means that they are created and run by government, which also means that most of them are focused on public services: medicine, infrastructure, transport, education, etc. The example of for-profit public sector companies could be waste sorting and recycling plants in Sweden. As you probably know, in Sweden they are aiming at recycling as much as possible and at having zero waste, so there are a lot of waste management companies. They:

— are trying to benefit everyone by recycling waste,

— make profits,

— are created or funded by the government,

which means that they have all the essential features of for-profit public sector companies.

The last type of for-profit social enterprise is cooperatives — “an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprise” (definition from International Cooperative Alliance). So, basically, a group of people decide that they need an organisation that will make their lives better. This is the key feature of a cooperative, by the way — it is created and run by its members for their benefit. For example, people in the neighbourhood decide that they need an organisation that will take care of maintenance, waste management, provision of internet and cleaning in their neighbourhood. So all the neighbours join this organisation, run this organisation, and enjoy the benefits of this organisation. That would be an example of a residential (housing) cooperative. There are also agricultural, consumer, financial and many other types of cooperatives. What all of them have in common is that they are created and run by their members for their own benefit and they are run in a democratic manner: votes for decisions are taken directly or through representatives, which is great on the one hand, but prolongs decision-making, on the other hand. I’m quite sure you heard about SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) — it is a cooperative of banks that created a messenger to make money transfers easy and simple for their own benefit, which also benefits the clients as well.

The last type of a social enterprise is non-profit and it is NGOs (non-governmental organisations). This term first appeared shortly after the Second World War in the United Nations and there is no universal fixed definition for NGOs, so the understanding of NGOs differs from country to country. What all NGOs have in common is that they are usually non-profit, they have public trust, they usually address public well-being issues, such as health, environmental protection, human rights. NGOs can also be lobbying groups and political parties. And of course the main feature is that they are not run by the governments. Some examples of NGOs could be Greenpeace, Amnesty International and Oxfam. Check out the websites of these organisations to learn more.

So, now you know the four types of social enterprises, three of which are for-profit and one of which is non-profit. Now it’s time to look back at objective and do what it asks: evaluate. The advantages of social enterprises are:

— They result in customer loyalty, because people to buy something from “good companies” because it makes them feel good when they do so, it makes them feel they contribute to something meaningful by supporting social enterprises.

— In addition, social enterprises are by definition socially and economically sustainable which impacts communities and environment positively, or at least there is no harm.

— Lastly, social enterprises bring positive change.

On the other hand, social enterprises might experience high compliance costs (costs of being ethical). For example, you are a committed social enterprise and you have a choice of two suppliers: one is using eco-friendly materials but charges more and another uses plastic but charges less. You are very much likely to go for the expensive option because it is in line with social entrepreneurship principles, i.e the costs of being a social enterprise might be higher. In addition, very often social enterprises are not really economically sustainable and rely on donations and irregular funding. And lastly, social enterprises are usually transparent and democratic, which might result in prolonged decision-making.

The advantages and disadvantages above are too general, theoretical, and they do not necessarily apply to all social enterprises. In order to give you a more practical perspective, I asked Arina and Masha from Smenka Show and Geek Teachers what the pros and cons and opportunities and challenges for them personally as social entrepreneurs are and here’s what they said:

The benefits are opportunity to have an impact on people’s life quality and inspiring people for positive change. However, the first drawback is that traditional promotion and targeting do not work, you have to reach people. If you sell shoes, it’s pretty easy to understand who your customers are and target ads for them in social media, for example. But with renovating classrooms, you have to reach teachers, school principals and community and you start from scratch with every new school. In addition, income is hard to forecast. Also, even though you’re doing something good and you are socially focused, some people don’t need it and they say “we’re fine the way it is, we don’t care”. And lastly, people do not always understand why they should pay for some good deeds. They think that all good things should be free, for some reason.

I hope that was really helpful and I really appreciate the comment that Arina and Masha gave. Donate to Smenka (smenkashow.ru)!

That is the end of 1.2.

Look back at class objectives. Do you feel you can do these things?

— Distinguish between private and public sector (AO2)

— Evaluate the main features of the following types

of organisations: sole traders, partnerships, privately held

companies, publicly held companies (AO3)

— Evaluate the main features of the following types of for-profit

social enterprises: private sector companies, public sector

companies, cooperatives (AO3)

— Evaluate the main features of the following type of non-profit

social enterprise: non-governmental organisations (NGOs) (AO3)

Make sure you can define all of these:

1. Public sector

2. Private sector

3. Surplus

4. Profit

5. Liability

6. Limited liability

7. Unlimited liability

8. Legal identity

9. Incorporated

10. Unincorporated

11. Transparency

12. Accountability

13. Sole trader

14. Partnership

15. Deed of partnership

16. Sleeping (silent) partner

17. Privately held company

18. Publicly held company

19. Shareholders

20. CEO

21. BOD

22. AGM

23. IPO

24. Flotation

25. Stock exchange

26. Dividends

27. Memorandum of association

28. Articles of association

29. Certificate of incorporation

30. Social enterprise

31. Private sector company

32. Public sector company

33. Cooperative

34. NGO

35. Compliance costs

Check out these resources to boost your BM knowledge and skills:

— boosty.to/lewwinski

— tiktok.com/@lewwinski. business

— youtube.com/@lewwinski

Look for Lewwinski or Lewwinski Business on other social media!

1.3 Business objectives

Class objectives:

— Distinguish mission and vision statement (AO2)

— Analyse common business objectives: growth, profit,

shareholder value, ethical objectives (AO2)

— Discuss strategic and tactical objectives (AO3)

— Examine corporate social responsibility (CSR) (AO3)

The main point of this chapter is to understand the importance of business objectives — one of the main concepts in business management.

i. VISION AND MISSION

Distinguish mission and vision statement (AO2)

Vision and mission are statements that a business makes in order to prioritise objectives and let stakeholders know what business “is about”. Vision statement is a declaration of business’s aspirations, i.e. a picture of success for the business. Usually, vision statement is set only once and does not change. Mission statement is a declaration of a business’s purpose, i.e. reason for being of a business. Mission can be changed, revised and updated.

I will provide two examples of vision and mission: one will be hypothetical and not related to business, just to make it easier to understand; the other one will be Google’s vision and mission. So, if you’re a very ambitious and hardworking student, your personal vision can be “being the best student in the world” and mission might be “to study hard”. Vision is something that is quite vague and hard to quantify, and yet a good thing to work towards. It’s a good aspiration to be the best student in the world, right? Mission “to study hard” is your purpose on the way to the vision, it is not something that can be achieved, it is something that you do, it’s the reason for your existence as the best student. I hope it helps to understand the major difference between vision and mission.

The realistic business example would be Google. Vision: “To provide access to the world’s information in one click”. Mission: “Organise the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”. As you can see, reality is quite different from theory… More about that in the following paragraphs about pros and cons of vision and mission statements.

On the one hand, vision and mission serve as assessment criteria (just like in your IA) for the business and help to evaluate business decisions and objectives. For example, from the manager’s perspective, when he/she is uncertain about which decision to make, he/she could consider which decision is in line with vision and mission and go for this decision. At the same time, vision and mission help to motivate staff, because knowing why you work and having a meaningful work is one of the main motivators. It can also attract customers, because they like to buy from businesses that are doing something great, rather than simply sell products. Think about Nike and their ads: do they really sell shoes or do they sell values and lifestyle? And lastly, vision and mission quickly let all stakeholders (customers, employees, managers, investors, shareholders) know what the business is about.

On the other hand, both vision and mission are quite unclear and sound like “we support all good things and we don’t support all bad things”. Even though businesses are sometimes from completely different industries, their vision/mission often follow this “formula”. Sometimes, vision and mission are so vague and unclear on purpose, because the more vague they are, the more difficult it is to agree or disagree with them and the more flexible managers can be, because they have a lot of freedom in interpreting vision and mission. And lastly, very often these statements are written as a public relations (PR) trick to impress stakeholders and they are not really used to guide decisions. On top of that, in reality, many businesses do not distinguish between vision and mission and they only have one statement that is called either vision or mission.

