Бесплатный фрагмент - Food Underfoot

The Cuisine of The Ancient Roads

Introduction

Since ancient times, humans have lived in deep harmony with nature — not merely as observers, but as participants in the great rhythm of life. Long before agriculture, supermarkets, and refrigeration, food did not come wrapped or labelled. It had to be recognised, sought out, gathered, and preserved. On long journeys and nomadic paths, our ancestors carried no provisions. They lived from the land, trusting in what the Earth offered: wild sustenance.

For the ancient traveller, wild plants were not a last resort — they were life itself. Leaves and roots, berries and seeds, mushrooms and shoots were transformed into nourishing meals through knowledge passed down through generations. What modern eyes may dismiss as roadside weeds, they understood as remedy, sustenance, and spice. Forests, meadows, swamps, and mountains were both pantry and pharmacy.

This book is devoted entirely to wild plants — not mushrooms, meat, or fish — each of which is a world of its own and deserves separate attention.

It is an invitation to rekindle our connection with nature’s abundance. Together, we will wander through seasons and landscapes, uncovering forgotten flavours: acorn bread (Quercus spp.), nettle soup (Urtica dioica), rowanberry jam (Sorbus aucuparia), fireweed tea (Chamaenerion angustifolium, syn. Epilobium angustifolium), dandelion-root coffee (Taraxacum officinale), and more.

You will find no recipes here calling for shop-bought flour or potatoes. Instead, you will discover the taste of place: wild ingredients freely available to those willing to step into a meadow or woodland and open themselves to flavours both ancient and new.

To help you navigate, the book is divided into chapters. Feel free to begin wherever your curiosity draws you — be it wild vinegars, herbal milks, plant-based cheeses, or rustic, forest-baked breads — and let your skills grow naturally from there.

This book is for the curious — for those who wish to harvest lightly, cook creatively, and rediscover the quiet joy of belonging. Perhaps one day, with a basket in hand and your feet on a mossy path, you will feel the spirit of an old traveller stirring within you — one who walks with trust, with knowledge, and with gratitude for the gifts underfoot.

About the Author

The author of this edition is a certified biologist (UrSPU, degree in Biology, 1999; RUDN, program “Russian Herbalism,” 2018) who has dedicated many years of her life to the study of folk medicine and herbal traditions.

Chapter 1. Identification and foraging

In this chapter, you will learn how to make vinegars from foraged ingredients — aromatic, healing, and unique. They will enrich your cooking and bring true character to your pantry.

Why plant identification matters

Wild plants are found everywhere: in shaded woods, sunlit meadows, and along quiet trails. They nourish, inspire, and support us. Yet within this abundance are toxic mimics that resemble edible species. A mistake in identification can be harmful — or even deadly. Learning to recognise safe species and distinguish them from their dangerous counterparts is the foundation of responsible foraging.

Poisonous look-alikes: be aware

Vinegar is formed through a two-stage fermentation. First, the sugars contained in the raw material are converted into alcohol by yeasts; then the alcohol is transformed into acetic acid by bacteria (Acetobacter). Here are the main steps of the process:

Here are some examples that highlight the importance of correct identification:

1. Choosing raw materials

A wide range of plants can be used for vinegar fermentation, such as:

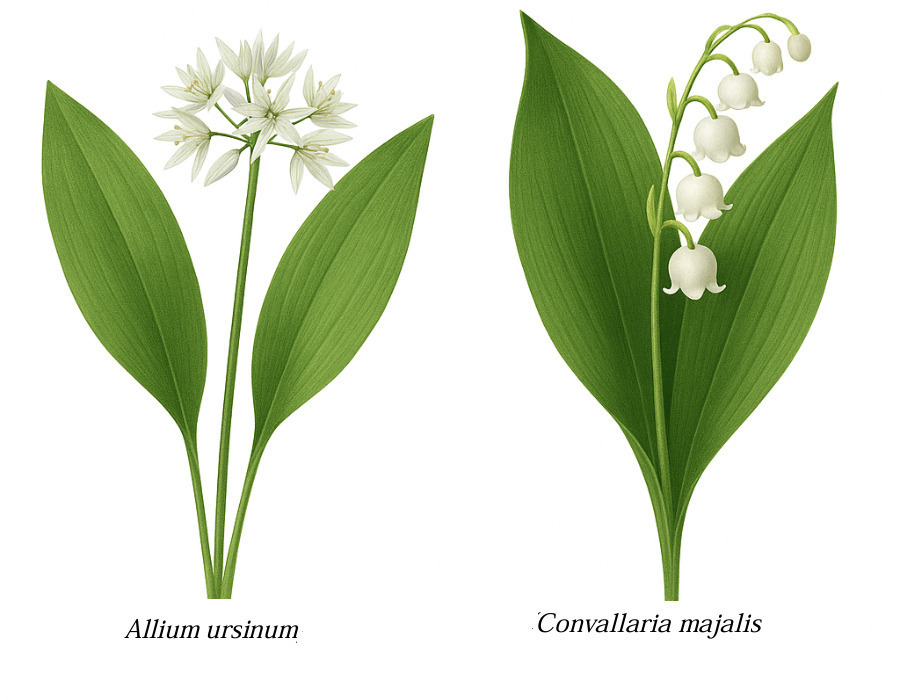

Wild garlic vs. lily of the valley

Wild garlic (Allium ursinum) is prized for its intense aroma and culinary versatility. However, it closely resembles lily of the valley (Convallaria majalis), a highly toxic plant containing convallatoxins in all parts.

It is essential that the plants are fresh, clean, and free from mould or contamination.

2. Fermentation base

To begin fermentation, you will need:

Key difference: wild garlic smells strongly of garlic when crushed; lily of the valley has no such scent.

Tip: Crush a leaf gently — if it smells like garlic, it’s safe. If it’s odourless or smells odd, avoid it.

3. Fermentation process

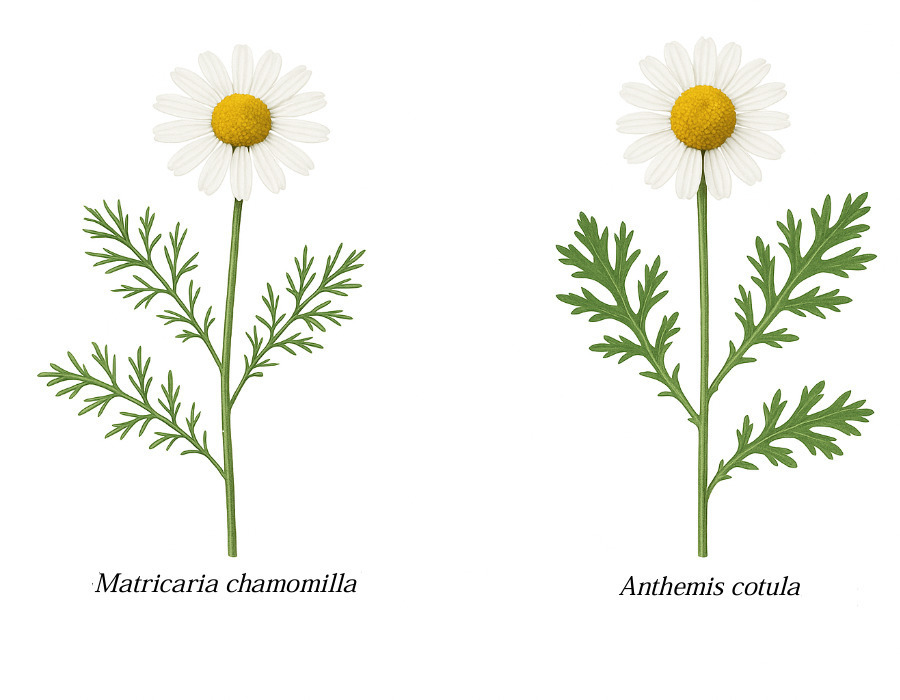

Chamomile vs. stinking chamomile

4. Fermentation conditions

Real chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) has soothing properties and a sweet scent. Its mimic (Anthemis cotula) has a sharp, unpleasant odour and can cause allergies. The base of Matricaria’s flower head is hollow, whereas that of Anthemis is solid.

To help you navigate, the book is divided into chapters. Feel free to begin wherever your curiosity draws you — be it wild vinegars, herbal milks, plant-based cheeses, or rustic, forest-baked breads — and let your skills grow naturally from there.

5. Filtering

Once fermentation is complete (when the vinegar has become sufficiently sharp), strain the liquid through muslin or a sieve to remove plant residues. Decant into sterilised bottles or jars for storage.

Tip: Slice the flower head — if it’s hollow, it’s true chamomile. If solid and smelly, it’s the stinking kind.

Cabbage thistle vs. creeping thistle

Cabbage thistle (Cirsium oleraceum) is one of the softest and most palatable representatives of its genus, with pale green leaves lacking strong spines and light yellow flowers. Its young shoots and leaves are tender and suitable for cooking or stewing. Creeping thistle (Cirsium arvense), by contrast, is tougher, with pronounced spines on the leaves and purple flowers. Its roots can sometimes be used after processing, but the aerial parts are too fibrous and bitter.

Tip: Pay attention to flower colour and leaf texture. Cabbage thistle has soft, wide leaves with a slightly wavy edge and almost no spines. Creeping thistle has narrow, stiff leaves with sharp spines, and bright pink to purple flowers. Cabbage thistle prefers moist, shady places like damp meadows and ravines, while creeping thistle thrives in dry, sunny fields.

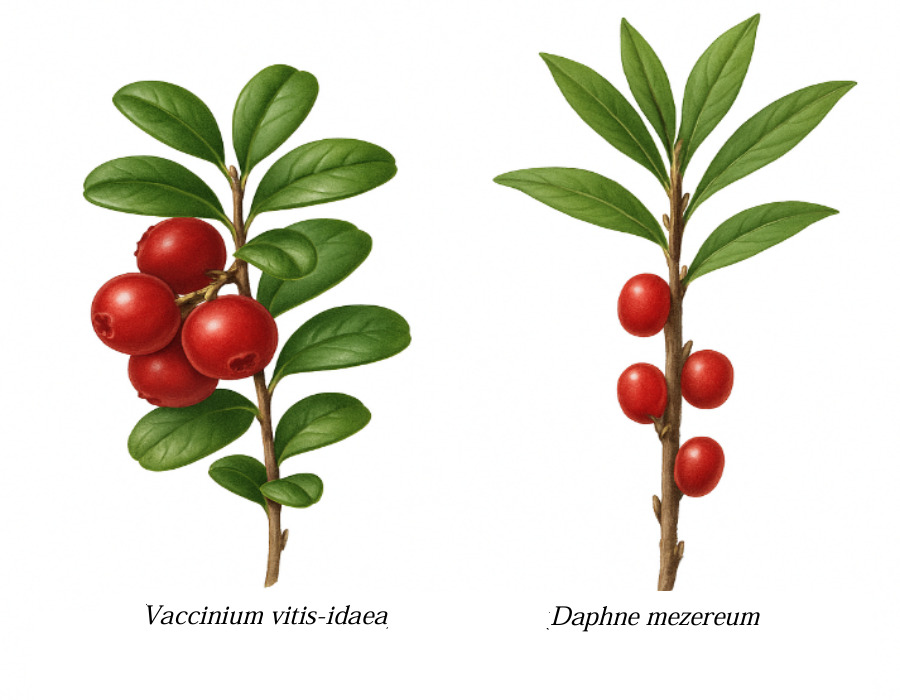

Lingonberry vs. mezereum / spurge laurel

Lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) is a low-growing evergreen shrub with small, leathery dark green leaves and bright red berries. The berries are sweet and tart, used fresh or in jams, compotes, and juices. Common daphne (Daphne mezereum) is a deciduous shrub up to 1 metre tall. Its leaves fall off before flowering, so in spring it appears as a bare bush with clusters of bright pink flowers, followed by shiny red berries. All parts of this plant are poisonous, especially the bark and berries, which may cause vomiting, convulsions, and coma if ingested.

