Бесплатный фрагмент - Etnography of North Russia and Hyperborea

Problems of localization of the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans

The problem of localization of the ancestral homeland of Indo-European peoples has been facing science for a long time. As far back as the mid-18th century, the linguistic kinship of European peoples was noted, and in 1767, Kerdu pointed out the proximity of a number of European languages to Sanskrit, the language of the sacred texts of Ancient India «Vedas. «The decisive for the emergence of Indo-European studies was the discovery of Sanskrit, acquaintance with the first texts on it and the enthusiasm that began with ancient Indian culture, the most striking reflection of which was the book of F. von Schlegel» On the language and wisdom of Indians ” (1808), writes V. N. Toporov. F. von Schlegel, the first to express the idea of a single ancestral home of all Indo-Europeans, placed this ancestral home on the territory of Hindustan. However, the fallacy of this assumption was soon proved, since before the arrival of the Aryan (Indo-European) tribes, India was inhabited by representatives of another language family and another one-time type — black Dravids.

Assumed at different times as the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans (today this is the people of 10 language groups: Indian, Iranian, Slavic, Baltic, German, Celtic, Romance, Albanian, Armenian and modern Greek): India, the slopes of the Himalayas, Central Asia, Asian steppes, Mesopotamia, Near and Middle East, Armenian Highlands, territories from Western France to the Urals between 60° and 45° N, territory from the Rhine to the Don, Black Sea-Caspian steppes, steppes from the Rhine to Hindu Kush, areas between the Mediterranean and Altai, in Western Europe — currently, for one reason or another, most researchers rejected.

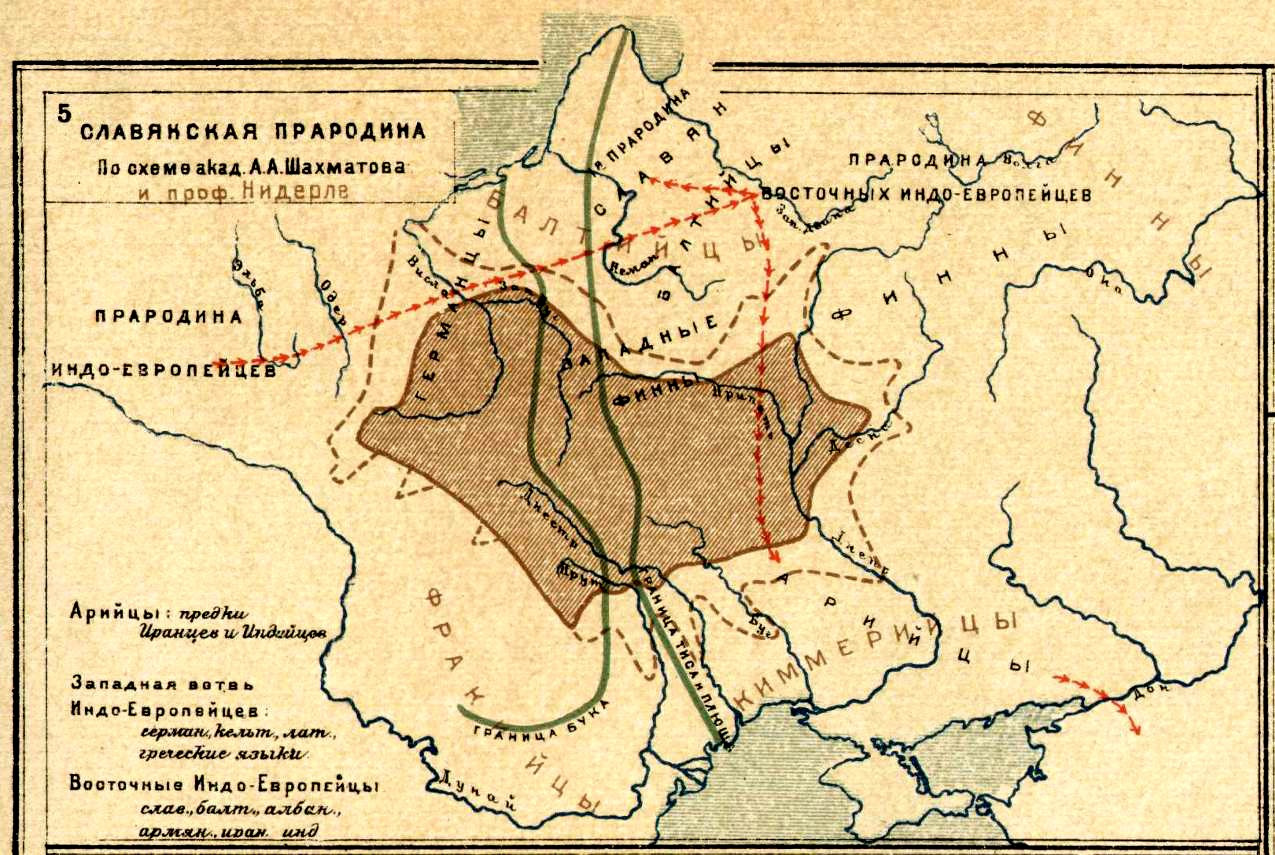

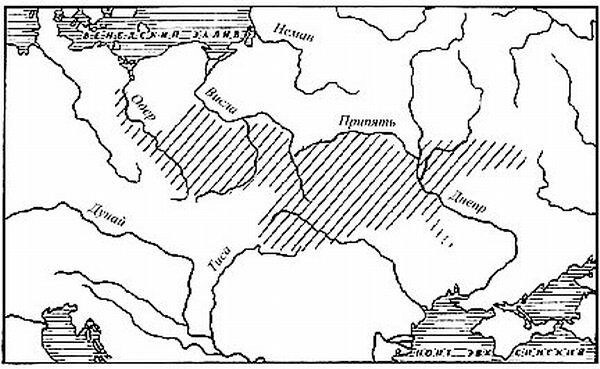

It should be noted that the Soviet historical school until the beginning of the 30s of the 20th century proceeded from the definition of the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans based on the works of A. A. Shakhmatov and L. I. Niederle. The ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans, based on naturally geographical factors, was placed by them in Moravia and Silesia. At the same time, the ancestral home of the East Indo-Europeans (Slavs, Albanians, summer-Lithuanians, Armenians, Indo-Iranians) was placed in the Moscow and Tver regions, in the upper Dnieper.

The ancestral home was placed by the Baltov in the Minsk and Vitebsk regions.

The ancestral home of the Slavs was located by them from Prussia to Pskov, along the banks of the Neman, Dvina and the Gulf of Riga. It was assumed that later the East Indo-Europeans moved south along the Dnieper, to the Black Sea, where the Aryans formed — the Indo-Iranians, who then left the Don to Iran and India. Slavs moved to Poland and further to the Balkans, Carpathians and Ukraine.

Similar scientific hypotheses were then replicated, in particular, in K. Kudryashov’s mass-circulation «Russian Historical Atlas» issued by the State Publishing House in 1928. Despite fundamentally different scientific views, this work was supported and approved by academicians M. N. Pokrovsky, S. F. Platonov, S. V. Voznesensky, B. D. Grekov, N. S. Derzhavin, Yu. G. Oksman, P F. Preobrazhensky, A. E. Presnyakov, O. N. Serbina, A. V. Shebalov.

But then, in 1929, «Russian history» itself was recognized as counter-revolutionary, and in 1932—36 the theory of the ancestral home was declared by communist ideologists — not Bolshevik, fascist and anti-scientific.

Among the hypotheses formulated in recent years, I would like to dwell on two in more detail: V. A. Safronov, who proposed in his monograph Indo-European Ancestral Homes the concept of the three ancestral homelands of Indo-Europeans —

in Asia Minor, the Balkans and Central Europe (Western Slovakia), and T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov, who own the idea of the Near-Asian (more precisely, located on the territory of the Armenian Highlands and adjacent areas of Western Asia) the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans, spelled out and argued by them in the fundamental two-volume «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans».

V. A. Safronov, referring to the work of N. D. Andreev, emphasizes that on the basis of the Early Indo-European (hereinafter RIE) vocabulary, we can conclude that «early Indo-European society lived in cold places, may be in the foothills, in which there were no large rivers, but rivulets, streams, springs; rivers, despite the rapid flow, were not an obstacle; crossed through them in boats. In winter, these rivers froze, and in spring they spilled scattered and swamps… The climate of the RIE ancestral homeland was probably sharply continental with severe and cold winters, when the rivers froze, strong winds blew; «in a stormy spring with thunderstorms, heavy snowmelt, river spills, hot dry summers when the grass was drying out, there was not enough water.» The early Indo-Europeans had early phases of agriculture and cattle breeding, although hunting, gathering and fishing did not lose their significance. Among the tamed animals are a bull, a cow, a sheep, a goat, a pig, a horse and a dog that guarded the herds. V. A. Safronov notes that: «Riding was practiced by the early Indo-Europeans: what animals were circled around is not clear, but the goals are obvious: taming.» Agriculture was represented by a hoe and fire-arm form, processing of agricultural products was carried out by grinding grain. The early Indo-European tribes lived settled; they had different types of stone and flint tools, knives, shelters, scrapers, axes, adzes, etc. They exchanged and traded. In the early Indo-European community, there was a difference in childbirth, taking into account the degree of kinship, and juxtaposition of friends and foes. The role of women was very high. Particular attention was paid to the «progeny generation process», which was expressed in a number of root words that passed into the Early Indo-European language from the boreal parent language.

In early Indo-European society, a paired family stood out, management was carried out by the leaders, and there was a defensive organization. There was a cult of fertility associated with zoomorphic cults, was a developed funeral rite. From the foregoing, V. A. Safronov concludes that the ancestral home of the early Indo-Europeans was in Asia Minor. He notes that such an assumption is the only possible, because: «Central Europe, including the Carpathian basin, was occupied by a glacier».

However, the data of paleoclimatology indicate something else. At the time in question, those during the final stage of the Valdai glaciation (the chronological framework of which is established from 11,000 to 10,500 years ago), the nature of the vegetation cover of Europe, although it was different from the modern one, but in Central Europe, arctic tundra with birch-spruce woodlands, low-mountain tundra and alpine meadows were common, not a glacier. Sparse forests with birch-pine stands occupied most of Central Europe, and steppe vegetation prevailed on the Great Central Danube Lowland and in the southern part of the Russian Plain.

Paleogeographers note that in the south of Europe the influence of the ice sheet was not felt, especially in the Balkans and Asia Minor, where the influence of the glacier was not felt at all. The time, to which the culture of Asia Minor Chatal Gayuk belongs, associated by V.A. Safonov with the early Indo-Europeans, marked by the warming of the Holocene.

As early as 9780 years ago, elms appear in the Yaroslavl Region, 9400 years ago in the Tver Region of lindens, 7790 years ago in the Leningrad Region, oaks.

The more unlikely the presence of a cold climate in Asia Minor. Here I would like to refer to the conclusions of L. S. Berg and G. N. Lisitsina, made at different times, but, nevertheless, not refuting each other. So L.S. Berg in his work «Climate and Life» (1947) emphasized that the climate of the Sinai Peninsula has not changed over the past 7 thousand years and that here and in Egypt, «if there was a change, it would rather increase, and not a decrease in precipitation».