So, overall, vision and mission are really useful statements that can guide business decision-making, but only if they are sincere and only if they are made mindfully, not just to “tick the box”.

ii. COMMON OBJECTIVES

Analyse common business objectives: growth, profit, shareholder value, ethical objectives (AO2)

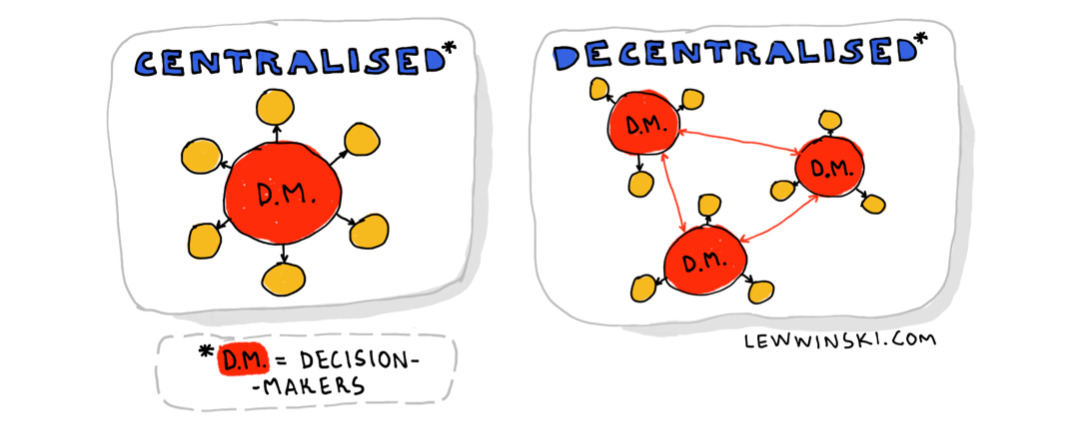

For starters, we can’t just talk about objectives right away, because it is extremely important to understand the role objectives play and their place in business decision making. Actually, “common objectives” will be the last thing we’ll talk about in this part of chapter, so please be patient. For now, we’ll talk about GOST (it’s not a typo, there is no “H” in this acronym): goals, objectives, strategies and tactics.

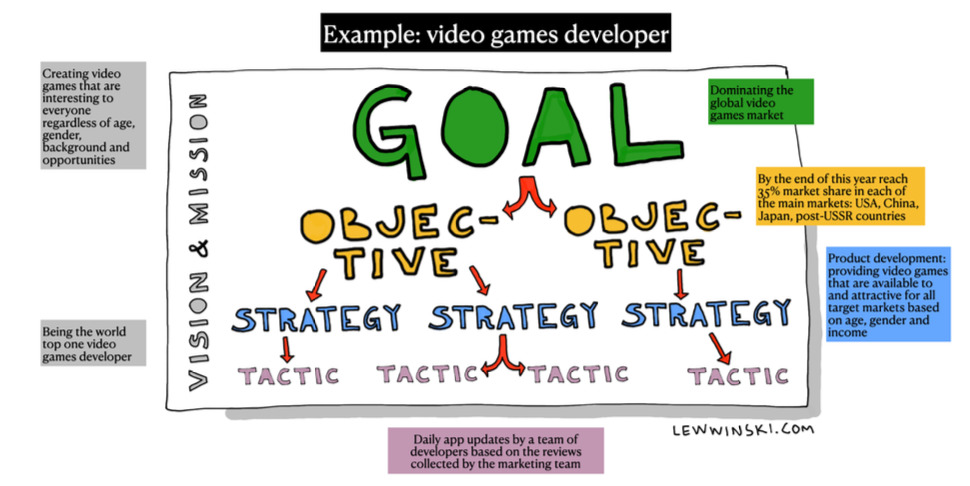

So, you already know what vision and mission are. As you can see in Figure 1, vision and mission are like a soup, where goals, objectives, strategies and tactics boil. Vision and mission underpin business and particularly decision- making at all levels. Then, inside this “soup” there are four other things (goals, objectives, strategies and tactics) that I suggest you remember in this order (GOST), because you can consider it a hierarchy. The picture in Figure 2 can help you understand it better.

Goals — what business wants to achieve in the long-term. Objectives — clearly defined short-term or medium-term tasks that a business sets in order to achieve goals. Strategies — medium-term or long-term plans, methods, approaches, schemes that are used to achieve goals and objectives. Tactics — short-term or medium-term actions that need to be taken in order to achieve objectives.

As you can see from the definitions above, one things flows from another, hence the hierarchy: objectives are set to achieve goals, strategies are used to achieve objectives and goals, tactics are used to achieve objectives.

To deepen our understanding of goals, objectives, strategies and tactics, let’s consider an example of a hypothetical video games developer company.

So, the first thing here is vision: “Being the world top one video games developer”. This is what drives the company at all levels. This is what helps to determine everything (goals, objectives, strategies, tactics) and this is what guides all decisions. The next thing to consider is mission: “Creating video games that are interesting to everyone regardless of age, gender, background and opportunities”. This is the reason for company’s existence, this is the “why” of their actions. Similar to vision, it guides all the decisions at all levels. Then, there is a goal that is set by senior management: “Dominating the global video games market”. It is more specific, than vision, it is realistically achievable, it is long-term, and yet it is not as specific as the objective (that is set to achieve the goal): “By the end of this year reach 35% market share in each of the main markets: USA, China, Japan, post-USSR countries”. As you can see, objective is super specific and concrete, compared to the goal. Later in this chapter we will learn a simple rule how to make a good objective (keep reading). Usually, there are several objectives that are set to achieve one goal. The next thing on the list is strategy: “Product development: providing video games that are available to and attractive for all target markets based on age, gender and income”. This is a plan on how to achieve the objective. Again, it does not have to be one objective and one strategy, there can be multiple of each. And finally, we have a tactic of “daily app updates by a team of developers based on the reviews collected by the marketing team”, which is a day-to-day routine plan on how to make objective happen.

So, by now, I hope, it is crystal clear where objectives belong to and what their role is. Objectives are the most specific of all things in GOST hierarchy, including vision and mission. Even though they are not on the top of the hierarchy, I would argue that they are the most important due to their concrete nature.