Tip: Lingonberry leaves remain through winter, and berries grow in the axils of the lower leaves. The skin is thick and slightly matte. Daphne berries grow on bare branches without leaves, are shiny, and very soft.

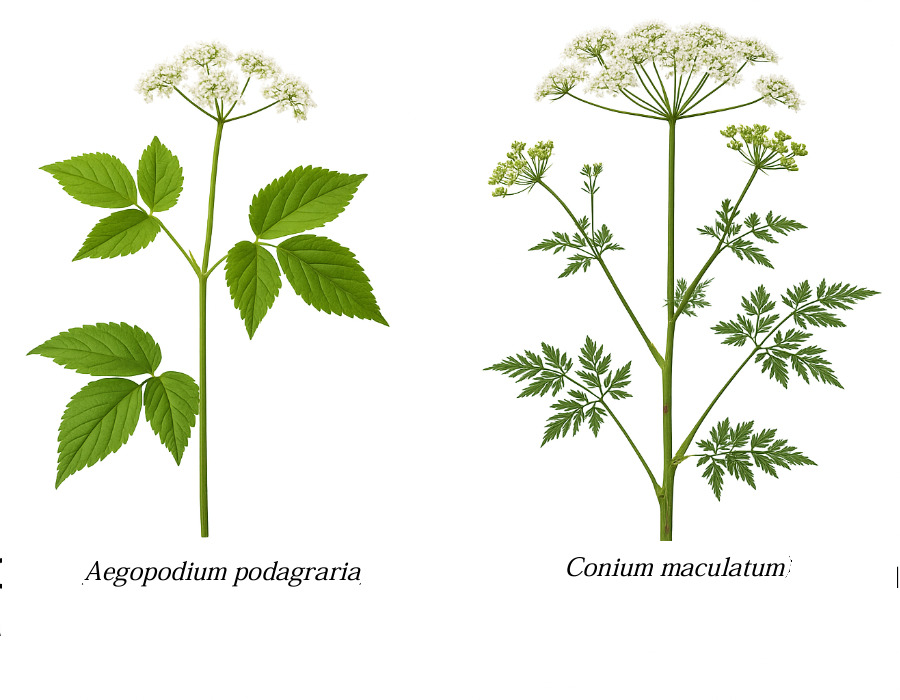

Ground elder vs. poison hemlock

Ground elder (Aegopodium podagraria) is a tasty, edible plant with delicate leaves, excellent for salads and soups. It can be mistaken for toxic members of the Apiaceae family, especially poison hemlock (Conium maculatum). One clear distinction is smell: ground elder has a fresh, herbaceous aroma, while hemlock smells foul and “mousy”. Another clue is the leaf stalk: in ground elder, the petiole wraps around the stem in a sheath.

Tip: Ground elder has “crow’s foot” leaf shapes with triple divisions and a sheath at the petiole base. Hemlock has purplish spots on a smooth, bluish stem and an unpleasant rodent-like smell. Never harvest a plant if the stem shows purple blotches.

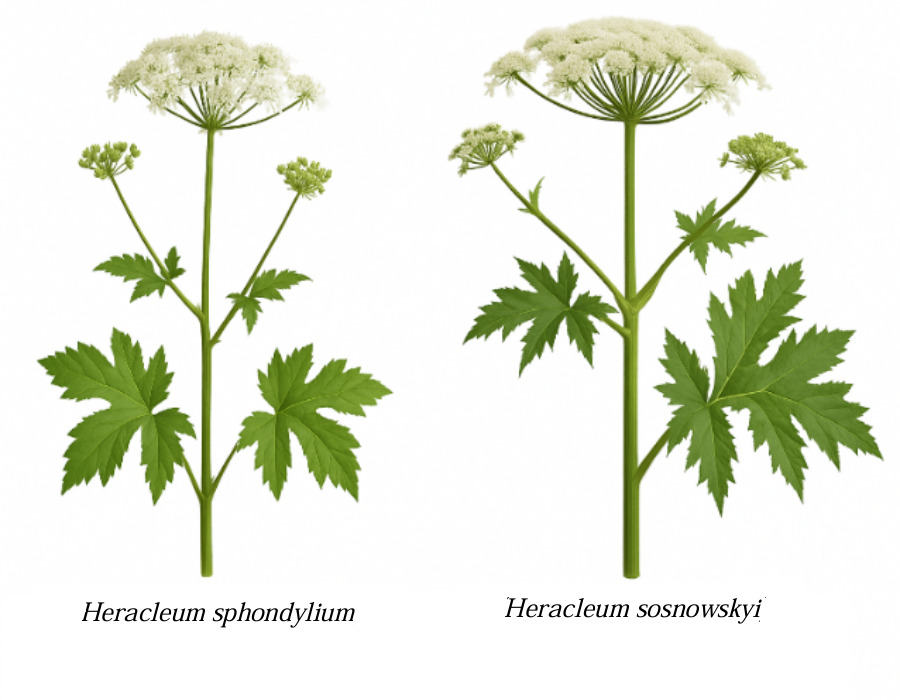

Common hogweed vs. Sosnowsky’s hogweed

Common hogweed (Heracleum sphondylium) is a wild plant long used in folk cuisine. Young leaves and stems are edible raw, pickled, or boiled and used in soups and stews. It reaches about 1.5 metres, has softly hairy stems, large triple-lobed leaves, and white to pinkish umbrella-shaped inflorescences. Though its sap can cause mild skin reactions in hot weather, it’s far less toxic than invasive species. Sosnowsky’s hogweed (Heracleum sosnowskyi), by contrast, is an introduced invasive that grows up to 3–4 metres, with thick stems covered in purple spots, deeply dissected leaves, and enormous white flower heads up to 80 cm wide. Its sap is extremely caustic and can cause severe burns, especially in children.

Tip: Common hogweed has rounded leaves, a softer stem, weak herbaceous smell, and rarely exceeds 1.5 metres in height. Sosnowsky’s hogweed is much larger, smells acrid, has narrow coarse leaves and releases abundant caustic sap when damaged. If unsure, avoid contact entirely.

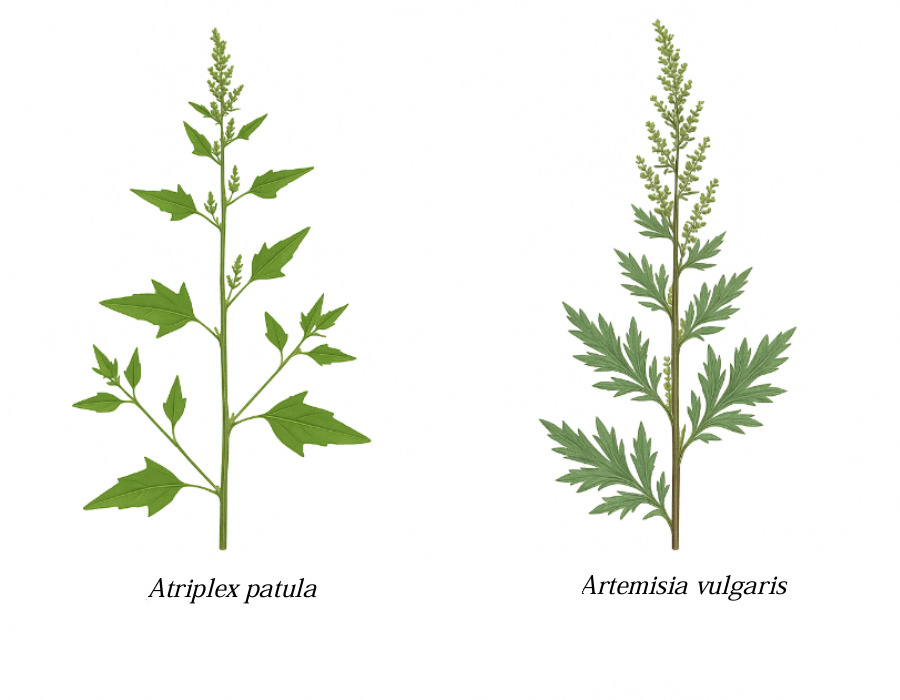

Spear-leaved orache vs. common mugwort

Spear-leaved orache (Atriplex patula) is one of the most widespread edible wild plants from the amaranth family. Its young leaves and shoots can be eaten raw or boiled, with a taste similar to spinach. It’s especially good before flowering. The leaves are triangular to diamond-shaped with a whitish coating, and it grows up to 70 cm tall, often found on disturbed ground and roadsides. Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) is a bitter, aromatic plant from the aster family. Its leaves are fragrant, deeply cut, and silvery underneath. Though edible in very small amounts as a seasoning or medicine, it contains strong essential oils and is unsuitable for regular consumption.

Tip: A. patula has soft, bluish-coated leaves with a mild, non-bitter taste. A. vulgaris has narrow, dissected leaves with a sharp bitter flavour and a strong herbal aroma. Only young orache is edible; mugwort should be used with caution and never in large quantities, especially when collecting seeds for flour.

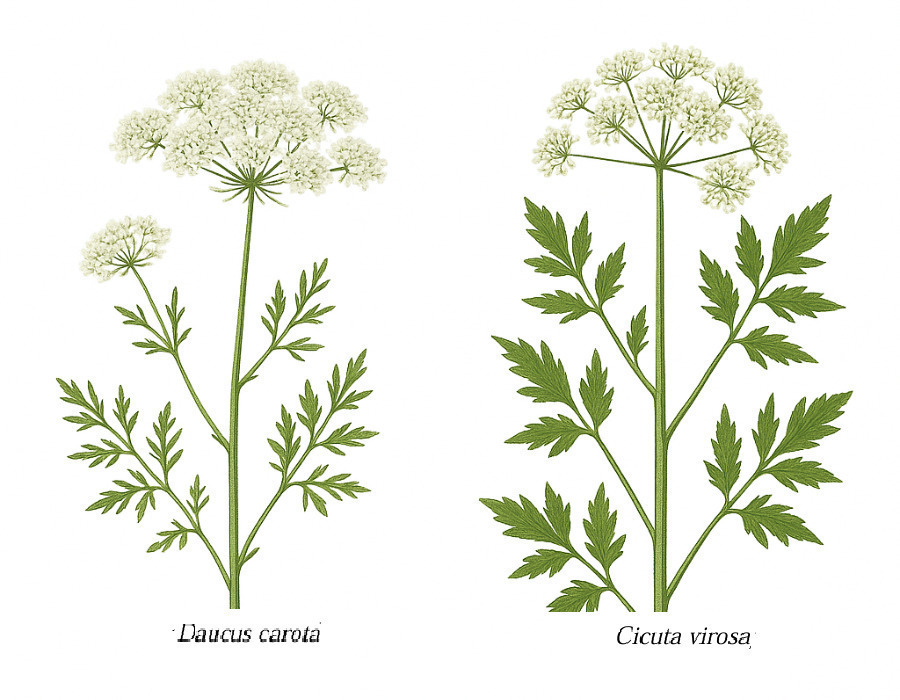

Wild carrot (Daucus carota) vs. water hemlock (Cicuta virosa)

Wild carrot has an edible root and delicate, lace-like flower clusters. However, it closely resembles water hemlock, one of the most toxic plants in temperate climates. The key differences lie in the smell and root shape: wild carrot smells pleasantly carroty, while water hemlock has an unpleasant mouse-like odour and a hollow, mottled root.