He noted that: «Blankenhorn believed that in Egypt, Syria and Palestine the climate remained broadly constant and similar to that present since the end of the pluvial period; the end of the latter, Blankenhorn attributes to the beginning of the interglacial epoch» (130—70 thousand BC).

In his 1921 work, Blankenhorn writes that «From the Riess-Wurm interglacial (mousterien of Western Europe) to the present (in these territories) a dry desert climate, and in the north a semi-arid climate, similar to the modern one, interrupted by a short wet time corresponding to the Wurm glaciation.» G. N. Lisitsina comes to similar conclusions, who write in 1970: «The climate of the arid zone in the XVII millennia BC not much different from the modern one». We have no reason to believe that the climate of the west of Asia Minor, where daphne, cherry, barberry, maquis, Calabrian pine, oak, hornbeam, hop hornbeam, ash, white and prickly astragalus also live, also live animals like mongoose, jackal, porcupine, mouflon, wild ass, hyena, bats and locusts, and «snow does not fall every year, snow cover, as a rule, does not form», in 8—7 thousand BC so significantly different from the modern that it could be similar to that harsh ancestral home of the early Indo-Europeans, which is reconstructed on the basis of their vocabulary.

In addition, V. A. Safonov writes: «The close relationship between the boreal and the Turkic and Uralic languages, according to N. D Andreyev, allows localization of the boreal community in the forest zone from the Rhine to Altai.

From this it also follows that from all areas where RIE carriers could have gone, Anatolia seems to be the only possible one: narrow straits did not serve as an obstacle, since the early Indo-Europeans knew the means of crossing (the «boat» was recorded in the language of the early Indo-Europeans).»

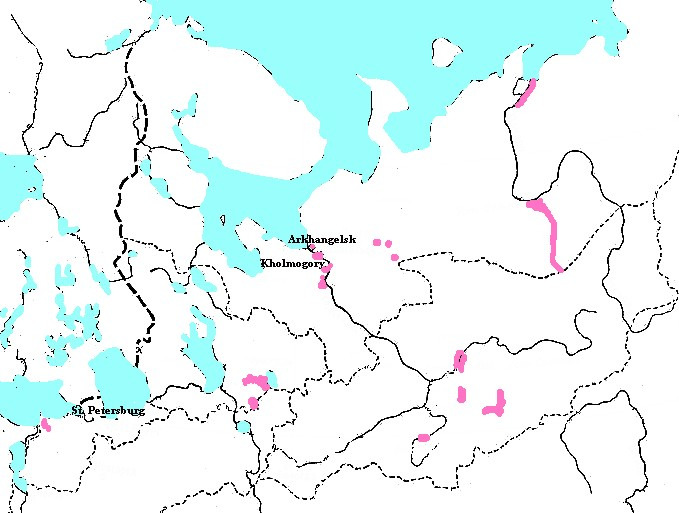

Recall that according to the conclusions of N. D. Andreev: «Of the landscape vocabulary in the boreal proto-language, root words are most abundantly represented, one way or another connected with the forest. The image of this row clearly indicates, firstly, the wooded nature of the area where the tribes who spoke BP lived, and secondly, the presence of conifers in these forests.» But a strip of coniferous forests at 10—9 thousand BC stretched not from the Rhine to Altai (in a latitudinal direction, as N. D. Andreev suggests and after him V. A. Safronov), but submeredionally from the southwest (from the foothills of the Carpathians) to the northeast (to Pechora). Consequently, the early Indo-Europeans from this forest zone could begin their progress in all directions (including to the territory of Asia Minor), from which, naturally, it does not follow that the population of Chatal Guyuk at the end of the 8th-beginning of the 7th millennium BC as not Indo-European. It is likely that Chatal Guyuk was only a small part of the vast early Indo-European range. Recall that this time (7 thousand BC) was the time of the peak of mixed deciduous forests, reaching in the north of Eastern Europe to the coast of the White Sea, and that the early Indo-Europeans for livestock-farming (slash-and-burn agriculture) in complex with hunting, fishing and gathering required very large territories.

And although V. A. Safronov writes that: «At the beginning of the Mesolithic, the zone of the producing economy was extremely limited» and included «only the mountains of Zagros, Southeast Anatolia, Northern Syria, and also Palestine», the presence of a producing economy on the territory Eastern Europe in 7 thousand BC, as noted earlier, is evidenced by archaeological materials obtained in recent years. Again referring to the conclusions of G. N. Matyushin, we emphasize that on the border of 7—6 thousand BC in the Southern Urals, the presence of a domestic horse is recorded and the remains of domestic animals (goats, sheep, cattle, horses and dogs) have been found at 22 sites. Recall that this particular set of domesticated animals — bull, cow, sheep, goat, pig, horse and dog — was recorded in the vocabulary of the early Indo-Europeans. And, of course, the deep kinship, the ancestor of the early Indo-European proto-language — the ancient boreal (northern) language with the Uralic (Finno-Ugric) and Altai (Turkic) languages naturally follows from the localization of the tribes of the speakers of this boreal language in the era of the final of the Upper Paleolithic (15—10 thousand BC) precisely in the zone of mixed and coniferous forests, i.e. in Eastern Europe. The migrations of a part of the boreal tribes beyond the Urals, to the territory of Siberia and to the foothills of Altai are logical and explainable by the pressure of the population surplus in the territory of Eastern Europe during this period, which could be caused by the lack of hunting grounds in the hunting and fishing type of economy, when the optimal population density was 1 person by 30—40 sq. km.Such shifts in the subsequent Early Indo-European time could be very significant in all directions and «divert» part of the population of the Indo-European area up to the west of Asia Minor. J. Mellart, the discoverer of the culture of Chatal-Guyuk, noted that already 12 thousand years ago (i.e., 10 thousand BC) aliens appeared in these areas, whose associations «were larger and better organized than from their predecessors… These groups of Mesolithic people with their specialized tools, apparently, were descendants of the Upper Paleolithic hunters, however, only in one point — in Zardi, in the mountains of Zagros — materials have been found that allow talking about the arrival of carriers of this culture from the north — maybe to be from the Russian steppes, because of the Caucasus.»

Thus, without rejecting the idea that the population of Anatolia was 8—7 thousand BC Early Indo-European, who came from the territory of their ancient ancestral home — the forest zone of Eastern Europe, we can assume that most of the early Indo-Europeans continued to live precisely in this ancestral home, which is largely confirmed by the earlier findings of the American linguist P. Friedrich that: «Proto-Slavic, better than all other groups of Indo-European languages, preserved the Indo-European system of designating trees… in to a significant extent continued to live in a similar area.» The zone of mixed coniferous-deciduous forests, we repeat, already in 7 thousand BC reached on the territory of Eastern Europe up to the coast of the White Sea.

As for the role of the Early Indo-Europeans in the world historical process, it is difficult to disagree with the main conclusions of V. A. Safronov made in the final part of his work.

Indeed: «In solving the problem of the Indo-European ancestral home, which has worried scientists of many professions and various countries of the world for two centuries, he rightly sees the origins of the history and spiritual culture of the peoples of most of Europe, Australia, America… How their descendants, the Indo-Europeans of modern times, discovered the New World, so the Indo-Europeans of the Ancient World revealed to mankind the knowledge about the integrity of the earthly home, the unity of our planet… These discoveries would have remained nameless if the echoes of the great wanderings had not been retained in the Indo-European literatures, separated from us and from these events for thousands of years… Indo-European travels became possible thanks to the invention of wheeled transport by the Indo-Europeans in their midst (4 thousand BC)».

And we add, thanks to the domestication of the wild horse in the southern Russian steppes, already on the borderland 7—6 thousand BC. As N. N. Cherednichenko notes: «The spread of the harness horse from the Eurasian steppes is no longer in doubt… the process of horse domestication is carried out on the distant plains of the Eurasian steppe region… Thus, at present, we can only talk about the ways penetration of Indo-European horse breeding tribes of Eurasia to the East and the Mediterranean… Eurasia, thus, was the territory from where the chariots were brought by the Indo-European tribes to various regions of the Old World, which had a very significant impact on the political life of the Ancient East.

V. A. Safronov writes: «The period of general development of Indo-European peoples — the Proto-Indo-European period — was reflected in the amazing convergence of the great literatures of antiquity, such as the Avesta, Vedas, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Iliad, Odyssey, in the epics of the Scandinavians and Germans, Ossetians, legends and tales Slavic peoples. These reflections of the most complex motifs and plots of common Indo-European history in the oldest literatures and folklore, separated by millennia, fascinate and await their interpretation. However, the emergence of this literature became possible only thanks to the creation by the Proto-Indo-Europeans of the metric of verse and the art of poetic speech, which is the oldest in the world and dates back no later than the 4th millennium BC… Having created their own system of knowledge about the universe, which opened the way to civilization for mankind, the Proto-Indo-Europeans became the creators of the most ancient world civilization, which is 1000 years older than the civilizations of the Nile Valley and Mesopotamia. There is a paradox: linguists, having recreated the appearance of the Proto-Indo-European culture according to linguistics data, according to all the signs of the corresponding civilization, and having defined it as the most ancient in a number of known civilizations (V — IV millennium BC) could not cross the rubicon of the prevailing historical stereotypes that „light always comes from the East “, and limited themselves to looking for an equivalent to such a culture in the regions of the Ancient East (Gamkrelidze, Ivanov, 1984), leaving aside Europe as» the periphery of Middle Eastern civilizations «… The civilization of the Proto-Indo-Europeans turned out to be so high, stable and flexible that it survived and survived despite world cataclysms».

V. A. Safronov emphasizes that «It was the late Indo-European civilization that gave the world a great invention — wheel and wheeled transport, that it was the Indo-Europeans who created the nomadic economy,» which allowed them to go through the vast expanses of the Eurasian steppes, to reach China and India… We believe that the guarantee The sustainability of Indo-European culture was created by the Indo-Europeans. It is expressed in the model of the existence of culture as an open system with the inclusion of innovations that do not offend the foundations of its structure… As a form of existence with the world, the Indo-Europeans proposed a model that remained in all historical times — introducing factorial colonies into an indo-speaking and foreign culture environment and bringing them to the level of development of the metropolis. The combination of openness with tradition and innovation, the formula of which was found for each historical period of the development of Indo-European culture, ensured the preservation of Indo-European and universal values. ” We allowed ourselves such a long quotation, since it is difficult to more clearly, compactly and comprehensively determine the importance of the pre-Indo-European and early Indo-European culture for the destinies of mankind than it was done in the work of V. A. Safronov «Indo-European ancestral home».

«Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans»

The next fundamental work devoted to the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans, the main provisions of which I would like to dwell on, is the work of T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans», where the idea of a common Indo-European ancestral homeland on the territory of the Armenian Highland develops and is thoroughly argued and the adjoining regions of Western Asia, from where part of the Indo-European tribes then advanced into the Black Sea-Caspian steppes.