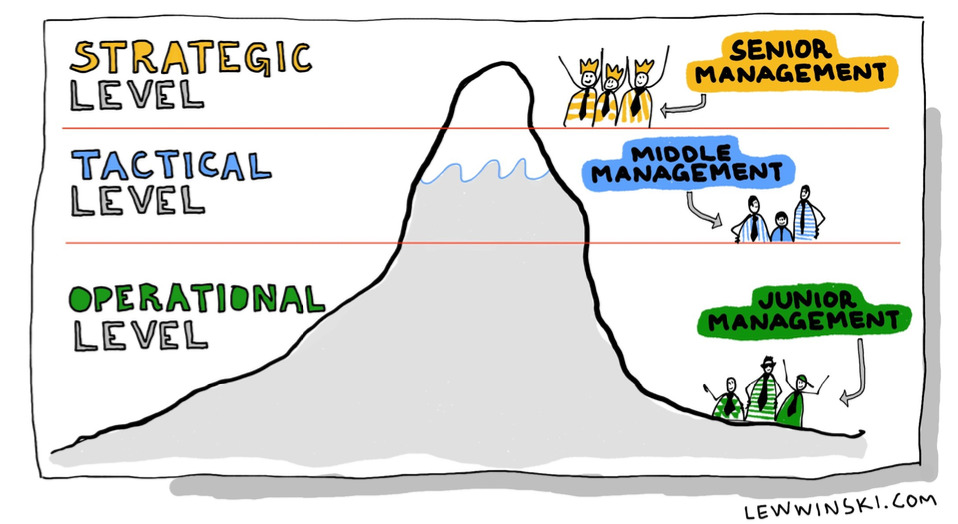

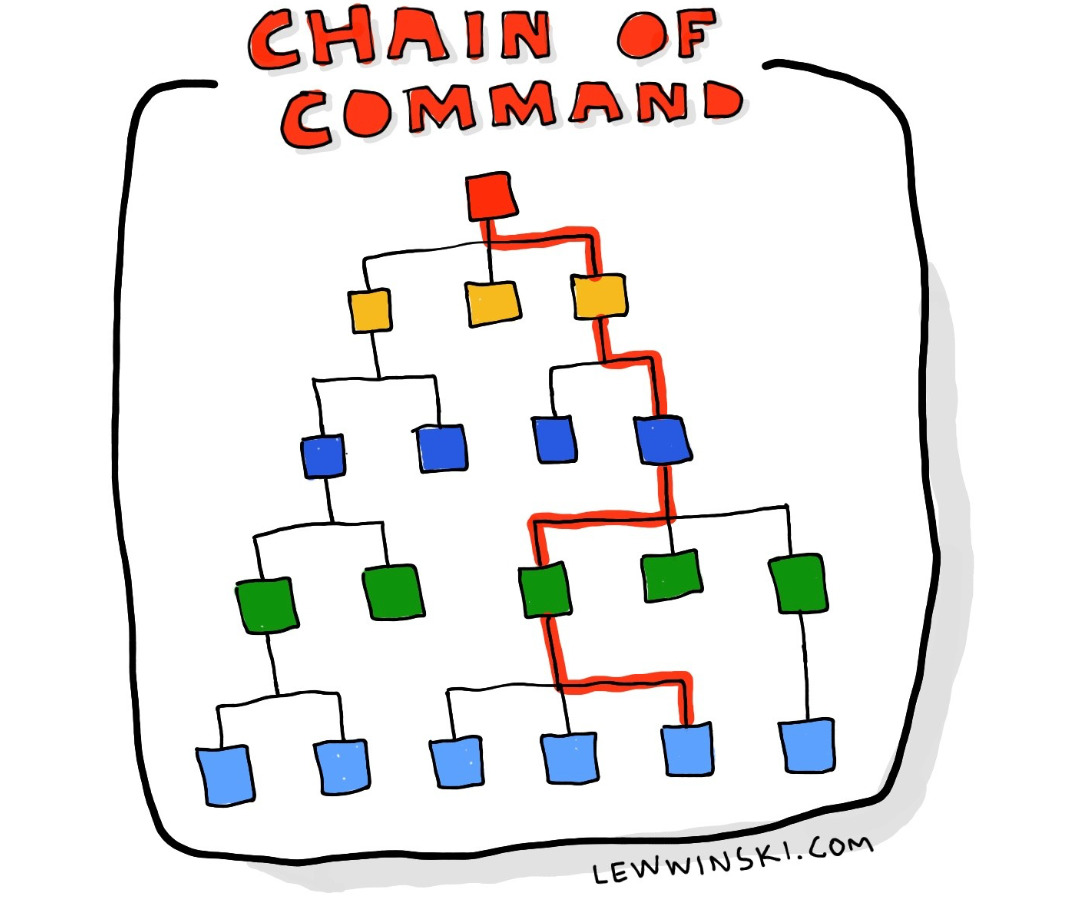

I’ve already mentioned earlier that goals are set by senior management and you might ask: “what are other types of management in an organisation?”. The brief answer to that question is in Figure 4.

The top level of management is called strategic level. Decision-makers at this level are senior managers. They usually set the long-term goal and define corporate strategy, that determines the market in which the business operates (senior management). For example: “ten thousand students competitive one-million-RMB market of international high school education market in Beijing”. Describing a market is not an easy task, because it has a lot of characteristics (more about that in Unit 4), but once market is determined and clear, decisions and strategies are much easier to set.

The level of management in the middle of the hierarchy is called tactical level. Middle management is in charge of decision-making at that level and they usually determine generic strategy, that determines methods of achieving competitive edge. Competitive edge is “how our business is better than others”, “why would people buy from us, not from our competitors”. Middle managers are usually people who do most work in the company even though they do not get highest rewards. They are between two fires: they have a lot of subordinates on lower levels of the organisation and yet they are accountable to senior management.

The lowest level of the company is called operational level. This is a day-to-day level that is in charge of making goals, objectives, strategies and tactics happen on a daily basis. Junior management is in charge of decisions at that level and they determine operational strategy that defines what company needs to do on day-to-day routine level and how to make generic and corporate strategies happen.

As you can see, there can be overall GOST for the entire organisation, and at each level they an have their own GOST, specific to their level only. Vision and mission, however, as well as overall GOST are the same for everyone at all levels.

So, remember these sequences:

— strategic level — senior management — corporate strategy,

— tactical level — middle management — generic strategy,

— operational level — junior management — operational strategy.

Now it’s time to warn you again that all the information above is from the perfect theoretical world where everyone follows the same rules and uses the same terminology which is, of course, not the case in reality. Very often, businesses do not distinguish between the three different strategies, very often “generic” and “corporate” are used synonymously, very often “business strategy” is what businesses call any of these three. And finally, strategies are not limited to these three. There are plenty of strategies that we will learn later in the course. A lot of them will come from the business tools. Be mindful of the theory and of its real-life interpretations and you’ll be the best decision-maker ever!

Now it’s finally time to talk about the common business objectives, which are actually the title of this part of chapter. I hope you understand that all this information above is essential for understanding the common business objectives. Without this info, common objectives are quite meaningless. So, common business objectives:

— Profit — the difference between revenues and costs (more in Unit 3).

— Growth — achieving an increase in one/some of the following: market share, total revenue, profit, capital employed, size of workforce, volume of output. Ultimately, growth results in higher profits (more in 1.5).

— Shareholder value refers to what shareholders get through company’s ability to increase market capitalisation (and thus share price) and/or dividends (through increasing the profits) (more in Unit 3).

— Ethical objectives refer to the tasks/targets that go beyond profit-making and are in line with moral behaviour, sustainability and CSR (more later in this chapter).

I love it how we had to go through about 1000 words before we could read one paragraph that tells us that more information is yet to come, haha. Believe me, we needed it. If you made sense of everything you read, you learnt a lot of important stuff about business and decision-making that you can go ahead and use right now. Thanks for your efforts, appreciate that!

iii. STRATEGIC AND TACTICAL OBJECTIVES

Discuss strategic and tactical objectives (AO3)

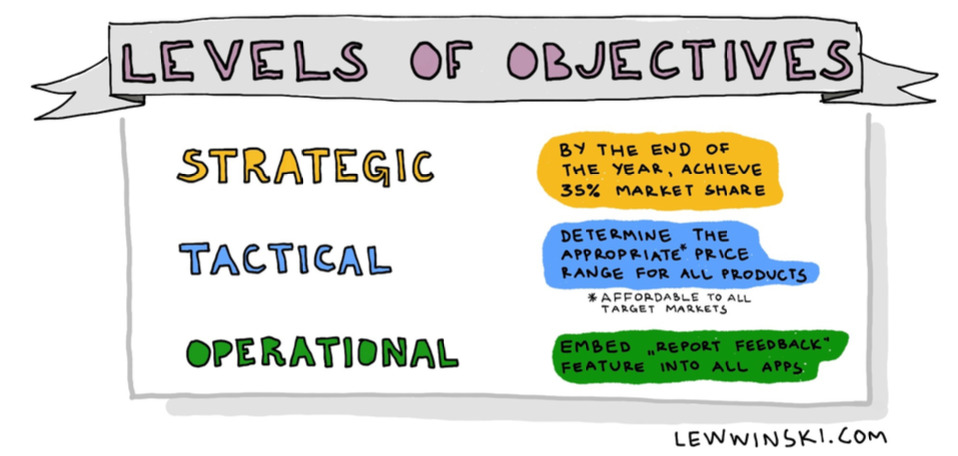

As you already know from the previous chapter, there are three levels in an organisation: strategic, tactical and operational. There are objectives at each level. Strategic objectives apply to the entire organisation, and they determine tactical objectives and operational objectives. Have a look at the examples of all three types of objectives in Figure 5.

Based on the second (the most important) part of the chapter, you should have no problem understanding the levels of management and levels of objectives, but our objective for this part of chapter goes beyond understanding. Our objective here is to learn to evaluate strategic and tactical objectives. So, let’s cut to the chase.