Tip: Rub the root: wild carrot smells sweet and familiar, while hemlock is repulsive. Also, wild carrot often has a small dark spot (“pseudo-flower”) in the centre of the umbel — absent in water hemlock.

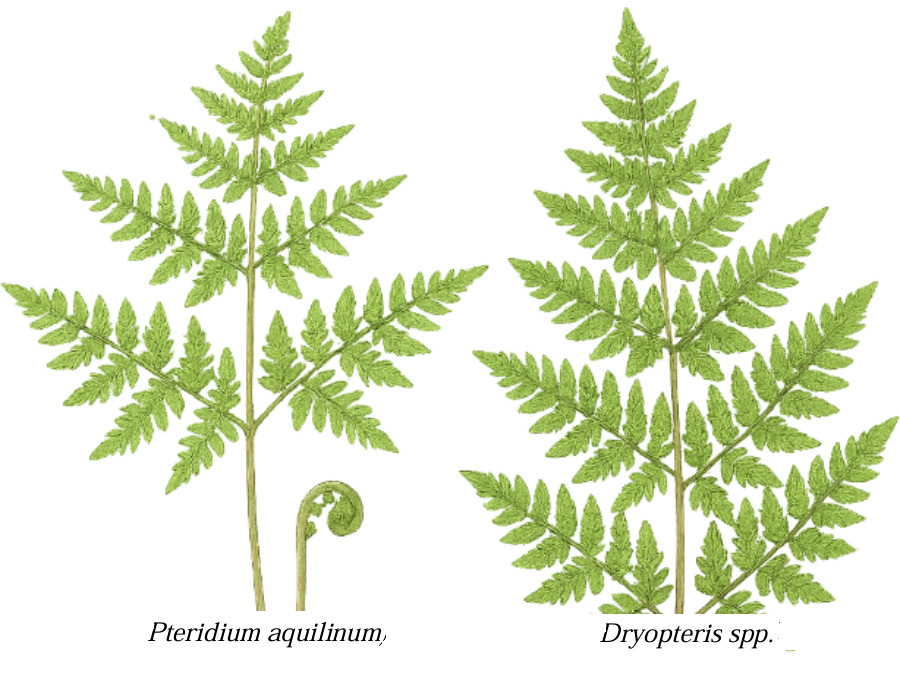

Bracken fern vs. male fern

Young shoots, ‘fiddleheads’, of bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) can be eaten after proper cooking in some traditional cuisines, but now many health authorities, including the WHO and FDA, advise against its consumption — even when cooked — because it contains ptaquiloside, a carcinogenic compound. Mature parts and similar species are toxic. Bracken has smooth stalks and triangular fronds; male ferns (Dryopteris spp.) tend to be denser and feature brown scales at the base.

Tip: Bracken fiddleheads are smooth and smell like fresh grass. Dryopteris shoots are hairy, clustered, and musty.

Plant identification techniques

These examples show: visual similarity alone is never sufficient. Pay attention to smell, texture, leaf shape, and habitat when identifying any plant.

Identification techniques

The ability to recognise wild plants develops with time and practice. There are several helpful methods, each suited to different situations and levels of experience:

Field guides

Field guides are compact books or leaflets containing descriptions, illustrations, and photographs of plants. They are indispensable in the field because they do not require internet access. A good field guide should include:

— A detailed description of external features: leaf shape, stem colour, type of inflorescence.

— Information about habitat and seasonal characteristics.

— Comparisons with similar species, including poisonous look-alikes.

For beginners, guides with vivid colour illustrations are ideal. More experienced foragers may prefer botanical references with scientific classifications. It is advisable to consult several sources to reflect the diversity of local flora and seasonal variation.

Consultation with experienced foragers

There is no substitute for hands-on learning. Studying with experienced foragers is highly valuable. They can show you plants in their natural environment, explain key identification features, share regional knowledge, and help you avoid common mistakes.

Consider the following:

— Join local ecological or botanical clubs.

— Participate in forums or social media groups focused on wild flora.

— Attend plant identification walks, excursions, or workshops.

Self-study

If you prefer to explore the world of wild plants independently, start with a simple approach:

— Choose 3–5 well-known and easily recognisable species, such as:

— Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica)

— Common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

— Broadleaf plantain (Plantago major)

— Wild garlic (Allium ursinum)

— Study their appearance, characteristics, and seasonal growth using both books and online resources.

— Take nature walks, observe the selected plants, and compare them with your research.

— Gradually expand your list, reinforcing your knowledge through repeated practice.

This method requires patience but leads to a deep understanding of your local flora and greater confidence in identifying safe species.

Resources for self-study

Online Botanical Databases and Guides

Herbarium.live — Digital Herbarium

— A collection of high-quality herbarium specimens with detailed scientific descriptions.

Useful for plant identification, comparison with herbarium standards, and study.

GBIF — Global Biodiversity Information Facility

— A global database of biodiversity observations.

Includes species distribution, range maps, publications, data export, and records.

The Plant List

— A comprehensive taxonomic database of the world’s plants.

Allows searches by Latin names, synonyms, and authors of plant descriptions.

Plants of the World Online (Kew Gardens)

— An authoritative resource from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Global plant data, distribution, ecology, and taxonomy.

Interactive maps and floristic atlases

eFloras.org (including Flora of China, North America, etc.)

— Offers detailed botanical descriptions and identification keys.

Especially useful for studying regional flora.

BIN RAS Distribution Maps (GBIN — Russian Academy of Sciences)

— Specialized academic-level resources on the flora and fauna of Russia.

Range maps and scientific data.

Mobile applications (with photo recognition)

PlantNet

— A free, crowdsourced plant identification app.

Good botanical accuracy; data can be exported to GBIF.

iNaturalist

— A project by the California Academy of Sciences and National Geographic.

Photo recognition with verification by the scientific community; data export supported.

Seek by iNaturalist

— A simplified version of iNaturalist, designed for kids and beginners.

No registration required; works offline.

Flora Incognita

— A highly accurate European app developed by the Technical University of Ilmenau.

Scientific descriptions, conservation status, and common European plants.

PictureThis

— A commercial app with a free trial period.

Offers plant recognition, brief descriptions, and care tips.

Foraging safety principles

Responsible wild plant gathering is not only about finding food or medicine — it’s also about honouring and protecting the natural world. Follow these key principles to stay safe and harvest sustainably.

Choosing the right time and place

— Time of collection: The best time to gather is in the morning — plants are fresh, vibrant, and rich in nutrients. By afternoon, especially during heat, they may wilt or lose some beneficial properties. After rain, many plants spoil more quickly.

— Where to pick: Choose clean, unpolluted areas far from roads, industrial zones, or fields treated with pesticides. Forests, meadows, nature reserves, and national parks (where foraging is allowed) are good choices.

Tools for safe and sustainable foraging

Using the right tools makes harvesting safer and more efficient:

— Scissors or secateurs: Sharp tools allow you to collect cleanly, reducing damage and preserving plant roots.

— Baskets or cotton bags: Breathable containers prevent overheating and moisture buildup, keeping your harvest fresh.

— Gloves: Important for protecting your hands from nettles, thorns, or irritating sap.

Practising ecological foraging

Harvest in ways that allow nature to regenerate:

— Don’t uproot entire plants: Take only what you need — leaves, flowers, or seeds — and leave the roots intact whenever possible.

— Harvest in moderation: Avoid taking more than 10–20% of any plant species in one area to maintain healthy populations.

— Respect rare species: Learn to identify protected or endangered plants and avoid harvesting them altogether.

Seasonality of harvesting

Nature lives in cycles, and each season brings its own gifts:

Spring

A time of awakening: young leaves and shoots of nettle, dandelion, ground elder, and plantain are especially rich in nutrients. Edible flowers like violet, primrose, and wild garlic are valuable for fresh use, teas, and tinctures.

Summer

Nature flourishes with blossoms and ripening berries. Gather elderflower, linden, and chamomile for infusions, and fruits like raspberries, blackberries, rose hips, and blueberries for jams and drying.

Autumn

The season of gathering and storing. Roots such as burdock, couch grass, and dandelion are harvested now, along with nuts and seeds like hazelnuts, acorns, and edible chestnuts. Late berries like viburnum and rowan are rich in vitamins.

Winter

Even in winter, nature offers gifts. Pine, spruce, or cedar needles make vitamin-rich teas. Birch or willow bark can be used for decoctions. If the ground isn’t frozen, you can carefully dig burdock or chicory roots.

Regional characteristics

Every landscape shapes its local flora:

— Forests: Provide nettles, wild garlic, fern shoots, and berries like raspberries, blackberries, blueberries, and lingonberries. Mushrooms may also be present — harvest only if you’re confident in your knowledge.

— Steppes: Rich in herbs like amaranth, wild sorrel, ragwort, chamomile, wormwood, and yarrow.

— Bogs and wetlands: Offer cranberries, cloudberries, and specialized herbs like Labrador tea (Ledum), which should be handled with care due to toxicity.

— Mountains: Host rare and protected plants such as Rhodiola rosea or edelweiss (not to be harvested). Edible alpine plants include raspberries, blueberries, and sea buckthorn.

Tips for beginners

If you’re just starting to explore wild plants, keep these recommendations in mind:

— Start simple: Learn a few common and easy-to-identify species first.

— Keep a journal: Record harvest locations, dates, and conditions to build your own foraging guide.

— Be cautious: If you’re unsure about a plant, leave it. Safety comes first.

— Observe nature: Spend time outdoors watching how plants grow, change, and respond to the seasons.

— Exchange seeds: Trade seeds of rare edible wild plants to grow at home.

— Share knowledge: Contribute your discoveries and recipes through blogs or community groups.

— Build community: Organise local workshops, walks, or wild food festivals.

— Enjoy the process: Let plant gathering be not just a practical skill but a way to connect deeply with the natural world.

FINAL NOTE

Identifying and harvesting wild plants is an art that blends knowledge, mindfulness, and deep respect for the living world. By following the principles in this chapter, you’ll not only gather safely but also turn your finds into nourishing meals and healing remedies.