Paying tribute to the very high level of this encyclopedic work, which collected and analyzed a huge number of linguistic, historical facts, data from archeology and other related sciences, I would like to note that a number of provisions postulated by T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov cause very serious doubts. Thus, V. A. Safronov notes that: «The linguistic facts cited by Gamkrelidze and Ivanov in favor of the localization of the Indo-European ancestral home on the territory of the Armenian Highlands can receive other explanations. Lack of IE hydronymy in the specified area can only testify against the localization of the Indo-European ancestral home in it. The environmental data presented in the analyzed work contradicts such localization even more. On the territory of the Armenian Highlands, almost half of the animals, trees and plants indicated in the list of flora and fauna given by Gamkrelidze and Ivanov, reconstructed into a common Indo-European (aspen, hornbeam, yew, linden, heather, beaver, lynx, black grouse, salmon, elephant, monkey, crab)».

It is precisely on these ecological data given in the work of T. V. Gamkrelidze and Viach. Sun. Ivanova, I would like to dwell in more detail. The authors of the «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans», in support of their concept, indicate the most ancient names of trees recorded in the ancient Indo-European proto-language. This is birch, oak, beech, hornbeam, ash, aspen, poplar, yew, willow, willow, spruce, pine, fir, alder, walnut, apple, cherry, and dogwood.

As for the Armenian Highlands, at present it is a combination of folded-block ridges and tectonic depressions, often occupied by drainless saline lakes (Van, Urmia), and less often by flowing freshwater (Sevan). The deepest depressions are characterized by semi-desert and even desert landscape. «There are dry feather-grass-fescue steppes, turning into forb-grasses» in places in the middle regions (between 1000 m and 2300 m) there are dry sparse forests of deciduous oaks, pines and junipers. «On the Iranian highlands, in the Zagros mountains (on the western slopes and in the more humid northern part, between 1000 m and 1800 m), park oak forests with the participation of elm and maple are widespread, and in the valleys there are wild mulberries, poplar, oak, and figs. Due to the fact that in the period of the middle of the 1st millennium BC until now is defined by climatologists as a period of cooling and humidification in relation to the climatic optimum of the Holocene (4—3 thousand BC) and the previous time (7—5 thousand BC), there is no reason to assume in these southern territories there is a much more humid and colder climate at 7—3 thousand BC, i.e. time referred to in the work of T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov.

It should be noted that significant fact that the names of many trees are completely absent in the common Indo-European vocabulary, widespread in Anterior and Asia Minor since ancient times. These are: olive (the primary focus of morphogenesis in Asia Minor); apricot (which was even grown in Tripoli settlements in 4 thousand BC); edible chestnut, known in these territories from the Tertiary period; quince in the wild growing in northern Iran, Asia Minor and the Caucasus; loquat, in the wild distributed in the Caucasus, Crimea and the North.

Iran (the primary focus of shaping and introducing into the culture of Asia Minor); almonds (the primary focus of forming Asia and the surrounding areas); figs, found in the wild in the Near East, Asia Minor and the Mediterranean; and, finally, a date, the primary source of domestication of which is South Iran and Afghanistan, de this plant was introduced into the culture in 5—3 thousand BC.

This list can be greatly expanded. But even in such a fragmented form, he confirms that neither Front, nor Asia Minor, nor the Armenian Highlands could be the oldest ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans. And here again I would like to refer to the conclusion of P. Friedrich that: «the Pre-Slavic best of all other groups of Indo-European languages retained the Indo-European tree naming system», and «speakers of the common Slavic language lived in the ecological zone during the general Slavic period (in particular, defined by woody flora), similar or identical to the corresponding zone of the common Indo-European, and after the general Slavic period, the carriers of various Slavic dialects continued to a significant extent to live in a similar area».

Who are these Andronovites?

«I did not write anything about the original Indo-Aryans — about which -the ancestors of the people of Andronovo culture — archaeologists do not know anything yet, but they certainly existed» N. Chlenova.

Yes, they existed, but it should be written about the Andronovites in a broad sense, without taking the final decision on the question of whether they were Indo-Iranians or Iranians by language (although a significant part of the names of rivers, for example, on the territory of Srubnik and Andronovites, is recognized as Iranian). Indeed, some researchers, studying this problem, even came to the conclusion that the Andronovites were a «historical fiction», although most archaeologists and historians pay the most serious attention to the characteristics of the Andronovo culture, its distribution, the connection of Andronovites with other ethnic groups and their influence on the cultural development of these ethnic groups.

We can associate this influence with the period of the settlement of the Andronovites from the main centers of their folding in the middle and southern Urals and adjacent lands, i.e. with the period of their obvious separation from the array of Indo-Iranians, who are usually called by the common name of the Aryans (Aryans). The timing of this release has not yet been determined by researchers.

The monuments of the Andronovo culture, attributed to different periods of its historical development, differ markedly from one another. This should be considered the result of the mixing of separate groups of the Andronovites with other groups of the population that surrounded them or with whom they met, jointly settling in the same territory during their waste from the original common Indo-Iranian lands. Such contacts had to continue for a long time, otherwise archaeologists would not have found clear traces of their stay both in vast territories to the east of the Urals, and in some areas quite remote to the west of it.

The results of such mixing or combining them with other peoples include, quite obviously, the assimilation by these peoples of the elements of their language, which is supposed to be the Iranian language, from which Scythian subsequently developed.

Both branches of the Old Aryan (Indo-Iranian) language (the speakers of which in this collection are called Indo-speaking and Iranian-speaking) have left their noticeable traces on the territory of Eastern Europe — mainly in the vocabulary and names of some rivers. These names are often very persistent and persist for millennia.

Since in that distant era, writing did not yet exist, many words of the Andronovo language, like the forms, their economies and some trends of their religion, were reflected in the ancient parts of the Zoroastrian Avesta they created. The analysis of this monument made it possible to partially reconstruct the pictures of their life and ritual performances close to the Indo-lingual Aryans.

The discovery by archaeologists of many obvious traces of the Andronovo culture on vast lands east and southeast of the Urals makes it possible to identify the massive resettlement of Andronovites in Iran and in areas close to northwest India. It is not excluded that the battles of the Aryans with the Aryans described in the Avesta refer precisely to the border Iranian-Afghan and North Indian regions. It is difficult to define in another way such military contacts, if one does not take into account the fact that in the north-west of India already from the end of the 3rd and beginning of the 2nd millennium BC settled groups of Indo-speaking Aryans, coming wave after wave from the southeastern regions of Europe, mainly from the lands of the Northern Black Sea region. Subsequently, the gradual mixing of the Andronovites with the ancient Iranian (or, which is more often found in literature, the ancient Persian) society was promoted (and accelerated by this process) by the fact that representatives of the ruling dynasties adopted the religion of Zoroastrianism: in Parthia — the Arshakids (3rd century BC — 2nd century AD), and in Iran — the Sassanids (2nd -4th centuries AD).

The Avesta language was formed on the basis of ancient Iranian and ancient Indian dialects familiar to Andronovites (which dates back to the time of the existence of the Aryan, the ancient Indo-Iranian community, which was not divided into two branches). Apparently, that’s why the Avesta is so close to the Rigveda both in language and in the names of the gods.

Zarathushtra reformed common Indo-Iranian beliefs dating back to ancient times, and under the influence of these changes, some Aryan gods began to be described in the Avesta and perceived by the Iranians as enemies of the Zoroastrian gods. Such a transformation, like the folding of the Avesta itself, lasted for several centuries, although its authorship is attributed to one Zarathushtra, who lived at the turn of the 2nd and 1st millennia BC.

In the west, among the Indo-European peoples, there are relatively few Iranian borrowings taken from the Andronovites (the main borrowings from this language are associated with the Scythians, 1 millennium BC).

The Finno-Ugric tribes that lived in the Urals, in the Middle Volga region and beyond the Urals, gradually, over the course of a number of centuries, borrowed from the Aryans a certain number of words that are still preserved in their languages. The contacts of the Finno-Ugrians with the Aryans (or, as some scholars call them, common Indo-Iranians) took place in about the second half of the 2nd millennium BC and lasted until the Scythian time, the beginning of which is recognized as the 7th century BC.

Other influences of the Andronovo culture, in addition to borrowing a part from them, vocabulary, are not traced between representatives of these completely different two language families, although the existence of their cultures was almost synchronous.

It is even suggested that some Trans-Ural Finno-Ugric peoples were bilingual, they also knew the Iranian language.

As for the dating of the Andronovo culture, now there is a series of dates established by the radiocarbon method: in particular, the West Andronovo monuments date back to the second half — the end of the 2nd millennium BC.

An extremely interesting point for everyone who is attracted by the history of our distant ancestors is that in the ancient literature of Indo-speaking and Iranian- speaking Aryans, i.e. in the Vedas and Avesta there are indications that the Volga was known to the Aryans.

In the Rig Veda there is only one mention of it — in its 10th book, in the «Hymn to the Rivers,» it speaks of a certain river called the Race. Researchers consider it to be a tributary of the Indus, i.e. rivers on the lands of the settlement of Aryans in India, which had already passed into the realm of myths by some apparently half-forgotten river flowing in heaven.

In the Avesta, the Ranha River (Rangkha, Raha), flowing down from a high mountain, is chanted. Its upper reaches (this word is translated also as coasts) are captured by severe frosts — «the scourge of this country».

And if, as many scholars believe, the Indo-speaking branch of the Aryans left the lands of southeastern Europe east of the Andronovites, it is not surprising that in their memory the memories of this Race, explained as the Volga, were weaker than those of the Andronovites, who settled a considerable part of the coast Volga.

Their Ranha hydronym is close to the names of the Volga, such as Rava, Ravo, Rav, which, as many believe, are borrowed from the Aryan languages, preserved in Mordovian language, for example. So maybe Ranha is the Volga?

In the writings of the Greeks, the Volga is mentioned under the name Rha and Ra. And this series of names Rasa — Ranha — Rangha — Rava — Rha — Ra, in which the last three relate reliably to the Volga, makes us assert in the opinion that the ancient Aryans (both of their branches, but especially the Andronevites) knew the Volga. It is sometimes suggested that the Avestan Ranha could be both the Syr Darya and even the Kabul River in Afghanistan. But such assumptions are immediately crossed out by descriptions of frosts in the «country of this river», and the Avesta speaks of the amazing Ranha Delta, where it flows into the sea «with a whole thousand channels and a thousand lakes» (the anthem of Ardvi-Sure). This is an almost accurate indication of the Volga delta.

Zoroastrians in the Avesta liken the Ranha River to the great goddess Ardvi-Sur, «River-goddess Ardvi.» They glorify her as Ardvi full-flowing, wide and healing, growing vein, feeding herd and the size equal to «all waters taken together». But this entire still does not mean that the word «Ardvi» is a hydronym, i.e. the name of the river. No, this is her mythologized, heavenly name. She is the goddess of the river and it is often difficult to understand in the hymns which one is being discussed. For example: "...the good Ardvi flows from its Creator: beautiful white hands in spacious sleeves» or she "...in a chariot, holding a bridle, strives», and at the same time it flows down from the same mountain as the Ranha river and has a thousand channels. It is clear that by chanting the same object, under a real and celestial name.