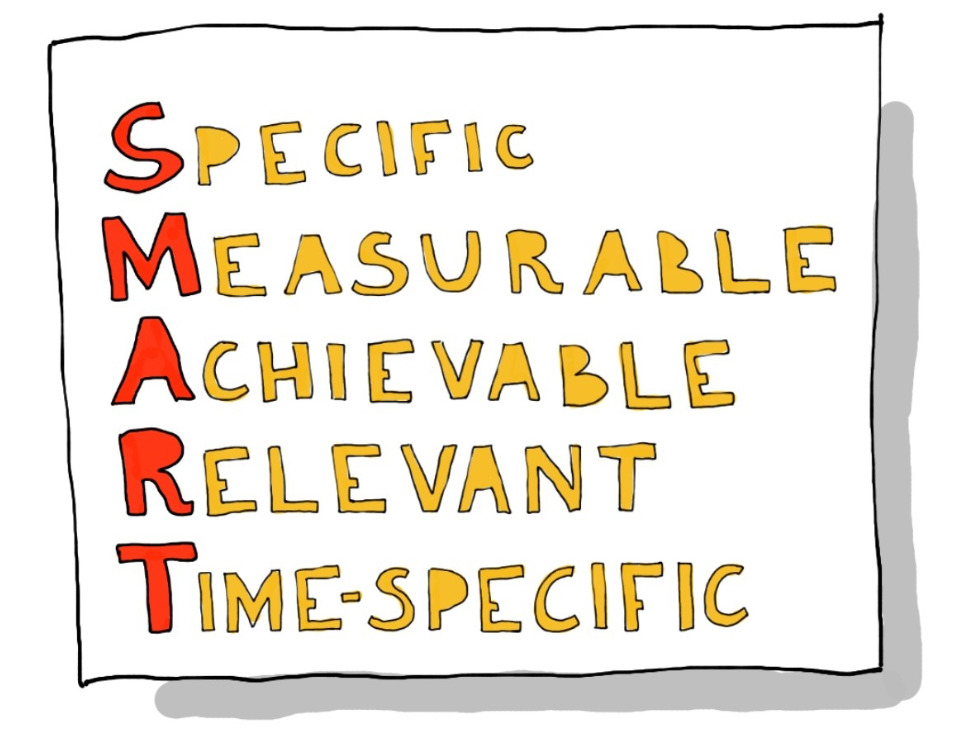

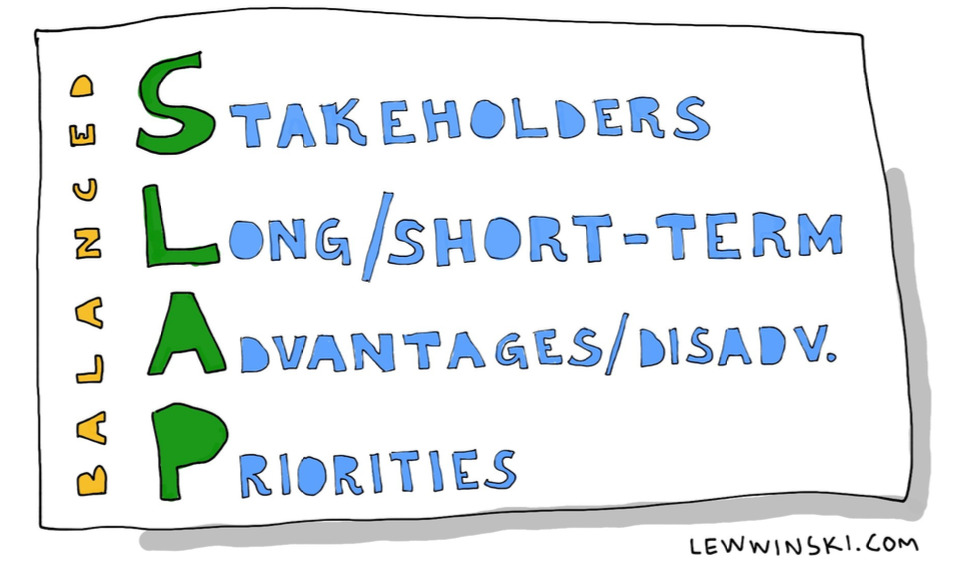

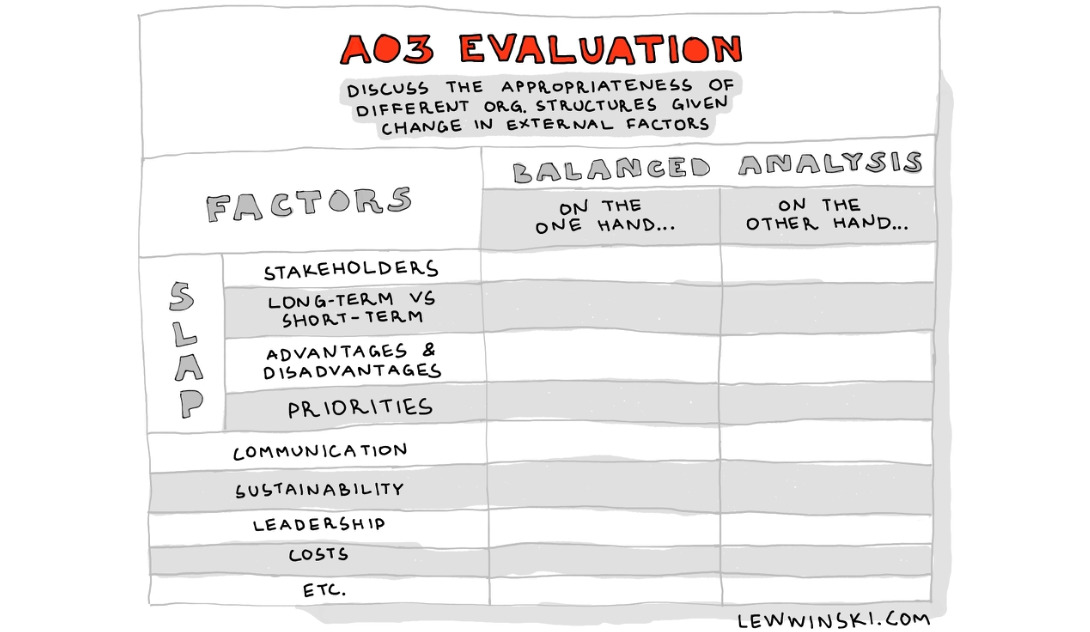

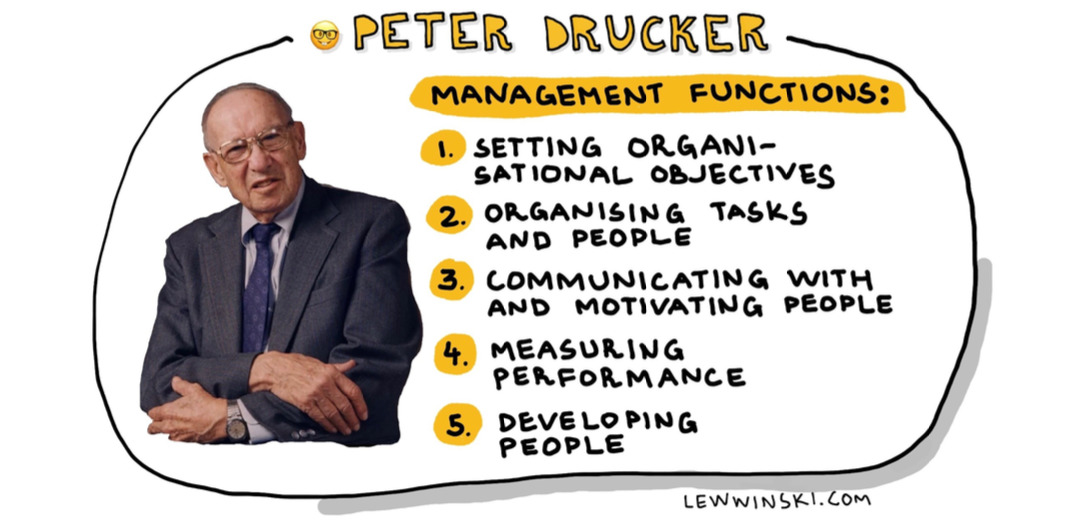

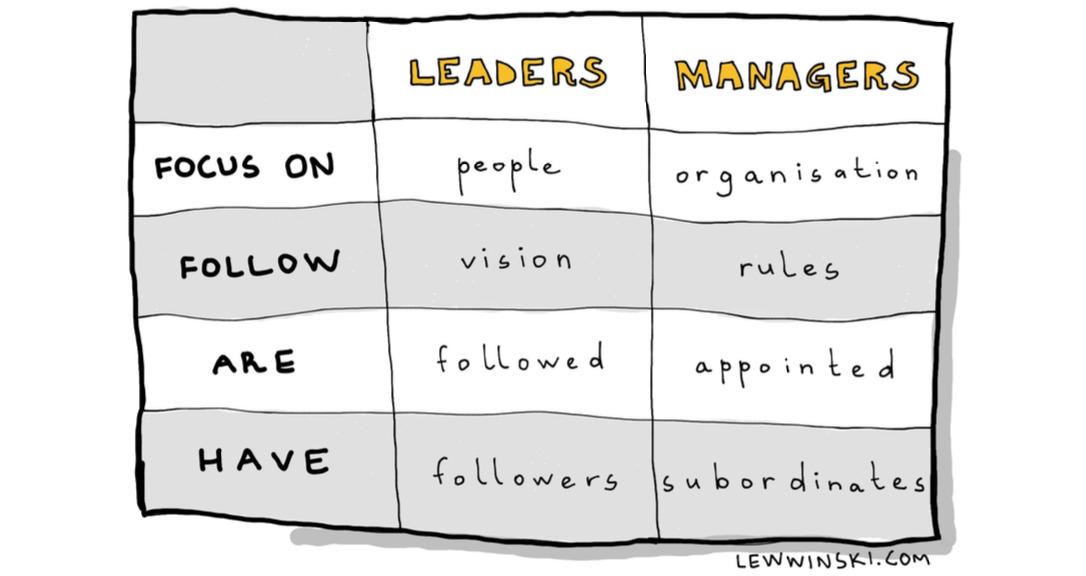

I am going to teach you two ways to evaluate strategic and tactical (and actually any other) objectives. The first way is called SMART, the second one is called SLAP. SMART objectives is a super cool super useful rule that can apply to any objective (not only business-related). This rule was designed by Peter Drucker, whose name you have to know and whose books you are highly encouraged to read if you are interested in Business Management. The SLAP rule is what personally I use to teach my students how to answer AO3 evaluation questions. I don’t really remember how I learnt about SLAP and who invented this rule, but all of my colleagues who teach Business Management know and love this rule. I wish I knew who to give credit to.

As you can see from the Figure 6, a SMART objective is the one that is specific, measurable, achievable, relevant (or realistic) and time-specific. My favourite elements are measurable and time-specific because they change objective dramatically from a vague unclear statement into a concrete target. For a video games developer company, objective “to be the best” is not SMART, but “by the end of this year reach 35% market share in each of the main markets” is SMART. I like this rule for its simplicity and significance.

With regards to SLAP, this rule applies to any Business Management AO3 question, not just to objectives. These four letters refer to four ideas/paragraphs that you might utilise/write in your AO3 response:

1. “S” (stakeholder implications): in this paragraph you can consider implications to an internal stakeholder group and compare these implications to those of another external stakeholder group, or you can simply analyse costs and benefits to one stakeholder group. Make sure your analysis is balanced (on the one hand… on the other hand…). We’ll learn stakeholders in more detail later in 1.4, but all you need to know now is that stakeholders are people or groups of people who are interested in and affected by a certain business. Internal stakeholders are within a business (shareholders, mangers, etc), external stakeholders are outside of the business (local community, government, etc).

2. “L” (long-term and short-term implications): you can compare and contrast the short-term and long-term effects of a certain advantage or disadvantage, or of costs and benefits, or of an implication. What makes your analysis balanced is the contrast between short-term effects and long-term effects.