In the chapters ahead, we’ll continue this journey along ancient trails — turning foraging into a culinary adventure that revives ancestral wisdom and awakens forgotten flavours.

Chapter 2. Preparing wild plants for use

Before nature’s gifts can be turned into wholesome meals or healing remedies, they must first be properly prepared. This essential process not only ensures safe consumption but also enhances flavour and preserves the nutritional richness of wild plants.

This chapter will guide you through the steps for cleaning, drying, storing, and processing your harvest, along with the tools and equipment you’ll need. Once you master these techniques, you’ll be able to transform nature’s abundance into true culinary treasures.

The importance of preparation

Wild plants gathered from forests, meadows, or riverbanks often bear traces of the environment — dust, insects, or traces of animals. Some may also contain natural toxins or bitter compounds that must be removed before consumption.

Proper preparation ensures safety, improves taste, and helps retain nutritional value. Whether you plan to use your harvest fresh or store it for later, preparation is a vital first step.

Cleaning and washing

Cleaning is the foundation of wild plant preparation. The method depends on the type of material — leaves, roots, fruits, or flowers — each requires specific handling.

Leaves and herbs

— Tender leaves (e.g., Urtica dioica — stinging nettle), Aegopodium podagraria — ground elder, Taraxacum officinale — dandelion): Rinse gently in cool water to remove dust and insects. For deeper cleaning, soak in cold water for 5–10 minutes, then rinse under running water.

— Tougher leaves (e.g., Plantago major — plantain): May be waxy or retain more soil. Use a soft brush or sponge to scrub gently under running water.

Tip: Wear gloves when handling stinging or prickly plants such as nettles — this will protect your hands and make preparation easier.

Roots and rhizomes

— Roots (e.g., Arctium lappa (greater burdock), Cichorium intybus (chicory), Taraxacum officinale (dandelion)): Rinse thoroughly under running water. Use a stiff-bristled brush or fine scourer to scrub away dirt. Cut larger roots into pieces for easier cleaning.

Tip: Soak especially dirty roots in cold water for 15–20 minutes before scrubbing.

Fruits and berries

— Berries (e.g., Rosa canina (rose hips), Vaccinium corymbosum (blueberries), Rubus idaeus (raspberries)): Rinse gently under a gentle flow of water. To remove insects, soak in lightly salted water (1 tsp salt per litre) for 10 minutes, then rinse again.

— Hard-skinned fruits (e.g., Quercus robur (oak acorns), Castanea sativa (sweet chestnuts)): Rinse under running water and use a brush if necessary.

Flowers

— Flowers (e.g., Sambucus nigra (elderflower), Tilia cordata (lime), Taraxacum officinale (dandelion)): Gently shake to dislodge any dust or insects. Rinse briefly under a light stream of water; avoid soaking, as flowers lose their aroma.

Tip: Drain in a colander or blot on kitchen paper. Gently pat leaves and herbs dry with a paper towel to remove excess moisture.

Drying

Drying is one of the oldest preservation methods. Properly dried plants retain much of their flavour, aroma, and nutritional value and can be used in teas, seasonings, powders, or tinctures.

Drying methods

Choose your method based on the plant type and your available equipment.

Air drying

— Leaves and herbs: Spread in a single layer on cloth or mesh in a dark, well-ventilated place. Avoid sunlight. Turn every 1 to 2 days. Drying takes 3 to 7 days.

— Flowers: Tie into small bundles and hang upside down in a dry, dark room for 5 to 10 days.

Tip: Cover with gauze or mesh to protect from insects.

Oven drying

— Roots and thick leaves: Slice thinly and spread on a parchment-lined tray. Set the oven to 50–60°C with the door slightly open. Drying takes 2–4 hours.

Tip: Check at regular intervals (e.g. every 30 minutes) to avoid overdrying or scorching.

Dehydrator drying

— Suitable for all types of plants.

— Set to 35–40°C for herbs and flowers, 50–60°C for roots and fruits. Drying time: 4–12 hours.

Tip: Dehydrators preserve more nutrients and allow precise control.

Signs of proper drying

— Leaves and herbs: Crumble easily.

— Roots: Become hard and brittle.

— Fruits and berries: Should be dry with no internal moisture. Berries may stay slightly pliable; nuts should be firm and dry.

Storage

Proper storage keeps dried plants fresh, fragrant, and effective for months or even years.

Storage recommendations

— Herbs and leaves should be kept in glass jars with airtight lids or paper bags. Avoid plastic.

— Roots and seeds: Use glass or ceramic containers with secure lids.

— Fruits and berries: Best in cloth bags or glass jars.

General Tips

— Store in a cool, dark, dry place, away from direct sunlight or heat.

— Label containers with plant name and harvest year.

— Check regularly for mould or pests, and discard any spoiled material.

Shelf life

— Leaves and herbs: up to 1 year

— Roots and seeds: up to 2 years

— Fruits and berries: up to 1 year

Main processing methods

Besides drying, methods like fermentation and pickling help preserve wild plants while enriching their flavour.

Fermentation

Fermentation transforms plant sugars into beneficial acids and flavours. It preserves and enhances nutrients.

Basic fermented greens recipe

Ingredients:

— 500 g fresh leaves (e.g., Urtica dioica (nettle), Aegopodium podagraria (ground elder), Taraxacum officinale (dandelion))

— 1 tbsp salt

— Water

Preparation:

— Wash and coarsely chop the leaves.

— Pack tightly into a clean glass jar.

— Dissolve salt in water and pour over leaves until fully submerged.

— Cover with gauze and leave at room temperature for 3 to 5 days.

— After fermenting, seal with a lid and refrigerate.

Use: in salads, soups, or as a tangy side.

Pickling

Pickling preserves plants in a vinegar-based brine. Ideal for shoots, roots, and some flowers.

Simple pickled wild garlic recipe

Ingredients:

— 200 g wild garlic shoots (Allium ursinum)

— 200 ml water

— 100 ml apple cider vinegar

— 1 tsp salt

— 1 tsp sugar syrup (or sugar)

Preparation:

— Wash and cut the shoots into 5–7 cm pieces.

— Boil the water with salt, sugar, and vinegar.

— Pack the wild garlic into a sterilised jar and pour the hot liquid over it.

— Allow to cool, seal, and refrigerate.

A tangy addition to salads or savoury snacks.

Tools and equipment

You’ll need some basic kitchen items and, optionally, tools for handling larger batches.

Basic Tools:

— Knives: Sharp ones for cutting leaves, roots, and fruit.

— Cutting boards: Use separate boards for different ingredients to avoid cross-contamination.

— Colanders and sieves: For washing and draining plant materials.

— Containers: Glass jars, cloth bags, or paper bags for storing dried or prepared plants.

— Gloves: Useful when handling irritants or prickly plants such as Urtica dioica (stinging nettle).

Optional equipment:

— Dehydrator: Speeds up drying and allows more control over temperature.

— Fermentation jars: Preferably glass or ceramic with airlock lids.

— Grinder or blender: For making powders or pastes from dried plant material.

Tip: No dehydrator? Use a low-temperature oven or air-dry carefully in a well-ventilated, shaded place.

FINAL NOTE

Preparing wild plants is an art that blends knowledge, patience, and creativity. By mastering the methods of cleaning, drying, storing, and processing, you’ll preserve nature’s gifts and unlock their flavours.

In the next chapters, we’ll explore how these prepared ingredients can be used to create nourishing, original, and deeply connected dishes — a culinary journey along the ancient paths of flavour.

Chapter 3. Bread and baking from wild plants

Return to the roots

Baking bread and other flour-based foods using wild plants is a meaningful way to reconnect with ancestral culinary traditions. By making flour from roots, seeds, and stems, you can create nutritious, aromatic, and unique foods that enrich your table and deepen your connection to the land.

In ancient times, people didn’t always have access to wheat or rye. But that didn’t stop them from baking bread. They used what nature offered: burdock roots, acorns, nettle seeds, goosefoot, and more. These ingredients are rich in fibre, vitamins, and minerals, and they lend distinct flavours and textures to baked goods. Today, as more people pursue natural and sustainable living, baking with wild plants becomes not just an experiment but a way to enrich the diet with wholesome, unprocessed foods.

Preparing flour from wild plants

Flour from roots

Cattail rhizomes (Typha latifolia)

— Harvest: Early spring, when starch content is highest.

— Preparation: Carefully dig up rhizomes (they’re fragile), rinse thoroughly to remove silt. Slice thinly (2–3 mm), let air-dry briefly to eliminate surface moisture, then dry in the shade or oven at ≤ 50°C.

— Grinding: Once fully dried (they should be hard and brittle), grind into fine powder using a coffee grinder or mill.

— Use: Produces a dense, slightly sticky flour with a neutral flavour; ideal for flatbreads, thickening porridge, or mixing into dough.

Sweet flag roots (Acorus calamus)

— Harvest: Autumn (late September to October), after leaves wither.

— Preparation: Dig, wash, and slice roots thinly. Dry in a shaded, ventilated space or at 40–45°C.

— Grinding: Grind to powder.

— Use: Adds spicy-bitter flavour; use in small amounts (5–10%) in gingerbread, cakes, or biscuits.

Dandelion roots (Taraxacum officinale)

— Harvest: Late September to early October.

— Preparation: Wash, trim off thin lateral roots, slice (3–5 mm), air-dry 1 to 2 days, then oven-dry at 40–50°C until crisp.

— Grinding: Grind to powder.

— Use: Slightly bitter, coffee-like taste; dark brown colour; rich in fibre. Add to baked goods (≤ 10%) or use as a thickener.

Burdock roots (Arctium lappa)

— Harvest: Autumn or early spring.

— Preparation: Peel and slice (2–3 mm), dry in shade or at ≤ 50°C.

— Grinding: Grind to powder.

— Use: naturally sweet flavour due to its inulin content; good for bread, flatbreads, and pastries.

Couch grass roots (Elymus repens)

— Harvest: Late summer (August to early September).

— Preparation: Clean, cut, and dry in direct sunlight in warm, dry conditions, or use an oven at 50–60°C”.

— Grinding: Grind to powder.

— Use: Starchy and dense; good as a thickener or mixed with other flours (up to 30–40%).

Common reed rhizomes (Phragmites australis)

— Harvest: Early spring (March — April).

— Preparation: Dig, wash, cut lengthwise to remove tough fibres, slice thinly. Air-dry, then dry in shade or oven at ≤ 50°C.

— Grinding: Grind when brittle.

— Use: High in amylopectin; neutral flavour with mild sweetness. Good for baking and thickening.

Marshmallow roots (Althaea officinalis)

— Harvest: Late autumn (October — November).

— Preparation: Dig, peel, wash, slice (3–4 mm), dry at 40–45°C until brittle.

— Grinding: Grind to powder.

— Use: High in mucilage and starch; creates a light, “puffy” texture; usually mixed with other flours (20–25%).

Liquorice roots (Glycyrrhiza glabra)

— Harvest: Autumn or early spring.

— Preparation: Wash, remove lateral roots, slice thinly, dry in shade or at 45–50°C.