It is said about the goddess Ardvi-Sura that she should make abundant sacrifices — a sacrifice that accompanies every appeal to the gods, this is the oldest custom of all the Aryan tribes — and in the Avesta the number of sacrificed animals is brought (as in the Rig Veda) to unprecedented, clearly mythologized volumes like a hundred stallions, a thousand cows and a myriad of sheep. But even such sacrifices do not achieve the goal, if Ardvi is asked to help defeat the Aryans — in this case, she invariably refuses the one asking. This means that the river-goddess, the patroness of the Aryans; was considered Ardvi-Ranha-Volga.

This cannot but be recognized as indisputable evidence of the stay of the Aryan tribes, and a long one, in Eastern Europe; and it is in the Volga and Ural lands. The northern nature is clearly stated in the hymn to Ardvi-Sura, in the description of the fact that four stallions are given to her: «Rain and Wind, Cloud and Hail, they constantly pour moisture… Innumerable snow and hail are poured on her… I pray to Mount Hukarya, ...from which the good Ardvi-Sura flows down to us.»

This is all too similar to the Volga, especially in its upper reaches, in the «country of frosts.» But a certain doubt here can be caused by the description of the high altitude of Mount Hukarya, which does not coincide with the Valdai Upland.

Where is this mountain? So let us remember that until relatively recently, the Kama or Belaya rivers were considered the beginning of the Volga. The Russians also call this last White Volozhka, i.e. «White Small Volga». This river really originates from Mount Tiremel, one of the two highest peaks of the Southern Urals (in the Avesta, the Ranha River flows down from a mountain of «a thousand men»).

This means that in this matter, doubts about the identity of Ranha and the Volga should disappear. It is also interesting that Ranha is glorified in the Avesta as a beautiful woman, dressed in a luxurious tuba of 300 beaver skins. Firstly, the very fact of the need to wear a fur coat sharply pushes the mother river from the southern countries to the north. And secondly, it should be remembered that beavers are not found in Iran, and only the Aryan-Andronovites could bring here memories of the need to resort to warm clothes in the winter, and the memory of beavers abundantly found throughout the Volga basin.

Combining all the above data together, we inevitably come to the conclusion — about the irrefutability of the identification of Ranha and Volga, as well as confirming the idea that that the Iranian-speaking branch of the Aryans — Andronovites — came to the southern countries precisely from the region of the Volga-Ural lands, where they lived until the end of the 2nd — beginning of the 1st millennium BC.

Chud

Priest A. Grandilevsky, narrating in 1910 about the homeland of M. V. Lomonosov, gives legends about the sanctuary «Chud idol of the god Iomally or Yumala», known from the descriptions of the 11th century, in connection with the city of Burma, which was on the banks of the Dvina and was a trading center of the edge. The legend says that in the rich cemetery in the middle «stood the idol of the god Iomalla or Yumalla, made very skillfully from the best tree: the idol was decorated with gold and precious stones… A golden crown with twelve rare stones shone on Yumalla’s head, his necklace was valued at 300 marks (150 pounds) of gold. On his lap stood a golden chalice filled with gold coins — a chalice so large that four people could get drunk out of it to the full. His clothes were superior in price to the cargo of the richest ships.»

The Icelandic chronicler Shturlezon, as A. Grandilevsky notes, «describes the same thing, mentions a silver bowl; the scientist Kostren confirms the narrative of folk legends about the treasures of the glorious people. One of these legends is listed in the memorial book of the Kurostrov church (sheet 1887, sheet 4 -th) reads:

«The idol of Yumaly was fused from silver and attached to the largest tree.» The very name of Yumal, Yomall or Yamal (recorded in the story about the campaign of the Norwegian Gund in 1025—1026 in Biarmia), surprisingly close to the name of the Vedic god of death, Yama (Yima); the possibility of such parallels convinces finding the idol in the cemetery and the fact that he was «attached to the largest tree.» Here, it is probably appropriate to recall the words of one of the texts of the Rig Veda, namely, «Conversation of a Boy with a Dead Father: I. Where under the divnifolia tree drinks with all the gods Yama our parent is the head of the clan there passes dear ancestors. We are this abode of Yama worship the gods blowing reeds decorate with laudatory stump.» (R.V.X.13)

And since the «temple of Yumalla (Yamal) was worshiped by the» gods as a home», there is nothing surprising in the fact that» Chud, coming to pray, sacrificed silver and gold into the bowl «and that» it was impossible to steal money or idol, because Chud she took good care of her god, constantly there were sentinels near him, so that they wouldn’t miss any thieves, springs were drawn near the idol, who would touch the idol, although with one finger, now the springs will sparkle, ring all kinds of bells and you won’t go anywhere…».

Note that Chud in the legends about her is constantly called the «white-eyed», which does not at all indicate the classic Finno-Ugric character of appearance, but on the contrary emphasizes the specific, inherent to the Northern Aryans exceptional light-eyedness.

A. Grandilevsky notes that in the memorial book of the Kurostrov Church it is written: «Until recently, this spruce was the subject of many superstitions… they were afraid to pass and pass by the spruce, especially at night, and schismatics considered it a sacred grove and buried there until 1840 the dead.» Thus, the spruce was considered sacred until 1840 among the Old Believers, which is generally not peculiar to the specifically Finno-Urian shrines.

It must be said that A. Grandilevsky (being a priest), nevertheless draws the following conclusion: «Culturally, the ancient Zavolotsky Chud, when it became already historically known, hardly differed much from the Kiev or Novgorod Slavs, it could hardly be in the category of half-savages, in the strictest sense of the word, because its development was far ahead of all other tribesmen… lived settled, having a capital… serf suburbs, graveyards and large settlements… your religious ritual… had princes to protect against enemies, erected pretty good urban or serf embankments… from prehistoric times, it had a very wide trade with the Scandinavians, Anglo-Saxons, with all Chud and Finnish peoples… Already Shturlezon, the Icelandic chronicler wrote about the fabulous riches of Yumalla, Norwegians were even interested in farming, which had taken root in the life of Zavolotsky Chud, and talked about him as an item worth special attention… The Dvinsky Zavolochye constituted the center of general attention and it was such only in the first quarter of the 11th century».

A. Grandilevsky derives from «Chudsky native dialect» such names as Dvina, Pechora, Kholmogory, Ranula, Kurya, Kurostrov, Nalostrov, etc. But today we know that such hydronyms as Dvina and Pechora are of Indo-European origin; Racula — finds parallels in Sanskrit, where — Ra — possessing, contributing, a kúla — herd, clan, flock, crowd, many, family, noble family, noble clan, union, household, home, home.

As for Kurya, Kur-islands and Nal-islands, their names are close to the names of the ancestors of the «northern Kuru» of Mahabharata (an ancient Aryan family) — Nalya and Kuru.

Here it makes sense to cite the text of A. Grandilevsky, who delightfully described these parts at the beginning of the 20th century: «And, one legend says, in the region where the city of Kholmogory and its suburbs is now, a half-wild man of chudin came in the name of Kur, with him his mother, and probably a wife and some of his relatives or fellow tribesmen. The aliens really liked the delightful terrain of the future Kholmogory, everything here was the best for them. in the vicinity, many lakes, magnificent spruce groves and impenetrable wilds of black wood, gloomy wooded ravines, grassy islands provided convenient places for animal hunting, and for fishing, and for bird hunting, and for peaceful domestic work, and to protect against the enemy. Here, in the summer and in the winter, the water expanse opened beautiful paths to anywhere; in short, whatever the half-wild son of nature would have wished for himself, ready-made stocks opened up for him everywhere. Huge herds of wild moose and deer ran in here; here constantly lived bears, wolves, foxes, ferrets, martens, ermines, arctic foxes, lynxes, wolverines, squirrels, hares, in countless numbers; Ducks, geese, swans, pockmarks, black grouse, cranes, partridges, etc.; rivers and lakes were teeming with fish; immense numbers of mushrooms and berries were born. In deep troughs there could be natural and convenient pens for catching animals, for baiting moose and deer. In countless lake reservoirs, in straits and inlets, there were magnificent places for fishing with wicker, tops and just for killing anything, and catching a water or forest bird with snares asked for any savage in its own hands, as an easy task… The courageous Kur of his loneliness was not horrified; he liked the new area so much that he decided to stay here forever, not inviting anyone except his few companions. And so he occupied a high round hill in the bend of the Strait of Dvina, which since then has received his name along with the hill. Kur lived with his mother and others, until his own family grew up; then the children remained with their father, and their grandmother and those who had come with him earlier moved west to the high hills beyond the Bystrokurka River, than the folk tradition explains the origin of the Matigorsk region… Due to special life conveniences, and the fact that the Chud tribe was never exterminated here, as happened in neighboring regions, it was never driven out by anyone, it did not wage war, and it lived a settled working life, the future Kholmogorsky district was quickly filled with a population that has grown into a whole powerful independent semi-wild people — Chud Zavolotskaya.»

It should be noted that further A. Grandilevsky describes this «half-wild» people in such a way that this definition becomes completely inappropriate. He writes: «He was so isolated among his fellow tribesmen as a separate way of life, and a noticeable increase in mental development, and a prominent authority in the field of religious cult, that without any struggle he took a weighty front-line position and, having spread its borders throughout the Dvina coast from The Wagoy River, was such an impressive force, even the wild Ugra, countless at that time, didn’t dare to measure it».

The desire, so characteristic of the authors of the beginning of our century, to show Zavolotskaya the Chud a semi-wild Finnish tribe, then assimilated by the Dnieper and Novgorod Slavs, who are at a higher cultural level, quite often leads to glaring contradictions. So Grandilevsky writes that according to legend, the descendants of the Kura (Kuru?) Were powerful people («representing an impressive force») and at the same time, speaking of the stone arrows, knives and axes found in the area of Arkhangelsk and Kholmogor, he concludes that Chud «had nothing but stone tools».

For us today, these stone tools testify to the fact that people («in the initial stage of development of Zavolotskaya Chud» — according to A. Grandilevsky) inhabited these lands as far back as the Stone Age, and the educated Orthodox priest in 1910 considered that: «Almost this helplessness (among the people whose neighbors didn’t dare to measure strength) developed for Zavolotskaya Chud that amazing trick about which all kinds of stories circulate among the masses, weren’t these needs prompted by a small tribe („spread — its limits throughout the Dvina from the lower reaches and ending with the Vaga River “) to live, straining her forces in the struggle for self-preservation, didn’t she temper their body in such a powerful nature that among the people they are now amazed at the stories about the heroic strength of Zavolotskaya Chud, and these stories, it must be assumed, have some truth».

And further: «… traditions point to the heroic growth and strength of the ancient Chud and attribute to it the ability to talk to each other at enormous distances; from Kurostrov to Matigory, to Ukht-ostrov, and from there to Chukhchenemu.»

We must pay tribute to A. Grandilevsky, he was somewhat puzzled by the fact that the description of the heroic appearance of Chud did not match what he saw among the Kholmogory peasants — «eyes are dark brown, hair is black, sometimes like tar, dark complexion and usually low growth». One can agree with him that «the Finnish origin of the Chudian tribes does not speak at all in favor of powerful growth,» but it is difficult to imagine that «Chud Zavolotskaya herself could fall as an accidental exception, in special conditions that, however, were not included into a positive law for posterity».