3. “A” (advantages and disadvantages): here you can choose any perspective and simply consider pros and cons of it.

4. “P” (priorities): in this paragraph you conclude the analysis in the paragraphs above by making a judgement against the priorities, (mission, or vision, or an assumption).

It’s okay of you feel confused now. This sort of thing is better to be explained face-to-face with step-by-step guidance, so your teacher should be of great help. One more thing I can do to help you better understand SLAP is provide an example.

Let’s say Jin is running a coffee shop in her neighbourhood and she set the following objective: “become the best coffee shop in the neighbourhood”. Our task is to evaluate this objective. We are going to use SMART and SLAP for evaluation.

SMART: If we apply SMART rule to Jin’s objective we’ll see that objective is achievable and relevant/realistic, but not specific, measurable and time-bound.

Stakeholder implications (S): If she sets this objective, Jin (an internal stakeholder) will have to focus on developing a unique selling point to compete with big coffee chains. Community (external stakeholder) might benefit from the personal touch and customisation based on their needs, that large coffee chains aren’t able to offer.

Long-term and short-term implications (L): In the short term, adopting this objective will result in investment that leads to negative net cash flow. In the long term, if the objective is reached, Jin’s coffee shop can enjoy local monopoly power (monopoly, but only within the neighbourhood).

Advantages and disadvantages (A): On the one hand, organic growth, less risk. On the other hand, “short-termism”, which means that the objective does not have long-term orientation.

Priorities (P): Since Jin just wants to keep herself busy at daytime and make some cash to support her family, objective is appropriate but it needs to be made SMART in order to make it more attainable and quantifiable. It’ll be easier to measure success with a SMART objective.

Let’s summarise this part of chapter. You know the levels of management and you know the levels of objectives in an organisation. You’re expected to learn how to assess only strategic and tactical objectives, and now you know that tools like SMART and SLAP can help you do that effectively. Well done!

iv. CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY (CSR)

Examine corporate social responsibility (CSR) (AO3)