— Grinding: Grind to powder.

— Use: Naturally sweet with a mild liquorice taste; flavouring for biscuits, sweets, or cakes. Use sparingly (≤ 10%).

Leuzea roots (Leuzea carthamoides)

— Harvest: Autumn (September — October).

— Preparation: Dig, clean, slice thinly, dry in shade or ≤ 45°C.

— Grinding: Grind to fine powder.

— Use: Slight bitterness, dense flavour. Use as a minor additive (5–15%) to enrich bread with “medicinal” qualities.

Jerusalem artichoke tubers (Helianthus tuberosus)

— Harvest: Late autumn (October — November), after first frost.

— Preparation: Wash, slice (3–4 mm), let air-dry, then dry in oven at 50°C until brittle.

— Grinding: Grind to fine powder.

— Use: High in inulin, sweet taste. Suitable for diabetic-friendly baking or as a flour substitute (20–30%).

Each root and rhizome must be thoroughly dried before grinding to avoid spoilage. For best quality, grind just before baking. Store flour in airtight containers in a cool, dry place.

Wild root flours can be combined with conventional ones. Always consider the aftertaste and texture: root flours are typically used at 10–30% of total flour weight, depending on the desired effect.

Seed flour

Nettle seeds (Urtica dioica)

— Harvesting: Ripen in late summer, typically August to early September. Mature seed tassels droop, turn dark green or brown, and crumble when shaken. Harvest on dry days, away from roads and livestock areas.

— Preparation: Hang cut tassels in bunches in a well-ventilated, shaded place for 3 to 5 days. Rub between your hands over a sieve to separate seeds from stems. Optionally dry seeds further at 40–45°C for 1–2 hours.

— Grinding: Use a coffee grinder in short pulses to preserve nutrients. Sift for finer texture.

— Features: Rich in protein, vitamins A and E, iron, and unsaturated fats. Nutty, herbal flavour. Use as an additive (up to 10–15%) in breads, pancakes, porridge, smoothies, and raw bars. Store in a tightly sealed jar in a cool, dark place.

Orache seeds (Atriplex patula)

— Harvesting: Mature in autumn, usually in September. Seeds turn dark grey or black and fall easily. Cut tassels in dry weather after leaves have wilted.

— Preparation: Spread on paper or cloth in shade for 3 to 5 days. Thresh by rubbing or shaking in a bag. Sieve or winnow to remove husks. Dry at 40–45°C if needed.

— Grinding: Grind thoroughly; whole seeds are hard to digest. Sift to reduce grittiness.

— Features: Rich in protein, iron, phosphorus, and magnesium. Similar to quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa), but milder. Gluten-free. Ideal for flatbreads (1 part orache flour to 4 parts regular flour), porridge, or thickening soups. Store in a dry, airtight container.

Flax seeds (Linum usitatissimum)

— Harvesting: Collected in late summer to early autumn when capsules turn brown and begin splitting.

— Preparation: Spread in a single layer in a warm, dry room (out of direct sunlight) for 5 to 7 days, stir occasionally.

— Grinding: Grind dry seeds in short pulses to avoid heating. Use immediately after grinding to prevent oil oxidation.

— Features: Rich in omega-3 fatty acids, fibre, and protein. Nutty, oily flavour. Mix with wheat or rye flour (10–20%) in baked goods for added nutrition and moisture retention.

Hemp seeds (Cannabis ruderalis)

— Harvesting: Late summer to early autumn, when seeds detach easily. C. ruderalis is a wild, low-THC variety found in Russia, Kazakhstan, and Northern Europe.

— Preparation: Rinse to remove dust and fibres, then dry in a warm, ventilated area or at 40–45°C until crisp.

— Grinding: Grind in a coffee grinder. Shell fragments may remain, adding texture and a slight bitterness.

— Features: High in complete plant protein, essential fats, and B vitamins. Nutty, slightly bitter taste. Use (up to 15–20%) in energy bars, breads, pancakes, or biscuits. Adds moisture and elasticity to dough.

Amaranth seeds (Amaranthus retroflexus)

— Preparation: Dry collected heads on cloth in shade for 3 to 4 days. Thresh gently; sift out chaff. Dry seeds at room temperature or at 40–45°C for 1–2 hours.

— Grinding: Grind to coarse or fine flour; sift to improve texture.

— Features: Up to 18% protein, plus calcium, iron, and antioxidants. Gluten-free with mild, nutty-herbal flavour. Use in baked goods, porridge, patties, or energy mixes. Limit to 20–25% in dough due to low binding strength.

Sorrel seeds (Rumex acetosa)

— Harvesting: Late June to early July, when seed heads turn pale brown and pods detach easily. Cut tops with stems and place in cloth bags to prevent seed loss.

— Preparation: Spread in a ventilated, shaded area on paper or cloth for 2 to 3 days. Thresh gently; sieve to remove chaff. Dry further at room temp or at 40–45°C if needed.

— Grinding: Use mortar or grinder in short pulses to avoid overheating. Sift for fine, creamy flour.

— Features: Rich in organic acids, fibre, vitamin C, magnesium, and calcium. Mild sour, grassy taste. Add 10–15% to rye or wheat flour for tang and nutrition. Also suitable for thickening soups and sauces (up to 20%).

Willowherb seeds (Chamaenerion angustifolium)

— Harvesting: Ripen late July to August. Capsules turn brown and open easily. Harvest on dry days by cutting upper stems.

— Preparation: Dry in a shaded, ventilated area for 3 to 4 days. Separate seeds from fluff using a funnel or sieve. Dry at 40–45°C if needed.

— Grinding: Grind in short pulses (10–15 seconds) to avoid overheating. Sift to remove fibre.

— Features: Rich in plant oils, protein, and antioxidants. Nutty-honey aroma. Adds moisture and softness to gluten-free dough (use up to 10–15%). Great in pancakes, muffins, porridge, and bars. Store airtight in a cool, dark place.

Acorn flour (Quercus spp.)

— Harvesting: Collect in autumn (September — October) when acorns fall naturally. Choose clean, undamaged nuts.

— Preparation: Remove caps and shells. Cut and discard spoiled parts. Soak in cold water 3 to 5 days (changing water twice daily) or boil in multiple changes to leach tannins.

— Drying: After leaching, dry thoroughly in an oven (50°C, 2–4 hours) or air-dry in shade.

— Grinding: Grind into flour; sift for fine texture.

— Features: Gluten-free, high in starch, protein, and antioxidants. Nutty, caramel flavour. Ideal for scones, pancakes, biscuits, or porridge. Combine with other flours (30–40%) for structure.

Reindeer lichen (Cladonia rangiferina, C. stellaris)

— Harvesting: Late summer or autumn, in dry weather away from pollution. Choose clean, pale-grey specimens.

— Preparation: Rinse and soak in bicarbonate of soda solution (1 tsp per litre) for 1–2 days, changing once or twice. Rinse again.

— Drying: Air-dry in shade or use oven at ≤ 45°C until brittle.

— Grinding: Grind to powder or coarse meal. Sift for finer flour.

— Features: Low in starch, high in fibre and minerals, slightly bitter. Traditionally mixed with barley flour, mint, or berries. Use up to 10–15% in rye or oat dough. Store in airtight container.

Dough kneading techniques

Wild flours are often dense and gluten-free, so dough can be crumbly or inelastic. To improve texture:

— Combine different flours (e.g., root and seed) for balance.

— Add water gradually to avoid stickiness.

— Use binding agents such as starch, apple purée, or psyllium gel to help the dough hold together.

Recipes

Burdock root and nettle seed bread

Ingredients:

— 200 g burdock root flour

— 100 g nettle seed flour

— 1 tsp salt

— 1 tbsp honey

— 200 ml water

— 1 tsp bicarbonate of soda

Preparation:

Mix all ingredients thoroughly. Pour into a baking dish and bake at 180°C for 40–50 minutes.

Acorn flour tortillas

Ingredients:

— 150 g acorn flour

— 50 g orache flour

— ½ tsp salt

— 150 ml water

— 1 tbsp oil

Preparation:

Mix the ingredients to form a smooth, pliable dough. Divide and flatten into tortillas. Fry in a dry frying pan for 2–3 minutes on each side.

Biscuits with orache flour and linden flowers

Ingredients:

— 100 g orache flour

— 50 g dried linden blossoms

— 2 tbsp honey

— 50 ml water

— ½ tsp meadowsweet powder

Preparation:

Mix all ingredients. Shape into biscuits and bake at 160°C for 15–20 minutes.

Loaves from Inner bark (pine, elm, or birch)

Ingredients:

— 1½ cups (approx. 360 ml) inner bark (cambium), dried and ground

— ½ cup (approx. 120 ml) water

Preparation:

Combine into dough, shape into small loaves, and bake at 140°C for 20–25 minutes or cook over campfire embers.

Reed rhizome cakes

Ingredients:

— 1 cup (approx. 240 ml) crushed reed rhizomes

— ¼ cup (approx. 60 ml) water

— 2 tbsp plantain gel (optional)

Preparation:

Form into small cakes. Fry in a pan with or without oil for 4–5 minutes on each side.

Dandelion root bread

Ingredients:

— 1½ cups (approx. 360 ml) dandelion root flour (dried and ground)

— ½ cup (approx. 120 ml) water

Preparation:

Mix into dough, shape into loaves, and bake at 160°C for 20 minutes.

Sorrel seed tortillas

Ingredients:

— 1 cup (approx. 240 ml) ground sorrel seeds

— ⅓ cup (approx. 80 ml) water

— Salt to taste

Preparation:

Mix, knead into dough, shape tortillas, and fry for 3 minutes per side.

Nettle seed tortillas

Ingredients:

— 1 cup (approx. 240 ml) nettle seeds

— ½ cup (approx. 120 ml) water

— 1 tbsp plantain gel (optional)

Preparation:

Knead into soft dough, shape into tortillas, and fry for 3–4 minutes on each side.

Cattail rhizome bread

Ingredients:

— 1½ cups (approx. 360 ml) cattail rhizome flour

— ⅓ cup (approx. 80 ml) water

Preparation:

Mix, shape into loaves, and either sun-dry thoroughly or bake at 140°C for 20–25 minutes.

Willowherb seed tortillas

Ingredients:

— 1 cup (approx. 240 ml) willowherb seeds (cleaned and ground)

— ½ cup (approx. 120 ml) water

— Salt to taste

Preparation:

Form tortillas and fry in a dry pan for 3 minutes per side.

Yagel (reindeer lichen) loaves

Ingredients:

— 1 cup (approx. 240 ml) reindeer lichen flour

— ½ cup (approx. 120 ml) water

— Salt to taste

Preparation:

— Mix flour, water, and salt into a soft dough.

— Shape into small loaves.

— Bake at 150°C for 25 minutes.

Baking without yeast

Yeast is not available in the wild, but it can be easily replaced:

— Bicarbonate of soda and acid (e.g., berries, vinegar) — together they produce gas bubbles.

— Fermented drinks — herbal kvass (fermented rye drink, a traditional Slavic beverage) can serve as a natural leavening agent.