Indeed, the progress of the early Iron Age, when in the second half of 1 thousand BC the climate of the North of Eastern Europe changed dramatically and dark-coniferous taiga and tundra are replacing broad-leaved and mixed forests, the composition of the population has somewhat changed, and aliens from the Urals, Finno-Ugric tribes, are more actively involved in the process of ethnogenesis.

But you can’t say that in the Russian North (and especially among the Pomors) the same type of «lotus-blue-eyed, reed-haired, light-bearded» warriors sung by the «Mahabharata» or «golden-haired, blue-eyed arimasp of the ancient Greeks is so rare that it is so close to the descriptions of the mighty» white-eyed «Chud Zavolotskaya Russian chronicles and folk traditions. «Chud» (chudnyy, chudesnyy, chudo -miraculous, wonderful, miracle) — nothing in this name speaks of the Finno-Ugric affiliation of this people, it only indicates that it caused surprise among its neighbors, seemed to them «miraculous» or «miraculous» -«chudesnym» or «chudnym».

A. Grandilevsky writes further: «The mental power of the prehistoric Chud is not directly indicated in popular rumor, for it can already be said more thoroughly than the legends that Zavolotskaya Chud initially claimed to be human idol sacrifices, ferocious cruelty to enemies, inability to invent more the best adaptations for domestic life and work, but on the other hand it’s nowhere to be seen that she had a sympathy for wandering life, or did not allow open relations with other peoples, or had the inclinations to quickly assimilate the beginnings of cultures, is not visible in it «conquest, but there is evidence hinting at her particular desire for better public amenities, which later gave her extreme stability and widespread fame.»

The Kurostrovsky sleeve of the Dvina at the Kur village is known, at Kholmogor — Kuropolka. In the old days, the posad itself and the hillfort Kholmogor was called Kuropol. In the 19th century he was considered miraculous.

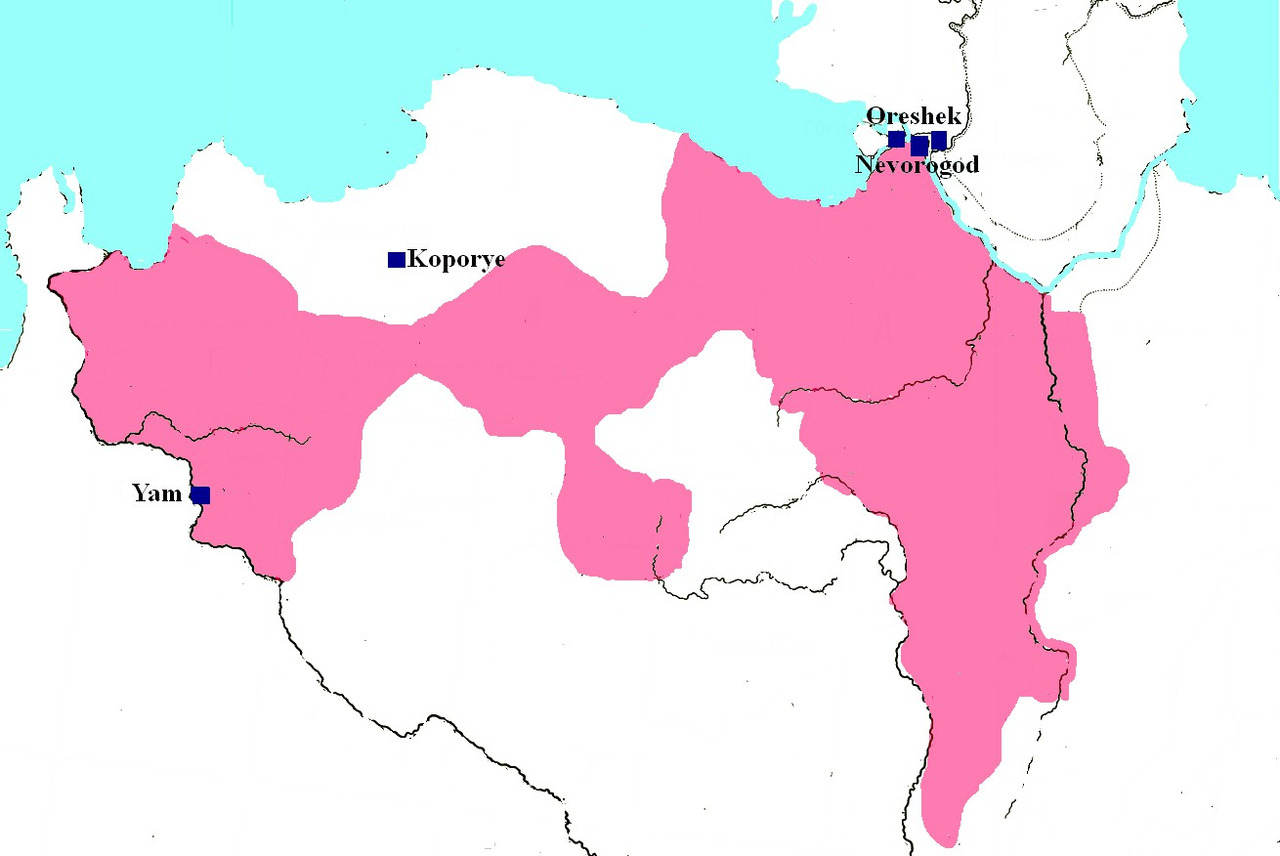

Richard James, in the early 17th century, recorded that in Kholmogory «Chud lived before, and she spoke a language different from the language of the Lapps and Samoyeds, but now she is no longer there.»

According to the calculation of 1850, there was no Chud in the Arkhangelsk province, although 25 Gypsies, 1186 Germans and 570 Jews were noted.

According to the lists of settlements of the Arkhangelsk province in 1861 (information from parish lists), Chud lived with Russians in Arkhangelsk, Kholmogorsky and Pinezh counties.

In the Arkhangelsk district in the villages — Bobrovskaya (Bobrovo), Yemel’yanovskaya (Arkhangel’sko), Stepanovskaya (Kumovskaya, Kukoma), Savinskaya (Zarechka), Tsinovetskaya (Tsenovets), Filimonovskaya (Abramovshina), Uvarovskaya (Uarovskaya), Samyshevskaya (Boloto), Petrushevskaya (Peshkovo), Durasovskaya 1 (Mal’gina Gora) and Durasovskaya 2, Chukharevskaya (Chukarenskaya), Kondrat’yevskaya, Aleksandrovskaya, Yeletsovskaya, Ust’lyyadovskoye (Amosovo), Nefed’yevskaya, Burmachevskaya, Olodovskaya (Gorka), Mitrofanovskaya, Chukhchinskaya, Patrak’yevskaya, Ivaylovskaya.

In Kholmogorsky district in villages — Annina Gora (Vavchugskaya, Belaya Gora), Rogachevskaya (Surovo), Tikhanovskaya (Tikhnovskoye, Shubino), Matveyevskaya (Neverovo), Marikovskaya (Marilov Pogost), Perkhurovskaya (Pergurovskaya, Shagino), Petrovskaya (Petrovo), Danilovskaya (Churkino), Kosnovskaya (Puginy), Trekhnovskaya (Kuchin navolok), Boyarskaya, Andriyanovskaya (Tyshkunovo), Verkhnemategorskom-Yemetskom, Shil’tsova (Shal’tsova), Kozhevskaya gora (Kozhina Gora), Khvosty, Korchovskaya, Yursobitskaya, Goroncharovskaya (Goroncharovo), Sukhareva, Zapol’ye, Oseredskaya, Andreyanovskaya, Bereznik, Zaozerskaya, Filippovskaya, Perdunovskaya (Chasovenskaya-Kuznetsovka), Karzevskaya, Terebikha, Oshchepova (Yakimovskaya), Gorka (Zinov’yevskaya), Terent’yeva, Nizhniy Konets (Polumovskaya), Brosachevskaya (Brosachikha), Kul’minovskaya, Kyazmezhskaya (Kyazlish) (along the rivers Boyar-Kurya, Kurostrovka, Emtsa, Dvina, Vaimuga, Lake Kulmino).

In Pinezhsky County, a Chud place with Russians was in the villages of Verkhnekonskaya and Valtegorskaya (Valteva) (along the rivers Nemnyuga, Ezhuge and Pinega).

Belorussians (in the Vologda province they were considered Chud) were counted in the Kholmogorsky district in the villages of Tovra, Voronovskaya, Derevenka, Nizhny Orlets, Upper Orlets, Kuryanoga, Ichkovskaya, (Shatikha) Stupino, Panilovskoye, Vlasyevskaya, Novinskaya, Gorsko-Kuznev Vysokiy Bor, Kozminskaya, Chasovenskaya, Eliseevskaya, Kashinskaya, Velikodvorskaya, Andriyanovskaya (along the rivers Dvina, Ukhtoostrovka, Yemets).

Purely Chud villages were considered Antsiferovskaya, Vakhromeevskaya, Expense (Khodchegory), Berezninskaya, Obukhovskaya, Nizhnematigorsk (Borisoglebsk, Demidov), Demidov (Pogost), Tyumshenskaya 1 (Tyushmenevskaya, Davydovskaya) and Tyumshenskaya 2 (Belogorsky) in Kholmogorsky district along the Boyar-Kurya river. Even then, they paid attention to the fact that the areas inhabited only by Chud bore exclusively Russian names.

In the Shenkur Uyezd, the Chud villages were not distinguished, and in the 14th century its entire territory with Verkhovazhy was considered the Chud country. Chud in Shenkursk was taken into account until the 16th century.

It should be noted that Chud stood out together with migrants from Novgorod, in areas where they were not, instead of Chud, Russians were indicated. In Arkhangelsk Chud considered the Russian Old Believers.

The list of populated areas of the Vologda province in 1859 indicates the presence of Chud as an ethnic group in the province, different from the Russians and Komi-Zyryans. Although the metropolitan scholars considered her Finns, and in the parish lists — Belarusians.

According to the parish lists, Chud was available in Nikolsky, Solvychegodsky and Ustsysolsky counties in neighboring areas in 62 villages (4234 people).

In Nikolsky Uyezd (1630 people) — Vymol, Lychenitsa, Pogudino, Hay, Kurilovo, Alferova Gora, Myateneeva Gora, Zavachug, Sushniki, Kayuk, Kobylino-Ilyinskoe, Spitsino, Ploskaya, Kobylkino, Navolok, Gorka, Gorbunovskaya, Pavlovo, Zavrazhe, Manshino (along the rivers Sherduga, Zhydovatka, Birch, Zavachuga, Ishenga, Kokoshikha, Imzyuga, Yug).