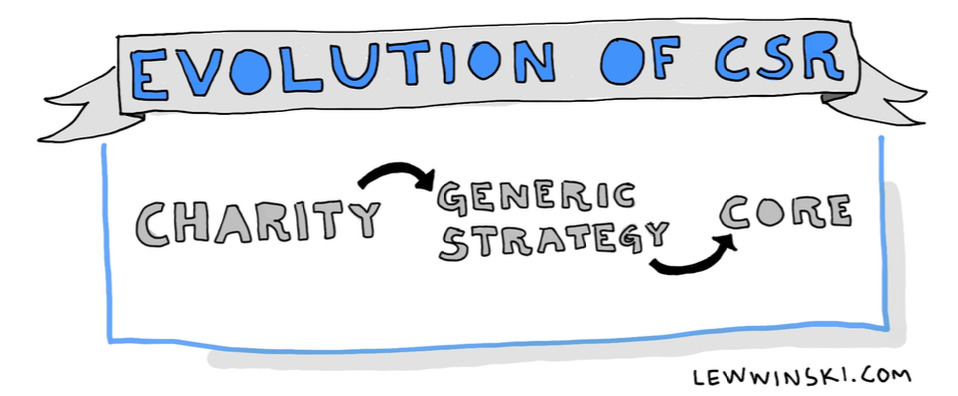

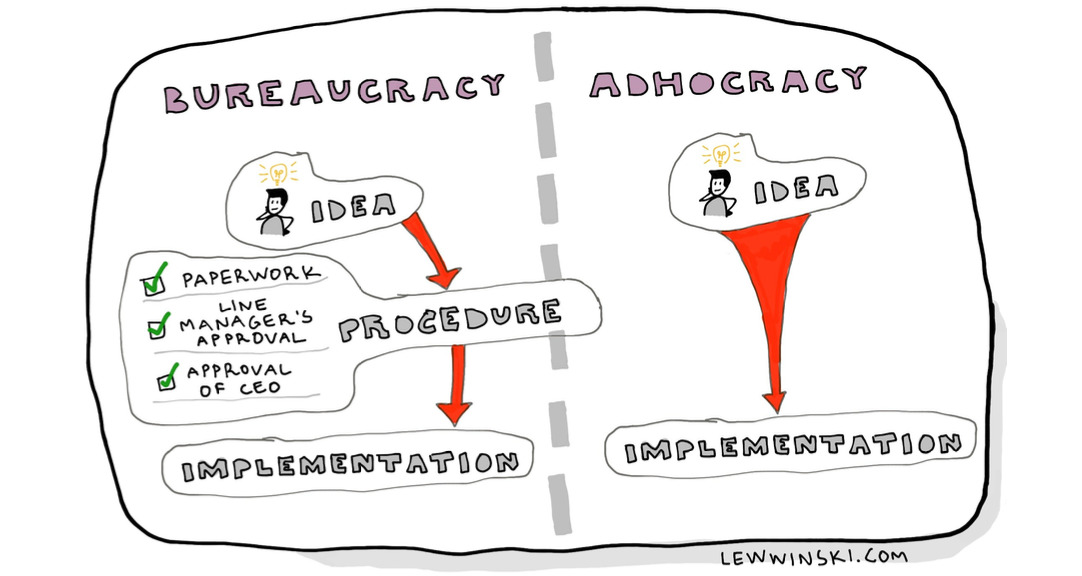

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a commitment to benefiting (or at least not harming) the society and environment that is achieved through setting ethical objectives. CSR is not a legal obligation, it is a positive trend that businesses set. It means that if some businesses do not commit to CSR, they are not doing anything illegal, but it’s not cool. Nowadays nearly all businesses try to adhere to CSR principles: sometimes it’s superficial, sometimes it underpins the entire organisation, but it is really a big trend nowadays.

There is no agreement about when CSR started. Actually, some businesses were socially responsible even centuries ago, but it was not called “CSR” back then. CSR as a business term emerged around 1960s. Originally, CSR was similar to occasional charity (businesses just donated some money for good causes every once in a while to look good), then it turned into generic strategy (CSR was a way of gaining competitive advantage: “all businesses are just earning money, but we really care about people”), and nowadays CSR evolved into a principle that underpins all levels of the business (whenever business decisions are made, they are analysed through the prism of CSR: “what is the benefit that this decision will bring to the community? Is there any harm that comes with this decision?”).

There are several reasons why businesses commit to CSR. As I mentioned earlier, sometimes it’s just to enhance the brand image (“greenwash” the company), sometimes it’s a business strategy (criterion for decisions), sometimes it’s pure altruism (just a desire to help people), especially when it comes to social enterprises and NPOs. Regardless of the reasons, even though some businesses only do it for commercial reasons, it is a positive trend that puts extra pressure on businesses and prevents them from careless decisions that might harm the environment and local communities. This CSR trend impacts supply chain and all stakeholders and pushes all of them to be responsible “corporate citizens”. Nowadays, especially in developed economies, CSR is not an exception. An exception is its absence.

With regards to evaluation of CSR, some of the advantages of it are improved brand image, increased customer loyalty, staff retention and an extra incentive to join the business for potential job seekers. On the other hand, CSR can be just PR (public relations) trick, it is subjective and impossible to measure and it can increase costs (compliance costs — costs of being ethical, that we talked about in 1.2).

Look back at class objectives. Do you feel you can do these things?

— Distinguish mission and vision statement (AO2)

— Analyse common business objectives: growth, profit,

shareholder value, ethical objectives (AO2)

— Discuss strategic and tactical objectives (AO3)

— Examine corporate social responsibility (CSR) (AO3)

Make sure you can define all of these:

1. Vision statement

2. Mission statement

3. Goal

4. Objective

5. Strategy

6. Tactic

7. GOST

8. Strategic level

9. Tactical level

10. Operational level

11. Senior management

12. Middle management

13. Junior management

14. Generic strategy

15. Corporate strategy

16. Operational strategy

17. Profit

18. Growth

19. Shareholder value

20. Ethical objectives

21. Strategic objectives

22. Tactical objectives

23. Operational objectives

24. SMART

25. Corporate social responsibility (CSR)

Check out these resources to boost your BM knowledge and skills:

— boosty.to/lewwinski

— tiktok.com/@lewwinski. business

— youtube.com/@lewwinski

Look for Lewwinski or Lewwinski Business on other social media!

1.4 Stakeholders

Class objectives:

— Distinguish internal and external stakeholders (AO2)

— Discuss stakeholder conflicts (AO2)

The main point of this chapter is to learn a very easy and very important concept.

i. INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL STAKEHOLDERS

Distinguish internal and external stakeholders (AO2)

Stakeholders are people or organisations who affect or are affected by business decisions and/or have an interest (stake) in the operation of a particular business. “Stake” in “stakeholders” does not necessarily refer to a portion of shares in a particular company, that we learnt earlier in chapter 1.2. Here it refers to interest in operations of a particular business. If I had to coin this term, I would call stakeholders “interest-holders”.

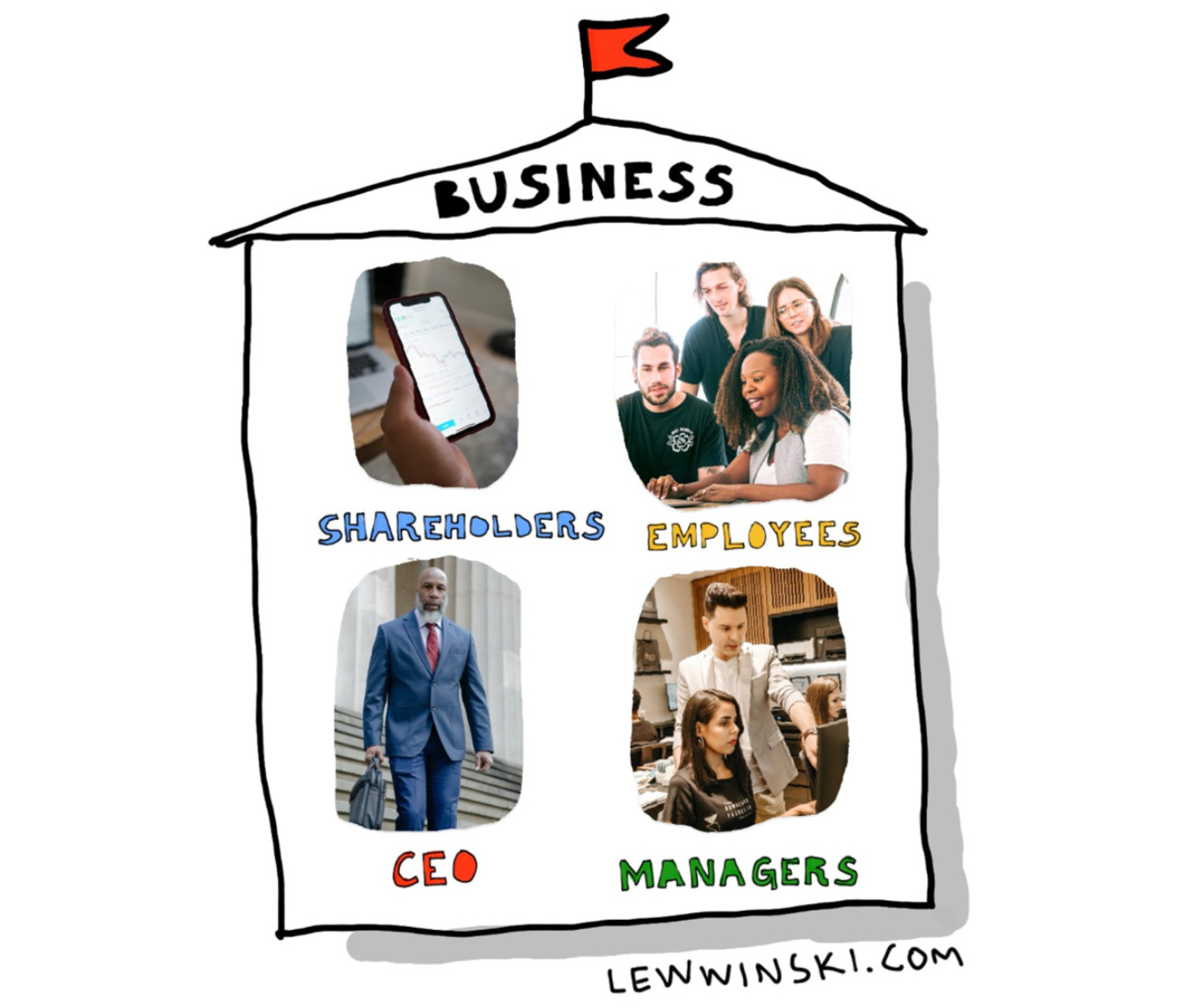

Stakeholders can be internal and external. Internal stakeholders are the ones that are inside the business. Let’s see some examples of internal stakeholders and examples of their common interests and objectives.