— Incorporated air — manually beating the dough can trap air and create a lighter texture.

Sourdough recipes

Simple starter (fermenting base) made from hops

Ingredients:

• A handful of dried hop cones (Humulus lupulus)

• 2 cups (approx. 480 ml) water

• 1 cup (approx. 240 ml) flour

• 1 tbsp honey or jam (optional)

Preparation:

— Boil the hop cones in water for 15 minutes.

— Allow the liquid to cool, then strain.

— Add the flour (and honey or jam, if using) and stir — the consistency should resemble single cream.

— Cover with a cloth and leave in a warm place for 1–2 days.

— When bubbles appear and a pleasantly sour aroma develops, the starter is ready.

Use: Ideal for baking bread, making pancakes, or preparing kvass. Keep in the fridge and refresh regularly with flour and water.

Hay (herbal) starter

Ingredients:

• A handful of dry hay or aromatic herbs (e.g. mint (Mentha spp.), St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum))

• 1 litre water

• 2 tbsp sugar or honey

Preparation:

— Pour boiling water over the hay or herbs and stir in the sugar or honey.

— Cover, allow to cool, and leave in a warm place for 2–3 days.

— Strain — the result is a fragrant, living starter.

Use: Perfect for brewing bread kvass, fermenting herbal drinks, or as a base for other wild fermentations.

Tips and recommendations

— Experiment with different flour combinations.

— Adjust recipes based on the moisture content of wild flours.

— Use natural sweeteners such as honey or berry syrup.

— Store flour in a cool, dry place in airtight containers.

FINAL NOTE

Baking with wild plants is more than just a way to diversify your diet — it is a chance to reconnect with ancient traditions, when people lived in harmony with nature. By using flour made from roots, seeds, and other wild ingredients, you can create unique, delicious, and nutritious dishes.

Chapter 4. Wild Plant Vinegars

Vinegar is not merely a condiment, but an ancient elixir, valued by our ancestors for its flavour, healing properties, and ability to preserve food. In the wild kitchen, vinegar made from flowers, berries, and herbs is a universal remedy — for nourishment, for medicine, and for preservation. It accompanied travellers and herbalists alike as a source of vitality and taste.

In this chapter, we shall delve into the art of making vinegars from wild plants. You will discover how to transform the simplest gifts of nature into a fragrant and health-giving base for marinades, sauces, and dressings. Such vinegars not only lend dishes a delicate tang, but also enrich them with a bouquet ranging from floral to spicy, from fruity to resinous.

Vinegar as a gift of nature

Vinegar is among the oldest products known to humankind. As early as Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, it was obtained from fermented fruits and herbs and used as a drink, a medicine, an antiseptic, and a flavouring. It was both a household necessity and a magical substance.

In the tradition of wild cuisine, vinegar is a way to preserve summer in a bottle: the sunlit taste of berries, the fragrance of meadow herbs, the subtle tartness of wild fruits. Wild plants — nettle, dandelion, blackthorn, meadowsweet, maple — impart vinegars with distinctive, often layered flavours and rich colours.

Homemade vinegars from wild plants are a simple craft with great potential. They can replace factory-made condiments, elevate even the humblest dishes, serve as a base for dressings, drinks, and fermented foods, and even become part of your natural medicine chest.

In this chapter, you will learn how to make vinegars from foraged ingredients — aromatic, healing, and unique. They will enrich your cooking and bring true character to your pantry.

The basics of vinegar making

Vinegar is formed through a two-stage fermentation. First, the sugars contained in the raw material are converted into alcohol by yeasts; then the alcohol is transformed into acetic acid by bacteria (Acetobacter). Here are the main steps of the process:

1. Choosing raw materials

A wide range of plants can be used for vinegar fermentation, such as:

Flowers (dandelion, elderflower)

Berries (sloe, rosehip)

Herbs (nettle, ground elder)

It is essential that the plants are fresh, clean, and free from mould or contamination.

2. Fermentation base

To begin fermentation, you will need:

Ready-made vinegar (apple cider, wine), which already contains the bacteria required to turn alcohol into vinegar.

Vinegar mother — a gelatinous mass formed during previous fermentation, serving as a source of bacteria for the next batch.

Alternatively, sweetened water (water with sugar) can be used to supply sugar for the initial fermentation, if you do not have vinegar to hand.

3. Fermentation process

Preparing the raw material: Wash the plants, and chop them if necessary to speed up the release of aroma and active compounds. Berries may be lightly crushed or left whole.

Filling the vessel: Place the raw material into a clean glass jar, cover with vinegar (or sweetened water), leaving sufficient headspace for fermentation. To activate fermentation, add a little ready-made vinegar or vinegar mother, ensuring the presence of the right bacteria.

Starting fermentation: Cover the vessel with muslin or cloth to allow oxygen in, as bacteria require it to work. Keep the jar in a warm place (20–30°C). A stable temperature is important, as it affects the speed of fermentation.

Infusion: Over 2–4 weeks, the mixture will ferment. Check it regularly, noting aroma and flavour. The taste should gradually sharpen, and bubbles will appear — a sign of alcohol turning into vinegar.

4. Fermentation conditions

1. Use glass vessels (jars or bottles), which do not react with acid.

2. Cover with cloth or muslin to allow airflow while keeping out dust and insects.

3. Maintain a temperature of 20–30°C to ensure effective fermentation.

5. Filtering

Once fermentation is complete (when the vinegar has become sufficiently sharp), strain the liquid through muslin or a sieve to remove plant residues. Decant into sterilised bottles or jars for storage.

Tips:

If the vinegar becomes cloudy, develops an unpleasant odour or taste, it is best to start again. Check the cleanliness of your raw material, vessels, and the stability of the temperature.

Take care to prevent undesirable microorganisms entering during fermentation, as they may spoil the product.

Uses of vinegars

Culinary: Salad dressings, vegetable marinades, sauces.

Health: Dilute 1 teaspoon of vinegar in a glass of water as a morning tonic.

Household: Use as a hair rinse or a natural cleaning solution.

Tip: Store vinegar in a cool, dark place to preserve its aroma.

Vinegar recipes without sugar

Apple vinegar from peel and cores

A simple peasant method of preparation, using leftovers after preserving apples.

Ingredients:

— Peel and cores from 5–7 apples (preferably wild or sharp-tasting)

— 1 litre of water

— 1 tbsp of old vinegar (or leave out)

Preparation:

— Place the apple scraps in a jar and cover with water.

— Cover with muslin and leave in a warm place.

— After 5–7 days fermentation will begin. Stir daily.

— After 2–3 weeks, strain and leave to mature for another 1–2 weeks.

— Filter the finished vinegar and store in a bottle.

Uses: For food and as a healing remedy — especially diluted, to ease fatigue and aid digestion.

Herbal vinegar from sour infusions

A recipe using any sour-tasting herbs, especially sorrel.

Ingredients:

— A bunch of sorrel or ground elder (young leaves)

— 1 litre of rainwater or spring water

— A little old vinegar (optional)

Preparation:

— Chop the herbs and cover with water.

— Leave in a warm place for 2–3 days until fermentation begins.

— Strain, add a little vinegar as a starter, and allow to ferment for a further 2 weeks.

— Decant into a bottle and leave for another week.

Notes: A light vinegar with a mineral, herbal flavour. Traditionally used for dressing dishes and for treating greens before drying.

Vinegar from sour berries (sloe, rowan, lingonberry)

A northern method of vinegar-making.

Ingredients:

— 1 cup of fresh sour berries (such as lingonberry, sloe, guelder rose)

— 1 litre of boiled or spring water

Preparation:

— Crush the berries and place in a jar with water.

— Cover with cloth and leave for 5–7 days.

— Stir daily, monitoring the fermentation.

— Once the flavour has become distinctly sour and sediment begins to form, strain and leave to mature for a further 1–2 weeks.

— Decant into bottles.

Uses: A base for marinades and drinks.

Grain vinegar from rye or wheat

An Old Russian method of obtaining vinegar from soured grain.

Ingredients:

— 1 cup of sprouted rye grain

— 1 litre of water

Preparation:

— Cover the sprouted grain with warm water and leave for 2 days.

— Strain, and leave the liquid in an open jar at room temperature.

— After 5–7 days a light vinegar aroma will appear. Strain and mature to the desired strength.

Notes: A little old vinegar or fermented liquid (such as sauerkraut brine) may be added.

Birch sap vinegar

A Siberian spring recipe — vinegar was prepared when the sap began to sour naturally.

Ingredients:

— 1 litre of fresh birch sap

Preparation:

— Leave the sap at room temperature in an open jar.

— It will first sour, then begin to turn into vinegar.

— After 10–14 days, filter and decant into a bottle.

Uses: In folk medicine, and as a refreshing seasoning.

Vinegar recipes with sugar

Apple vinegar

Ingredients:

— 1 kg of wild apples (peel and cores may also be used)

— 1 litre of water

— 100 g of sugar syrup or honey

— 1 tsp of starter (or 2 tablespoons of prepared apple vinegar)

Preparation:

— Chop the apples into small pieces together with the peel and place in a jar.

— Boil the water, dissolve the sugar or honey in it, and cool until lukewarm.

— Pour the sweetened water over the apples so that they are completely covered.

— Add vinegar or starter, cover the jar with muslin.

— Leave in a warm place for 2–4 weeks, stirring daily.

— When the liquid turns sour and the apples sink to the bottom, strain the vinegar.

— Bottle and store in a cool place.

Uses: A universal homemade vinegar for cooking and health purposes.

Linden иlossom мinegar

Ingredients:

— 1 cup of fresh or ½ cup of dried linden (lime) blossoms

— 1 litre of water

— 100 g of sugar syrup

— 1 tsp of vinegar starter or a little natural vinegar

Preparation:

— Pour boiling water over the linden blossoms and steep for 10–15 minutes.

— Strain the infusion, add sugar, and cool.

— Transfer into a glass container and add the starter.

— Cover with muslin and leave at room temperature for 3–4 weeks.

— Strain and bottle when ready.

Notes: Fragrant, floral vinegar with delicate flavour.

Ground elder vinegar

Ingredients:

— 2 cups of young ground elder leaves

— 1 litre of water

— 100 g of sugar syrup

— 1 tsp of starter or a little vinegar

Preparation:

— Wash and chop the ground elder leaves.

— Prepare the sweet water, then cool.

— Place the greens in a jar and pour in the sweetened water.

— Add the starter, cover with muslin.

— Leave in a warm place for 2–3 weeks, stirring daily.

— Strain the finished vinegar and bottle.

Notes: Herbaceous vinegar with a fresh, green aroma.

Hawthorn berry vinegar

Ingredients:

— 1 cup of fresh hawthorn berries

— 1 litre of water

— 100 g of honey or sugar syrup

— 1 tsp of starter or a little vinegar

Preparation:

— Lightly crush the berries to release juice.

— Prepare sweetened water and cool.

— Pour the liquid over the berries and add starter.

— Cover with muslin and leave for 3–4 weeks.

— When the liquid acquires a distinct sourness, strain and bottle.

Uses: Traditionally used as a tonic and in marinades.