In Solvychegodsky Uyezd (2938 people) — Astafyeva Gora, Fire, Zmanovsky fix (Zmanovo), Mishutino, Leunino, Eremina Gora (Okolotok), Lisya Gora, Kuryanovo, Yaruny (Yartsevo), Goncharovo (Gondyukhiny), Mishutino Verkh (Gusikha), Potanin fixes (Prison), Pozdeev mends (Omelyanikha), Golaya gorka, Byk, Goryachevo, Konishchevo, Vyatkina Gora, Verkholalsky churchyard, Knyazha, Stroikovo, Popova exhibition (Pupok), Tokarevo Zholtikovo, Pryanovskaya (Byzov), Vasilyevskaya, Frolovskaya (Zuikha), Tregubovskaya, Varzaksa, Novikovskaya (Kuliga), Grishanovskaya (Balushkins), Rychkovo, Konstantinovskaya (Fedyakovo), Fedyakovo, Teshilova Gora (Kushikha), Novoselova Gora (Novoselka), Kochurinskaya (Zaruchevye), Grigoryevskaya (Kalinino), Gorka, Makarovskaya (Komarovo), Ustye, Selivanovskaya (Isakovs), Nechaevskaya (Mezhnik), Ryabovo, Koneshevskaya (Butoryana), Sludka, Deshlevskaya (Koshary), Matyukovskaya (Balashovs), Chernyshevskaya (Artemyevshina), Prilitsa, Zadorikha, Bereznik (along the rivers Lala, Varzoksov, Torzov, Tornov, Chakulka, Mezhnik, Hearth, Dorovitsa, Vychegda).

In Ustysysolsky Uyezd (749 people) — Mishinskaya (Podkiberye), Spirinskaya (Zanyule), Rakinskaya (Bor), Shilovskaya (Zarodovo), Garevskaya (Trofimovskaya), Bor-Nadbolotomskaya (Keros), Urnyshevskaya (Verkhnyy Konets), Matveyevskaya (Spas Porub), Karpovskaya (Gavrilova), Kulizhskaya (Chinicheva), Raevskaya (Ostashevskaya), Podsosnovskaya (Lobanova), Nelitsovskaya (Shmotina), Trofimovskaya (Poryasyanova) (along the Nevlyora, Luza, Nyula,, Porub, Buba).

In Kargopol County in 1316, along the Lekshmozero (Chelmogora), 53 km. from Kargopol there was a Chud population. In 1349, the Roman Lazarus noted the presence of Chud and Lopi at the Murmansk monastery in Obonezhie.

According to the information of 1873, in the Olonets province, Chud was considered — 26172 people (Chud russified — 7699 people). Apart from them, Finns were counted — 3,775 people, Lapps — 3,882 people, Karelians — 48,568 people.

Chud was located in Lodeinopolsky district (7447 people), Olonets district (1705 people), Vytegorsky district (6701 people), and Petrozavodsk district (10319 people).

The name Chud was attributed to this ethnos, according to Academician Shegren (1832), who indicated that, he lived in Belozersky and Tikhvin districts of the Novgorod province, where the Russians called them Chud, and the Vepsians themselves called themselves Zjudi. However, Novgorodians also identified Kolbyagi (Tikhvin) and Varangians (Ilmen).

Why St. Petersburg scholars have decided that the ид Zhidi’, who called themselves «Ljudi,» are Chud, and for example, not the descendants of the Novgorod ующих Judaizers’, it is not clear. Most likely, an error has occurred. The handwritten L looks like a handwritten capital letter Z, when publishing the manuscript in German, it was read as Z, and then when re-publishing Shegren’s work in Russian, and they read the name of the people as Chud. And under the authority of the academician, who did not write this at all, they began to call the Veps-Ludikov — Chud. After 1920, these people began to be called by self-designation of the greater part of the Vepsians, and then, they were recorded in a large part in Karelians.

Chud Russified lived separately from the rest of the Olonets Chud (Vepsians) in the east in Vytegorsky uyezd on the border with Kirillovsky and Kargopolsky uyezds.The population of these places does not belong to the Vepsians Russified by any of ethnographers.

She lived Chud Russified in 118 villages of Vytegra district: Pesok, Venyukova, Vasil’yevskaya (Ishukova), Bobrova, Nikiforova, Zaparina, Ukhotskiy pogost (Il’ina), Klimovskaya (Tobolkina), Yefremova, Popad’ina, Niz, Mechevskaya, Yeremina, Leont’yeva, Yershova, Okulova, Bryukhova, Kobylina, Prokop’yeva, Yermolina, Pankratova, Kopytova, Mishutkina, Kozulina, Vasil’yeva, Moseyevskaya (Chernitsina), Poganina, Yurgina (Yurkina), Ambrosova (Obrosova), Sergeyeva, Saustova, Likhaya Shalga (Shalga) (on the river Ukhta);

Surminskaya (Teryushina), Yemel’yanovskaya (Sharapova), Patrovskaya, Filosovskaya, Ignatovskaya (Shil’kova), Demidovskaya (Zapol’ye), Duplevskaya (Zapol’ye), Yermakovskaya (Zapol’ye), Budrinskaya (Kromina), Prokopinskoye, Antipinskaya (Gorka), Grigor’yevskaya (Novoselova), Tikhmangskiy Pogost (Danilovo), Vakhrusheva, Vakhrusheva, Palovskiy Pogost (Dudino), Aksenova, Klepikova, Fat’yanova, Fedorova, Burtsova, Demina, Rukina, Novoye selo, Trofimovskaya (Chasovina), Oryushinskaya (Vydrina), Murkhonskaya, Lavrovskaya (Petunina), Dmitrovskaya (Tsanina), Fedotovskaya (Pavshevo), Feofilatovskaya (Rubyshino), Ryabovskaya (Simanova), Mininskaya (Berezhnaya), Kirshevskaya (Kruganova), Dalmatovskaya (Savina), Tretiakovskaya (Manylova), Mukhlovskaya (Knigina), Fertinskaya (Vaneva), Koshkarevskaya (Filina), Iarakhivskaya (Parakeyevna, Slasnikova), Sidorovskaya (Davydova), Yeltomovskaya (Verkhov’ye), Mikhalevskoye (Vypolzovo), Guyevskaya (Fokino), Manuylovskaya, Zheleznikovskaya (Gurino), Kashinskaya (Verkhov’ye), Kuromskaya (Konets), Gorlovskaya (Mal’kova), Il’inskaya sloboda (along the Tikhmang River);

Antonovskaya (Baranova), Mokiyevskaya (Rusanova), Murav’yevskaya, Gorbunovskaya (Pustyn’), Fominskaya (Gorka), Fedos’yevskaya (Matyushina), Kuznetsovskaya (Kirilovshchina), Kachalovskaya (Privalova), Vershininskaya pustosh’ (Vershinina), Isakovskaya pustosh’, Lukinskaya (Povinki), Aleksinskaya (Gurino), Davydovskaya (Maksimova) (along the river Shalgas); Perkhina (Antipina), Pashinskaya (Beregovskaya), Antipina (Antipa, Perkhina, Malaya Kher’ka), Fedorovskaya (Khaluy), Antsiferova (Khaluy) (along the Indomanca River);

Lebyazh’ya pustosh’ (by the Desert Creek);

Deminskaya (Dubininskaya), Matveyevskaya (Procheva) (by Shey-brook); Falkova (at Ukhtozer);

Antsiferovskaya (Bereznik, Khaluy), Krechetova (Pankratova), Agafonovskaya (Bol’shaya), Rakovskaya (Ugol’) (at Antsiferovsk lake); Borisova Gora (Gora), Mitina, Pankratovo (Matveyevo, Isayevo), Ivanova (Kir’yanova), Blinova (Gorka), Yelinskaya (Kropacheva, Novozhilova, Yermolinskaya) (at Isaevsk lake);

Antsiferovskaya (Anan’ina, Puzhmozero), Yermolino (Novozhilovo) (at Pujmozero).

In the 19th century, scientists called indiscriminately the peoples of the Perm group and the Vod, and the Chukhons, and the Karelians, and the Estonians, although talking about the mono-ethnic composition of the population of Estonia in the 19th century doesn’t make sense. The merger of several nationalities into one Estonian people and their assimilation of other ethnic groups (including Slavic Krivichs and Germanic Danes) were not yet completed. Therefore, it can be assumed that the name of the miracle was given to the Finno-nized part of the local population by Novgorodians, in other places the presence of the Finno-Ugric population was not recorded.

The list of populated places of the St. Petersburg province of 1864 was attributed to Chud, based on the opinion of scientists, whose name (vatiya-lyset) was derived from the word «waddy», the meaning of which is not known in Finnish. The people are closer to Estonians than Karelians. Vod lived in Peterhof, Yamburg counties. Moreover, in the parish lists, part of its settlements is called Izhora.

In addition, Chud named part of the settlements lying in the Russian regions along the Luga River — Pulkovo, Sola (Sala), Nadezhdina (Blekigof), Mariengof, Koshkino, Zakhonye, Sveisko, Zhabino, Kalmotka, Verino (Nikolaevo), Kuzmino, Yurkino, Kepi, Gorka, Podoga, Lutsk, Lutsk, Mikhailovskaya, Novopyatnitskoe.

Official statistics, according to the census of 1897, separated the vody and ests from chud. In addition to vod and estonians, 303 people spoke miracle languages in the Yamburg district. The Vepsians were not there.

In 1535 the population of Toldozhsky, Izhersky, Dudrovsky, Zamoshsky, Egorievsky, and Opoletsky, Kipensky, and Zaretsky pogosts was referred to Chud in the Novgorod lands.

Given the relocation from Finland, Estonia and Livonia in the 17th century, as well as the massive population decline at the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 18th century can be assumed assimilation by local settlers.

The Sami, who knew the chud well, did not mix them with the Karelians.

According to the legends of the Karelians and Sami, Chud — «murderous murderers», every summer came from the mountains and killed many people. Sami «Chute, Chud» — «pursuer, robber, enemy.» In the traditions of the Sami, it is indicated that in ancient times, the White-eyed Chud came to their lands. She wore iron armor over her clothes, and iron horned helmets on her heads. Faces were covered with iron nets. The enemies were terrible; everyone was slaughtered in a row. A similar form of the Scandinavian Vikings took place only from the 13th century.

The Finno-Ugric peoples them selves always talked about Chud as about some other people. Komi-Zyryans and Permyaks distinguished themselves from the «real Chud.» The reason is in the neighborhood, they knew Chud. For Komi-Permyaks and Udmurts — Chud is an ethnic group completely alien to them in language, which, like Novgorodians and Vyatchians, took part in tribal strife and war.

The Vyatka chronicler mentioned the peoples of Chud and Ostyaks on Chepets. According to legend, Chuds fortifications were located in these places, and it is here that bronze objects, united by the name Perm Animal Style, are found. Experts have always recognized the Iranian influence on the art of the Perm animal style.

Descriptions of the Komi indicate an unusually large growth of representatives of the Miracle. In addition to the Chud-giants, the Komi-Permyaks distinguish another people of small stature — Chudov.

Traditions about Chyud are associated with legends about the people of Sirte (Sihirta, Sirchi), who lived in the tundra before the arrival of the Nenets. According to legend, the syrts were small in stature, they said, slightly stuttering, wore beautiful clothes with metal pendants. They had white eyes. The houses of Sihirt were high sand hills; they rode dogs and grazed mammoths. Like Chud, Sirte were considered skilled blacksmiths and good warriors. There are references to military clashes between the Nenets and Sihirt. There are known cases of the marriage of the Nenets to women of Sihirt. The Nenets distinguished sikhirt from themselves, Khanty and Komi.