— Shareholders usually want to maximise shareholder value (more on that in chapter 1.3).

— Managers usually want to achieve their objectives in the shortest time and at the lowest possible costs.

— Employees usually want good working conditions, meaningful work and maximum pay for minimum effort.

— CEO usually wants to keep shareholders and board of directors (BOD) happy.

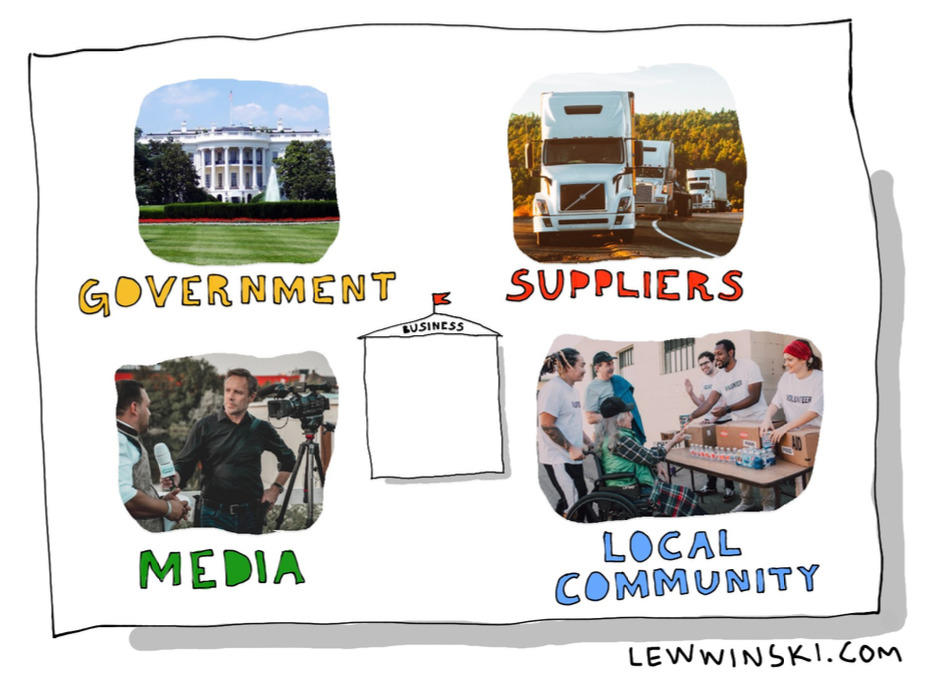

External stakeholders are the ones that are outside the business. Let’s see some examples of external stakeholders and some examples of their common interests and objectives.

— Government usually wants stable tax revenues, compliance with law and voters’ support.

— Media usually wants good stories that readers/viewers will like, regardless of whether the stories are positive or negative.

— Local community wants good employment opportunities in their area and safe environment.

— Suppliers usually want constant orders and short credit period (more about that in Unit 3).

In addition to internal and external stakeholders, there are also some groups that are hard to categorise. For example, there is no agreement whether competitors should be considered stakeholders at all… They are affected by the business, but do they really have an interest in operations of the business they compete with? In addition to that, employees who live in the local community are internal and external at the same time. So, from this perspective, stakeholder, as a business management term, is not entirely clear.

I also have to remind you that stakeholder and shareholder is not the same thing and please beware of spelling. In my experience, some students use these words interchangeably sometimes and it might result in major misunderstanding. Shareholders are stakeholders, but there are also other stakeholders, in addition to shareholders. If it doesn’t make sense, please read this chapter again or talk to your teacher.

ii. STAKEHOLDER CONFLICTS

Discuss stakeholder conflicts (AO2)

As you learnt from the previous section of this chapter, stakeholders have different interests and they might pursue different objectives. Stakeholder conflict happens when there is a clash of stakeholder interests, i.e. when different stakeholder groups want different, sometimes opposite, things. For example, employees usually demand higher wages and lower working hours, but managers demand the exact opposite: a lot of work for little payment.

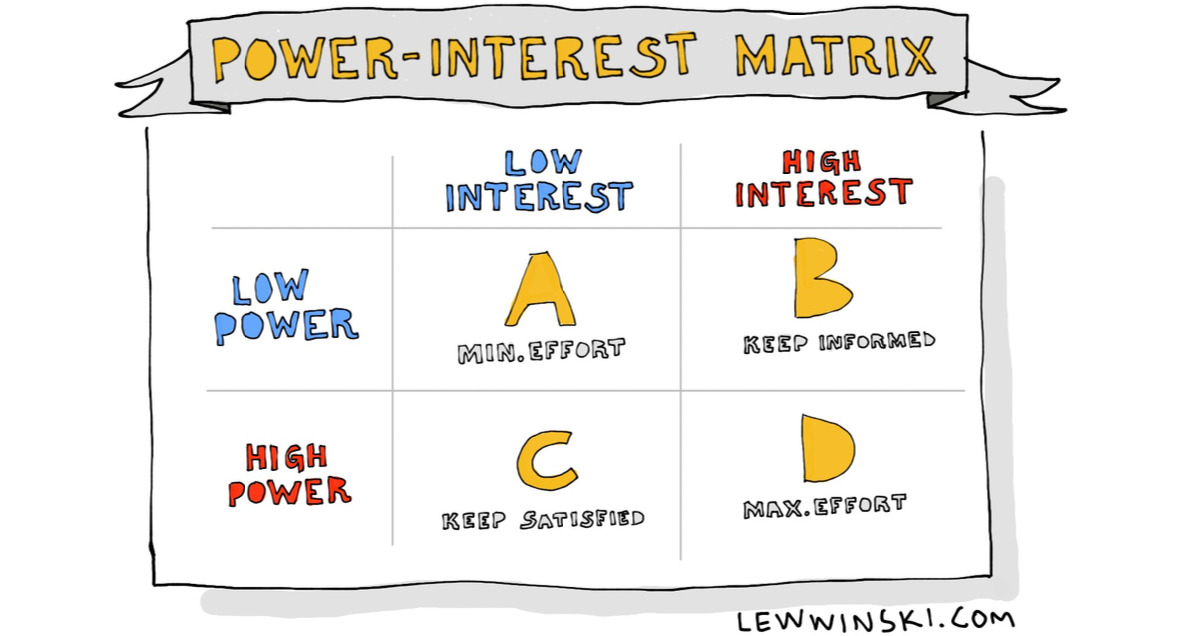

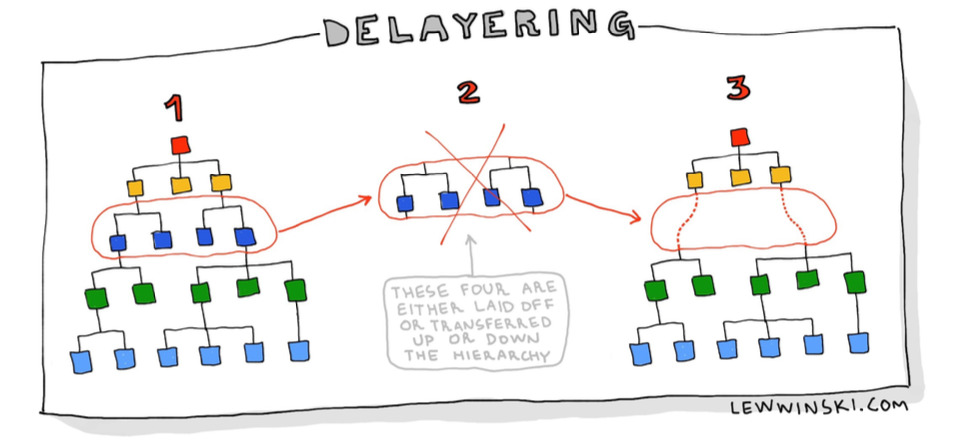

It is important for businesses to keep all stakeholders satisfied and to resolve conflicts. If conflicts occur, there are two visual tools (not included into the Toolkit), that can help managers to resolve stakeholder conflicts: power-interest matrix and stakeholder analysis. Let’s discover each of them in more detail.

Power-interest matrix (or power-interest model, or stakeholder mapping) is a visual tool that helps to break down all stakeholders into 4 groups and prioritise the resolution of conflicts. There are two axes in this matrix — power and interest — hence the name.

Power of decision-making and interest in business can be high and low, which gives us four stakeholder groups.

A. Low interest, low power. This group requires minimum effort. Usually local community is in this group. They don’t really care about businesses as long as there are employment opportunities and the environment is safe.

B. High interest, low power. This group should be kept informed. Usually customers are in this group. They do care a lot about the products but they don’t have much direct influence on business decision-making. Keeping them informed of the business practices and decisions usually prevents stakeholder conflicts.

C. Low interest, high power. This group should be kept satisfied. Usually government is in this group. Individual businesses are not really in their sphere of interest but they do have a lot of power that impacts business decision-making.

D. High interest, high power. This group requires maximum effort. Usually shareholders are in this group. They have direct interest in business and they are the key decision-makers on strategic level.

Please keep in mind that examples that of stakeholders in groups A, B, C, and D that I provided above are examples! It doesn’t mean that it’s always like this. It all depends on a particular conflict. In my class, I usually divide students in groups and let them role-play a stakeholder conflict using power-interest matrix and sign a binding contract by all involved parties in the end.

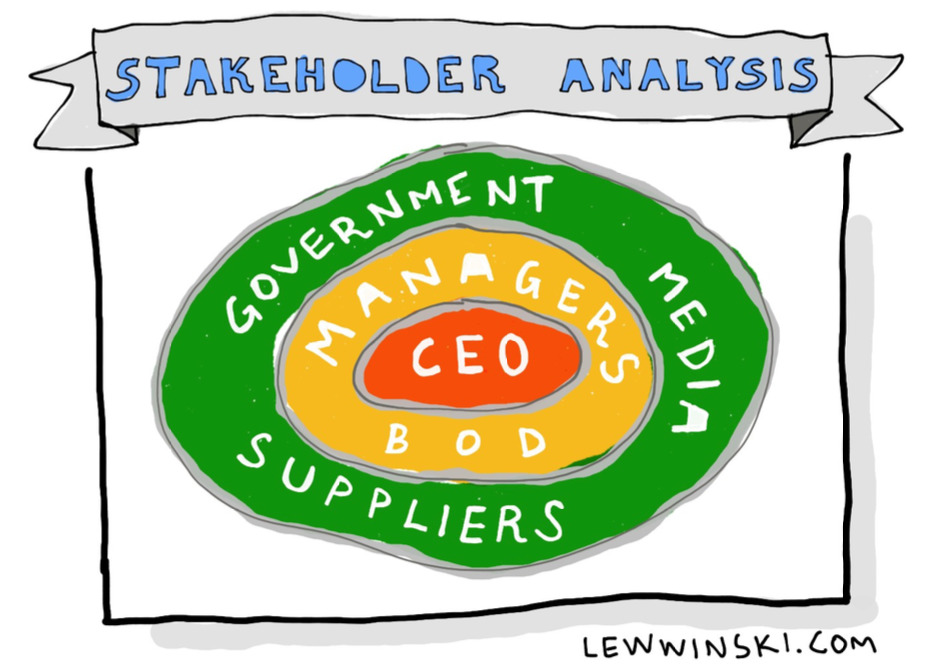

The second visual tool is called stakeholder analysis — a visual representation of the proximity to decision-making in a particular stakeholder conflict.

The main advantage of this tool is that it can help you (manager) see easily who the key decision-makers are. However, this analysis is usually subjective and one analysis cannot be applied to two different conflicts. Again, stakeholder groups that I mentioned in the picture above are just for reference. It doesn’t mean that it’s like this in all stakeholder conflicts.

That’s it. You know who stakeholders are, you know that they can be internal and external, you know what they usually want, you know what causes conflicts between them and you know some ways that can help resolve them.

Look back at class objectives. Do you feel you can do these things?

— Distinguish internal and external stakeholders (AO2)

— Discuss stakeholder conflicts (AO2)

Make sure you can define all of these:

1. Stakeholders

2. Stake

3. Internal stakeholders

4. Shareholders

5. Managers

6. Employees

7. CEO

8. External stakeholders

9. Government

10. Local community

11. Media

12. Suppliers

13. Competitors

14. Stakeholder conflict

15. Power-interest matrix/model (stakeholder mapping)

16. Stakeholder analysis

Check out these resources to boost your BM knowledge and skills:

— boosty.to/lewwinski

— tiktok.com/@lewwinski. business

— youtube.com/@lewwinski

Look for Lewwinski or Lewwinski Business on other social media!

1.5 Growth and evolution

Class objectives:

— Distinguish internal and external economies and diseconomies

of scale (AO2)

— Distinguish internal and external growth (AO2)

— Evaluate the reasons for businesses to grow (AO3)

— Evaluate the reasons for businesses to stay small (AO3)

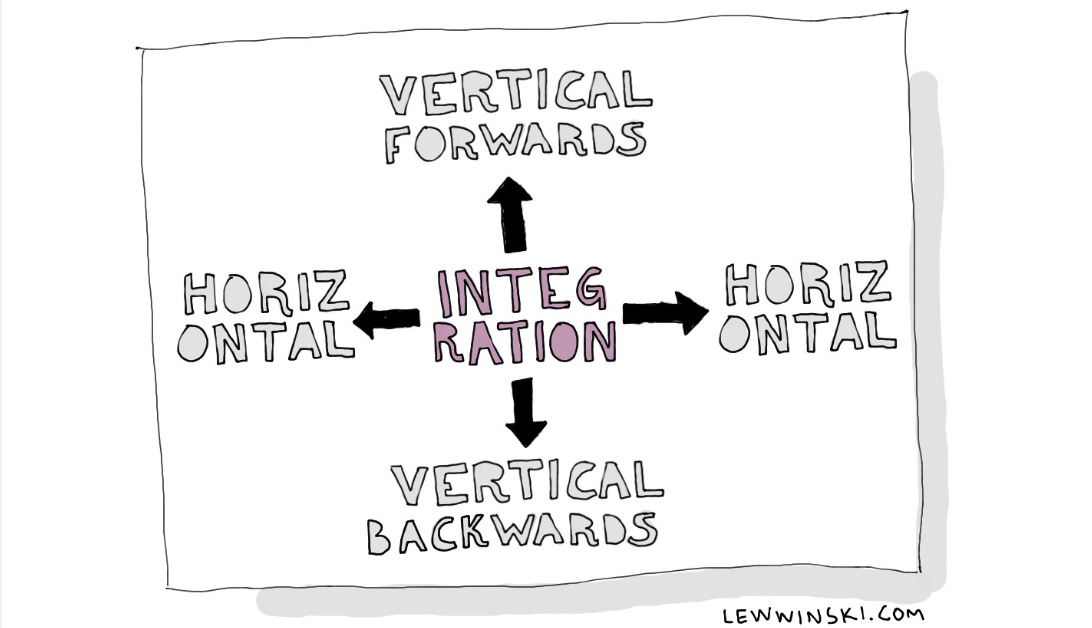

— Compare and contrast external growth methods (AO3)