Dandelion vinegar

Ingredients:

— 1 cup of dandelion blossoms

— 1 litre of water

— 100 g of sugar (or sugar syrup)

— 1 tsp of starter (or a little vinegar)

Preparation:

— Collect fresh dandelion blossoms, wash, and lightly dry.

— In a pan, boil the water, add sugar (or syrup), and stir until dissolved.

— Place the blossoms in a jar or pan and pour over the sweet water.

— Leave to cool to room temperature, then add starter (or vinegar).

— Cover with muslin and leave for 3–4 weeks to ferment.

— Check occasionally; when the vinegar reaches the desired acidity, strain and transfer to bottles.

Notes: Light floral vinegar with a springtime aroma.

Nettle vinegar

Ingredients:

— 1 cup of fresh nettle (young leaves preferred)

— 1 litre of water

— 100 g of sugar (or sugar syrup)

— 1 tsp of starter (or a little apple vinegar)

Preparation:

— Wash and chop the nettle leaves.In a pot or jar, boil the water, add sugar (or syrup), and dissolve completely.

— Place the nettle leaves in the hot water and leave to infuse until cooled to room temperature.

— Add the starter (or vinegar).

— Cover with cloth and leave in a warm place for 3–4 weeks. Check occasionally.

— When the vinegar reaches the desired acidity, strain and bottle.

Notes: Refreshing, slightly sharp vinegar with a herbal character.

Mint vinegar

Ingredients:

— 1 cup of fresh mint leaves

— 1 litre of water

— 100 g of sugar (or sugar syrup)

— 1 tsp of starter (or a little apple vinegar)

Preparation:

— Collect fresh mint leaves and wash thoroughly.

— In a pan, boil the water, add sugar, and dissolve.

— Place the mint leaves in a jar or pan and cover with the sweet water.

— Allow to cool to room temperature, then add the starter (or vinegar).

— Cover with muslin and leave in a warm place for 2–3 weeks.

— Strain and bottle when the vinegar reaches the desired flavour.

Notes: Cooling, aromatic vinegar, ideal for summer dishes.

General tips and recommendations

Choice of ingredients: Gather plants on dry mornings so that they are fresh and aromatic.

Storage: Vinegar keeps for up to 1 year in a dark, cool place. Use glass bottles with tight lids.

Experiments: Combine ingredients — for example, add rose hips to dandelions for a new flavour.

Cleanliness: Sterilise jars and bottles to prevent mould.

Economy: Leftover plant matter after straining can be used in sauces.

Tip: If the vinegar tastes too sharp, dilute with water before use.

FINAL NOTE

Vinegars made from wild plants are a way to preserve the flavour and benefits of forest herbs, berries, and blossoms. They bring a light tang, enhance flavour, and diversify everyday cooking. Easy to prepare, they provide a wholesome and tasty base for marinades, dressings, and drinks. By using nature’s gifts, you create natural products with a vivid character and a seasonal touch.

Chapter 5. Milk and dairy products from wild plants

Plant-based milk is more than a modern trend — it is rooted in ancient tradition practised by our ancestors for centuries. In times when cow’s or goat’s milk was not always available, people found ways to obtain nutritious drinks from the plants around them. Today, we are returning to this knowledge to create delicious and healthy alternatives that not only diversify our diet but also bring the vitality and richness of the wild.

Milk from nature

Plant-based milk is more than just a substitute for animal milk — it is a unique product with its own flavour and texture. Rich in proteins, fats, and micronutrients, its preparation is both simple and fascinating. Using nature’s gifts, you can create beverages suitable for porridges, pastries, sauces — or simply to enjoy on their own.

Methods for making plant-based milk

The basic principle is to blend plant material with water and then strain it. However, each type of plant requires its own approach.

Milk from nuts

— Hazelnuts: Produces rich, buttery milk — perfect for porridges and desserts.

— Hazelnuts with linden flowers: An infusion of linden blossoms adds a gentle, honeyed note.

— Hazelnuts and hemp seeds: When blended, they form a creamy “butter” and thick milk — highly nutritious.

— Pine nuts: Resulting milk is creamy, with a light coniferous aroma — ideal as a base for cream or plant-based cheeses.

— Beechnuts: Delicate, slightly tart flavour — perfect for autumn porridges, puddings, and biscuits.

— Edible chestnuts: Produce thick, fragrant milk — great for desserts and sauces.

Tip: Nut milk may be sweetened with a little honey or seasoned with a pinch of sea salt.

Milk from seeds

— Nettle seeds: Delicate flavour with nutty undertones.

— Orache seeds: Nutritious and mild-tasting milk.

— Burdock seeds: Dense and oily — especially tasty in sauces and baked goods.

— Flax and amaranth seeds: Mucilaginous milk — excellent for digestive health and gravies.

— Wild cumin and nettle seeds: Spicy, savoury milk — ideal for hot sauces and mushroom dishes.

— Horse sorrel seeds: Tangy and robust in flavour — pairs well with nuts and berries.

— Psyllium seeds: When blended, form a thick, gel-like consistency — a natural thickener.

— Shepherd’s purse seeds: A springtime ingredient that yields light milk — good for soups and mashed vegetables.

Tip: Seeds can be lightly toasted before grinding to enhance flavour — but only slightly, to avoid bitterness.

Milk from roots

— Dandelirn roots: Earthy taste with a slight bitterness.

— Burdock roots: Naturally sweet milk due to its inulin content.

— Cattail rhizomes: After cooking, they turn into a creamy purée — a substitute for thick cream.

— Tip: Milk made from roots is particularly suited to thick soups and hearty porridges, offering earthy depth and natural sweetness.

Milk from sprouts and flowers

— Sprouted clover: Produces a vitamin-rich, refreshing milk.

— Linden blossoms: Brewed and blended with nettle powder into a creamy, milky mass.

— Pine pollen: When added to nut milk, it creates a fragrant “cream”.

Recipes for plant-based milk and thick bases

Milk from hazelnuts

Ingredients:

• 100 g hazelnuts

• 300 ml water

• Optional: 1 tsp honey or a pinch of salt

Preparation:

— Soak the nuts for 8–12 hours.

— Drain and rinse.

— Blend with fresh water.

— Strain through muslin cloth or a fine sieve.

— Add honey or salt, if desired.

Features: Requires soaking for better digestibility.

Taste: Delicate, creamy, slightly sweet.

Usage: Porridges, smoothies, baking.

Milk from pine nuts

Ingredients:

• 100 g pine nuts

• 400 ml water

Preparation:

— Blend the nuts with water.

— Strain.

Features: No soaking needed.

Taste: Rich, soft, with a light resinous note.

Usage: Cream soups, sauces, desserts.

Milk from beechnuts

Ingredients:

• 100 g beechnuts

• 300 ml water

Preparation:

— Soak overnight, then rinse.

— Scald with boiling water and chill to peel faster (optional).

— Blend with water.

— Strain.

Taste: Creamy, with a slight woody bitterness.

Usage: Autumn baking, puddings.

Milk from edible chestnuts

Ingredients:

• 100 g boiled chestnuts

• 250 ml water

Preparation:

— Blend with water.

— Strain.

Features: Use only edible chestnuts.

Taste: Mild, creamy, slightly sweet.

Usage: Desserts, especially with spices.

Milk from nettle seeds

Ingredients:

• 50 g dried nettle seeds

• 250 ml water

Preparation:

— Grind to powder.

— Blend with water for 1–2 minutes.

— Strain.

Features: Rich in protein and trace minerals.

Taste: Light, slightly herbaceous.

Usage: Smoothies, pastries, sauces.

Milk from orache seeds

Ingredients:

• 3 tbsp orache seeds

• 300 ml water

Preparation:

— Soak for 6–8 hours.

— Discard soaking water.

— Blend with fresh water.

— Strain.

Taste: Mild, nutty, slightly grainy.

Usage: Porridge, set milk dessert.

Milk from burdock seeds

Ingredients:

• 50 g dried seeds

• 200 ml water

Preparation:

— Grind seeds.

— Blend with water.

— Strain.

Features: Light detox effect.

Taste: Mild, earthy.

Usage: Soups, gravies, baking.

Milk from flax and amaranth seeds

Ingredients:

• 1 tbsp flax seeds

• 1 tbsp amaranth seeds

• 400 ml warm water

Preparation:

— Soak in warm water overnight.

— Blend until slightly mucilaginous.

— Strain if desired.

Features:

— Flax gives mucilage — good for digestion.

— Amaranth adds calcium and protein.

Taste: Mild, grainy-nutty, with a smooth texture.

Usage: Gravy base, porridges, baking.

Tip: No need to strain if you prefer a thicker consistency.

Milk from wild cumin and nettle seeds

Ingredients:

• 1 tsp wild cumin

• 1 tbsp nettle seeds

• 300 ml hot water

Preparation:

— Lightly toast cumin.

— Grind both seeds.

— Pour hot water and let infuse for 20 minutes.

— Blend and strain.

Features: Aids digestion.

Taste: Spicy and bold.

Usage: Mushroom dishes, sauces.

Milk from horse sorrel seeds

Ingredients:

• 2 tbsp seeds

• 300 ml water

Preparation:

— Grind to powder.

— Blend with water.

— Strain.

Features: High in antioxidants.

Taste: Tart and strong.

Usage: Soups, porridge, with berries and nuts.

Milk from shepherd’s purse seeds

Ingredients:

• 1½ tbsp seeds

• 300 ml warm water

Preparation:

— Slightly crush seeds before soaking.

— Soak for 6–8 hours.

— Blend until smooth.

— Strain.

Features: Supports urinary health.

Taste: Mild, herbal.

Usage: Spring soups, purées, dressings.

Milk from burdock roots

Ingredients:

• 100 g fresh roots

• 400 ml water

Preparation:

— Clean and cut roots.

— Soak for 8–10 hours.

— Simmer gently for 15–20 minutes.

— Blend with the cooking water.

— Strain.

Features: Prebiotic effect.

Taste: Naturally sweet.

Usage: Drinks, porridges, soups, baking.

Milk from cattail rhizomes

Ingredients:

• 200 g fresh rhizomes

• 300–350 ml water

Preparation:

— Clean and cut rhizomes.

— Boil for 15–20 minutes.

— Reserve about 50 ml broth.

— Blend rhizomes with the broth.

— Strain if desired.

Features: Starchy and filling.

Taste: Neutral, slightly starchy.

Usage: Cream substitute, puddings, sweet breakfasts.

Tip: Reduce the broth for a thicker result.

Milk from dandelion roots

Ingredients:

• 100 g fresh roots

• 300 ml water

Preparation:

— Clean and cut.

— Boil for 10 minutes, then cool.

— Blend and strain.

Features: Stimulates liver function.

Taste: Light bitterness, floral aftertaste.

Usage: Smoothies, sauces.

Tip: Light dry-roasting removes excess bitterness.

Milk from clover sprouts

Ingredients:

• A handful of sprouts

• 200 ml water

Preparation:

— Rinse and blend.

— Strain.

Features: Rich in phytoestrogens and antioxidants.

Taste: Light, herbal.

Usage: Smoothies, teas, or as a base for dressings.