Academician I. Lepekhin wrote in 1805: «All Samoyed land in the Mezen district is filled with desolate dwellings of the once ancient people. They are found in many places: by lakes, on the tundra, in forests, in rivers, made in mountains and hills like caves with «holes like doors. In these caves they find furnaces and find debris in iron, copper and clay household items.»

For the first time, the Nenets legends about the Sihirt, who spoke a language different from the Nenets, were recorded by A. Schrenk in 1837 in the Bolshezemelskaya tundra. The Nenets were convinced that the last syrtes even 5 generations before the 19th century (17—18th century) met on the Yamal Peninsula, and then finally disappeared.

They assume the original meaning of the word Chud — «Germans», from the Gothic «Tsiud» — «people». But the Thiudos is mentioned among other peoples affiliated with the Gothic power of the 4th century and therefore not German. The Jordan wrote: «Germanarich, the noblest of the Amals, who conquered many very warlike northern tribes and made them obey their laws. Many ancient writers compared him with dignity to Alexander the Great. He conquered the tribes: Golthescytha, Thiudos, Inaunxis, Vasinabroncas, Merens, Mordens, Imnisscaris, Rogas, Tadzans, Athaul, Navego, Bubegenas, and Coldas».

Chud is used in the Mahabharata as the name of the Chedi people. In the Puranas, the Kurus, Chedyas peoples are indicated next to Vatsa and Kauravyas.

In Pomorie (in Kemi), it was believed that Chud had a red skin color and went to Novaya Zemlya. It is appropriate to recall that the inhabitants of ancient Egypt (the country of Lower Kemi) considered themselves red-skinned immigrants from the country of Upper Kemi.

Thus, from the legends, traditions, and beliefs that remained in the Russian North right up to the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, an image of a people grows up — a powerful, rich, independent, distinguished by a strong physique, possessing sacred knowledge and amazing abilities. The name of this people is Chud Zavolotskaya. But since the legendary «White-eyed Chud» lived primordially on the lands where the Scandinavian sagas placed the country of Biarmia and the fabulously wealthy warlike Bjarmas, it remains to draw a logical conclusion: Chud Zavolotskaya and Bjarma are one and the same.

And if we go even deeper downward, then next to the names «Chud» and «biarma» there will be «Unna-Huns (Huns)», «Alano-Russes», and «Rusolans», «Cimmerians», «Sarmatians», «Scythians-Rus», «Arimasp», «Issedon», «Hyperborea», Aryans -" Northern Kourou», etc. All of them lived on the shores of the White (Milky) Sea, where, according to the texts of the Rigveda, the gods churned the ocean to get the drink of immortality «amrita».

Archaic Slavic ethno and hydronymy and the problem of the Slavization of the Russian North

Ethnographers and historians have different opinions about the time of settling of the Finno-Ugrians in the North. If we are talking about a specific Finnish or Ugric ethnic group, then its settlement in the modern territory dates back to the 5th century (Livs), 10th century (Finns), 15th century (Nenets). If we speak of an abstract Finno-Ugric ethnos, then its settlement is attributed to the 3rd-2nd millennium BC. Slavic settlement in the Russian North is shifted by most historians to the 9—12 centuries. To reconcile positions, a version of the presence of an ancient Vepsian substrate, which is reflected in the legends about Chudi, and its determining influence on the ethnogenesis of the Russian North, is put forward. (Pimenov V. V. Veps: an essay on ethnic history and genesis of culture. M. L. Science. 1965).

Russian North do not have a reliable etymology. So the name of the river Vologda is formed from the supposedly existing Finnish term «valgada» — «white», but in the Finnish names there must be a geographical term to which the definition refers.

Onega — the name of the river is explained from the Finnish «enoyogi» — «rapid flow». But how to explain the name of Lake Onego, from which the river is believed to have got its name. Pinega, the right tributary of the Northern Dvina, is 800 kilometers long. Since the 19th century, the name is explained from the Finnish «pienga» — «small river». Such examples could be greatly expanded. The use of the Finno-Ugric concept by historians and ethnographers leads to curiosities when they try to find Finno-Ugric interpretations of names for rivers that have different, from Russian, independent names in the Finno-Ugric languages (for example, Vychegda — Ezhva).

On the other hand, when analyzing toponyms in the central regions of the North, for example, in the Tarnogsky district of the Vologda region, out of settlements, large and small, only 6 have non-Russian names (MAIKTS 6.1985).

This allows us to say that the contribution of the Finno-Ugric substratum population to the ethnogenesis of this territory was extremely insignificant, if any.

Moreover, a wave of migration of the Finno-Ugrians from the borders of the Swedish kingdom to the territory of the Russian state in the 17th century was recorded.

The inconsistency of the data, it would seem, does not make it possible to determine the presence or absence of the Slavic (or, more precisely, the North Russian) population in the era preceding Kievan Rus.

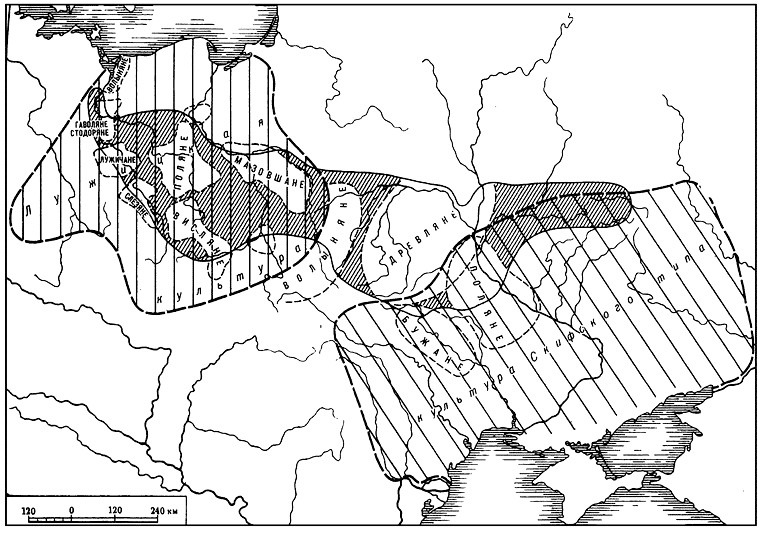

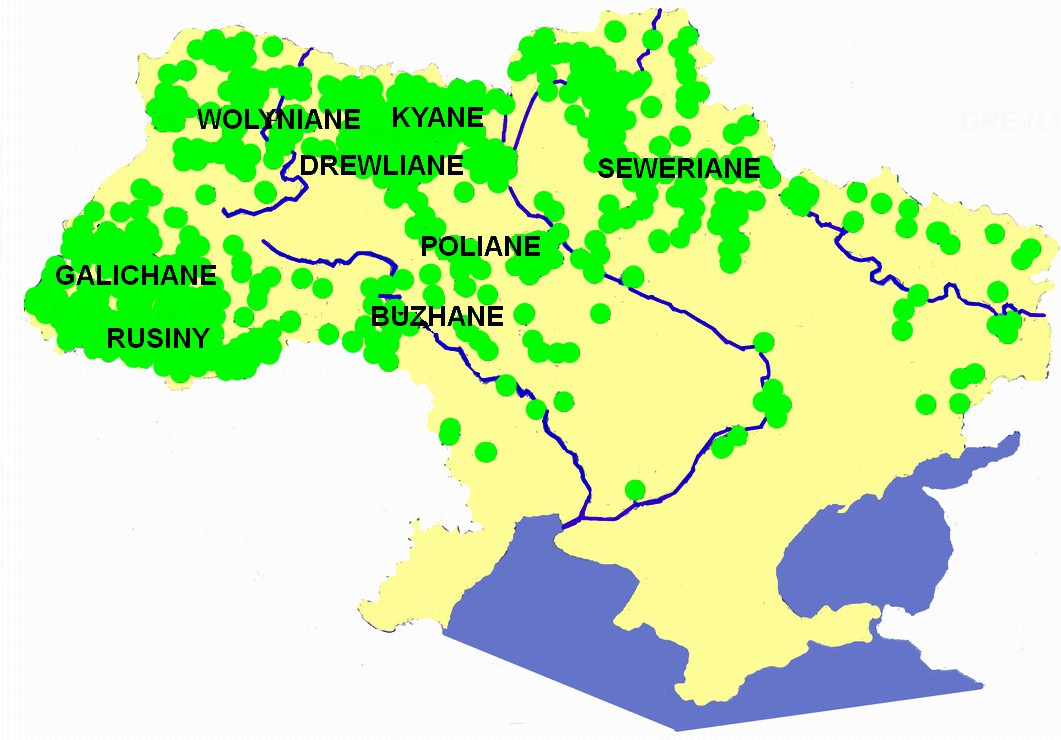

However, modern science has found indicators of the course of ethnic processes. So Academician B. A. Rybakov showed the connection between the ethnonyms of the Slavic tribes with the time of their formation. «The division of tribal names into original and acquired in the process of later colonization allows us to link the issue of their dating with the determination of the time of the beginning of colonization.» (Rybakov B. A. Kievan Rus and Russian principalities of the XII — XIII centuries. M. Science. 1982). He writes: «Of particular importance is the determination of the time of the formation of tribal alliances. Nestor, describing the ancient history of the Slavs, uses only the names of tribal unions, not denoting small tribes anywhere, but this does not determine the initial date of the formation of unions. However, an analysis of Nestor’s text can provide an answer to the question of interest to us. Until now, no attention has been paid to the fact that the names of peoples in Nestor are mainly divided into two groups: some names end in "-an» or "-yan» (polyane, mazovshane, etc.) and, possibly, come from certain toponyms, and others are in "-ichi» or "-tsi» and have a clearly patronymic coloration (radimichi, vyatichi). The terminology of West Slavic sources agrees with this.

The main thing is that when both groups are plotted on the map, an interesting pattern emerges: the groups form two zones — an inner zone and an outer zone that covers it from all sides.

The inner zone (names like «polyane») coincides with the area of settlement of the Slavs in the Scythian-Skolot time, and the outer zone (names like «radimichi») — with a wide area of later colonization. In the outer zone, there are tribal names formed according to both principles — both toponymic and patronymic, but we find patronymic only in the outer zone of colonization. The inner zone, which coincides mainly with the ancestral home of the Slavs, knows only names such as «polyane», «vyslyane» (three exceptions: sever, khorvats and dulebs) and does not know the names of the second type at all…

The patronymic form of the names of the tribal unions is confirmed in the legends recorded by Nestor: the Radimichi descend from a certain hero Radim, who brought them to Sozh «from the Lyakhes».

Thus, the main process of widespread settlement of the Pre-Slovens falls for the time after the existence of the Skolot unity. Therefore, the original, toponymic names of tribal unions (and the unions themselves, of course) can be dated to the first half or middle of the 1st millennium BC.

If archeology helped to clarify the boundaries of tribal unions for the time of their withering away (X — XII centuries AD), then it is quite natural to turn to archaeological data to determine the territories of tribal unions of the era of their inception.

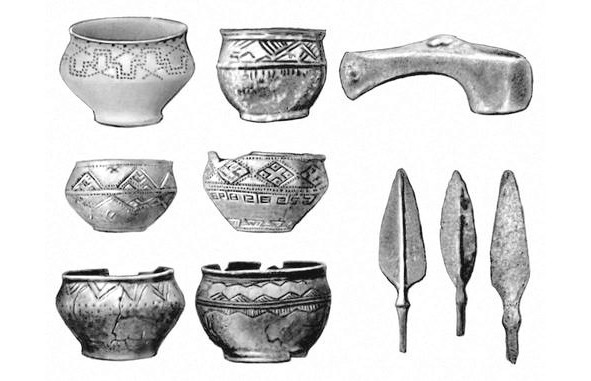

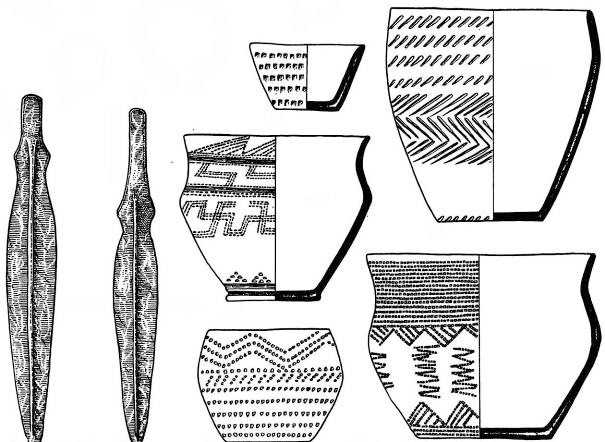

Considering the local variants of the Trzhinets-Komarov culture of the primary Proto-Slavs and comparing them with the location of the Slavic peoples (tribal unions) near Nestor, we find a number of geographical coincidences for the main tribal groups.

Moreover, attracting local variants of the Skolot-Lusatian archaeological sites of the 6th — 4th centuries BC, we will see the same picture: local variants of this era also correspond to the location of the Nesterov peoples and their list coincides with the list of variants of the Trzyniec culture… The stability of geographic groups over a whole millennium deserves attention. The names of the unions could change at different times.» (Rybakov B. A. Kievan Ruse and Russian principalities of the XII — XIII centuries. M. Science. 1982). (Note that the ethnonym «Severa» is known as «Severyane» (among the settlers to the Balkans), the Krivichi are also known as «Krivi» and «Kriviteni» (they include «Polochane» along the Polota River and «Smolyane»).

Speaking about the Slavic peoples (unions of tribes), B. A. Rybakov attributes their formation to two eras: he associates the names of the type «Radimichi» with the later colonization of the 6—7 centuries, and the names of the type «Polyane» with the Trinecko-Komarov culture.

«B. V. Gornung speaks even more definitely about the isolation of the Proto-Slavs in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC and directly connects the Proto-Slavs with the Trzhinetsk and Komarov (a more developed version of the Trzyniec) cultures.

The vast area of Trzyniecki culture in its final form again revived the idea of the Slavic massif from the Dnieper to the Oder, in full agreement with the latest linguistic data on the time of the separation of the Slavs…

Thus, we can recognize the area of the Trzhinets-Komarovo culture as the primary place of unification and formation of the first spun off of the Proto-Slavs, who remained in this space after the grandiose settlement of the Indo-Europeans — the «cords», calmed down. This area can be designated by the somewhat vague word «ancestral home»… Let us consider the duration of the historical life of each of the cultures, reflected by three maps: Trinecko-Komarovskaya — about 400 years, Przeworsko-Zarubinetskaya — about 400 years, Culture Prague-Korczak — about 200 years. As a result, we get about a thousand years, when the area of a certain ethnic community, reflected on these maps, was a historical reality. We involuntarily have to reckon with this and conform to this reality our research in the field of Slavic ethnogenesis.» (Rybakov B. A. Paganism of the Ancient Slavs. M. Science. 1981).

«The creation of a homogeneous archaeological (Trinecko-Komarov) culture was the result and material expression of the consolidation process. The Slavism of that time was not absolutely monolithic — a single archaeological culture was subdivided into 10—15 local variants that could correspond to ancient tribes or tribal alliances, and possibly to the primary dialects of the Proto-Slavic language (?).

The starting point of reference for the Slavic historical process that we have chosen is the middle of the 2nd millennium BC — finds the Proto-Slavic world at the level of the primitive communal system, but with a fairly rich historical past: the ancestors of the Slavs already from the V — III millennia BC knew agriculture, experienced a temporary rise in the Eneolithic era associated with the strengthening of pastoralism, took part in the settlement of huge spaces and by the time of the crystallization of the Proto-Slavic ethnic group, they had already reached a certain level of culture: their economy was based on settled cattle breeding and agriculture with hunting and fishing as supplements; they settled in small villages. The main tools were also made of stone, but bronze was also used (chisels, awls, ornaments). The separation of the druzhina stratum within the tribe is not documented.» (Rybakov B. A. Kievan Ruse and the Russian principalities of the XII — XIII centuries. M. Science. 1982).

Komarovskaya culture dates back to 1500—1200 BC or 16—8 century BC, the Zachinets culture dates back to the 15—12th century BC (Archeology of the USSR. The era of the bronze of the forest belt of the USSR. M. Science. 1987).

Let us now turn to the Russian North. We have such sources as «Stepennaya book» and «Biographies of Stephanie of Perm», which preserved the ethnonyms of the peoples who lived here in the 14th century.

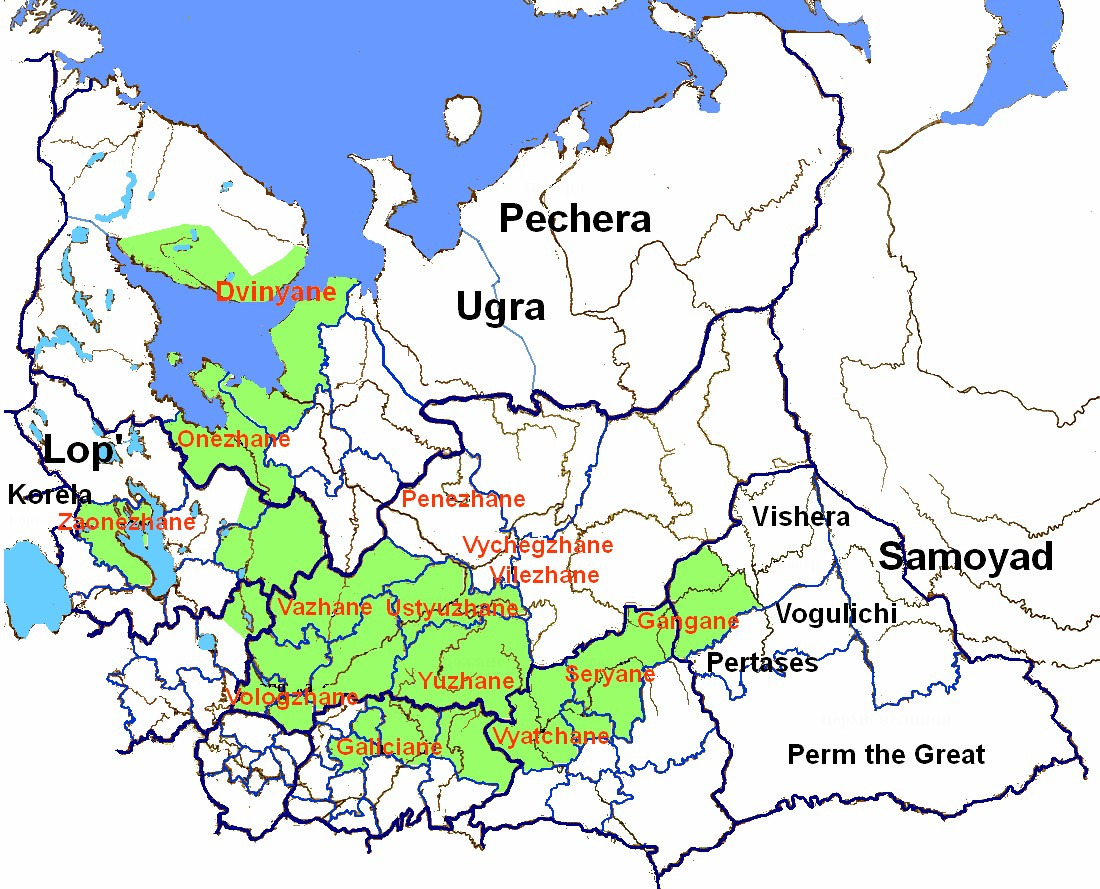

So «Stepennaya book» in the «13th degree» calls: «These are the names of foreign-language countries and places living near Perm: Dvinyane, Ustyuzhane, Vilezhane, Vychegzhane, Penezhane, Yuzhane, Seriane, Gangane, Vyatchane, Lop, Korela, Yugra, Pechera, Vogulichi, Samoyad, Pertasy, Great Perm, Gamal, Chyusovaya.»

«Biography of Stephanie of Permsky» reports: «The names of places and countries and lands of foreign languages living in Perm and around Perm: Dvinyane, Ustyuzhane, Vilezhane, Pinegzhaen, Yugzhane, Syryane (Seriane), Gainiane (Gayane, Guyane), Vyatchane, Lop, Korela, Yugra, Vishera, Pechera, Vogulichi (Vogulitsy, Gogulichi), Samoyad, Pertasy, Great Perm the verb Chusovaya (Михайлов М. Описание Усть-Выма. Вологда.1851).

Let us note the identity of these two lists, in which the Ustyuzhans, the Dvinyans, and the inhabitants of Pechora, and the people of the «Gangan» or «Gainyans» in the upper reaches of the Kama River are named among the peoples foreign to Stephen of Perm.

Some authors believe that the Lop lived along the Lopve River, a tributary of the Kos, or in the Slobodsky district near the village of Lopari. Rivers named Lop-yu, Lop-va are found in the Northern Urals. But the lobe is indicated adjacent to the core. Korel in the 14th century is placed on the Karelian Isthmus and in the adjacent part of Finland (Vyborg province). Near them, in Zaonezhie, back in the 17th century, there were Lop churchyards. Karelians are unknown in Perm. And Pertas will be stirred up in the south of the Komi-Permyak district.

Note that not only Voguli and Korela, but also Dvinyans, Ustyuzhans, Vilezhans, Vychegzhans, Penezhans, Southerners, Vyatchans, who are now considered Russians, are classified as «foreign-speaking countries and places». In a number of lists the Gangan (Gainyan) is replaced by the Galicians. Alexander Gvagnini in 1581 in Verona wrote about the Ustyug region «they have their own language, although they use Russian more» (Известия Архангельского общества изучения Русского Севера. Архангельск. №1. 1911).

Perhaps in the 14th century, separate, independent Slavic languages existed in these lands. V. I. Dal wrote: «The speaking of the Vyatchan people first advised me about the origin of the Bulgarian consecutive member, which, having produced it from Greek; particles „ot, at, to, ta, te“ are applied on Vyatka not indifferently, but by kind…» (Даль В. И. Толковый словарь живого великорусского языка. Т. I — IV. М. 1978. p.LVIII). Either the North Russian dialects sounded alien to the author of the text.