Tip: A few drops of vinegar brighten the taste.

Linden blossom infusion-milk

Ingredients:

• 1 tbsp linden blossoms

• 150 ml boiling water

• 1 tsp nettle powder

Preparation:

— Brew blossoms for 15 minutes.

— Add nettle powder and blend.

Features: Soothing and vitamin-rich.

Taste: Delicate, floral sweetness.

Usage: Light milk, cream base.

Tip: Lightly bruise flowers for a stronger flavour.

Using plant milk

— Drinks: Enjoy warm or chilled, optionally sweetened with honey.

— Cooking: Add to porridges, soups, and sauces.

— Baking: Use as a substitute for animal milk in recipes.

Tips and recommendations

— Store for no more than 3 days in the refrigerator.

— Use clean utensils to prevent spoilage.

— Experiment with additions: herbs, berries, and spices.

Fermentation basics: turning milk into yoghurt and cheese

Fermentation is a natural way to preserve plant-based dairy alternatives. Beneficial bacteria convert sugars into acids, producing a pleasantly sour flavour and thicker texture. Here’s what you need to know:

Base: Use milk made from nuts (e.g., hazelnuts, pine nuts), seeds (e.g., nettle, orache), or roots (e.g., dandelion, burdock).

Starter culture: Choose from:

— Probiotic capsules (available at pharmacies; contain beneficial bacteria)

— A spoonful of live culture yoghurt

— Fermented herbal infusion (e.g., elderflower or fireweed tea)

— Sourdough kvass

Conditions: Ferment at 30–40°C for 6–24 hours using a yoghurt maker, warm oven, or insulated container.

Control: Taste after 6–8 hours. If too mild, continue fermenting.

Tip: Cleanliness is crucial. Sterilize jars and utensils to avoid contamination with unwanted microbes.

Techniques for making cheese and cream

After fermentation, plant milk can be turned into cheese or cream:

For Cheese:

— Strain the fermented milk through muslin cloth to separate the whey.

— Add herbs, spices, or salt to enhance flavour.

— Press the curds: 12–24 hours for soft cheese, 1–2 weeks for hard cheese.

For Cream:

— Blend cooked roots, sprouts, or nut pulp with a small amount of water.

— Strain for a smooth consistency, or leave the fibres for added richness.

Tip: Do not discard the whey — it can be reused in soups, baking, or for fermenting drinks.

Recipes for fermented foods

Fermented milk drink with herbs

Ingredients:

— 500 ml nut or seed milk

— 1 tsp nettle, mint, or meadowsweet powder

— 2 tbsp starter (rye kvass, berry infusion, or plant-based yoghurt)

Preparation:

— Heat the milk to 35–38°C.

— Add the starter and herbs; stir well.

— Pour into a glass jar, cover, and leave in a warm place for 12–24 hours.

— Strain through a sieve or muslin cloth.

— Chill before serving.

Features: A probiotic-rich base with herbal phytonutrients.

Flavour: Mildly sour with a gentle herbal aftertaste.

Use: A refreshing summer drink or a light snack.

Tip: Store in the fridge for up to 3 days.

Plant-based kefir with kvass

Ingredients:

— 500 ml nut or seed milk

— 100 ml fermented berry infusion or rye kvass

Preparation:

— Mix the milk and infusion.

— Leave in a warm place for 1 to 2 days.

— Chill the finished drink.

Features: A simple alternative to traditional kefir without dairy or commercial starter.

Flavour: Tangy and fresh, with subtle berry or bread notes.

Use: A thirst-quenching summer drink that supports digestion.

Tip: Great in green smoothies or on its own.

Fermented beverage made from ground elder

Ingredients:

— 500 ml milk made from ground elder

— 2 tbsp berry or bread-based starter

Preparation:

— Mix the milk with the starter.

— Leave in a warm place for 12–24 hours.

— When light gas bubbles appear, the drink is ready.

— Chill before serving.

Features: Contains B vitamins and natural enzymes.

Flavour: Mild, herbal, slightly tart.

Use: A revitalising summer drink.

Tip: Best served chilled in the morning or afternoon as a kefir alternative.

Plant-based yoghurt recipes

Witch hazel yoghurt with elderflowers

Ingredients:

— 500 ml hazelnut milk

— 50 ml elderflower infusion

— 2 tbsp live culture yoghurt or 100 ml berry/rye starter

Preparation:

— Heat the milk to 38–40°C.

— Add the elderflower infusion and starter; mix well.

— Pour into a glass jar, cover, wrap, and leave in a warm place for 8–12 hours.

— Refrigerate the finished yoghurt.

Features: Elderflower enhances antiviral and cooling properties. The nut base provides richness and balances acidity.

Flavour: Light, floral — reminiscent of a summer morning.

Use: With berries, fruit, granola, or in sauces.

Tip: For a thicker texture, add psyllium gel (is a viscous substance formed when psyllium husk, a type of soluble fibre, absorbs water), agar-agar, or refrigerate for 2–3 hours after fermentation.

Nettle seed yoghurt with willowherb

Ingredients:

— 500 ml nettle seed milk

— 50 ml fermented willowherb (fireweed) infusion

— 2 tbsp live plant-based yoghurt or 100 ml rye/berry kvass

Preparation:

— Heat the milk to 38–40°C.

— Mix with the fermented infusion or starter.

— Pour into a glass jar, cover, and insulate.

— Leave in a warm place for 12–14 hours.

— Chill before serving.

Features: Nettle milk is rich in micronutrients; willowherb supports digestion and adds a mild, pleasant flavour.

Flavour: Earthy and slightly tart.

Use: In porridge, smoothies, or with nuts and jam.

Tip: If the yoghurt is too runny, add more starter or extend the fermentation time.

Plant-based cheeses and cheese-like products

Soft Cheese Made from Hazelnuts and Chives

Ingredients:

— 300 ml hazelnut milk

— 1 tsp chive powder

— 2 tbsp plant-based starter (e.g. oatmeal or berry kvass)

— 1 tsp vinegar

— Salt to taste

Preparation:

— Mix the milk with the starter; ferment in a warm place for 12 hours.

— Strain through muslin cloth.

— Add vinegar, salt, and chive powder.

— Wrap in muslin cloth and press for 8–12 hours.

Flavour: Delicate, slightly sour, with herbal notes.

Use: For sandwiches or vegetable platters.

Beech nut cheese with mint and thyme

Ingredients:

— 500 ml beech nut milk

— 2 tbsp bread kvass or plant-based yoghurt

— 1 tsp dried mint

— 1 tsp thyme

— ½ tsp salt

Preparation:

— Ferment the milk for 10–12 hours.

— Strain, then add herbs and salt.

— Wrap in muslin cloth and press gently.

Flavour: Dense and aromatic — perfect for snacks and salads.

Tip: A popular dairy-free cheese option for fresh dishes.

Cedar milk cheesecake

Ingredients:

— 500 ml cedar (pine nut) milk

— 1 tbsp vinegar

— ½ tsp salt

Preparation:

— Heat the milk to 60–70°C.

— Add vinegar — the milk will curdle.

— Drain through muslin cloth.

— Season with salt and press lightly.

Flavour: Crumbly and mildly salty.

Nettle and plantain cream cheese

Ingredients:

— 200 ml nettle milk

— 2 tsp boiled plantain seeds

— 1 tbsp dried nettles

— Salt and garlic, to taste

Preparation:

— Blend all ingredients until smooth and creamy.

— Chill before serving.

Flavour: Mild, herbal, and savoury.

Use: As a spread, filling, or dressing.

Hazelnut mascarpone

Ingredients:

— 300 ml full-fat hazelnut milk

— 1 tsp vinegar

Preparation:

— Heat the milk gently, then add the vinegar and stir.

— Blend or whisk until thick and creamy.

Flavour: Soft, creamy, and delicate.

Use: In desserts, with fruit, or as a cream layer.

Cream and double cream recipes

Pine nut cream

Ingredients:

— 1 cup (approx. 240 ml) pine nuts

— 1,5 cups (approx. 360 ml) water

Preparation:

Blend until smooth. Do not strain.

Flavour and Texture: Delicate, thick.

Uses: Desserts, sauces, cream soups.

Fermented clover milk and thyme cream

Ingredients:

— 300 ml clover seed milk

— 1 tbsp thyme infusion

— 2 tbsp berry infusion (as a starter)

Preparation:

Mix all ingredients and leave in a warm place for 24–36 hours.

Flavour: Herbal, slightly spicy.

Uses: With vegetables, bread, or fresh berries.

Cream from pine pollen and nut pulp

Ingredients:

— 1 tsp pine pollen

— 3 tbsp nut pulp (leftover from milk-making)

— 100 ml water

Preparation:

— Blend all ingredients until smooth.

— Add more water if necessary to adjust the consistency.

Flavour: Lightly nutty with a pine note.

Uses: Desserts, herbal sauces.

Nettle milk and shepherd’s purse sour cream

Ingredients:

— 300 ml nettle milk

— 1 tsp shepherd’s purse seeds

Preparation:

Simmer over low heat for 5–7 minutes until slightly thickened. Allow to cool.

Flavour: Mild, herbal.

Uses: In hot dishes, salads, or dressings.

Wild walnut and hemp seed butter

Ingredients:

— 2 tbsp wild walnuts (e.g. hazel, beech)

— 1 tbsp hemp seeds

— 1 tsp vegetable oil

— Salt to taste

Preparation:

Grind into a paste, then whisk until light and airy.

Storage: Store in a sealed jar in the refrigerator for up to 5–7 days.

Uses: As a spread, or added to porridge and sandwiches.

Desserts and other recipes

Vegetable milk pudding with flax

Ingredients:

— 200 ml hornwort milk

— 1 tbsp ground linseed

— Honey or raspberry syrup, to taste

Preparation:

— Bring the milk to the boil, then add ground linseed.

— Simmer over low heat for 3–5 minutes until thickened.

— Allow to cool, then add honey or syrup.

Flavour: Delicate, with a slight nutty aftertaste.

Uses: Breakfast, dessert, fruit topping.

Tip: For a thicker texture, refrigerate for 1–2 hours.

Nettle milk and birch pollen cream

Ingredients:

— 300 ml nettle milk

— 1 tsp birch pollen

— 1 tsp honey

Preparation:

— Blend all ingredients until smooth.

— Best served chilled or fresh.

Flavour: Mild, sweet, and rich.

Uses: Cream for pancakes, fruit, or desserts.

Tip: Store in the fridge for no more than 24 hours.

Fruit pastila with lamb’s quarters milk and blueberries

Ingredients:

— 300 ml lamb’s quarters milk

— 100 g blueberries

Preparation:

— Blend the milk with the berries until thick.

— Spread into a 0.5–1 cm layer and dry at 40–45°C (in a dehydrator or oven) for 6–8 hours.

Flavour and Texture: Sweet and tart, soft and fruity.

Uses: Snack, children’s treat.

Tip: Can be rolled into spirals or cut into strips.

Set milk dessert with elderflowers

Ingredients:

— 200 ml lime-blossom milk

— 50 ml elderflower infusion

— 1 tsp ground plantain seeds

Preparation: