Бесплатный фрагмент - Chess. A modern textbook

Introduction

CHESS… It’s a whole world for me, and a single game is a small model of our life.

What are the benefits of chess? What does chess offer to modern people?

“Chess is life in miniature. Chess is a struggle, chess is a battle.”

Chess is a game, but it reflects a person’s essence like a mirror. His views on life, decision-making, emotional or precise calculation, plans, a person’s character, laziness or work capacity, emotional outbursts or cold restraint, imagination and the ability to correctly assess a situation, etc.

People have been playing chess for thousands of years, and even with the advent of computers, the attitude towards the game has not changed, which speaks volumes.

So, what does chess offer for a person’s daily life?

1. Independence in decision-making.

2. Understanding what the consequences of this decision will be.

3. The ability to assess the situation independently and make an appropriate plan of action.

4. They train the will and make our brain find the best way out of a critical situation, and in a very short period of time.

5. They train memory.

6. They develop the will to achieve a goal.

7. They teach a person to find the necessary information (the flow of information has increased many times not only in everyday life, but also in chess) and

apply it to the best advantage for themselves.

8. They teach you to control your emotions, thereby allowing you to focus on the task at hand.

9. They teach you to draw conclusions not only from the entire chess game, but also from each individual move.

These points apply equally to both life and chess, but there is one significant difference:

10. Life is unique and cannot be changed.

However, a chess game can be played again and again, allowing you to correct your mistakes and avoid making new ones.

Thus, the path of chess improvement is endless.

This is why I love chess, and I hope you will too…

Chapter 1—3: the initial level from the rules of the game to the 3rd level.

Chapter 4—7: from the 3rd to the 1st category

Chapter 8: from 1st to KMS inclusive

Chapter 8: modern vision of chess and recommendations for further study of chess

Chess is not just a game; it is an art of strategic thinking, an intellectual battle that captivates millions of people around the world. Over the centuries, chess has become an integral part of culture and education, promoting the development of logical, spatial, and analytical thinking. In this textbook, we aim to guide you on a fascinating journey of learning chess, from the basics to modern approaches to mastering this magnificent game.

The textbook consists of eight chapters, each designed for a specific level of chess player.

The first is the third chapter. In them, we will look at the basic rules of the game, the main positions and the beginnings that will help you master chess and reach the level of the 3rd category. Here we will get acquainted with the typical strategies, tactics and principles that are the basis of the game.

The fourth — seventh chapter. In them, we will dive into a deeper study of the game, moving from the 3rd level to the 1st level. We will focus on developing chess thinking, teaching various openings, positional games, and planning techniques. This chapter will help you to strengthen your skills and confidence at the chessboard.

Chapter 8 This is the basic knowledge from 1st category to Candidate Master of Sports (KMS). We will focus on the more complex aspects of the game (the basics of strategy), studying and analyzing the games of great chess players and analyzing mistakes. This will be a great opportunity to improve your level of play and make the transition to a higher knowledge of chess.

Epilogue

These are recommendations for further self-improvement. In the era of digital technology, chess has become more accessible than ever, and these recommendations will help you understand how to further enhance your skills.

By following this tutorial, you will discover a world of chess that not only develops your mind but also brings you joy. I hope that this book will be useful to you at every stage of your chess journey. Let’s embark on a new adventure of chess mastery!

Chapter 1

1.2 Chess terms: white and black squares, horizontal, vertical, diagonal, center, correct arrangement of pieces in the starting position (“the queen likes its color”), white and black pieces, moves of pieces, capture. Value of pieces

1.3 FIDE rules of the game, move 1.4 Attack on a piece, check, checkmate, stalemate, draw 1.5 FIDE rules of the game, partners

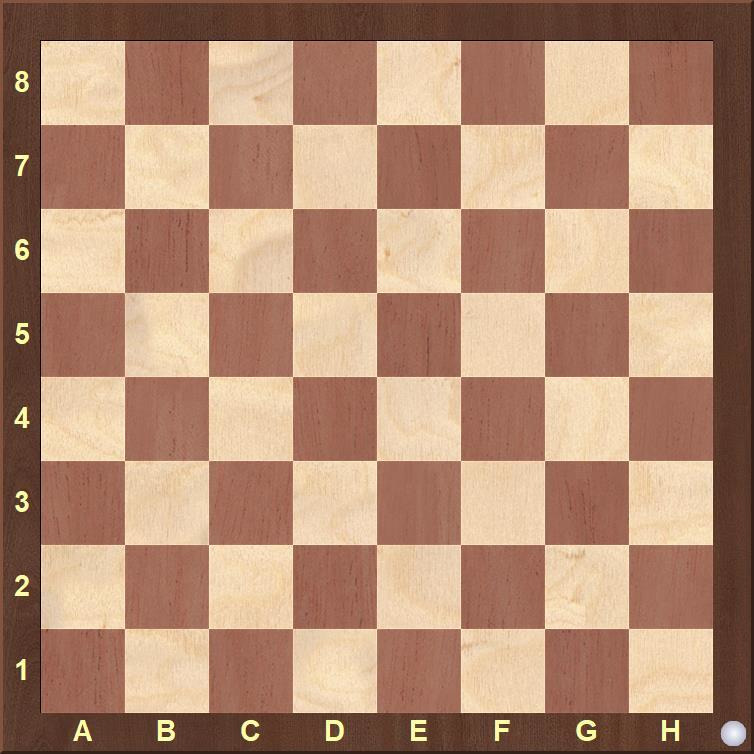

1.1 Chessboard

Chessboard Description

A chessboard is the surface on which a chess game is played. It consists of 64 squares (8x8), 32 light squares and 32 dark squares (in reality, the colors of the squares can be any combination).

Square Identification (Notation):

There are 64 squares or fields on the board.

Squares on a chessboard are conventionally called fields.

Fields are referred to as white and black, although in reality they might be different colors (e.g., light squares could be white, yellow, beige, etc., and dark squares could be brown, gray, green, or even red).

However, according to standard rules, light-colored squares should be called white squares, and dark-colored squares should be called black squares.

The squares are arranged in rows. There are 8 rows in total. Each row contains eight squares.

Rows of squares are called ranks. Similarly, there are files — there are also 8 of these.

Each row (rank) has its own number: from 1 to 8. Files are designated by Latin letters: from a to h.

You’ve likely noticed that the board resembles a coordinate system. That’s exactly right. However, instead of naming the axes, each square has its own unique name (e.g., e4, a1, h8).

Three types of lines on a chessboard:

File (vertical line),

Rank (horizontal line),

Diagonal.

Key Terminology Used:

Chessboard: Standard term.

Squares/Fields: Used interchangeably, though “squares” is most common.

Light squares / White squares: Emphasizes the conventional naming.

Dark squares / Black squares: Emphasizes the conventional naming.

Rows: Clarified to be ranks.

Columns: Clarified to be files.

Ranks 1—8, Files a-h: Standard algebraic notation.

Lines: Files (vertical), Ranks (horizontal), Diagonals.

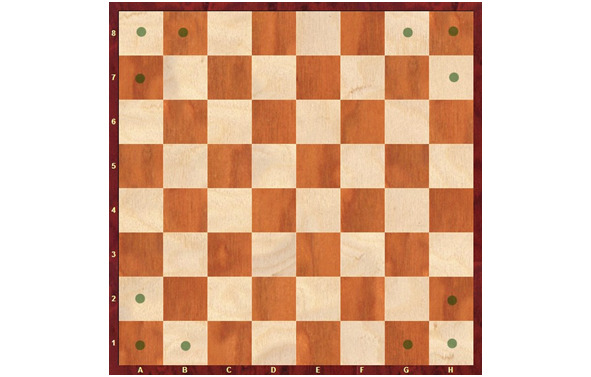

Flank The King’s Flank is the flank closest to the king at the beginning of a chess game, on the f, g, and h verticals. (red color on the diagram)

The Queen’s Flank is the flank closest to the queen at the beginning of a chess game, on the a, b, and c verticals. (green color on the diagram)

The horizontal cells are denoted by Latin letters from a to h from the Queen’s Flank to the King’s Flank, while the vertical cells are numbered from 1 to 8 from white to black. For example, in the initial setup, the white king is on the e1 square.

The book will use diagrams to represent the chess pieces, as follows, with their names in both Russian and international notation:

(A chess diagram is a graphical representation of a chess position, showing the chessboard with the pieces and pawns arranged on it. Due to their visual clarity, diagrams are widely used in teaching chess, solving chess problems and studies, and analyzing played games.)

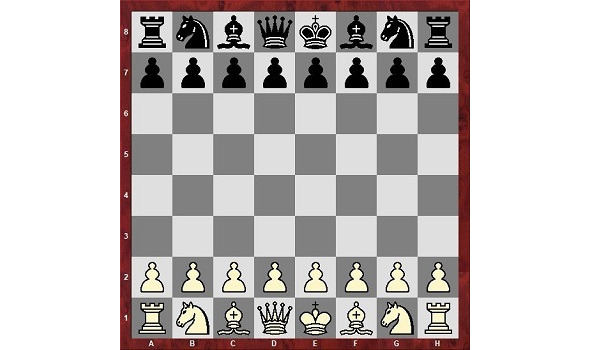

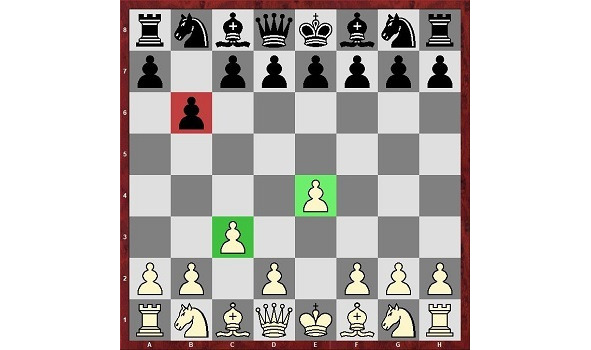

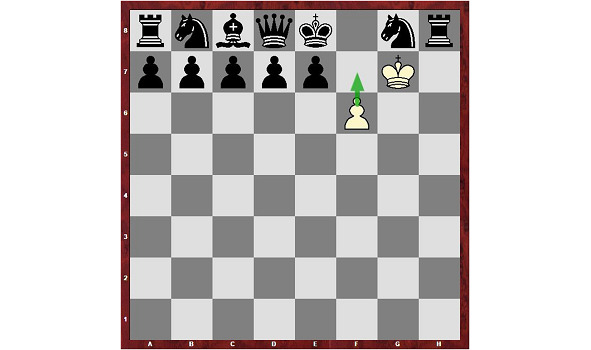

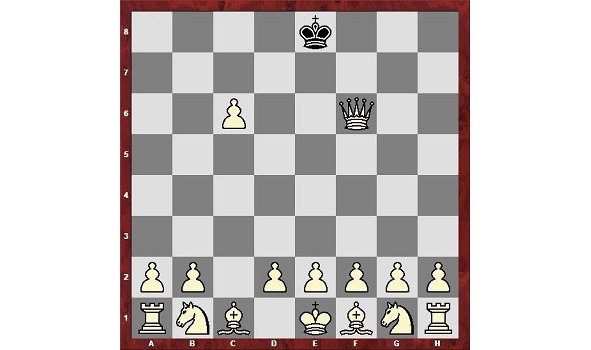

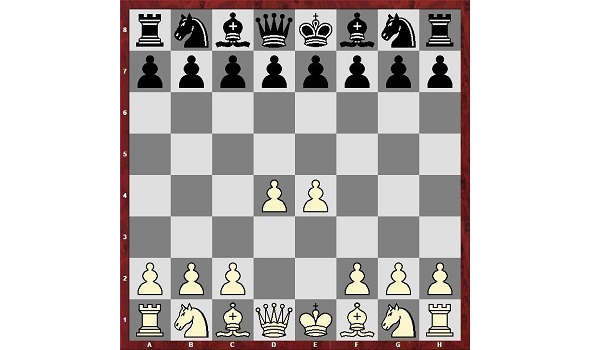

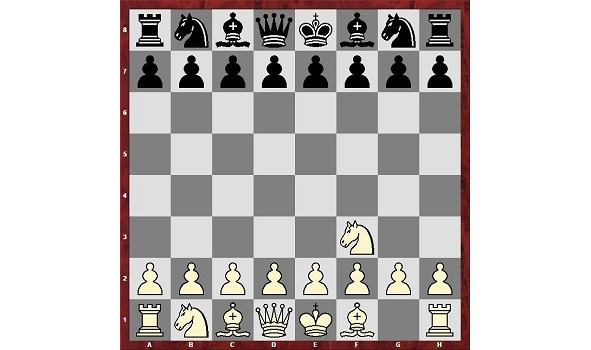

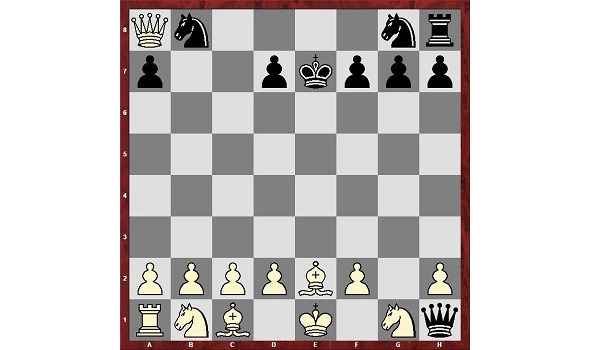

At the beginning of the game, each player has 16 pieces at his disposal: a king, a queen, two rooks, two bishops, two knights, and eight pawns. There are a total of 32 pieces on the board. See the diagram: (Arrangement of shapes)

Attention! The correct arrangement of the board is when the player’s left corner square is black (a1 or h8), which should be remembered! (There are boards without numbering).

First, place the pawns: white pawns in a row along the second horizontal line, and black pawns in a row along the seventh horizontal line.

Then, place the white rooks on the a1 and h1 squares, and the black rooks on the a8 and h8 squares.

Next to the rooks, place the white knights on the b1,g1 squares, and the black knights on the b8,g8 squares.

Next to the knights, place the bishops on the c1,f1 and c8,f8 squares, respectively.

We are left with the queen, the king, and two empty squares on the 1st and 8th rows. To avoid confusion, remember the following rule: “The queen likes its own color”, i.e. the white queen is placed on the white square (d1), and the black queen is placed on the black square (d8). The kings are placed on the remaining squares (e1, e8).

The pieces should be placed symmetrically.

If you have done everything correctly, you will get the following position:

A move in chess. Capturing a piece or a pawn. The general concept of a move: with the exception of castling, a move is the transfer of a piece from one square to another, either an empty square or a square occupied by an opponent’s piece. Moves in chess are made by the opponents in turn. The “touched-move” rule states: If you have already touched a piece to make a move, it must be made with that particular piece. And no other piece. If you want to correct a piece or several pieces on the board, you must warn your opponent with the word “Correcting!” or “J’adoube” if you are playing with a foreigner. J’adoube (in French transcription, “j’adoube”) is the French word for “correcting.” The fashion for using the word J’adoube began in Europe about 100 years ago. In Russia, the use of the term J’adoube is more of an exotic concept. In our country, it is more acceptable to say “I correct” or “Jadub.” Although in our country, they almost always say “I correct.” However, if you are playing abroad or with a foreign chess player, it is preferable to say “Jadub.”

So, if you’ve taken a piece, you must move only that piece and no other.

No piece, except for the rook during castling and the knight, can cross a square occupied by another piece (jump over other pieces).

If a piece moves onto a square occupied by an opponent’s piece, the opponent’s piece must be removed from the board by the player who made the move. This move is called capturing. The only piece that cannot be captured and removed from the board is the king.

Each piece has its own moves and capture of the opponent’s piece (pawn). Let’s explore them all.

Attention!!! After capturing (when we “eat” an opponent’s piece or pawn), the “eaten” piece (or pawn) is removed from the chessboard, and our piece (or pawn) that we attacked is placed in its place.

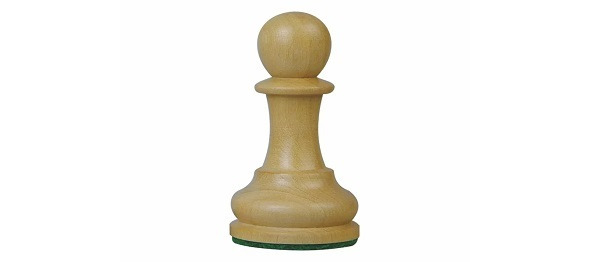

The pawn

The pawn is the only piece whose move and attack rules differ. The rest of the figures match. The nominal value is 1 point.

Pawns only move forward. Attention!!! Pawns do not move back or sideways, unlike the rest of the pieces.

This is the only piece that cannot walk and strike backwards or horizontally. When a pawn is in the starting position (2nd rank for White, 7th rank for Black), it can move one or two squares forward as the player wishes.

After its first move, the pawn moves only one square forward in one move.

The pawn can beat the opponent’s pieces one square ahead diagonally to the right and left.

Thus, a pawn moves forward and strikes diagonally one square. This is the only piece in chess that moves according to one rule and strikes according to another. The other pieces have the same movement and striking patterns.

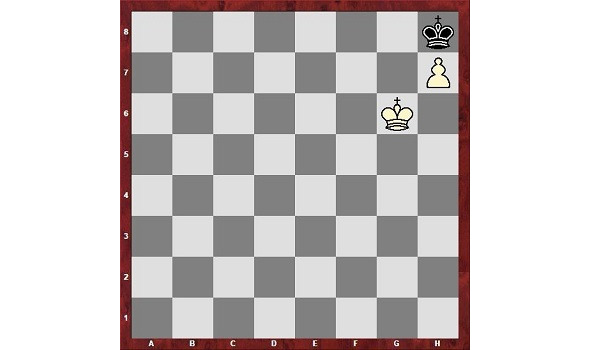

Another important rule is the promotion rule. If a pawn reaches the last rank (the 8th rank for white pawns and the 1st rank for black pawns), it can be promoted to any other piece (except for the king).

Most often, the strongest piece is placed, the queen (but there are exceptions, when it is more profitable to place another piece). Thus, theoretically, it is possible to carry out 8 pawns and place 8 queens (queens are taken from other sets of pieces).

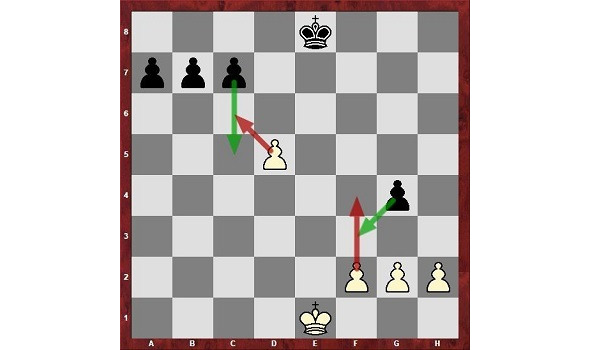

One of the most difficult rules related to pawns is called “capture on the passage.” This is a move in which a pawn can hit an opponent’s pawn if it jumped over a broken field. If a pawn “jumps” over a square that is “pushed through” by an opponent’s pawn, the opponent’s pawn can capture the pawn.

Capturing on the pass is performed on the same move.

Your pawns are your infantry or soldiers. Since infantry walks on foot, pawns move slowly and cannot escape from stronger pieces. In a chess game, there are more pawns than other pieces, and they can be sacrificed to open a line for an attack.

However, pawn has one undeniable advantage, it can be promoted to any piece (except the king), which no other piece can boast of.

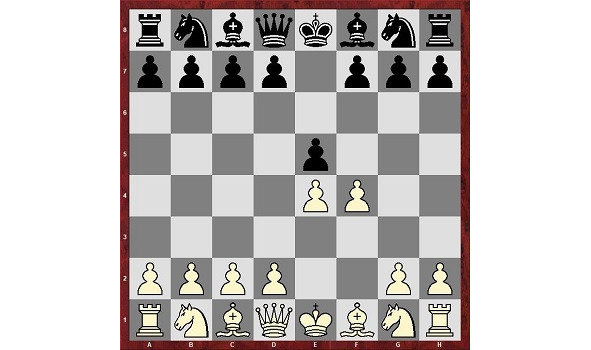

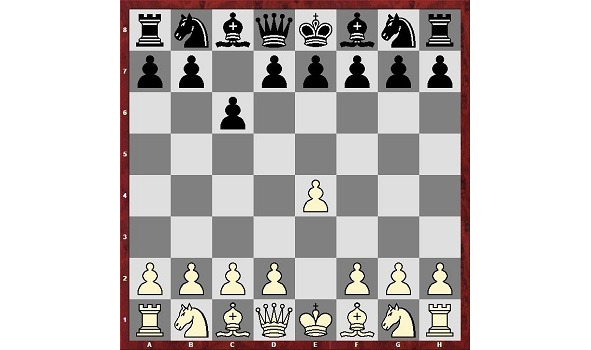

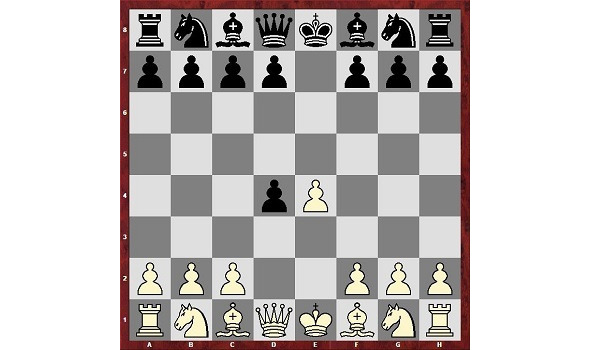

In addition, it is the pawns that determine which opening (beginning of the game) will be played, for example:

1.e4 e5 — open openings

1.e4 c5 — Sicilian Defense

1.c4 c5 — English Opening, etc.

So let’s summarize the uniqueness of the pawn:

It doesn’t go backwards, only forwards.

When the eighth horizontal is reached, the white pawn and when the first is reached, the black pawn miraculously turn into another piece.

He can take the opponent’s pawn through the broken field, that is, “on the pass”

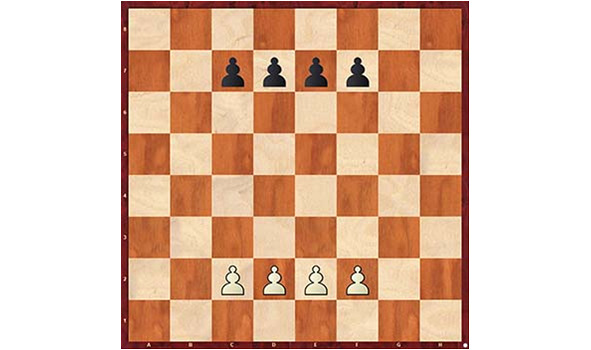

The Pawn game is played according to the rules of chess.

The purpose of the game: whose pawn reaches the end of the board first wins. If the pawns run into each other, then the one whose move is lost (zugzwang- we will study in the future).

The Pawn game is useful because it makes it possible to memorize the movements and captures of pawns, including “taking on the pass”, as the most difficult element in the chess rules. Playing pawns is useful even for those who already know how the pieces move and have little experience playing chess. In the following topics, we will look at examples such as strong, weak pawns (passing pawn, etc.), zugzwang over there, the pawn game will be useful to us again.

It is interesting:

The original version of the game came to Russia not from Europe, but from Central Asia, so the names of the Russian chess pieces have preserved a literal translation from Arabic or Persian. It was only in the 11th century that European chess rules reached Russia. This is why many pieces have received a double name — one from the old Russian chess, the second from the European.

The pawn

The word “pawn” is the same root as “foot”, “infantry”. This name means “foot soldier”.

In other European countries. the languages of the translation of the name of this figure are the same. But in Germany, the name of the pawn « вauer” does not mean soldier, but “peasant”.

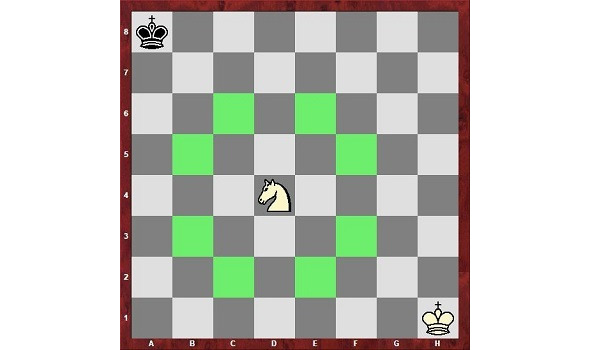

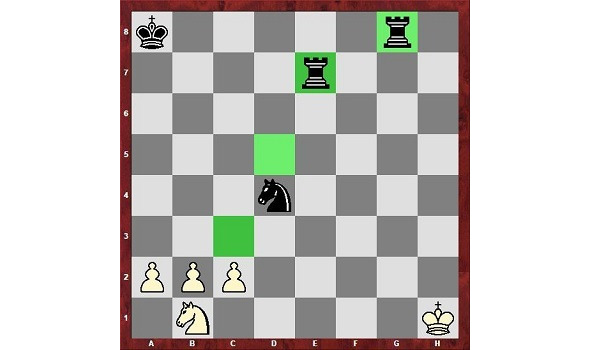

The knight is the most unusual piece on the chessboard. It moves 2 squares forward and 1 sideways (or 1 square forward and 2 sideways) in any direction, forming the letter “G”.

(The knight moves from a black square to a white square and vice versa, but it cannot move from a white square to a white square or from a black square to a black square.) Additionally, the knight can jump over other pieces, so capturing an opponent’s piece occurs only on the square where the knight lands, rather than along its path.

(There is such an expression – “horse move”, that is, a particularly cunning and unexpected step).

For better memorization of how the horse moves, try to solve the famous chess problem “Horse move”.

The goal: to pass all the squares of the chessboard with the horse’s move so that the horse does not visit any square twice. It is best to do this on a piece of paper, numbering the moves. (You can start from the field a1)

It is interesting:

Horse (knight)

In ancient chess, this figure represented a “cavalry” — a rider on a horse. Over time, her image was simplified by removing the rider and leaving only the horse. But in many European languages, a chess knight continues to be called a rider. In France, a chess knight is a cavalier, in England it is a knight.

We just call it “the horse.” In Germany (springer), Poland (skoczek), Croatia (skakač) it translates as “jumper”, “steed”.

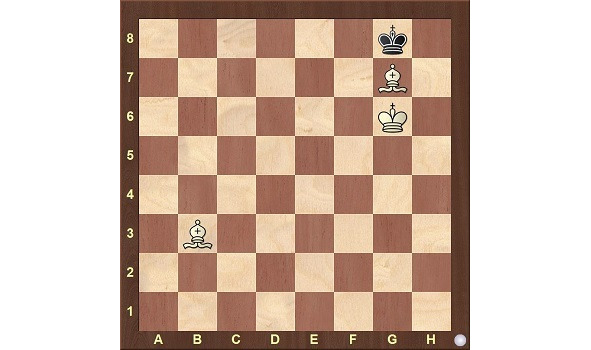

Elephant (bishop)

A bishop is a chess piece of equal strength to three pawns or a knight. Sometimes an elephant is mistakenly called an officer, but we will correctly call it an elephant. In English — speaking countries, the name Bishop is accepted.

The elephant walks diagonally for its entire length if it has no obstacles. At the beginning of the game, each player has two bishops. One moves on white squares, the other on black squares, so they are called white-square and black-square, i.e. elephants are called not by the color of the piece, but by the color of the squares on which it moves. Elephants always stick to the color from which they started the game.

If both of your elephants end up on the same color square, then know that something went wrong and you made an impossible move.

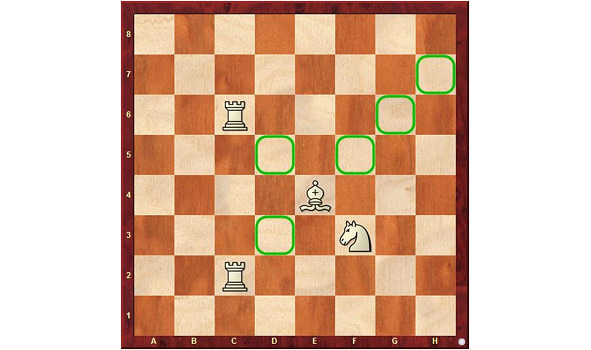

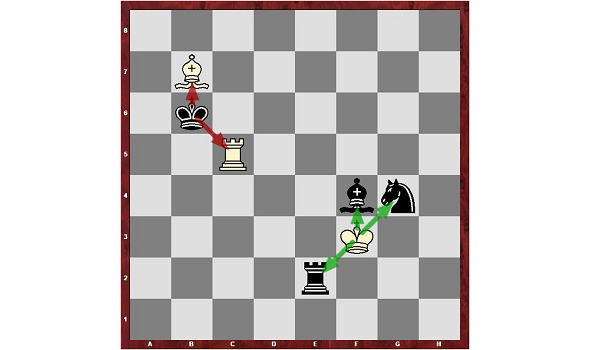

The path of an bishop can be restricted by other pieces on the chessboard. The diagram shows that the bishop has fewer squares it can move to because other white pieces are restricting its mobility.

How the bishop moves

The white bishop can take the black rook — the rook is removed from the board and the bishop is placed in its place.

The bishop’s position after taking the rook.

It is interesting:

Bishop

In ancient chess, it was a piece depicting a war elephant with a rider. Its name was translated literally in Russia, it turned out to be “elephant”.

But in Europe, the name of the unknown animal “elephant” (in Persian “phil”) turned into “fool” (“ful”). In ancient European chess books, you can see that this figure was depicted as a little man in a hat with bells. Until now, in France, the “elephant” is called fou (fu), that is, a buffoon.

Later, in different countries, this person, who was close to the king, received more honorary titles: bishop (bishop) — in England (the upper part of the chess bishop resembles the headdress of bishops — the mitre. If you look at it from an angle, the mitre seems to consist of two parts, and from a distance it looks like there is an incision on it.)

,runner (Läufer) — in Germany, messenger (goniec) — in Poland, shooter (streelec) — in the Czech Republic, hunter (lovec) — in Slovenia and Croatia, officer — in Bulgaria and Greece. And before the revolution, this figure was also commonly referred to as an “officer.” Only later was the ancient Russian name “elephant” officially assigned to it. And the figurine’s appearance remained the same, European. Therefore, a chess bishop does not look like an elephant (a beast with a trunk), but a man in a tall hat (a bishop, an officer).

The Rook

The rook moves in a straight line, up and down vertically or from side to side horizontally. The rook can move to the maximum number of fields if it has no obstacles.

The rook cannot jump over other pieces.

The white rook can move directly up the board and capture the black knight on c8.

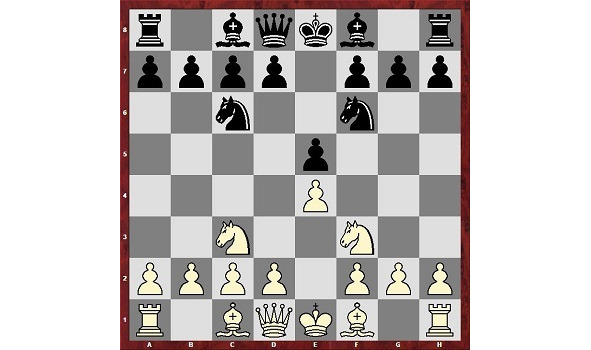

Castling is a special move that involves the use of a rook and a king. In a castling move, the king and the rook are moved along the 1st (white) and 8th (black) rows, and this is considered as a single move. However, there are certain rules that must be followed in order to perform a castling move.

To perform a castling move, you need to move the king two squares in one direction, and then move the rook next to the king on the opposite side. However, there are certain conditions that must be met in order for a castling move to be possible:

For a rook, this must be the first move

For a king, this must be the first move

The path between the king and the rook must be clear (no pieces can block it).

The king cannot be in check or pass an attacked square (also known as a “bitched square”).

There are two types of castling:

1. Short castling — towards the king’s flank.

2. Long castling — towards the queen’s flank.

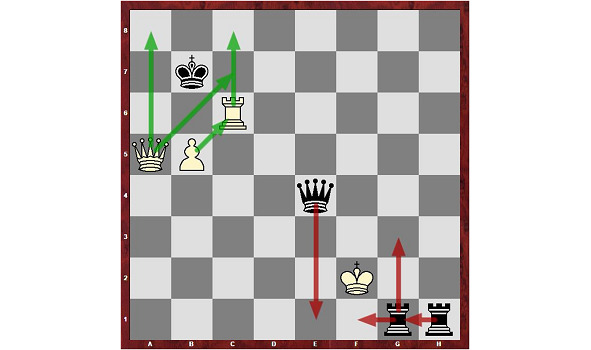

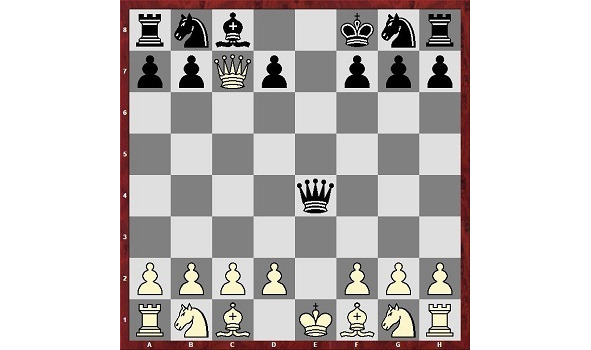

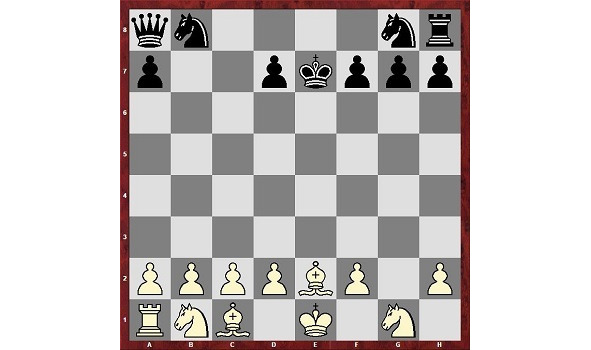

In the diagram, White is doing a short castling, and Black is doing a long castling.

The position of the pieces after castling.

This is interesting:

In the Indian game, a rook is a war chariot (ratha). It was depicted with a team of horses and a charioteer riding them. Apparently, this is where the Persian name for the chariot, rukh, comes from. This is the same Rukh Bird from the tales of “One Thousand and One Nights.” The figure was also depicted as a bird. In Russia, this bird was mistaken for a stylized nose ornament on an ancient Russian vessel, the rook. This is where the figure got its name.

The appearance and other name of this piece, the tour, comes from Europe. In French, it means “tower” (tour). This is also how the French refer to a chess piece. In almost all European languages, the name of this piece means “siege tower” or “fortification.”

In English, it is called a rook (most likely from the Italian rocco, meaning “fortress”) or a castle (castle). In German, the piece is called a tower (Turm). In Polish, it is called a tower (wieża).

Why did the Europeans call the Indian chariot a tower? This was because the Spanish, who were the first to encounter chess, interpreted the Persian word “rukh” as “rocco.” This was their term for siege towers. Therefore, these chess pieces were depicted not as birds or chariots, but as towers.

Until the 15th century, the strongest piece was the rook, which was replaced by the queen. The rook was so important that the player who attacked it had to warn the opponent by saying “Check the rook.”

In order to better remember how the rook moves and hits, I suggest solving the problem.

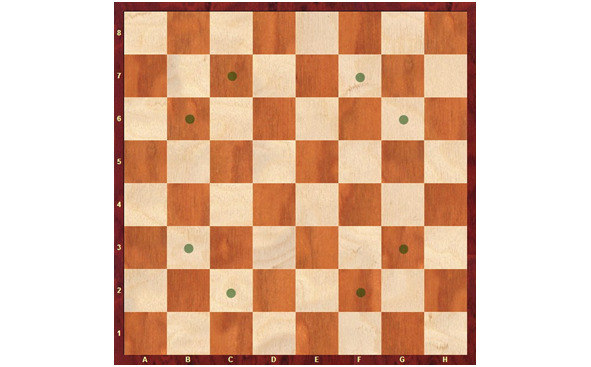

It’s called the “8 Rook Problem.” 8 rooks should be placed on the chessboard (pawns can be used instead) so that none of them beats the other.

There are many ways to do this. Will you find any of them?

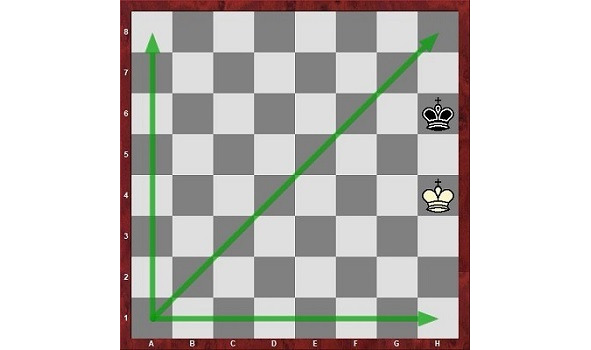

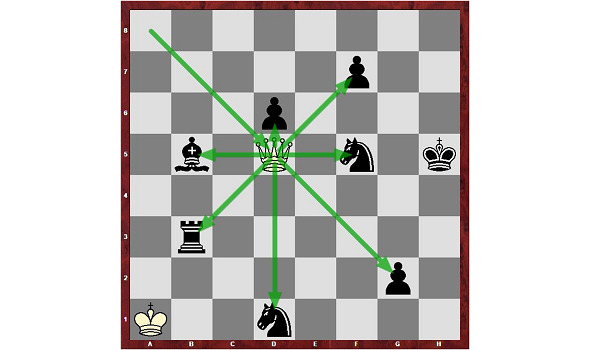

The Queen

The queen is the strongest piece in chess and it stands next to the king. The queen is the strongest piece in chess, but it is not the most important. The most important piece is the king!

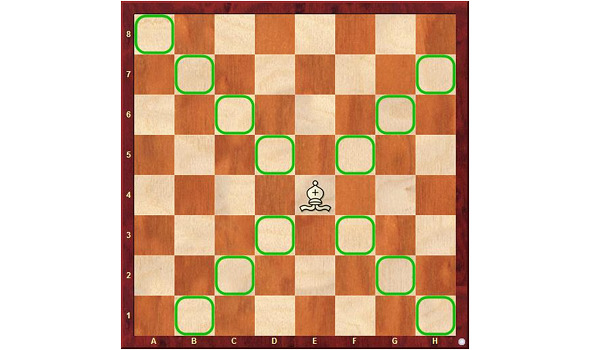

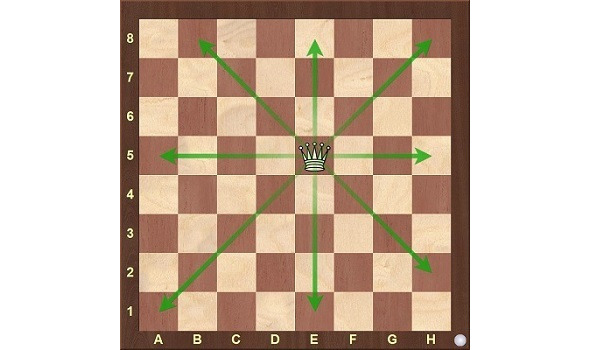

The queen can move any number of squares horizontally, vertically, or diagonally (forward, backward, left, right, or diagonally). However, it cannot jump over any other pieces.

The queen moves in the same way as the rook and the bishop combined. He can move in a straight line like a Rook and diagonally like a Bishop.

A queen beats (“eats”) an opponent’s piece or pawn by moving and taking the place of the defeated piece or pawn.

Is it possible to have two queens in chess?

Yes, it is possible to have two or more queens, with a maximum of 9 queens (theoretically, one queen at the beginning of the game and 8 pawns that can be converted into queens, resulting in a total of 1+8=9 queens).

The queens are taken from a different set of chess pieces.

At the beginning of the game, players only have one queen. A second queen can be added once one of the pawns reaches the other side of the board.

In order to better remember how the queen moves and attacks, I suggest solving a problem.

The problem is called “The Problem of 8 Queens.” On a chessboard, you must arrange 8 queens (or use pawns instead) in such a way that none of them can attack another.

There are many ways to do this. Can you find any of them?

This is interesting:

Queen

The word “queen” came to the Russian language from Persian. There are several suggestions about what it means. Perhaps “queen” is farzana (wise man, advisor), perhaps ferz — “commander” or “vizier” (first minister).

In Europe in the 15th century, “vizier” turned into “queen”. This very weak piece now received new opportunities — the former queen could no longer walk one square diagonally, but along all lines and diagonals for any distance. Many chess historians associate this with the role of the powerful Queen Isabella of Castile in the life of Europe.

(chess appeared in Spain in the 8th century, and until the 15th century, the queen was considered a male figure. In Persian, “al-ferza” means an assistant, adviser.

Columbus asked Isabella and Ferdinand for funding for his voyage.

Torquemada.

The name of this man evokes terrible images in our minds: the burning of people in public squares, the brutal torture in the dungeons of the Inquisition, and the triumph of obscurantism and fanaticism. However, his contemporaries called him the “hammer of heretics,” the “light of Spain,” and the “savior of his country.” So who was this man, the Grand Inquisitor Thomas de Torquemada?

Torquemada was born in 1420. His father was an unremarkable man, but his uncle, Cardinal Juan de Torquemada, was a famous man: he was one of those who sent the famous Jan Huss to the stake (in 1415). But all this was negated by the terrible secret kept by the Torquemada family. The fact is that the grandmother of the future Grand Inquisitor was… Jewish.

What did it mean to be a Jew in the Middle Ages, and in Spain in particular? Their situation was terrible. The only way for Jews to avoid humiliating persecution and even death was to convert to the Catholic faith (such baptized Jews were known as Marranos in Spain).

Thomas learned the secret of his origins as a child. Since then, the boy’s desire had been to rid himself of the “shameful mark” and erase it. How could he do this? Only by fervently serving the cause of the Catholic faith! At the age of 14, Thomas joined the Dominican Order. The Dominican rules were strict, but Thomas was even stricter with himself! He was a complete ascetic: he didn’t eat meat, walked barefoot in any weather, whipped himself with a whip, slept only on a bare wooden bench, wore a rough hair shirt under his clothes that chafed his skin until it bled, and so on.

This is how the Dowager Queen Isabella of Portugal saw him when she visited the Santa Cruz Monastery, where Torquemada was the abbot. The queen was impressed by the religious ascetic’s presence. She could not have found a better tutor for her 7-year-old daughter. At the age of 39, Torquemada became the confessor and tutor of the young Princess Isabella of Castile. Princess Isabella was known for her exceptional education and her devout Catholic faith. Torquemada’s influence on Isabella was enormous. It was he who insisted on her marriage to Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of Aragon. And when in 1474 Isabella became Queen of Castile, and Ferdinand became King of Aragon in 1479, effectively forming a single Spanish state. But it is not enough to “create” a single state on paper — it is necessary to unite it in fact. To this end, in 1483, Isabella appointed Torquemada as Grand Inquisitor of Castile and Aragon.

Columbus requested financing for his voyage from Isabella and Ferdinand.

The classic of American poetry, Henry Longfellow, described Spain at the end of the XV century in his poem “Torquemada” in 1863.:

In Spain, numb with fear,

Ferdinand and Isabella reigned supreme.,

But he ruled with an iron hand

The Grand Inquisitor over the country…

He was as cruel as the lord of hell.

The Grand Inquisitor Torquemada.

The queen moved one square at a time, like the king (in the sense that the advisor could not be stronger than the King, which makes sense). However, with the rise of Isabella of Castile to power, the Spanish began to treat her with respect, and perhaps even fear, and as a result, they changed the gender of the piece and its power as a gift to her (more like a flattery). This was an extremely unusual event for the Spanish, as gender is a crucial issue for them, and the Spanish language does not even have a neuter gender. And a mistake in the indication of the gender is considered rude, even if you are just learning the language. So, the very fact that the queen became a female figure speaks of how great the authority of the queen was.

In almost all languages, the queen became known as the queen or the queen. In France and Germany — Dame, In Italy — Donna, in England — Queen, in Bulgaria — Tsarina, In Macedonia — Kralica. It is curious that only in Poland there was a proper name for the queen — hetman.

From Europe, our colloquial name for the queen came to us: “queen”. When recording a chess game in our country, the queen is written with the letter “F” — Queen, while in the international chess community it is written with the letter “Q” — Queen.

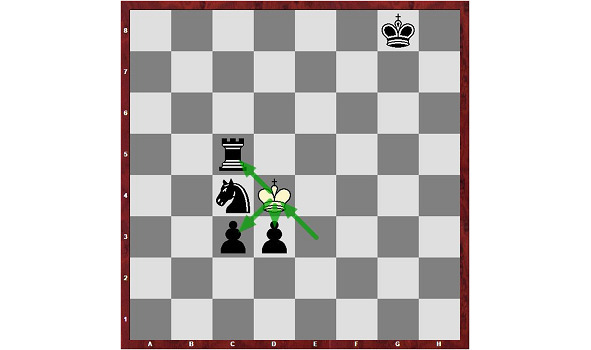

King

The King is the main chess piece, but it is not the strongest. The goal of a chess game is to checkmate the opponent’s king (i.e., put it in a position where it has no defense). The king cannot be removed from the board, as it remains on the chessboard until the end of the game.

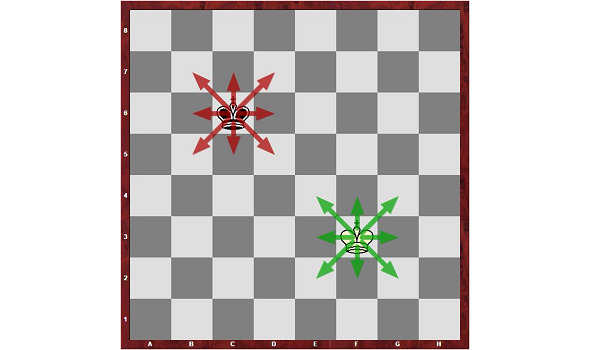

The King can move one square in any direction, horizontally, vertically, or diagonally, forward, backward, or sideways.

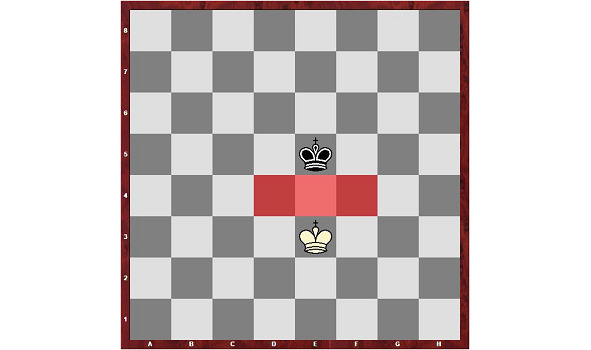

Unlike other pieces, the King cannot move to a square that is under attack from an opponent’s piece (under check) or another King.

Attention! The minimum distance between the kings of both sides must always be one square, which neither of them is allowed to occupy.

The Кing cannot jump over other pieces (like the knight, except for castling) and cannot be sacrificed (the king is not “eaten”). We have already discussed the rules of castling when studying the rook.

The Кing can attack any piece of the opponent that is adjacent to it, even the queen, if the occupied field is not protected by another piece or the king (since such a move is considered impossible due to the threat of checkmate).

This is interesting:

King — from the Persian name “al-shah” — king.

The name of the game itself comes from the Persian words “shah” and “mat”, literally — “the king (or shah) died”.

The chess king in all languages denotes the supreme ruler.

In England — king, in Gerмania — König, in France — roi, in Bulgaria — Tsar.

The value of the pieces is nominal (in a real game, the power of the pieces depends on many things, which we will study. (Sometimes a pawn is stronger than an entire army).

Pawn – 1 point, Knight – 3 points, Bishop – 3 points, Rook – approximately 5 points, approximately Queen – 9 points, King is priceless.

Since the pawn is 1 point, it is customary among chess players to evaluate the figures by the number of pawns.

The value of the figures is necessary to know in order to understand which figure can be exchanged for the opponent’s figure, whether it is beneficial or not. For example, a Knight can be exchanged for an Elephant, which is an equivalent exchange (assuming the positions are equal), and it is advantageous to exchange a Knight or an Elephant for a Rook, resulting in a gain of approximately two pawns (known as a “quality” gain in chess terminology). A Queen is approximately equivalent to two Rooks, and so on.

Knights and Elephants are referred to as “light pieces,” while Rooks and Queens are considered “heavy pieces.”

The rules of the FIDE game, the move

So, the move is considered to be made:

when moving a piece to a vacant square, when the player’s hand releases the piece;

when capturing, when the captured piece is removed from the board and when the player, placing their piece in a new location, releases it;

when castling, when the player’s hand releases the rook that has become on the square that the king has crossed;

when a pawn is promoted, when the pawn is removed from the board and the player releases their hand from the new piece placed on the promotion square;

Touching a piece.

By warning the opponent in advance, (saying “I’m correcting”) the player can correct the position of one or more pieces on their boards.

Otherwise, if the player touches:

one or more pieces of the same color, they must move or capture the first piece they touched that can be moved or captured

one of their own pieces and one of the opponent’s pieces, they must capture the opponent’s piece with their own piece; or, if this is not possible, they must move their own piece; or, if this is not possible, they must capture the opponent’s piece with any

1.4 Attack on a piece, checkmate, stalemate, draw.

Attack is the creation of a threat to capture an enemy piece.

Attack on an enemy piece occurs in the direction of your piece’s movement, except for pawns and knights.

For example:

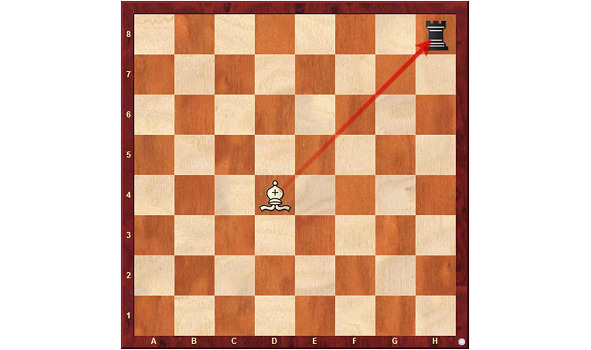

A bishop both moves and attacks a piece or a pawn of the opponent.

A rook can both move and attack an opponent’s piece or pawn.

A queen can both move and attack an opponent’s piece or pawn.

A king can both move and attack an opponent’s piece if it is not protected by another opponent’s piece or pawn.

Please note! The king did not attack the knight, as it is protected by the rook.

The knight, unlike other pieces, does not attack in the same way as it moves. It seems to jump over the pieces in its path and attacks the opponent’s piece that is standing on the square where it lands after its jump.

A pawn, unlike other pieces, does not attack in the same way as it moves.

(it moves straight and attacks diagonally (at an angle)).

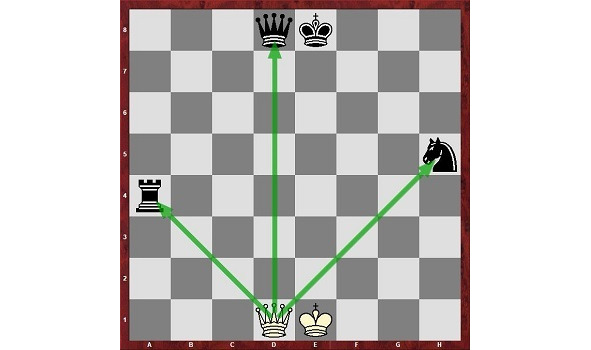

Garde (French gardez “take care”) — an attack on

the farm (obsolete; the declaration “garde” is not necessary).

This is the fall of the king.

Check the Elephant.

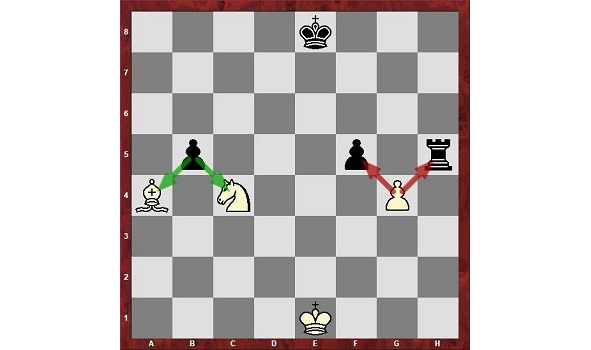

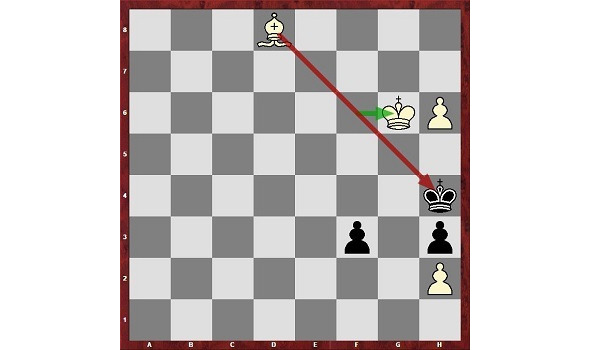

A double checkmate — is when the king is attacked by two pieces. A double checkmate. The knight was on d2 and blocked the rook, then moved to e4, checkmated the black king, and opened the white rook, which in turn also checkmated the enemy king.

If the white bishop moves to b5, then the black king will be in check from the bishop and the rook.

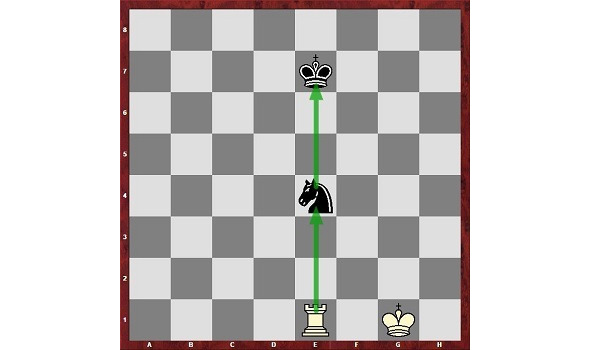

Perpetual check is when the king has no way to escape or defend against checks, and the attacking side (the one giving the checks) has no way to checkmate, and cannot strengthen their position (for example, if they stop giving checks, they will be checkmated themselves.) Perpetual check is a draw (usually by agreement of the parties or by the judge’s award; three-fold repetition of the position or the 50-move rule).

An example of perpetual check. White is in checkmate, with no defense, so White is forced to give perpetual check on the green-colored squares. Black’s king cannot escape checkmate or defend itself. It is a draw.

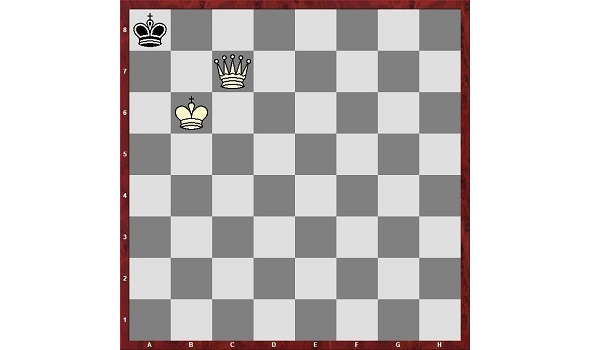

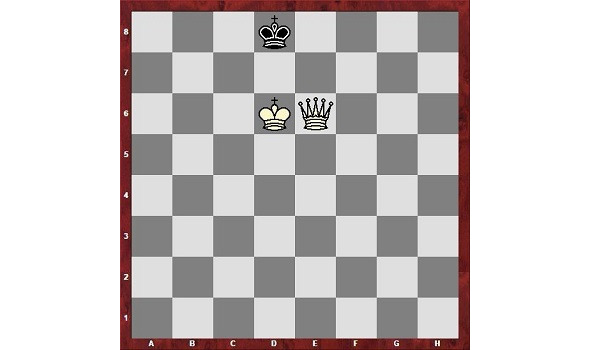

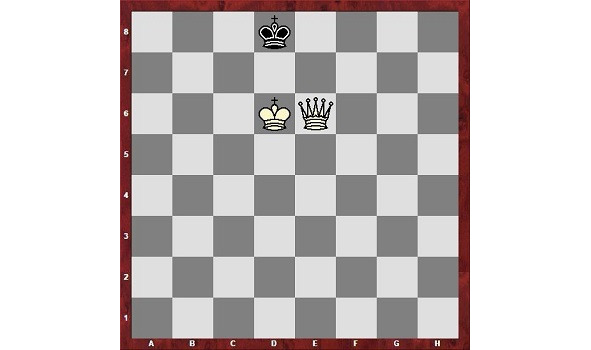

Mate is an attack on the king (check), from which there is no defense.

THE GOAL OF THE GAME OF CHESS IS TO GIVE A MAT TO THE ENEMY KING.

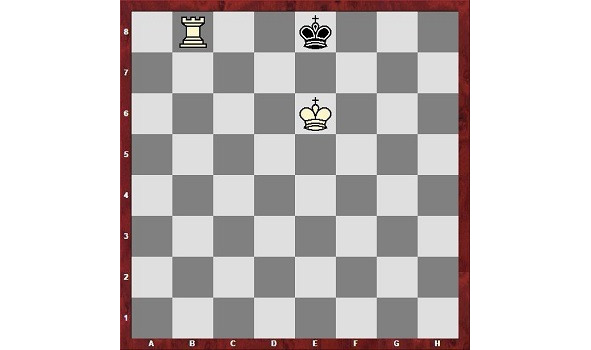

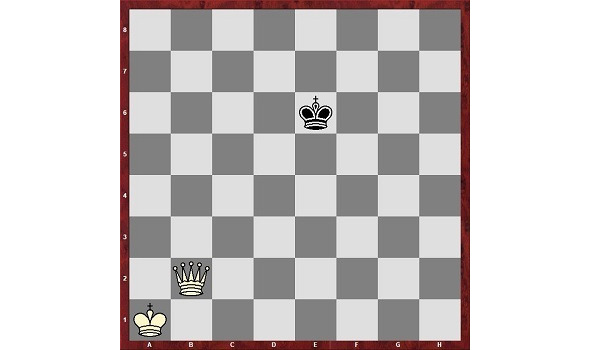

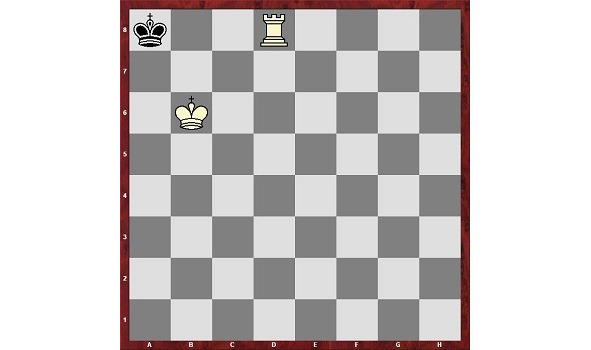

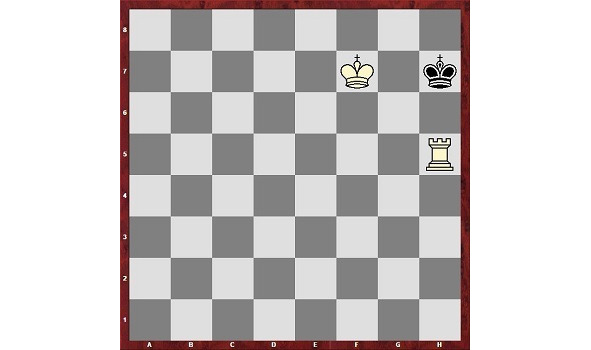

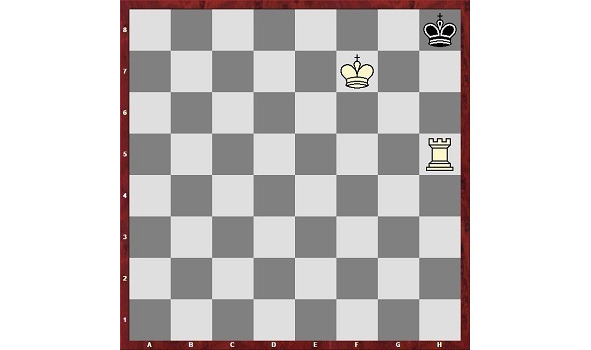

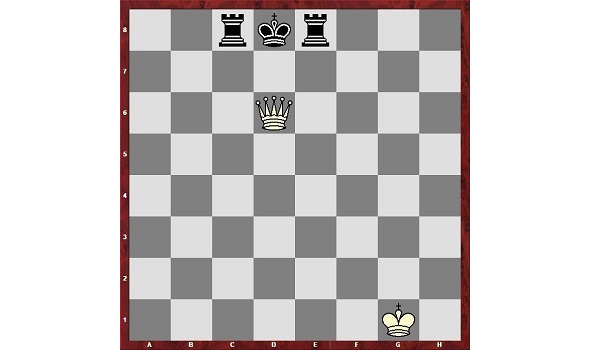

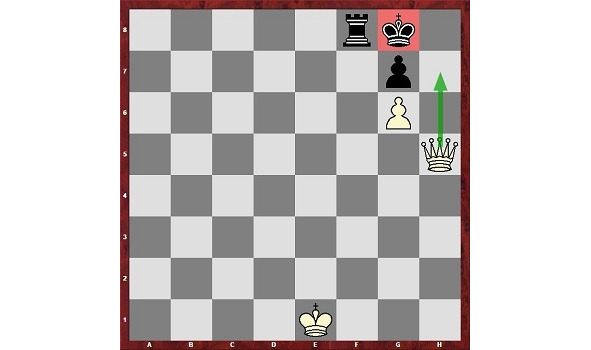

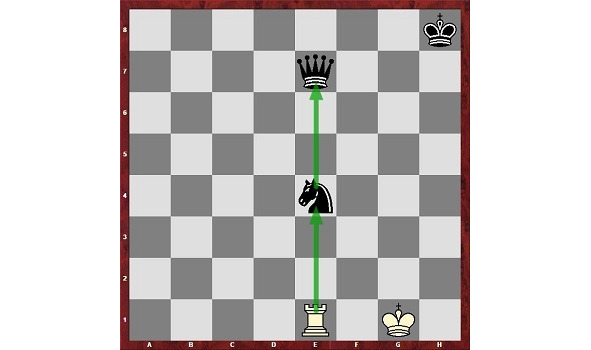

The so-called Linear Mate (the mate is given by “heavy pieces”, rooks or a rook and a queen along the lines — horizontal or vertical.

A rook checkmate is placed when the King is on the edge of the board and the King of the attacking side is directly opposite it.

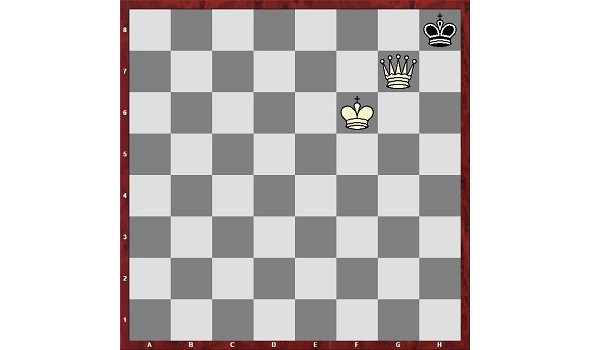

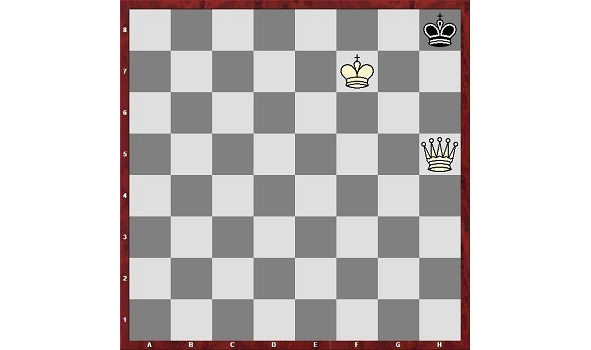

Checkmate with a Queen and a King. (It is customary to say checkmate with a Queen, of course, meaning checkmate with a Queen and another piece, since it is impossible to checkmate with a single piece. Even a “stolen” checkmate (see below) is checked with the participation of the opponent’s pieces.

A draw in chess.

A draw in chess is the result of a game in which neither player was able to win. For a draw, each player receives half a point.

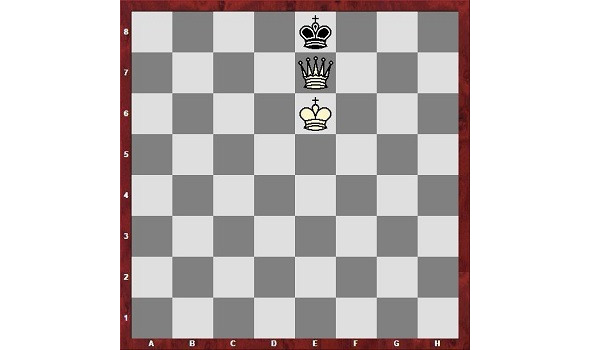

A stalemate is a position in which the player who is supposed to move cannot make a move (there is nowhere to move), but their king is not under attack (in check), and the game automatically ends in a draw.

Even if your opponent has an army and you only have one King, a draw is still possible. Draw.

A stalemate is also possible with many pieces.

A multi-piece stalemate position. The black pieces cannot make any moves, and the King is not under check — Stalemate. Draw.

A draw is recorded in the following cases:

1. By agreement of the players.

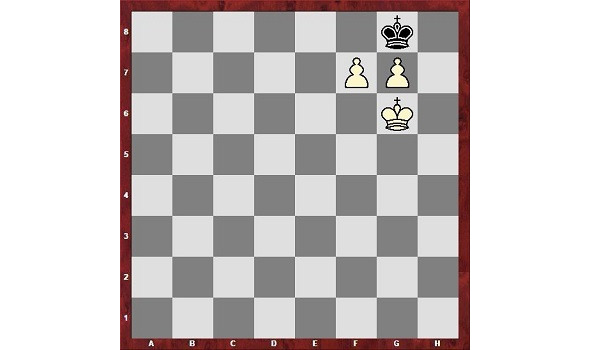

2. There is not enough material (pieces) to win.

For example, only kings remain on the board, a king and a knight against a king, a king and a bishop against a king, a king and two knights against a king

3. By the judge’s award. Repetition of the position three times (not necessarily in succession). If the players have not made a single pawn move in the last 50 moves, nor have they made any captures, then the game is declared a draw.

FIDE rules of the game, partners

Chess is usually played by two players (called chess players) against each other. It is also possible for one group of chess players to play against another or against one player, such games are often referred to as consulting games. In addition, there is a practice of simultaneous game sessions, when several opponents are playing against one strong player, each on a separate board.

In modern official tournaments, the rules of the International Chess Federation FIDE apply, which regulate not only the movement of pieces, but also the rights of the referee, rules of conduct for players and time control. A game played remotely, such as by correspondence, telephone, or the Internet, has special rules. There are many variations of chess that differ from the classic game, such as those with non-standard rules, pieces, board sizes, and so on.

Chapter 2

Chess notation. How to start a chess game. (Child’s checkmate, checkmate in 2 moves, Legal’s checkmate.) Opening (opening classification, gambits), middlegame, endgame. How to play the opening correctly. Which openings should be played and why. (open)

Chess notation

Currently, chess tournaments are played with different time controls. There are classical tournaments (60 minutes or more for each player), rapid tournaments (less than 60 minutes for each player), and blitz tournaments (less than 10 minutes for each player).

In classical tournaments, it is customary to record chess games. This is done using a special notation system. It is necessary to know it in order to be able to watch games (in chess books, magazines, solve chess problems and combinations, etc.), record your games and analyze mistakes, watch games of masters and grandmasters in order to learn.

Chess notation (full and incomplete, Russian and international), recording a chess game.

K — King — K

F — Queen — Q = 9—10 pawns

R — Rook — R = 5 pawns

B — Bishop — B = 3 pawns

N — Knight — N = 3 pawns

p — (pawn or nothing). = 1 pawn

For example, a child’s checkmate in Russian notation is written as follows:

1. e2—e4 e7—e5

2. Bf1—c4 Nb8—c6

3. Qd1—h5?! Ng8—f6??

4. Qh5×f7#

Attention!

Castling, both in Russian and in international notation, is written as follows:

in the long side 0-0-0, in the short side as 0—0.

Reduced notation of moves

The initial field and dash are omitted. The same game in reduced Russian notation looks like this:

1. e4 e5 2. Сc4 Кc6 3. Фh5 Кf6?? 4. Ф:f7#

In the international version of the notation, this checkmate will look like this:

1.e4 e5 2.Bc4 Nc6 3.Qh5 Nf6 4.Qf7# so only the name of the pieces is changed from Russian to Latin.

If the notation does not record the move unambiguously (for example, two identical pieces can move to the same square), one of the coordinates of the original square is added, for example, Rae1 or N3c4.

One of the coordinates of the source field is added, for example, Rae1 or N3c4.

Pawn captures are recorded cd4. Sometimes (most often in the old literature) there is a cd4 or cd recording (if unambiguous).

For a check, a plus sign (+) or two plus signs (++) is a double check. For the mat — there is a grid (#), in the old version (x).

For a draw, there is a "=" sign.

! — good move.!! — a great move.

!? — an interesting move. For example, a clever trap in a lost position.

?! — a questionable move. For example, a sacrifice that requires a complex attack.

? — a mistake — a bad move that should not have been played.

?? — a gross mistake or a clear “yawn”. For example, putting a queen in check or not seeing an opponent’s checkmate.

In this case, the “Yawn” was the move 3...Nf6??, where Black “Yawned” the checkmate 4. Qf7#, although it was possible to defend against the checkmate, for example: 3…g6.

The reasons are different: making hasty decisions related to overestimating their capabilities, playing into a trap, chasing the beauty of the position, chess “blindness” – just does not see, time pressure, does not feel danger, fatigue.

Yawn do usually novice chess players, but happen and with Grandmasters.

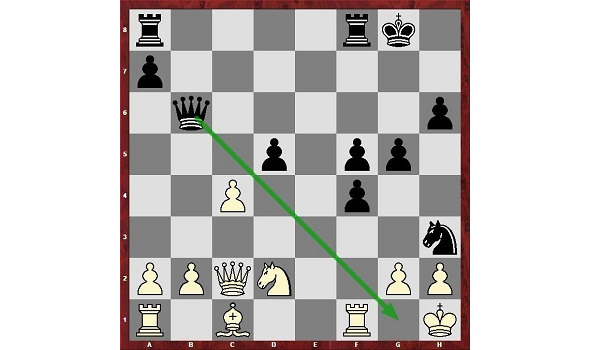

Famous « Yawn” and Examples of yawn grandmasters

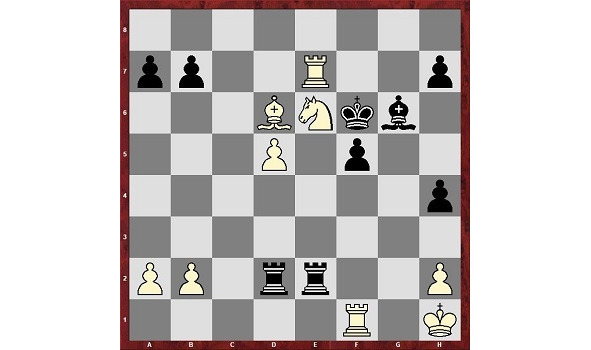

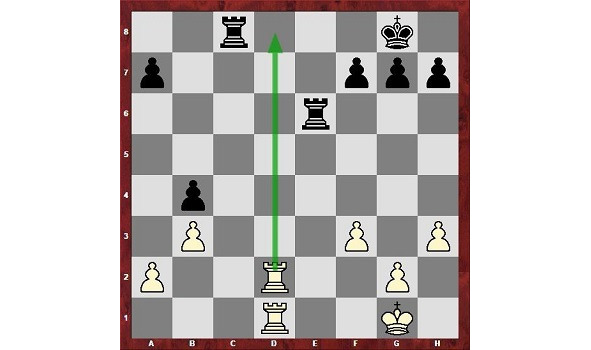

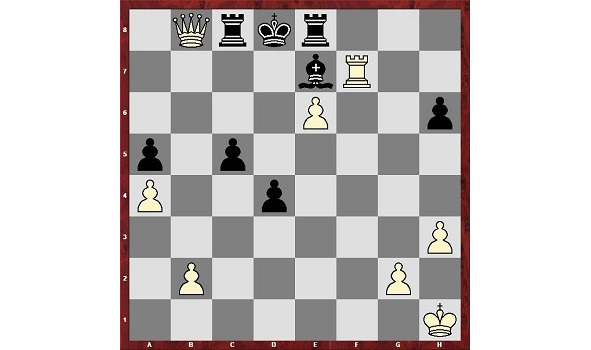

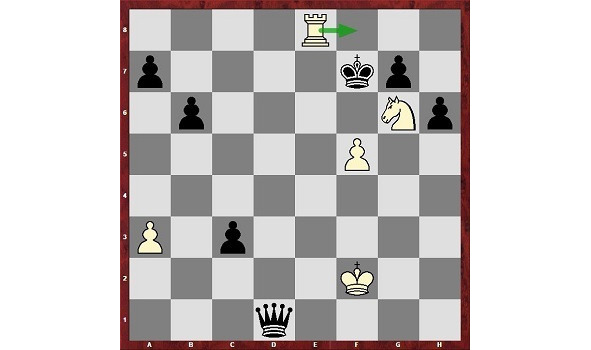

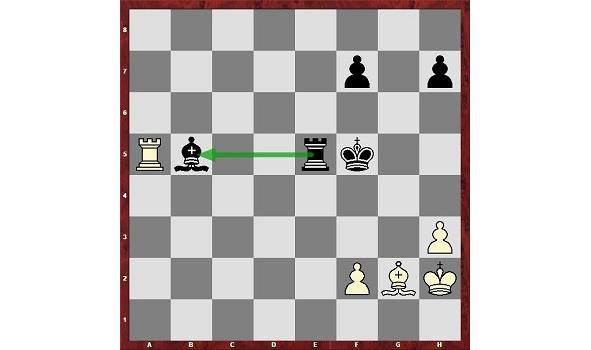

Chigorin — Steinitz, 1892

The 23rd game of the 1892 World Chess Championship match

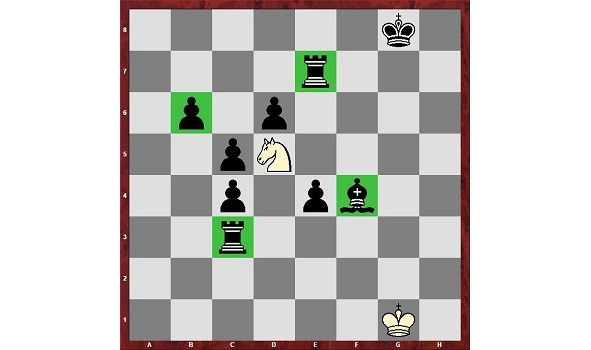

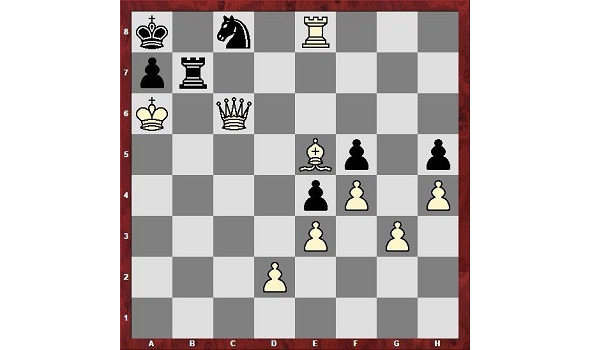

Chigorin — Steinitz, 1892

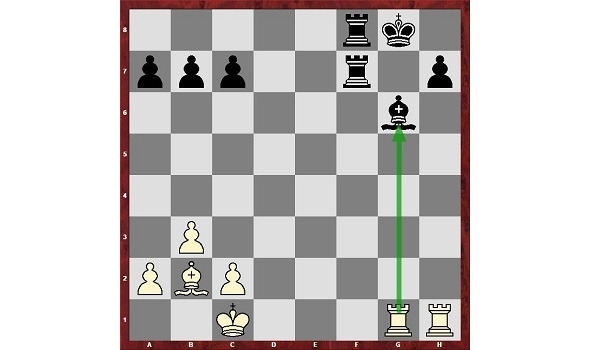

The position is practically won for White. And in this situation White makes a gross oversight: Chigorin attacks the black rook with a bishop, forgetting that it protects the h2-pawn. 23. Bb4??

After a quite predictable response

23. … R:h2+

Chigorin resigned, due to the inevitable checkmate 24. Kg1 Rdg2#. This yawn cost the Russian maestro the entire match. Later, Chigorin wrote that he attributed the yawn to fatigue; by the end of the two-month match, he was completely exhausted.

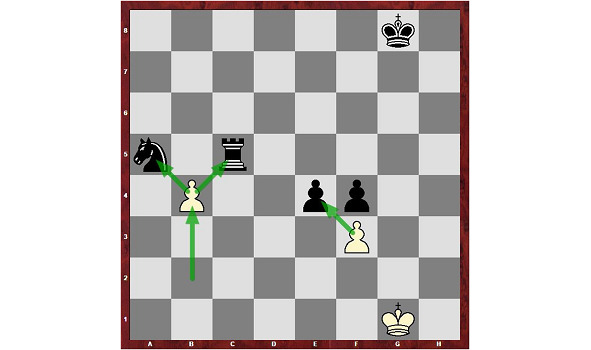

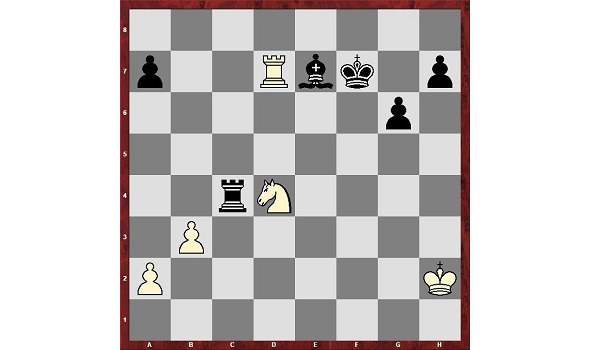

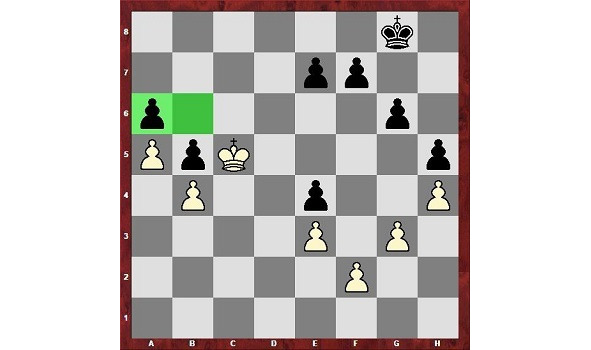

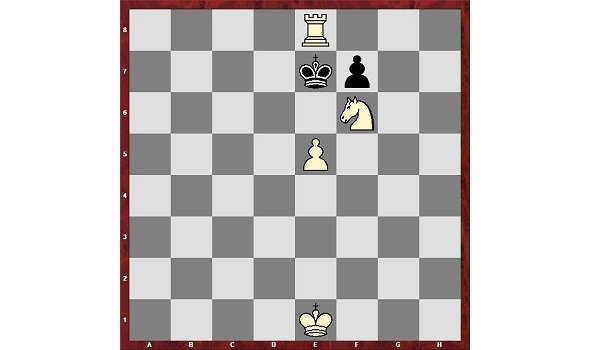

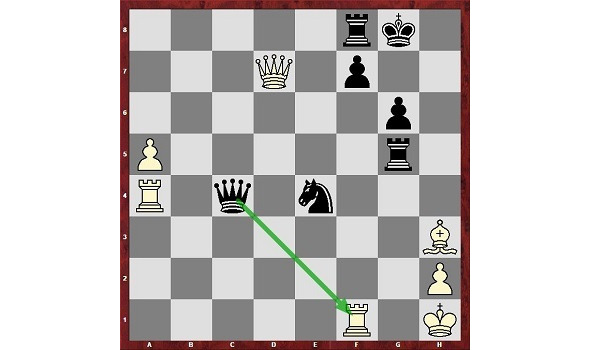

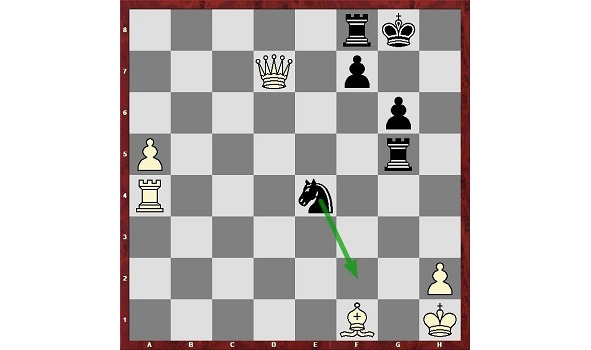

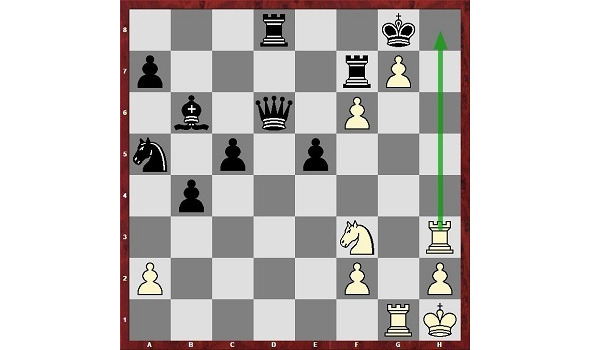

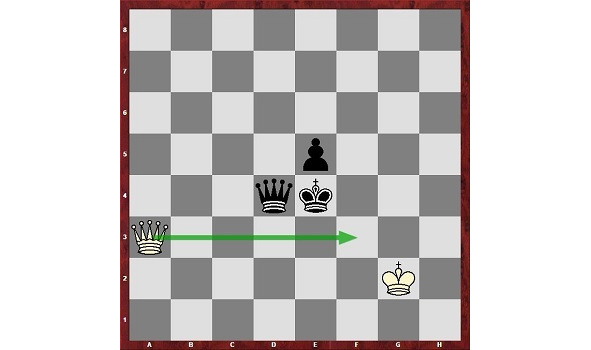

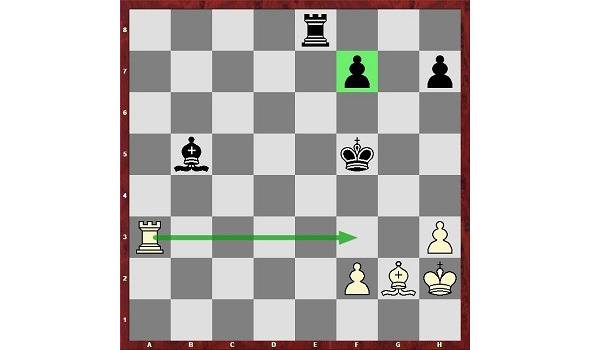

Ebralidze — Ragozin, 1937 USSR Championship

To the position on the diagram, both came in a time-pressure, apparently this is the reason for the mutual “yawn”. Black played: 40…Rc7??. They expected that on 41. R:c7 will follow 41...Bd6+ with the recapture of the rook, but they forgot that the bishop is tied. The most surprising thing was that Ebralidze, like his opponent, believed that this variation was possible, and played 41. Rd5??

Soon, Ebralidze made another serious mistake: 41. …Bf6 42. Nb5 Rc2+43. Kg3 a6 44. Rd7+ Ke8 45. Rc7?? Be5+

and the game ended in favor of Ragozin.

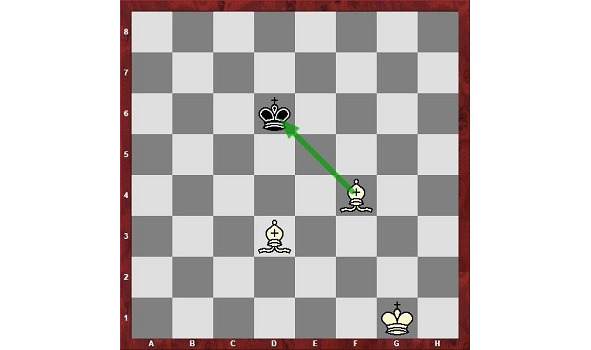

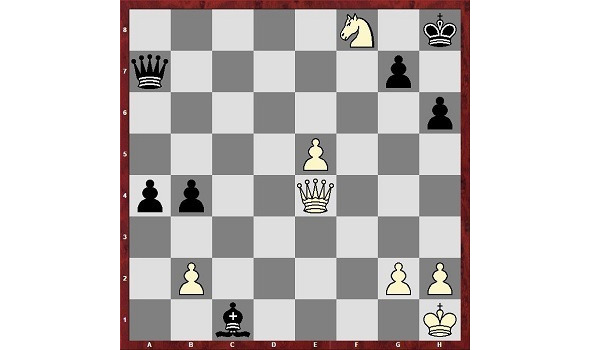

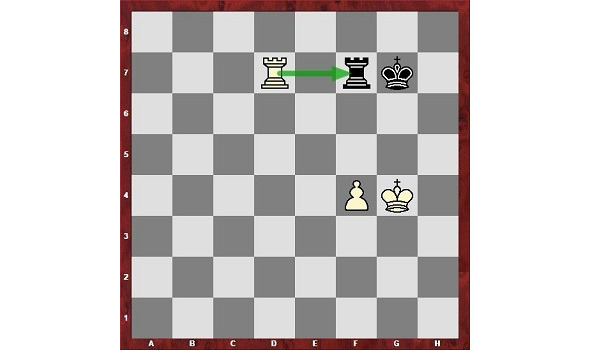

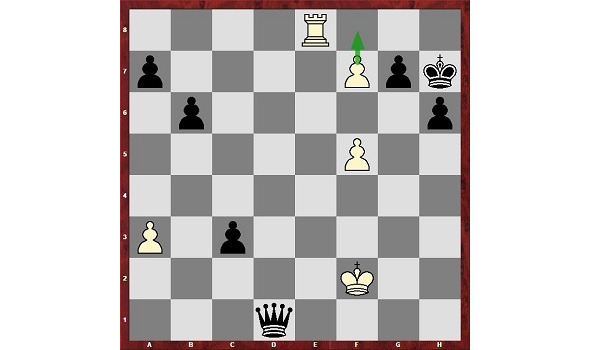

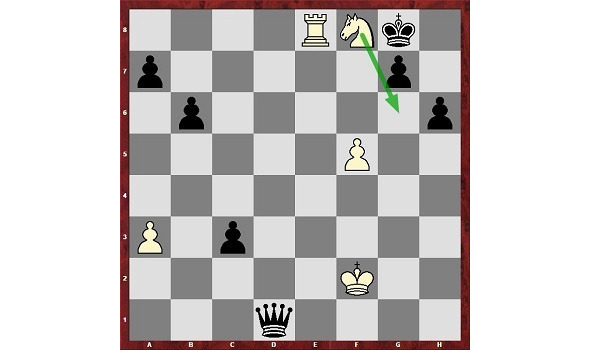

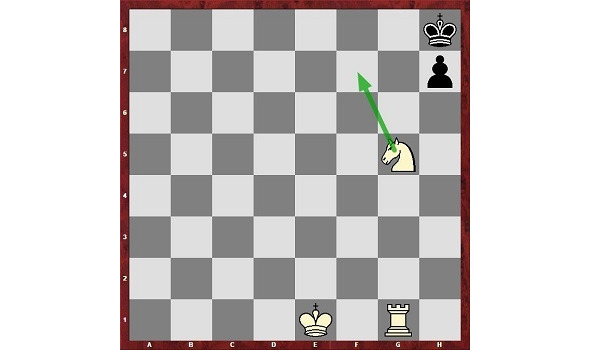

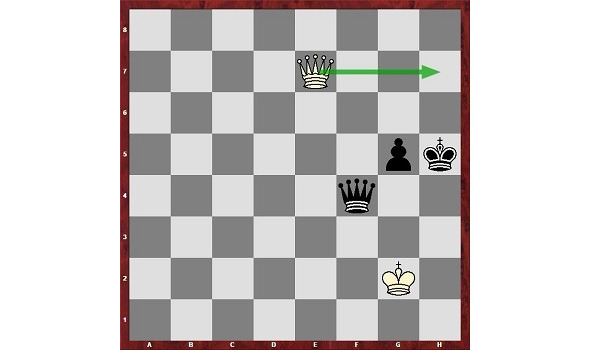

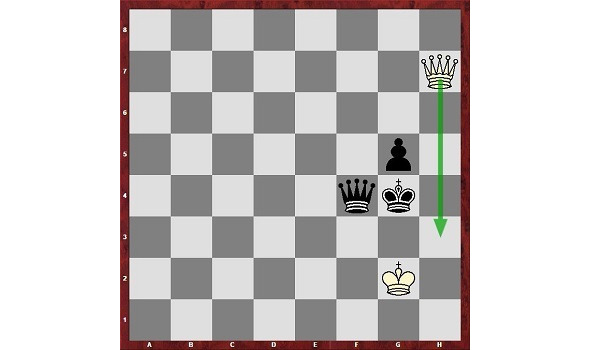

Deep Fritz — Vladimir Kramnik, 2006

match of the chess program Deep Fritz with Vladimir Kramnik. In the second game, Black has this position. Black is better, but White has every chance to draw the game. But here the current world champion makes a gross mistake.

Deep Fritz — Vladimir Kramnik, 2006

34… Qe3?? 35. Qh7#

This incredible miscalculation was called the “yawn of the century” by Zsuzsa Polgár. Kramnik himself admitted at a press conference after the game that he could not explain his yawn.

TIP

When you learn chess notation, be sure to write down your games so that you can analyze them. Review your game again, move by move. Think about where you could have made different moves, what you (or your opponent) didn’t notice during the game, and what mistakes you made. Self-analysis is crucial for improving your skills as a chess player, even if you’re a world champion.

Try not to play against opponents who are much weaker than you (you won’t learn anything from them) or against opponents who are much stronger than you (you’ll lose and won’t even understand why). Choose opponents who are slightly stronger than you, so you can learn from their skills while providing adequate resistance and maintaining your enjoyment of the game.

Beginners should not play with the computer. Chess computer programs are too weak at easy levels and make stupid mistakes that a human would never make, and too strong at difficult levels. Try to play with real people. If you don’t have opponents in real life, find them online. Participate in amateur tournaments.

But once again, try to play with real people. Find 2—3 opponents of your own skill level. Why 2—3 and not just one? Because each player has their own unique style and skill level, which is what makes chess so fascinating. Even if they play the same opening, they will still have different approaches to the game.

Solve combination problems, it is mandatory! Solving combinations develops the so-called combination vision. Since combinations occur in almost all games, it is vital for chess development. They train the vision of tactical combinations and prepare for real play. Having learned to cope with training problems, you will find a solution faster in practice.

Masters and grandmasters do not think about simple chess combinations, they see them from afar and try to bring their opponent to a position where they can execute this combination. Therefore, the knowledge and execution of simple combinations should be automated. It is preferable to solve combinations from practical games rather than from beautiful problems and studies (beautiful problems and studies are more for the aesthetics of chess than for practical play). The more combinations you solve, the faster you will improve your skill.

Make it a rule to solve a certain number of combinations every day (10,20,30), but try to solve them every day. You will know when you are strong enough in combination vision (when you can easily solve combinations in a few moves. HOWEVER, THERE IS NO LIMIT TO PERFECTION. In addition, good combination vision saves a lot of time during a game, especially in blitz or rapid games. COMBINATIONS WITH SOLUTIONS AND EXPLANATIONS are available in separate collections.*

Analyze the games of masters.

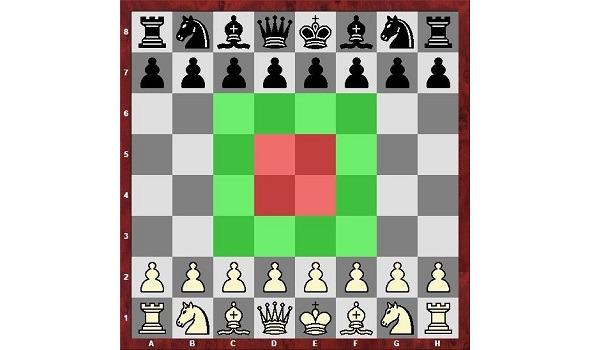

How to start a chess game

Principles of playing in the opening.

REMEMBER THREE WORDS (this is easy and will be remembered for life).

Centre. Development. Castling.

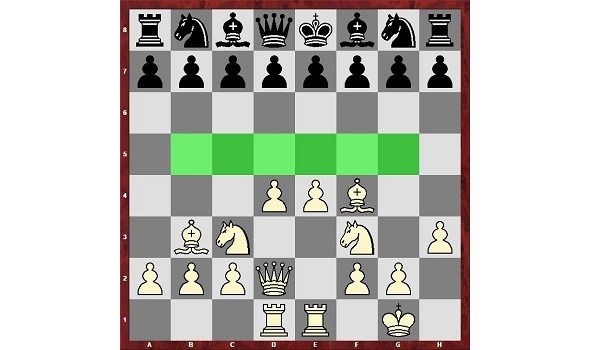

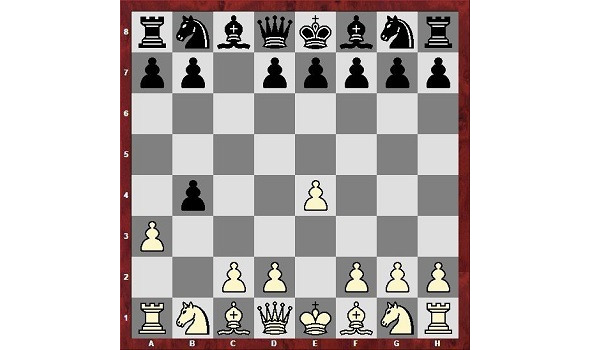

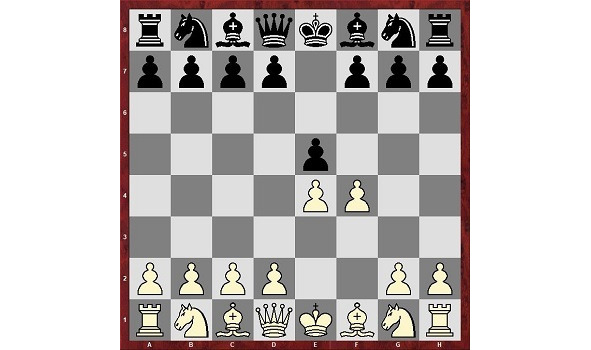

1. Center. Capture the center with pawns.

Capturing the center with pawns.

Why the center? Because whoever controls the center has an advantage, for one simple reason: it is easier to move pieces from the center to any of the flanks.

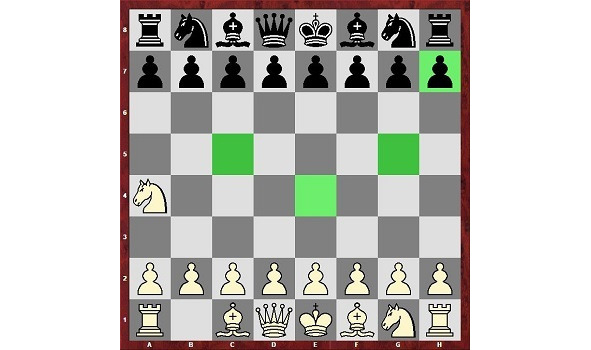

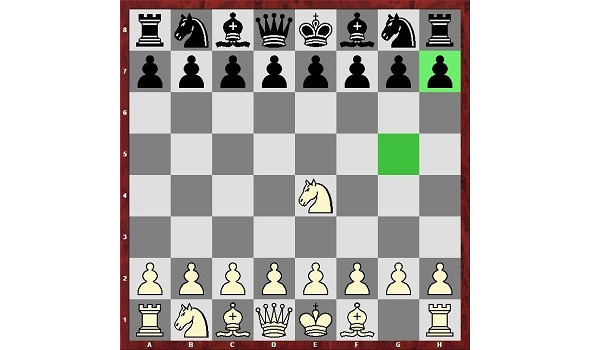

For example, consider how long it takes for a knight to move from one flank to another or from the center to a flank. Let’s say it needs to assist in an attack and reach the h7 square.

He needs 4 moves, but only 2 from the center.

In chess, every move counts. The same goes for other pieces. Although they are long-range, they are still closer to the center, especially since the game often shifts from one flank to the other, and it is faster to move pieces to the flank if they are in the center.

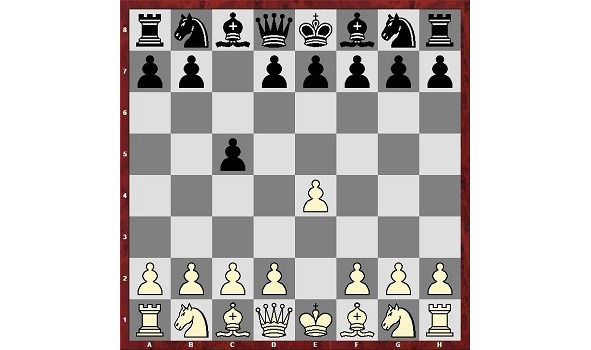

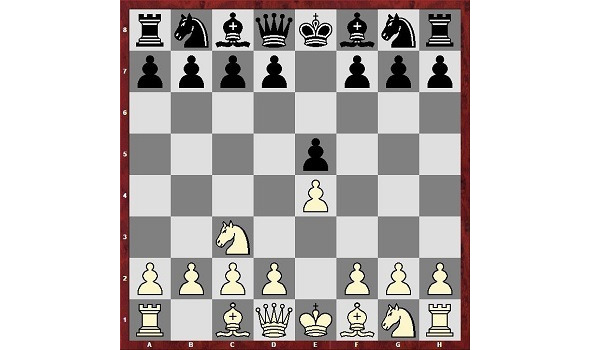

If given the opportunity, capture the center with your pawns. However, there is a nuance in semi-open openings, where Black intentionally gives up the center in order to undermine it later.

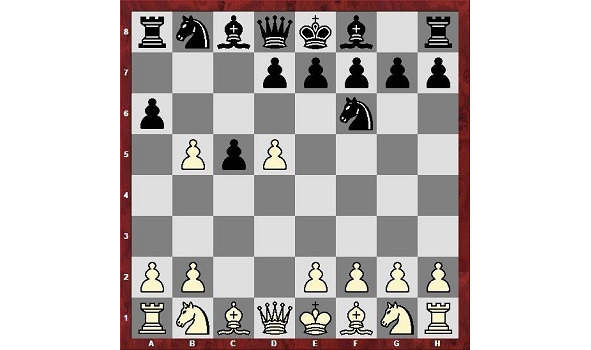

This is especially noticeable in Alekhine’s defense after the moves

1.e4 Nf6 2.e5 Nd5 3.d4 d6 4.c4 Nb6 5.f4

Nimzowitsch’s Opening

1.e4 Nc6 2. d4

in the Pirc-Ufimtsev defense.

1.e4 d6 2.d4 Nf6 3.Nc3 g6 4.f4 Вg7

But more on that later.

By the way, this is how you can immediately determine whether the player is a beginner or a master. However, beginners often give up the center due to a lack of knowledge about opening play. Therefore, feel free to occupy the center.

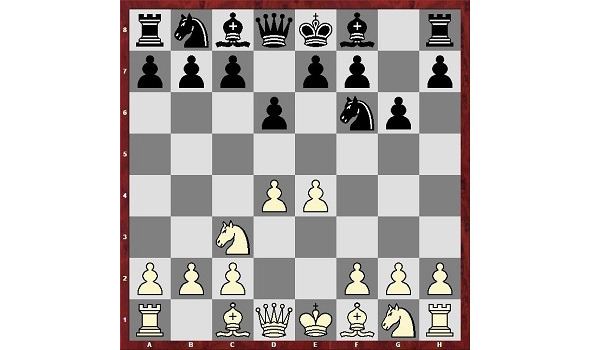

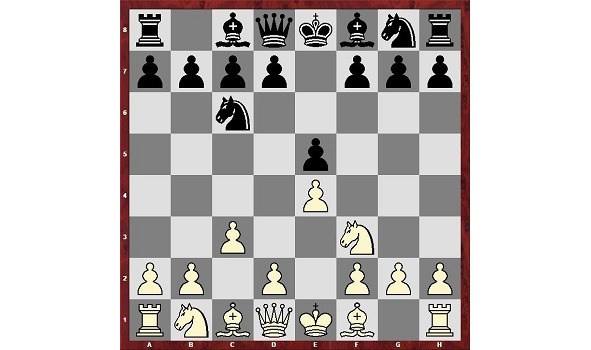

2. Development. Rapid development of pieces (first of all light knight, bishop).

We need to actively use our pieces from the very beginning — to exert constant pressure on our opponent’s position and ultimately — to win. That’s why in the opening we should try to bring the pieces as quickly as possible and on the best available fields (these are the central fields or fields from which the figure attacks the center of the board).

Why light, and because they enter the battle faster than rooks (they need open lines), and the queen because it is the strongest piece and in the beginning of the game it can be attacked by weaker pieces. The queen usually acts in conjunction with other pieces and delivers a decisive blow.

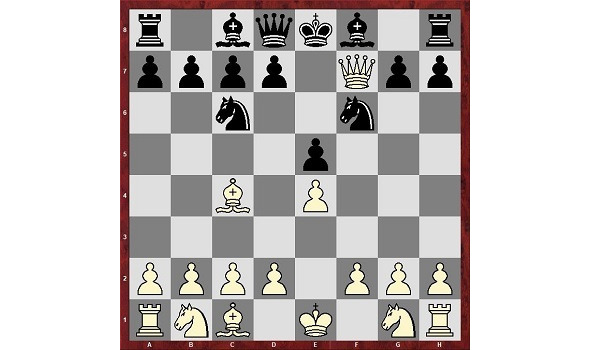

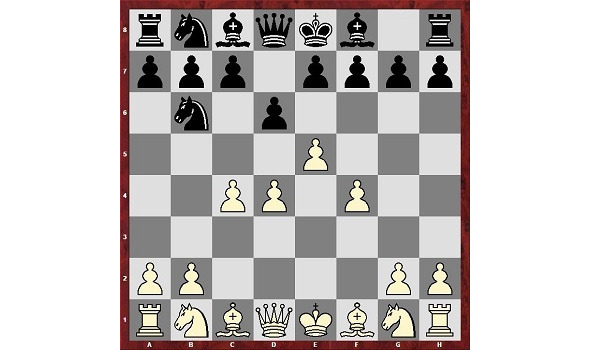

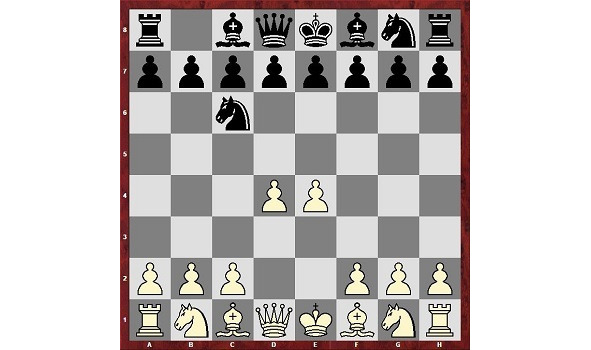

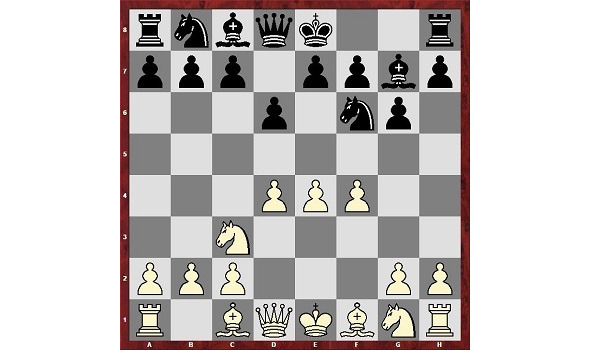

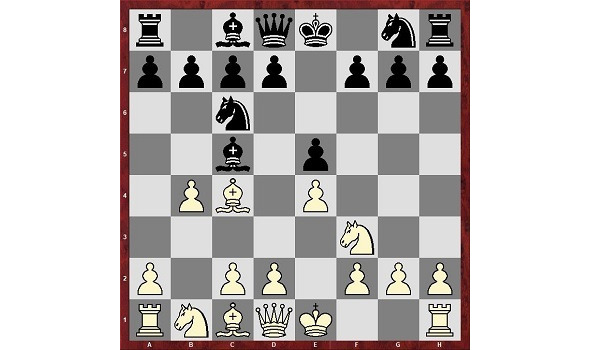

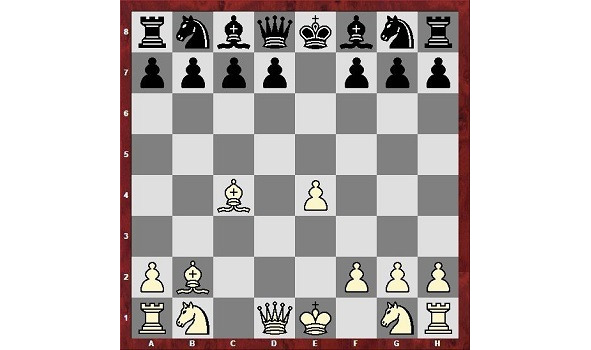

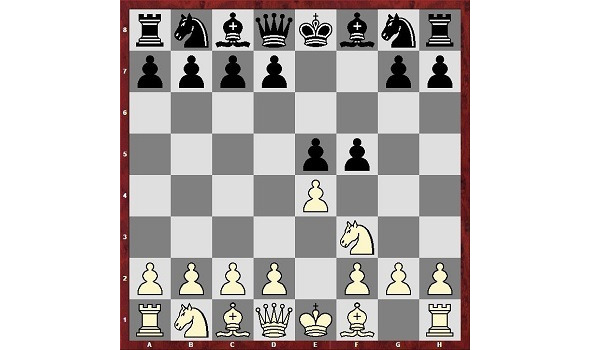

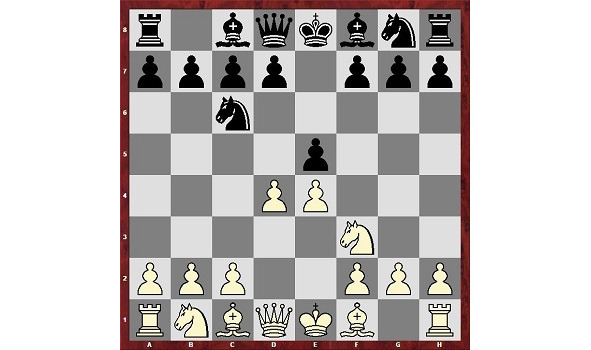

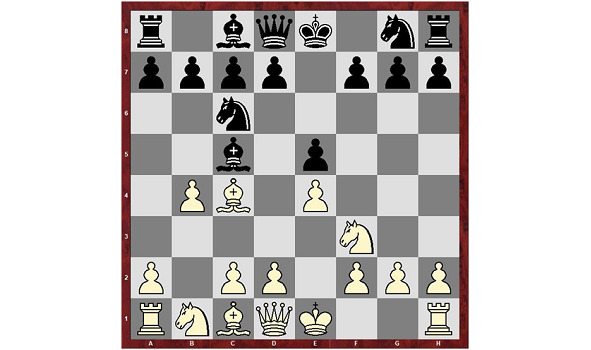

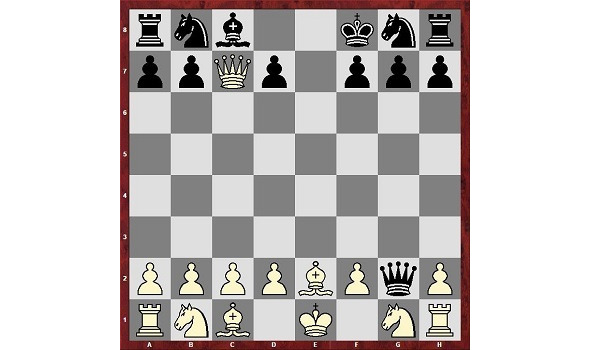

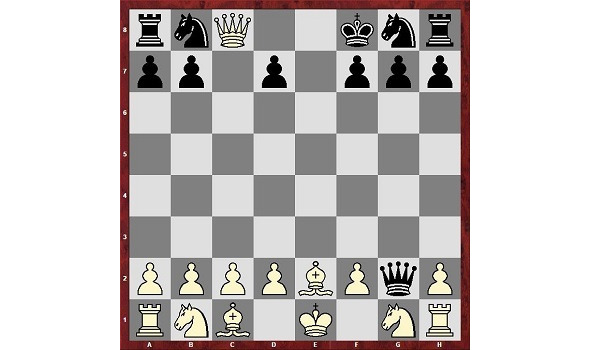

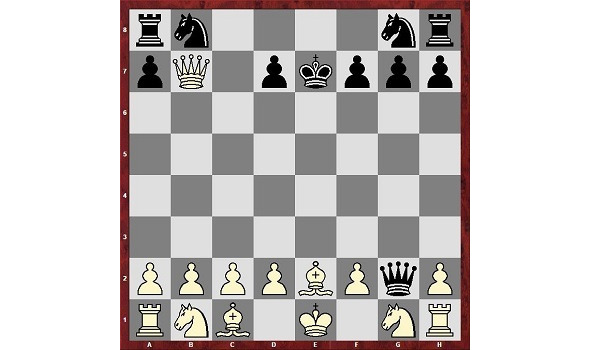

The approximate position of the pieces in the opening, which should be followed.

Look. The white pawns have captured the center, the light pieces are in active positions and control a very large part of the board, and they themselves are almost invulnerable. The bishops are targeting the opponent’s position from a distance, the knights are controlling the center with the support and cover of the pawns, and the rooks and queen are focused on the semi-open lines in the center of the board, ready to engage in battle and support the advance of the pawns.

A common mistake of beginners is to keep the king in the center for too long, or to start a pawn attack while the king is still vulnerable. Such actions can end badly (and if your opponent is experienced, it will happen necessarily), and you will quickly get lost.

Based on many years of experience in teaching chess players, I can say with confidence that 90% of novice players forget to castleboard. As a rule, after the development of the pieces, they get carried away with attacking and forget about their king. They always think that they are about to checkmate, or else they will have time to cast.

Although, in fact, castling is a very strong move, since it is the only move by two figures (unique in its kind) and, moreover, it usually ends development.

Checkmate in 2 moves and Legal’s checkmate. Why? To show the weakness of the f7 square (White’s f2 square is also weak, but not to the same extent, as White has the first move) from the very first moves. And Legal’s checkmate is a classic in chess, as White sacrificed their queen and achieved a beautiful checkmate with a knight. (If you are given the strongest piece, the queen, consider whether it is a “oversight” or a clever trap!)

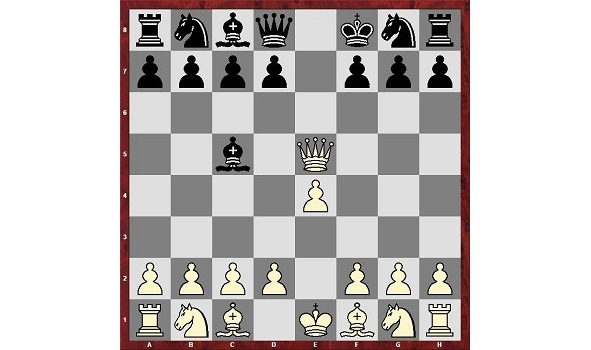

Checkmate in 2 moves 1.g4 e5 2.f3 Qh4#

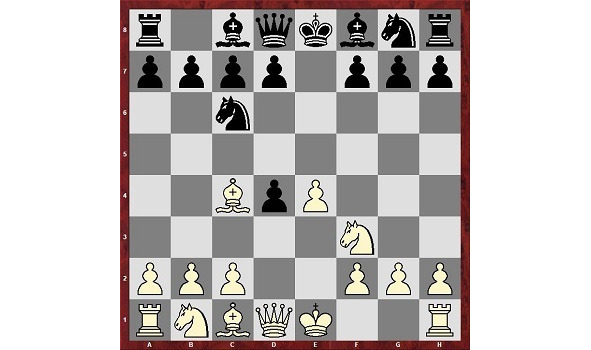

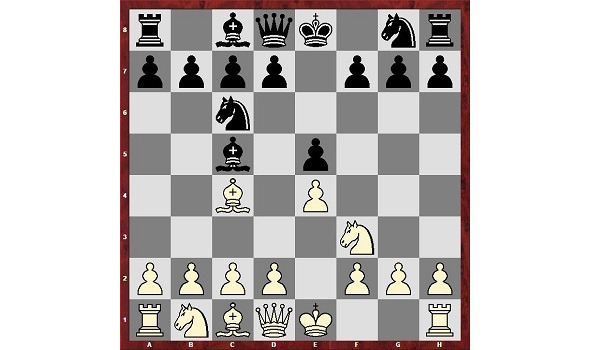

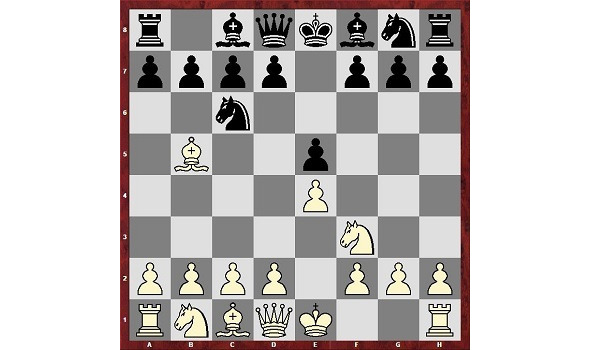

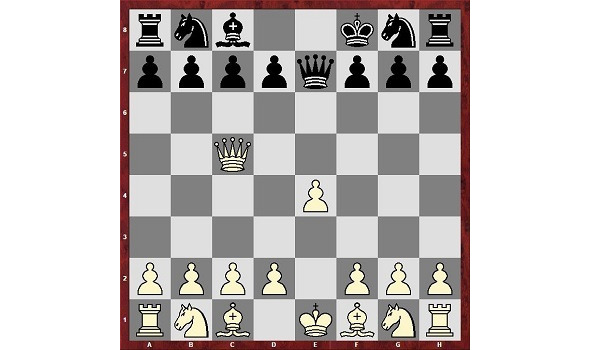

The famous Legal’s checkmate.

The Legal’s checkmate is a checkmate that was first encountered in the chess game between Legal — Saint-Brie in Paris in 1750.

1. e4 e5 2. Bc4 d6 3. Nf3 Nc6 4. Nc3 Bg4, then the Legal makes a deliberately erroneous move (Saint-Brie was a very weak player), opening the queen, which Saint-Brie uses without noticing the trick: 5. Ne5? B:d1?? (better it was 5. … Ne5!, after which White would have been left without a knight, or 5. … de, but after the move 6. Qg4, White had an extra pawn), Legal apparently knew well who he was dealing with… 6. Bf7+ Ke7 7. Nd5# — checkmate, which entered the chess literature by the name of the “discoverer” as “Legal Checkmate”. In this combination, the knight checksmate the opponent.

Simple rules of the game in the opening

1. Do not move the same piece twice unnecessarily.

2. Do not waste time (tempo) on moves with extreme pawns, it is more important to develop the pieces faster.

3. Do not bring out the queen prematurely.

4. Do not rush into a speed attack unprepared.

5. Do not engage in “chasing pawns”.

Remember that tempo in the opening is sometimes more important than a pawn!

Debut

Debut (opening classification, gambits), middlegame, endgame.

In chess, it is customary to divide the game into three parts: the opening, the middlegame and the endgame.

It is difficult to draw an exact line between these parts of the game in terms of the number of moves. The opening, middlegame, and endgame flow seamlessly into each other. And it doesn’t make any sense from a theoretical and practical point of view.

We all say debut, debut, so what is it?

début, literally translated from French, means the beginning, the appearance.

It is generally accepted that the duration of the opening stage is approximately 10 to 25 moves, depending on the variation.

Until the 20th century, most chess players preferred to play mostly open openings.

Gradually, openings were studied and new ones emerged. Many of them were named after the country where they were first used or the chess player who invented or significantly contributed to their development.

For example, the Alekhine Defense and the Nimzowitsch Defense. Spanish, Scottish, etc.

As the number of openings increased, they had to be classified over time. The classification is based on the development of the pieces.

In general, all openings are divided into

1. Open openings

2. Semi-open openings

3. Semi-closed openings

4. Closed openings

5. Flank openings

It is very difficult to distinguish between semi-closed, closed, and flank openings.

Therefore, we will stick to the classical classification

1. Open 2. Semi-open 3. Closed

Open openings.

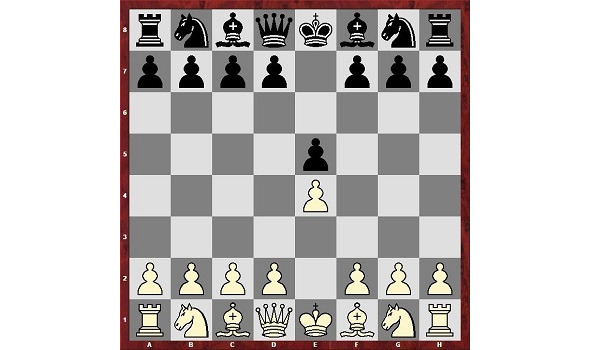

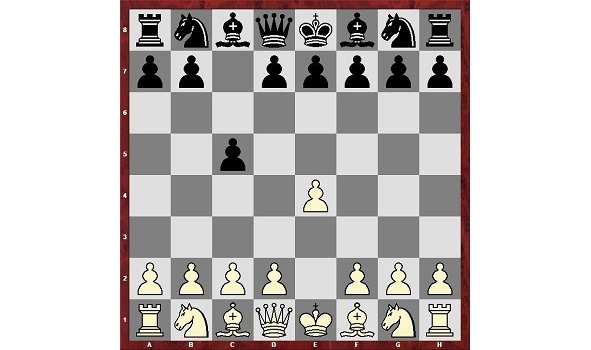

These are the oldest openings. White plays e2-e4, and Black responds with e7-e5.

Open openings appeared more than 500 years ago. Until our time, they were the most popular, but even now their popularity is very high, especially among novice chess players, and it is on them that we will pay special attention a little below.

What characterizes open openings? First of all, the rapid development of all figures, opening the center and attacking the king.

List of open openings

Parham’s Attack

Hungarian Game

Vienna Game

Blackburn’s Gambit

Rousseau’s Gambit

Urusov’s Gambit

Alapin’s Opening

Vorotnikov’s Opening

Constantinopol’s Opening

King’s Pawn Opening

King’s Knight Opening

Napoleon’s Opening

Pontziani’s Opening

Bishop’s Opening

Three Knights Opening

Four Knights Opening

Protection of Greco

Protection of Gunderam

Damiano’s Defense

Protecting 2 Knights

Protection of Philidor

The Spanish Party

The Italian Party

The King’s Gambit

The Latvian Gambit

The Russian Party (Petrov’s Defense)

The central opening

Central countergambit

The Scottish Party

The list is large, but mostly played by: Hungarian Party,

Vienna Game, Four Knights Opening, Two Knights Defense, Philidor Defense, Spanish Game, Italian Game, King’s Gambit, Russian Game, Central Opening, Scottish Game.

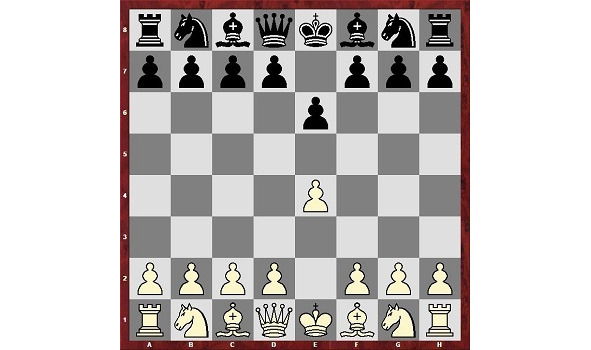

Semi-open openings.

Black can respond to e2-e4 with any move except e7-e5.

Semi-open openings are characterized by the fact that Black cedes the central squares and makes other positional concessions, and in return, they gain the opportunity for active counterplay.

The popularity of semi-open openings lies in the fact that there are more defensive systems for Black than in open openings, plus the opportunity for counterplay, which means that Black can play for a win.

The most popular opening in semi-open openings is the Sicilian Defense.

List of semi-open openings

Nimzovich’s Opening

Alekhine Defense

Caro-Kann Defense

Pirc-Ufimtsev Defense

Sicilian Defense

Scandinavian Defense

French Defense

Owen Defense

St. George Defense

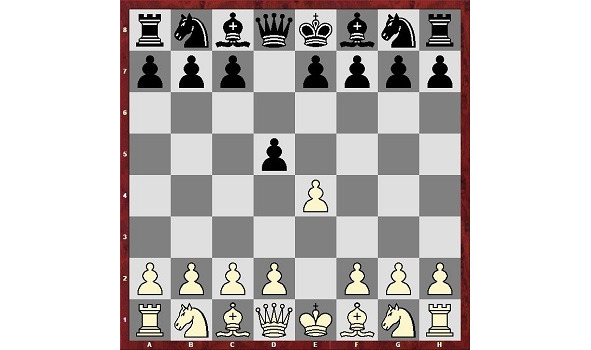

Closed openings.

When White plays any move other than e2-e4.

The 20th century was characterized by a revision of the entire opening theory, and closed openings became popular. The Queen’s Gambit became the most played opening. The Queen’s Gambit became dangerous. Other openings were developed against it, such as the King’s Indian Defense, the Grünfeld Defense, and the Nimzowitsch Defense.

With the introduction of closed openings, the importance of controlling the center and quickly developing pieces diminished. Closed openings are characterized by the refusal to immediately advance the central pawns, figurative pressure on the center, flank development of the bishops, and then pawn undermining.

List of Closed Openings

Chigorin Variation

Blackmar-Dimer Gambit

Dutch Gambit

Queen’s Pawn Opening

Ragozin Defense

Tarrasch Defense

Chigorin Defense

Catalan Opening

Albini Counter-Gambit

Vinawer Counter-Gambit

Refused Queen’s Gambit

Accepted Queen’s Gambit

Slav Defense

Queen’s Gambit

Gambit — (from Italian. gambetto — footstool) — a common name for openings in which one of the parties in the interests of faster development, capture of the center or simply to sharpen the game sacrifices material (usually a pawn, but sometimes a piece).

Gambits were very popular in the 19th, early 20th century, in the era of the heyday of combinational attacking game.

The meaning of a gambit: victory is not in numbers, but in skill.

A brief overview of gambits

Gambits in open openings

The King’s Gambit 1.e4 e5 2.f4

This is probably one of the oldest gambits, and it is still relevant today.

The idea behind the pawn sacrifice is that:

White captures the center with the d4 move and quickly develops their pieces.

After a short castling and the capture of the black f4 pawn, White gains the opportunity to attack the f7 square along the f-file.

The main disadvantage of the 2.f4 move is that it weakens the position of the white king. On the third move, there is a threat of checkmate with the queen on h4, and a material advantage with a pawn.

From the very first moves, an interesting and intense struggle begins, requiring attention and precise calculations from both sides.

Evans Gambit 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb4 Bc5 4.b4

This is a very interesting gambit that offers great opportunities for attack and counterattack.

The Scottish Gambit 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 ed 4.Bc4

The Northern Gambit 1.e4 e5 2.d4 ed 3.c3 dc 4.Bc4 cb 5.Вb2

White sacrifices two whole pawns.

Gambits in semi-open openings

Sicilian Gambit 1.e4 c5 2.b4 cb 3.a3

Morra’s Gambit 1.e4 c5 2.d4 cd 3.c3 dc 4.Nc3

Albin Countergambit 1.d4 d5 2.c4 e5 3.de d4

By sacrificing a pawn, Black slows down the development of White’s pieces. Additionally, the e5 pawn is weak and usually gets recaptured.

Volga Gambit 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 c5 3.d5 b5 4.cb a6

This is a popular gambit for Black. The idea is purely positional — to organize pressure on the queen’s flank along the open lines “a” and “b” with the support of the bishop g7.

Blumenfeld Gambit 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nf3 c5 4.d5 b5

In terms of ideas, it is similar to the Volga Gambit.

Countering Gambits

In his time, the second world chess champion, Emanuel Lasker, suggested a way to deal with gambits: instead of holding on to the material advantage, return it at the first opportunity. This is done to regain the initiative or simplify the game. As a result, many gambits have lost their relevance.

There are three ways to respond to a gambit:

1. Accept the sacrifice and accept the gambit.

2. To reject a sacrifice – rejected gambit.

3. To offer a counter-sacrifice to a proposed sacrifice — counter-gambit.

Is it necessary to play gambits? Yes! Absolutely! Especially at the initial level of mastering chess. But it is advisable to apply them in training parties, blitz, in responsible competitions for the application of gambits, sufficient experience is required (which is not yet, unfortunately).

You will ask then why to play them? I answer: the fact is that gambit ideas are used much more often than the gambits themselves.

In gambits, tactical vision of the position is trained, the prerequisites for a possible combination are created, and, among other things, in gambits, it is most often possible to distinguish victims from yawns (because the opponent deliberately gives a pawn or a piece).

The list of gambits is much more than we have shown. I have named the most relevant and frequently used.

Try to prepare and play a gambit with your familiar chess player, and you will see how the opponent hesitated or even got into a stupor. And all because the opponent has to solve urgent problems from the very first moves. Especially if he hasn’t played the gambit yet.

The victim needs to make an instant decision about whether to accept or reject the offer, and what will happen next, and so on, and all of this takes time.

Mittelspiel

Mittelspiel (from German. Mittelspiel — the middle of the game) — the next stage of a chess game after the opening, in which, as a rule, the main events in the chess struggle — attack and defense, positional maneuvering, combinations and sacrifices develop. This stage of a chess game, which is characterized by a large number of figures and a variety of plans of the game. Sometimes a chess game passes this stage of the game and immediately goes to the endgame.

The Mittelspiel

Most chess players grasp how to act in the opening quite quickly. However, they do not have a clear idea of how to play in the middlegame. This is due to the fact that the middle of a chess game is the most difficult part, and it is impossible to rely on simple tips such as developing pieces and making a quick castling.

14 important principles of playing in the middlegame

1. The struggle for the center. Dominance in the center is beneficial

In chess, a player usually has an advantage if they control the center. Control of the center provides additional space, which in turn gives the pieces good positions. This fact is very important for both attack and defense. The struggle for the center is a crucial element in positional chess.

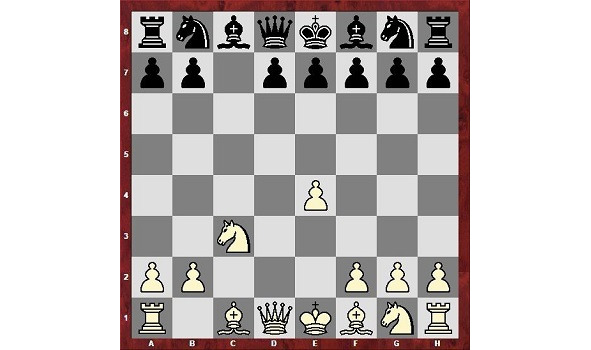

2. Centralize your pieces

Centralized pieces gain more importance in a chess game. This is especially true for knights, which control 8 squares in the center and only 2 on the edge of the board. In this sense, bishops are long-range pieces, but they can work on both flanks from the center. The same applies to queens.

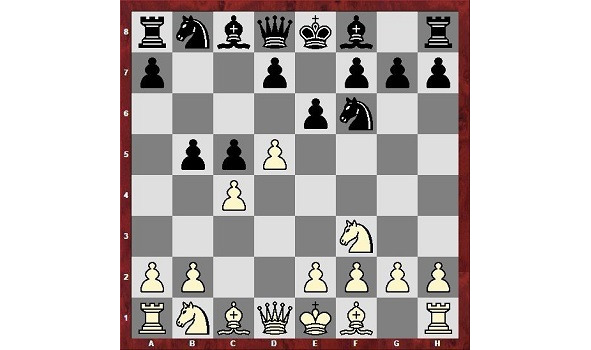

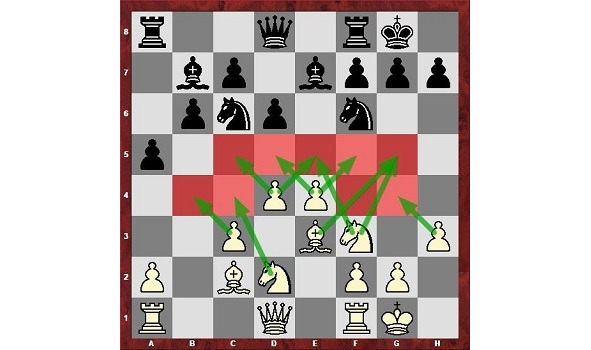

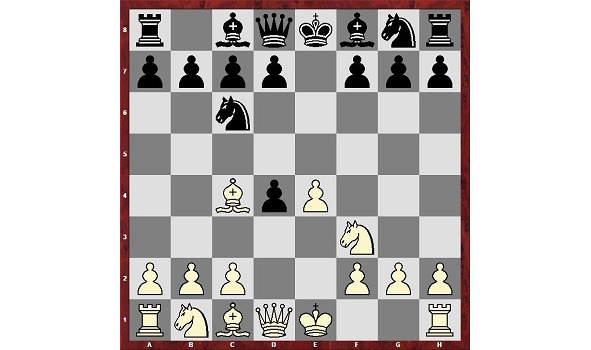

White has brought 4 of its pieces to the center. In the next move, it is ready to move its knight to e5. This knight in the center cannot be tolerated, and if Black trades, the white bishop will move to e5, targeting the black king.

3. Use outposts for the knight

An outpost — is a field in the opponent’s camp that is not controlled by any of their pawns. This field becomes particularly valuable if it is occupied by a knight. Knights are especially strong near the center of the board and near the opponent’s king.

The knight on the outpost restricts the opponent’s pieces. You gain space, reduce the mobility of their pieces, and create new threats.

4. Avoid moving pawns in front of the king

As a rule, you should avoid moving pawns in front of the king. This weakens the king, opens up the diagonals and creates a lot of unprotected squares, because of this dangerous threats are created. Of course, there are exceptions to this rule, where the movement of pawns is favorable (for example, when the center is closed, but about this later).

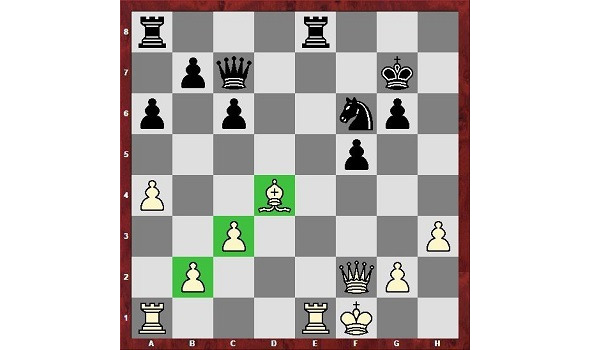

5. Exchange pawns towards the center

In most cases, central pawns are stronger than flank pawns, because they can control the most important squares (d4-d5-e4-e5). On these squares, the pawns support their own pieces and push back the opponent’s pieces, capturing space. Therefore, it is almost always necessary to exchange your pawns towards the center.

Example:

Here, White needs to play fe in order to create a powerful center with the c-d-e pawns. Additionally, the f-file is opened for the rook, which was previously inactive (the rook on d1 is already in an active position and will help promote the pawns).

6. Avoid pawn weaknesses (we will discuss strong and weak pawns in more detail later)

When pawn weaknesses appear, a simple plan for attacking these weaknesses also appears. Pawn weaknesses become increasingly obvious as the game approaches the endgame. Why is this the case?

Because as pieces disappear from the board, it becomes increasingly difficult to compensate for damaged pawns (such as attacking the king or advancing a passed pawn). Conclusion: it is necessary to carefully approach every change in the pawn structure and avoid weakening it unless there are other benefits.

In this position, both sides have pawn weaknesses. White has doubled pawns on the kingside and a backward b2-pawn. Black has isolated pawns on the queenside.

7. Avoid weak squares in the position

Weak square (also weak point) is a square that cannot be defended or attacked by a pawn. Is one of the key concepts in chess strategy and tactics. Such squares become excellent outposts, so as soon as weak squares appear, immediately try to send your pieces there. It is especially dangerous to create weak squares in the center of the board or near the opponent’s king.

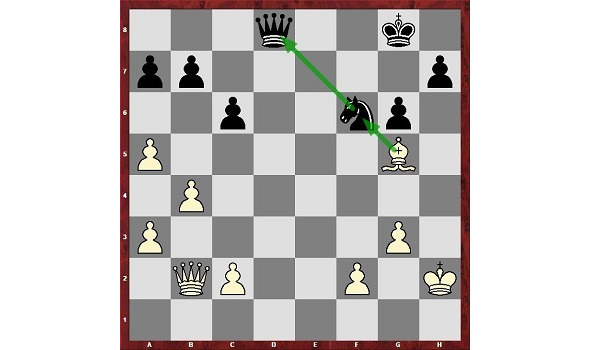

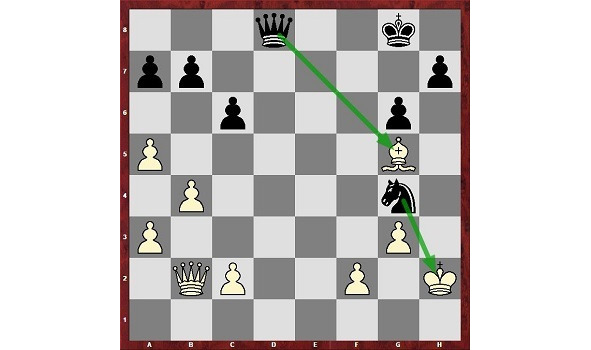

In the diagram, Black has a weak f6 square, which is located near the king’s position. The white knight can move there, followed by the pawn, creating checkmate threats with the support of the queen.

8. Block an isolated pawn with a knight

An isolated pawn can be both a weakness and a strength. It often supports pieces that attack the king. Additionally, an isolated pawn can move forward if its movement is not blocked. It is best to block a pawn with a knight, because the knight controls many squares in front of the pawn, and since the knight can jump over pieces, it can control squares by hiding behind the enemy pawn like a fortress and attacking from there. Additionally, the knight is not as valuable. Blocking with a queen is less effective, as the queen will have to retreat if attacked by any other piece.

And vice versa, if your isolated pawn is blocked, you need to destroy this piece (in this case, the knight). In the position, the knight on e3 blocks the black pawn and controls the important squares c4, g4, d5, and f5.

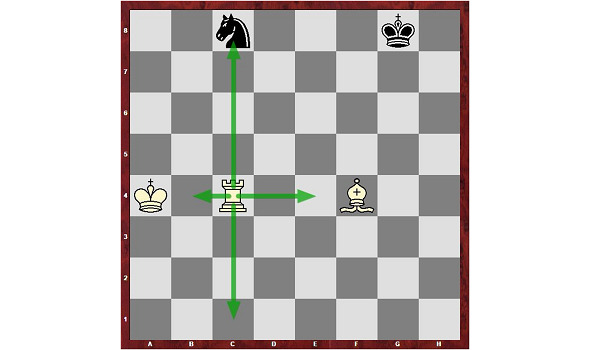

9. Occupy open verticals with rooks

Rooks like open and semi-open lines

Rooks usually become very strong when:

1. They are placed on open lines

2. They are connected

3. They are doubled

A rook protects its position from enemy pieces and can try to invade the opponent’s camp. If there are open or semi-open lines, they should be occupied with rooks as quickly as possible.

Then, you need to double the rooks along the open vertical.

White has captured the “c” rank, which gives them an advantage. Black cannot place their rook on c8 to prevent White’s invasion on c7. To counter the invasion threat, Black must play their knight on e8, which ties up their other pieces.

Bishops

10. The bishop should be placed in front of the pawn chain

The bishop is a long-range piece. In open positions, the bishop controls more squares than in closed positions, making it more powerful. To make the bishop stronger, it should be placed on the open diagonals in front of the pawn chain. Placing the bishop behind the pawn chain is undesirable, as it reduces its strength.

11. Try to keep a pair of bishops

This is called the advantage of two bishops. In open positions, a pair of bishops is a very formidable force. They control a large area, and their value is low, which allows them to attack the opponent’s heavy pieces.

White bishops literally shoot through the center and the kingside, unlike the black knights, which have almost no control. With the support of their bishops, White can start advancing their pawns, such as f4 and then f5 or e5.

12. Avoid exchanging the fianchettoed bishop with your king’s castling (it is a powerful defender).

As a rule, it is not profitable to exchange a royal fianchettoed bishop, as this seriously weakens the king’s defense and makes it more vulnerable. A fianchettoed bishop near the king is a strong defensive piece. It controls many important squares that immediately become weak if it is removed. Therefore, it is important to plan your game in a way that allows you to keep this bishop for as long as possible.

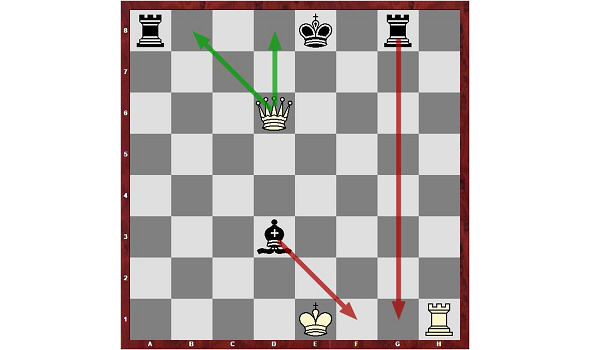

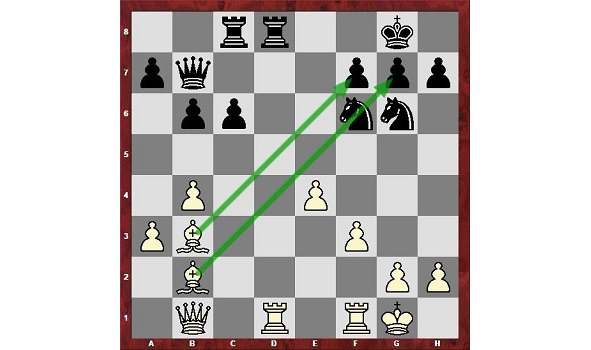

13. Creating weaknesses in the opponent’s camp

Manoeuvring (chess) — maneuvering pieces in order to create and use weaknesses in the opponent’s camp. A strategic technique. The term was proposed by Aron Nimzovich.

White played 1.Ng5 g6 2.Ne4

It turned out that Black had a whole set of weaknesses in his king’s defense.

1 … Nd4!

The idea of the diversionary sacrifice is clear: if 2. N:d4, then 2. … Qh2#. Threatens 2. … N:f3+ with checkmate. White has no choice.

2. hg N:f3+3. gf Qg3+4. Кh1 Q:h3+5. Kg1 R:f3

With the idea 6. … Rg3X.

6. Q:f3 Q:f3, and after 3 moves, White resigned.

14. Try to anticipate your opponent’s threats

Anticipating your opponent’s moves is a crucial skill, both in attack and defense. By understanding your opponent’s plan, you can eliminate or at least reduce their threats. If you identify these threats early enough, most losing combinations (such as forks, ties, and checkmate networks) can be avoided.

To do this, you need to learn how to count options.

For example: if I go Rd8+, will it be a checkmate? No, he will close with a rook, and then I will eat his rook, which one? He will also eat my rook, and then I will go Ld7 and attack the pawn. How will he defend it, will he go La8 or move the pawn forward? And so on.

EXAMPLES AND EXERCISES ON OPTIONS in separate applications *

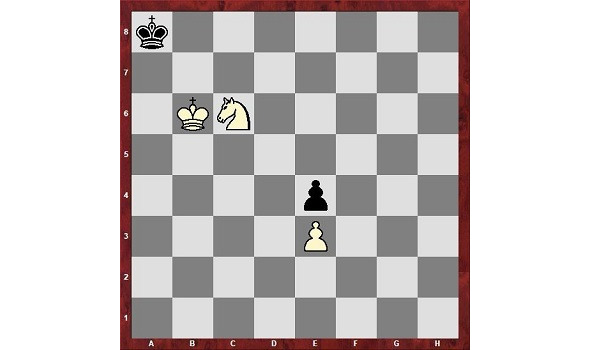

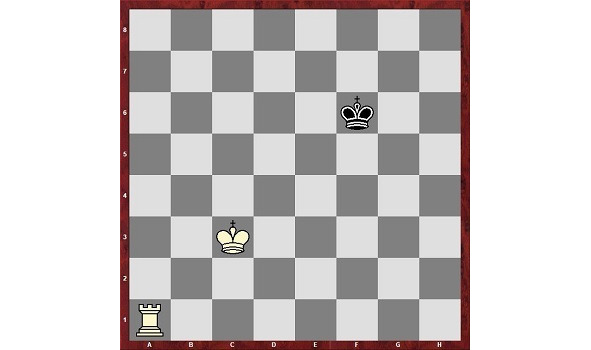

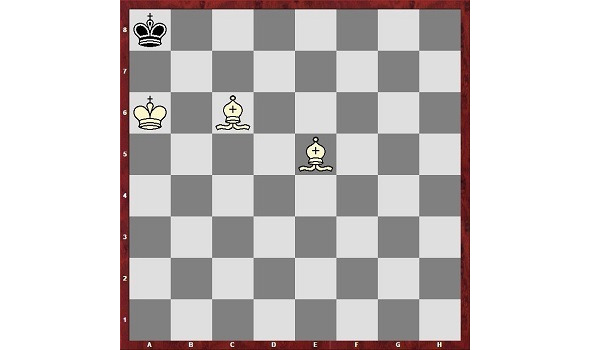

Endgame

Endgame (from German. Endspiel — “final game”) is the final part of a chess game, after most of the pieces have been exchanged. As a rule, in the endgame, the main task is not to put a checkmate, but to lead a pawn to the queen, and thus achieve a decisive material advantage.

It is not always possible to draw a line between the middle game and the endgame. Usually, the game goes into an endgame when most of the pieces have been exchanged and there are no typical mid-game threats to the kings. However, the absence of queens on the board is not a mandatory feature of the “Queen Endings” endgame.

Usually, in the endgame, there is no longer a plan to prepare and carry out an attack on the king. Instead, the endgame often involves a strategic goal of promoting a pawn to queen in order to gain the material advantage necessary for victory.

The endgame is characterized by the following key features: The king in the endgame is an active piece. As long as it is not threatened by a checkmate, it can leave its hiding place and participate in the battle alongside other pieces. It can attack the opponent’s pieces and pawns and lead the charge into the enemy’s camp. The approximate strength of the king in the endgame is the strength of the rook.

Your king should not hide in a shelter in the endgame, as this is a direct path to defeat.

This can be described as a “residual effect” from the middle game, where the king needed protection. When transitioning to the endgame, it is important to mentally reconfigure, as the game is completely different (one could even say diametrically opposed) at the end of the game compared to the opening and middlegame.

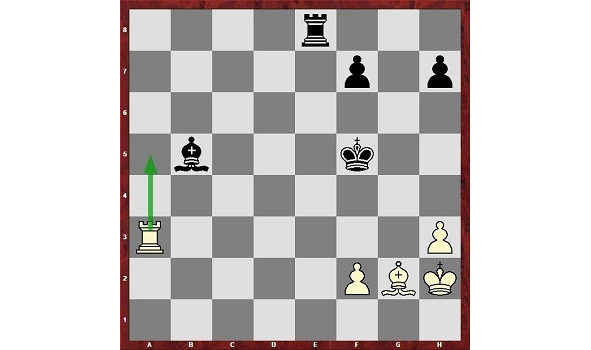

Black has an extra pawn, but the white king is more active. The result of the match is predetermined, because nothing can prevent the white pawn a5 from becoming a queen.

The value of pieces

There are few pieces in the endgame, so the value of each piece increases. While creating a decisive advantage on a particular part of the board is often enough to win in the middle game, playing the endgame correctly means ensuring maximum activity and clear interaction between the pieces.

Pawns

In the endgame, the role of pawns increases dramatically, as the chance of promoting a pawn to queen increases.

While a one-pawn advantage in the middle game is usually not decisive, it is often sufficient for victory in the endgame.

In the middle game, the plan is often determined not only by the position, but also by the opponents’ playing style, psychological calculations, and so on.

In the endgame, the game plan focuses on achieving specific positions that are known to be valuable.

For example:

RECOMMENDATIONS

You don’t need to play all the openings in a row, there’s no need for such a spread.

(Even in one opening, there is enough information to last for many years).

So, you and I have decided that we need to play open openings first, based on this, it follows:

1. Make up a debut repertoire for yourself (what you will play) for whites and for blacks.

For White, 2—3 openings are enough, this is in response to 1…e5

If you are going to play

Italian Game 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5

in addition to the Italian Game itself, you can be played for Black:

2-Knight Defense 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Nf6

Philidor Defense 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 d6

Hungarian Game 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Be7.

The Russian game is 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nf6.

The Latvian Gambit 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 f5 is played extremely rarely, but you should know at least one correct answer.

If you are going to play

The Scotch Game 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. d4.

(in addition to the Scottish Game itself, you can be played for Black: Russian Game, Latvian Gambit).

Gambits

Be sure to include gambits in your opening repertoire to choose from:

King’s Gambit 1.e4 e5 2. f4

Scottish Gambit 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 ed 4.Bc4.

Evans Gambit 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.b4

Gambits not only help you master typical tactical strikes, but also give you an understanding of what tempo, initiative, material superiority, etc. are.

If you are not playing 1…e5, you should also know at least one variation of the most popular semi-open openings:

The Sicilian Defense

The French Defense

The Scandinavian Defense

The Caro-Kann Defense

The Pirc-Ufimtsev Defense.

Pirc-Ufimtsev Defense. Modern variant.

The Sicilian Defense 1. e4 c5. is the most popular semi-open opening

The French Defense 1. e4 e6 is the second most popular semi-open opening

Scandinavian Defense 1. e4 d5.

Caro-Kann Defense 1. e4 c6.

Pirc-Ufimtsev Defense. Modern variant.

1.e4 d6 2.d4 Nf6 3. Nc3 g6.

For Black, for now, limit yourself to openings with moves on 1.e4 e5

On 1…e5, you should be prepared for openings such as:

King’s Gambit, Scotch Game, Scotch Gambit, Vienna Game.

Vienna Game 1.e4 e5 2.Nc3.

Four-Knight Opening 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Nc3 Nf6.

Central Opening 1.e4 e5 2.d4 ed

Ponziani’s Opening 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.c3.

Spanish Game 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 is the most popular open opening

on 1.d4, play 1…d5 Refused Queen’s Gambit (the pawn sacrifice by White in the Queen’s Gambit is quite conditional, as if Black accepts the sacrifice, there is no need to defend it, as it would put White in a very unpleasant position (unlike the King’s Gambit, where the pawn can be defended in some variations).

If white is not playing 1.e4 or 1.d4 with you, then proceed from the general rules of playing the opening (you will not give recommendations for all moves) Center. Development. Castling. And if possible, reduce the game to the opening schemes you know.

For example:

1.Nf3 e6 2.d4 d5 3.c4 Nf6 or 1.c4 e6 2.Nf3 d5 3.d4 Nf6

with the reordering of the moves, it is possible to obtain a position from the Queen’s Gambit.

(Today, powerful computer programs have made significant adjustments to the game of chess, but we will discuss this later in the book).

However, it is up to you to decide, as each chess player chooses their own opening repertoire based on their preferences and interests.

But again, this is just the first step in learning opening preparation and as a rule with the improvement of qualifications, each chess player rethinks the opening repertoire for himself.

What is closer to him a quiet beginning in closed games or an open uncompromising struggle, associated with a certain risk, symmetrical positions, or attacks on the flank, etc. etc.

Experienced chess players always have several well-studied openings (or variations) in reserve, both for White and for Black.

This is because it is crucial to consider the opponent, the desired outcome, and the color and moves of your opponent. For example, if you’re playing black against a slightly weaker opponent and they play 1.e4, it might be worth considering not playing 1…e5 and instead playing 1…c5 or 1…e6, which is a semi-open opening, and so on. However, this is something that experienced players do.

At this stage, one opening is sufficient, and everything comes with experience.

Chapter 3

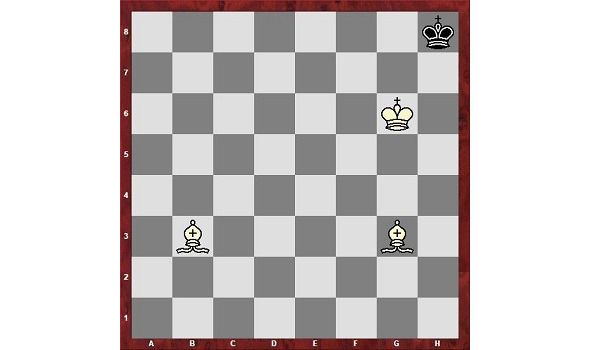

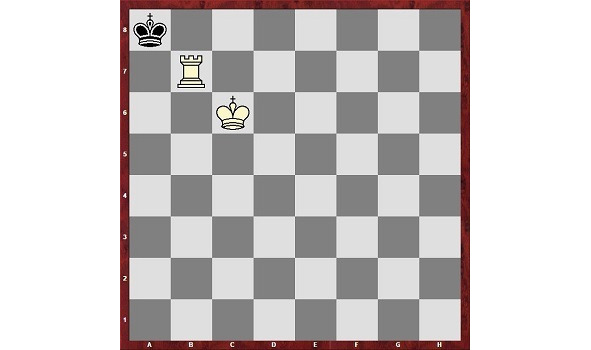

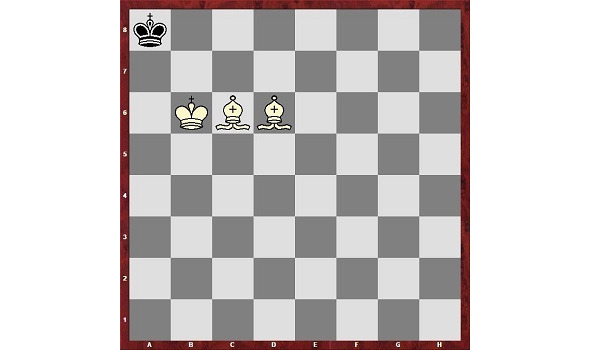

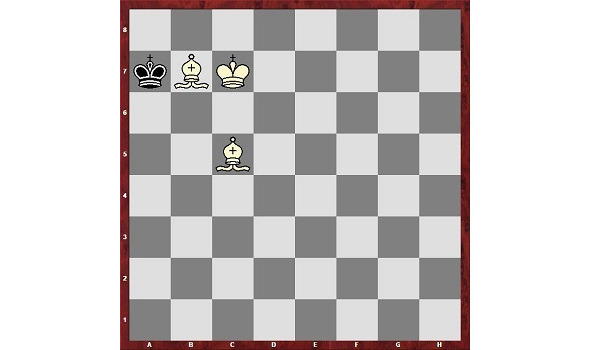

Mate with heavy pieces. Mate with two bishops. Typical mates (king with a piece and pawns, queen with a piece, rook with a piece, stifled mate). Key fields, time pressure, zugzwang. Appendix 3.1 Basic Mate Structures

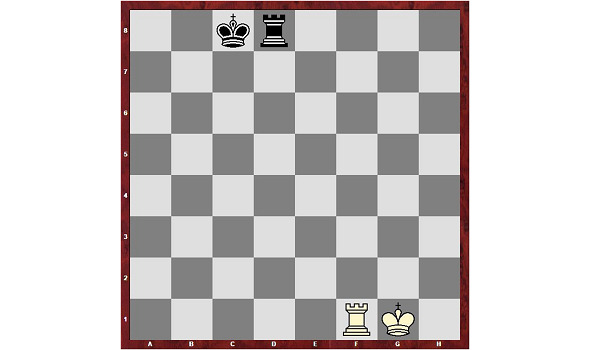

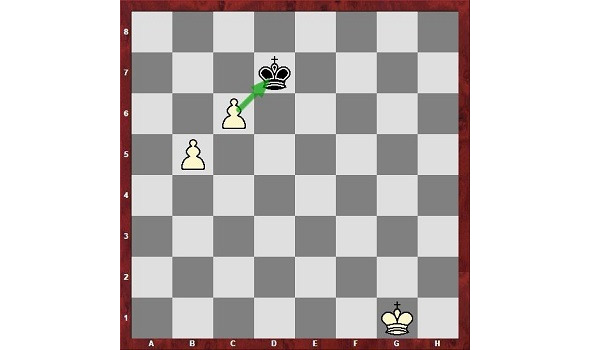

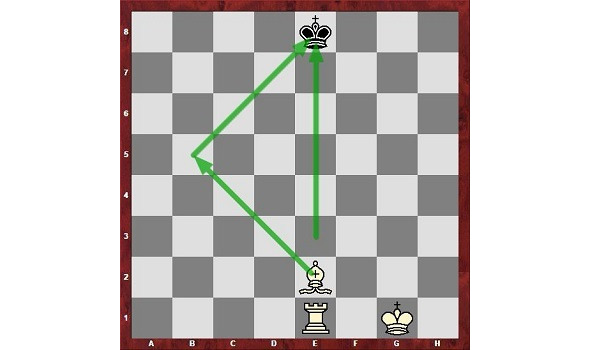

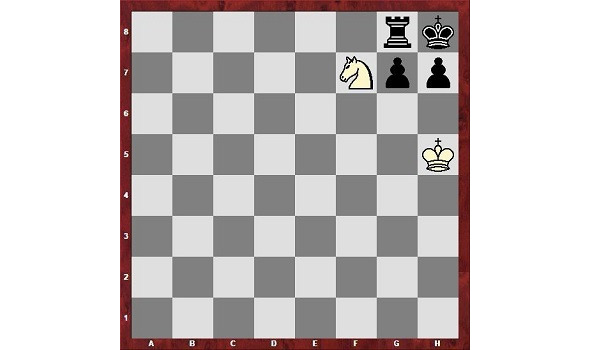

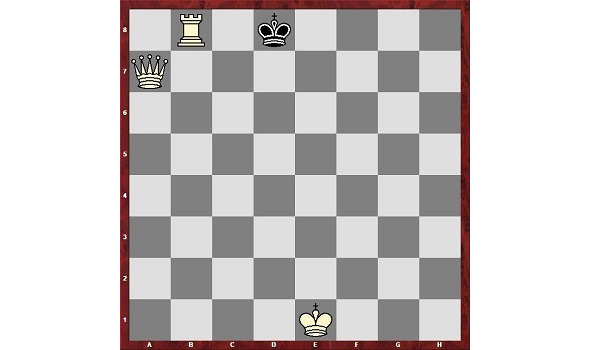

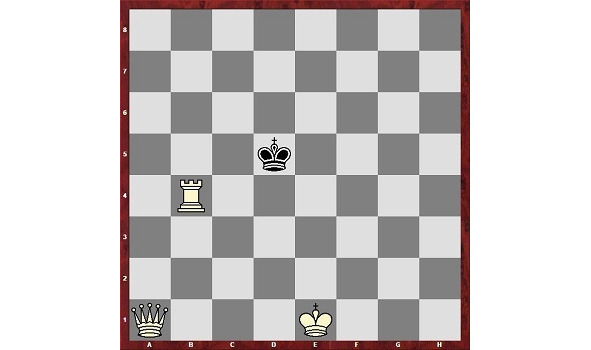

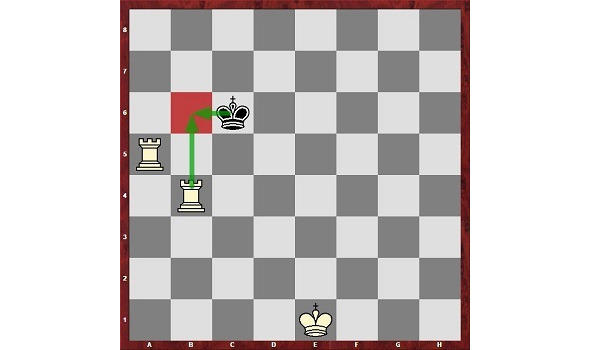

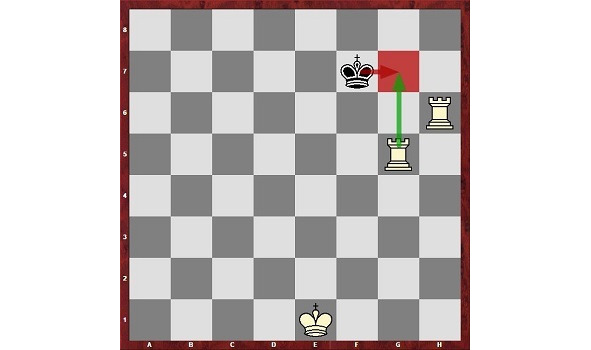

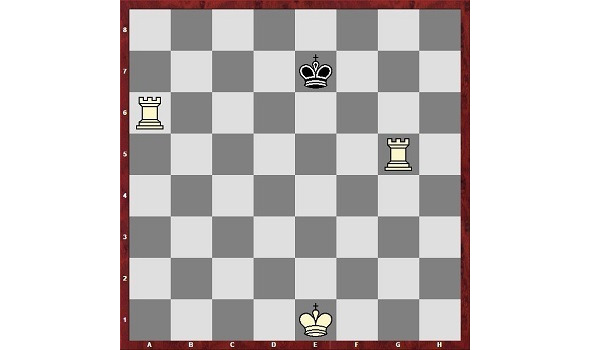

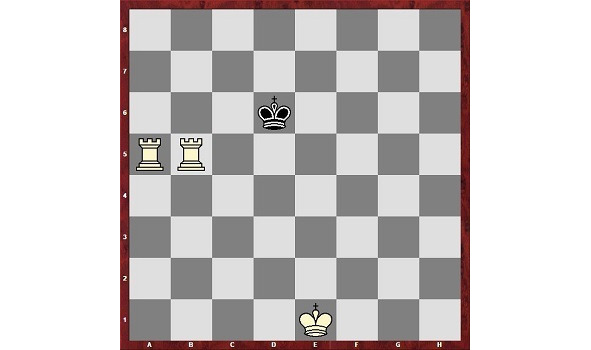

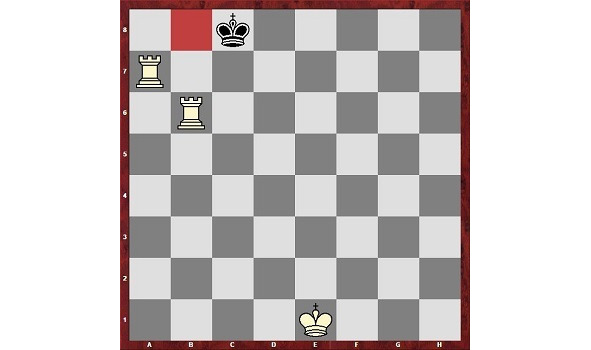

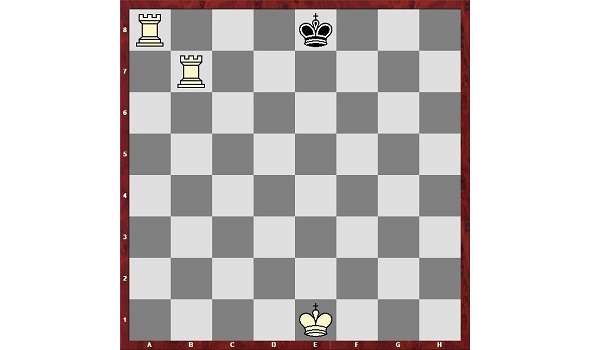

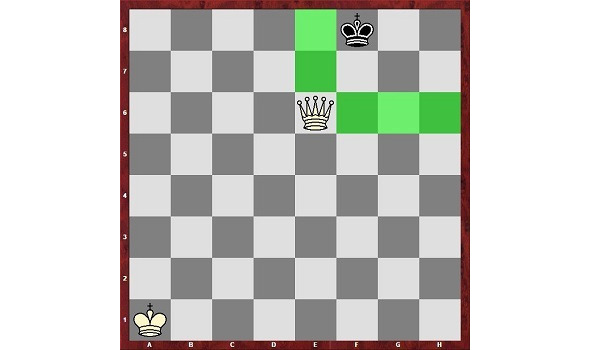

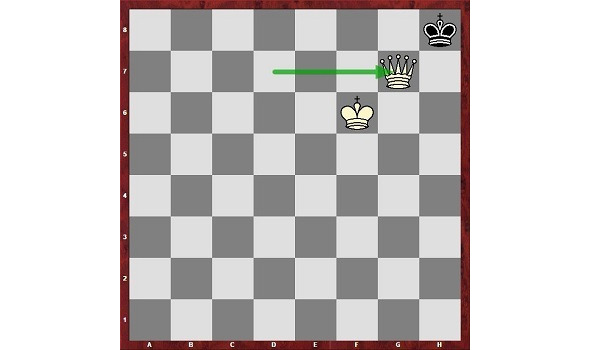

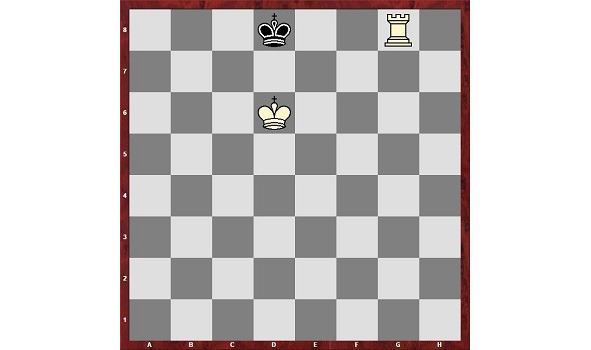

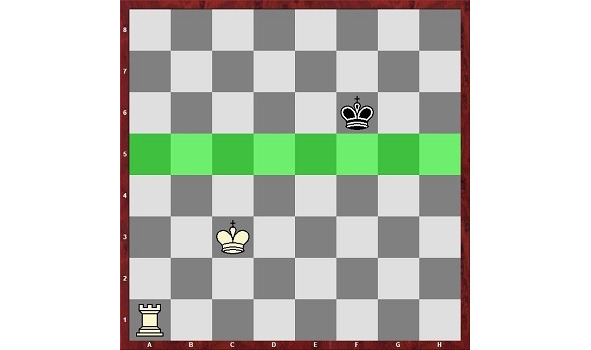

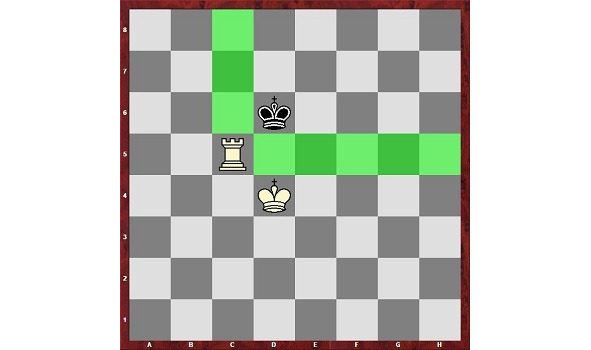

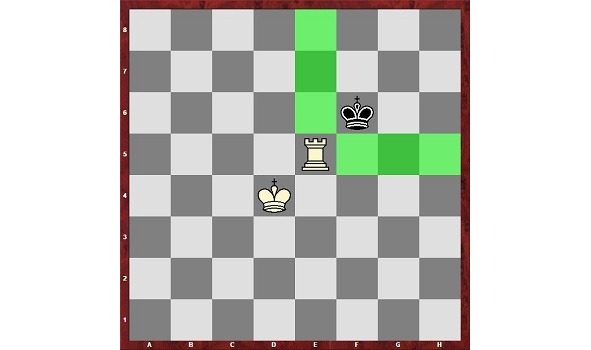

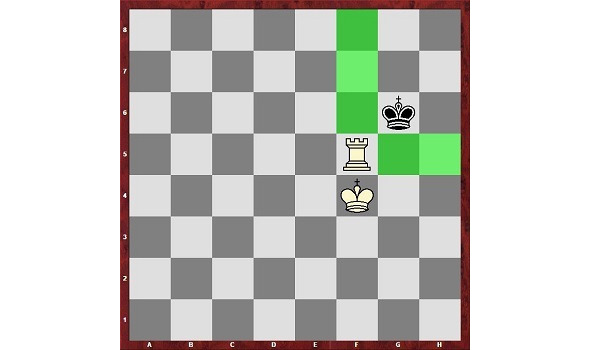

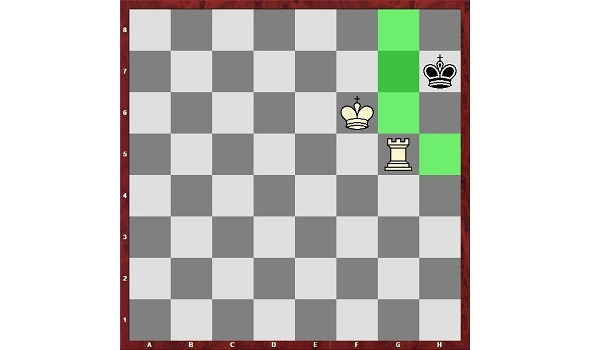

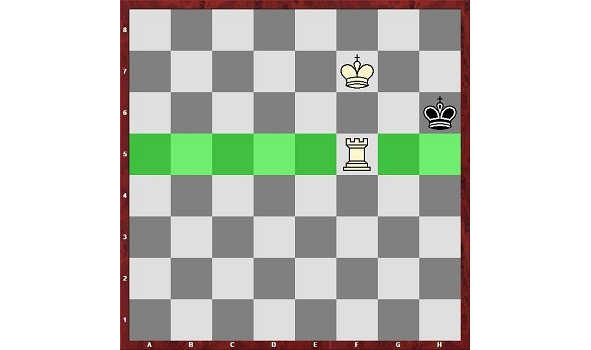

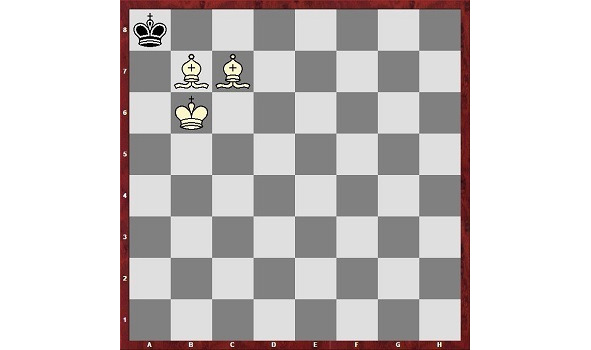

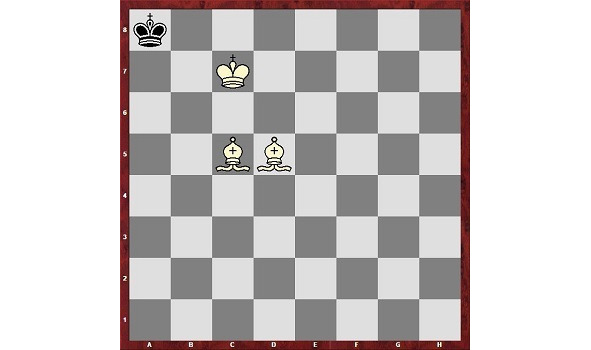

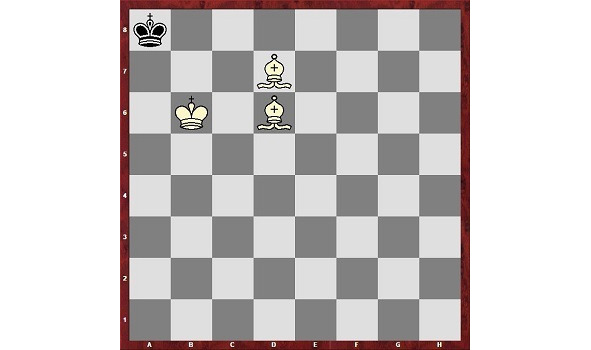

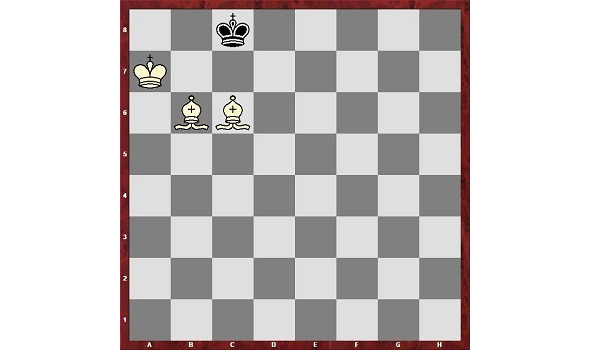

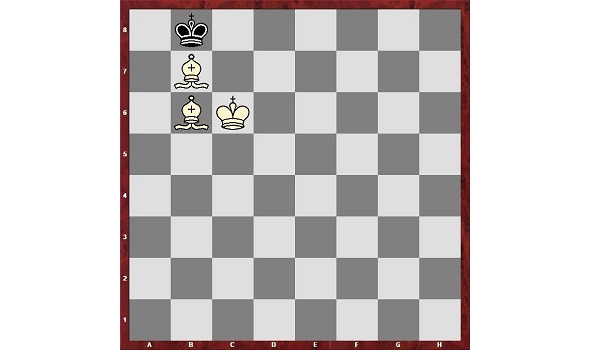

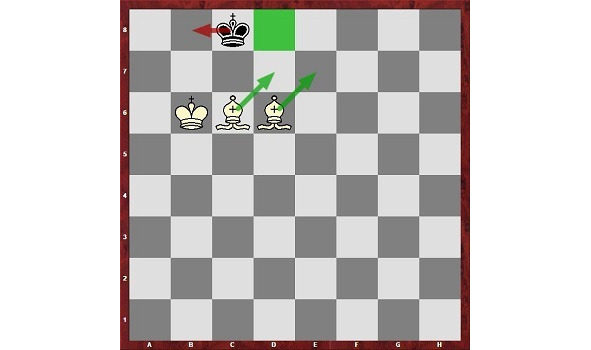

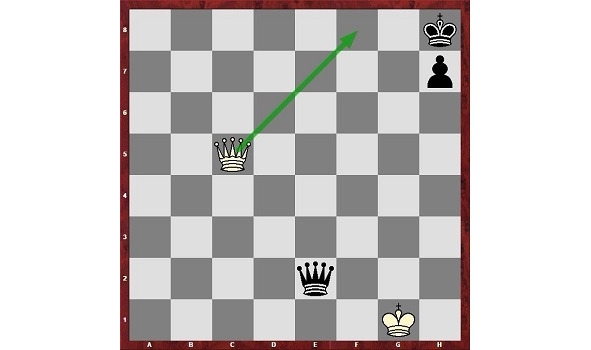

Checkmate with heavy pieces. Linear checkmate

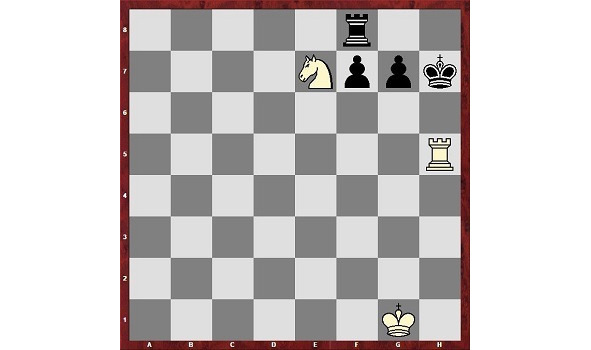

Linear checkmate, checkmate with heavy pieces, usually two rooks (less often a rook and a queen, two queens).

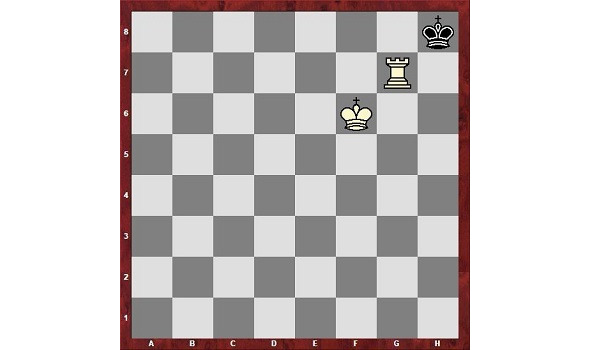

Checkmate with a queen and a rook.

How to checkmate with a queen and a rook?

The ultimate goal of a chess game is checkmate. We will consider the so-called linear checkmate. Why is it called linear? Because it is achieved with heavy pieces along lines (vertical or horizontal).

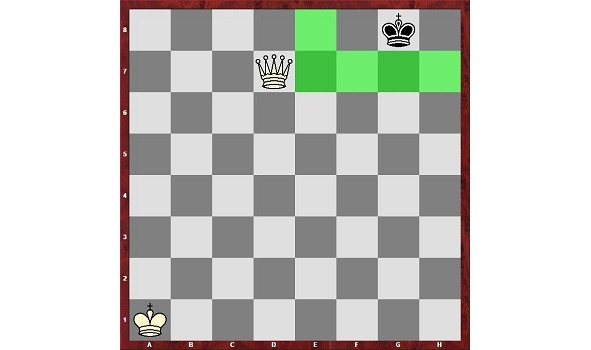

Checkmate is placed on the edge of the board, so you first need to determine which edge of the board the opponent’s king is closest to. This is necessary to place the checkmate as quickly as possible.

Many novice chess players ignore this rule (they believe that no matter what the difference is between a move earlier and a move later, checkmate is inevitable anyway). Checkmate is inevitable, of course, but… what if you run out of time and then it’s an insulting draw (according to the rules, if you run out of time and your opponent doesn’t have enough material to checkmate, then a draw is awarded).

But the most important thing is not that, but that it becomes a habit and in some (maybe very important game, you just won’t have time to checkmate). A strong chess player will NEVER waste time, but will deliver a checkmate in the fastest possible way.

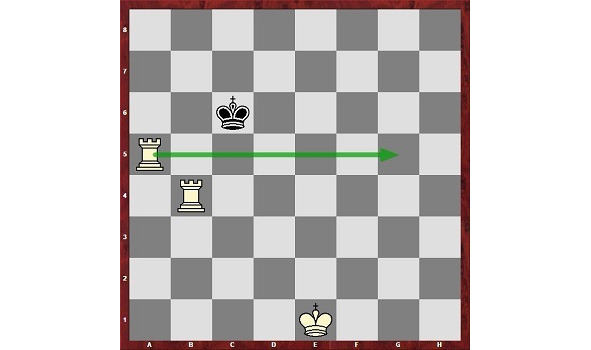

So, once we have determined which side of the board to drive the enemy king to, we begin to give checkmate with the queen and rook in turn.

Example:

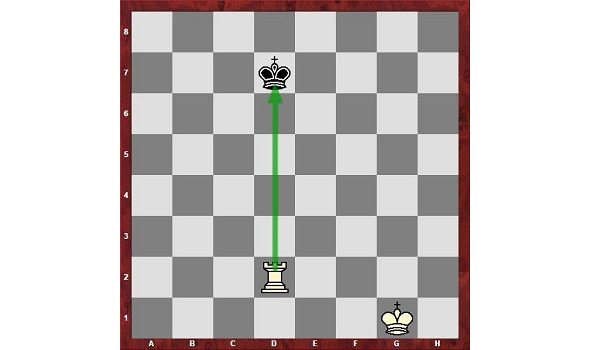

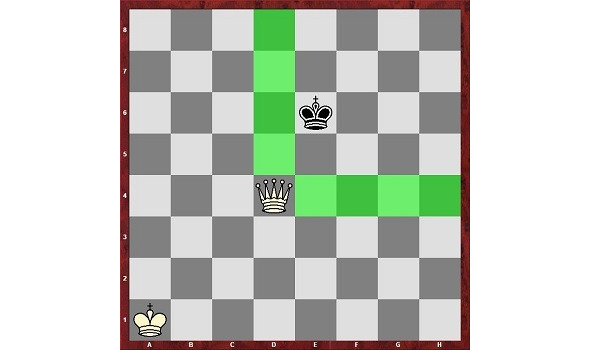

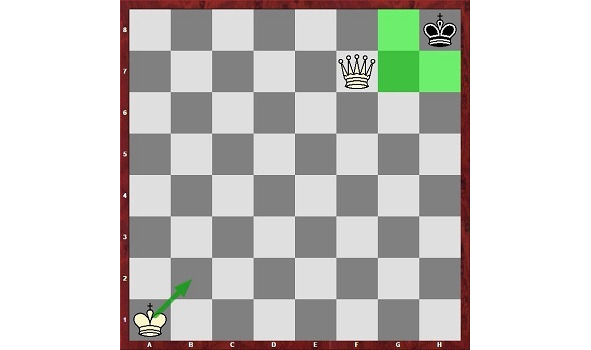

Here is the position to aim for in order to deliver a checkmate with the queen and rook:

The queen (or rook) brings the king to the edge of the board, and the rook (or queen) they checkmate.

Let’s assume that the initial position of the pieces on the board is as follows:

then the king can be brought to the edge of the board in the following way:

1.Qa5+ Kd6 2.Rb6+ Kc7 3.Qa7+ Kc8 4.Rb8#

Remember the technique and try to checkmate. Try moving the black king, white queen, and rook to different positions until you start to be able to bring the king to the edge of the board from any position of the pieces.

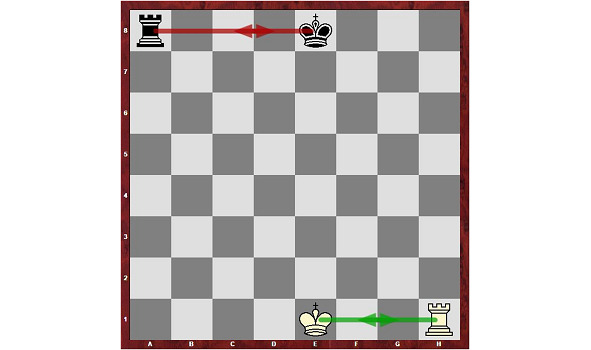

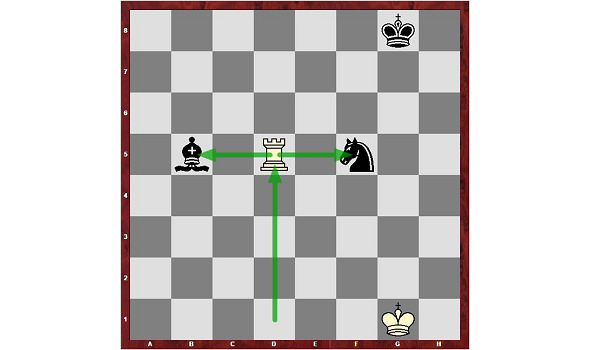

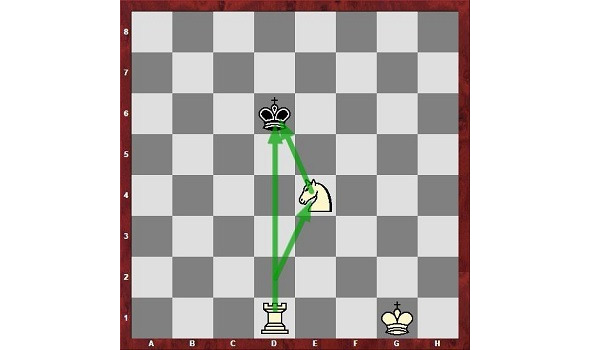

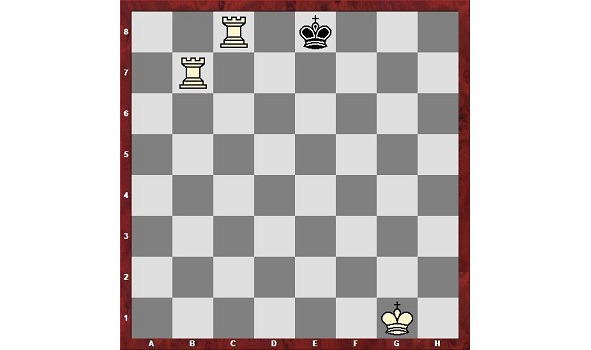

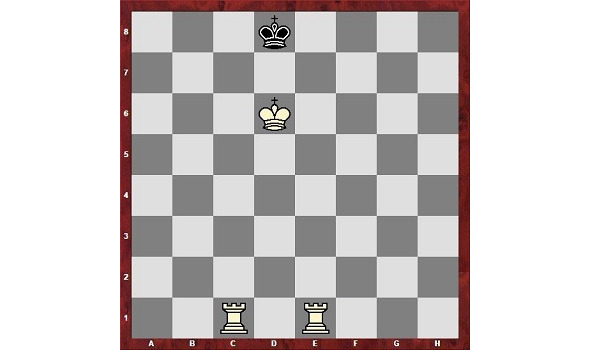

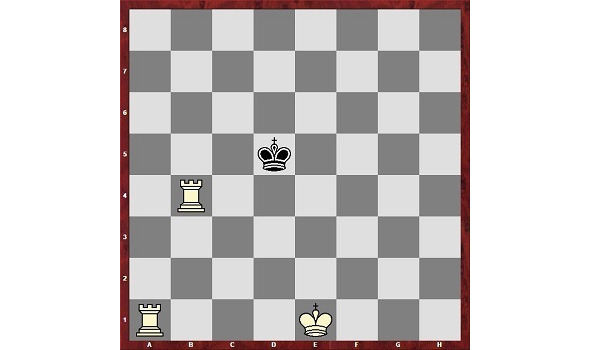

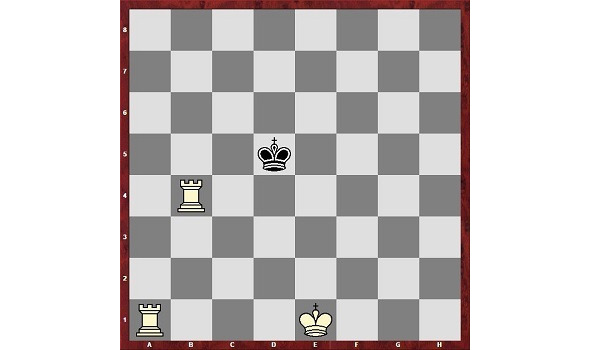

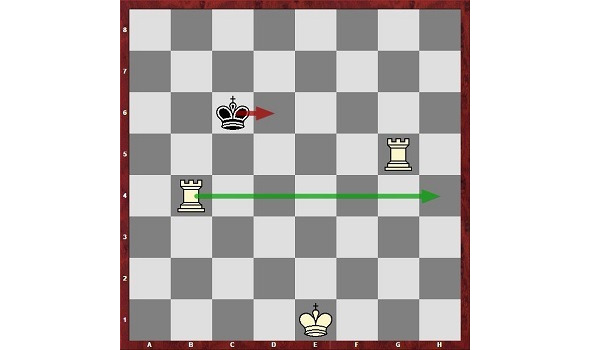

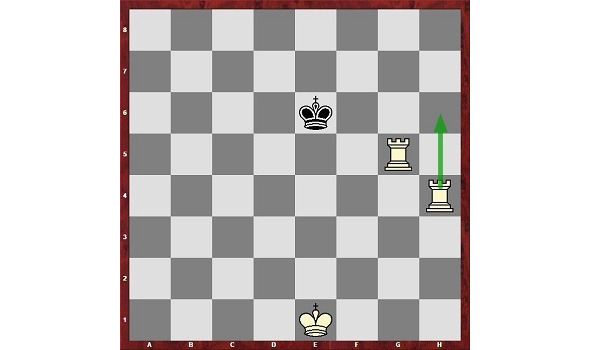

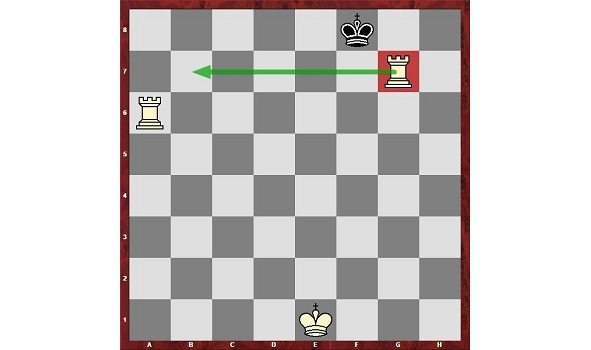

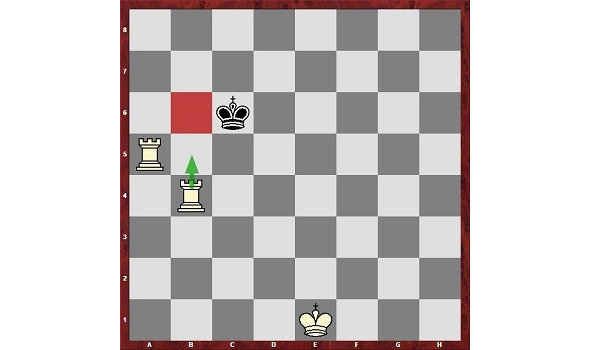

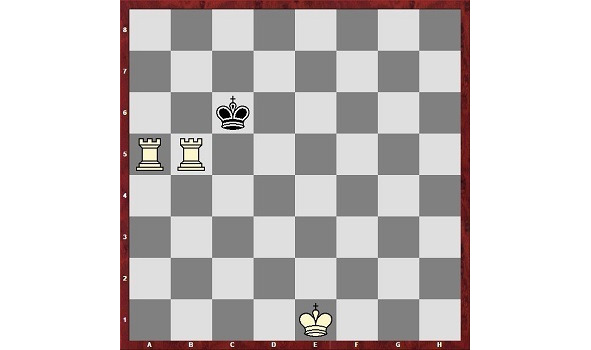

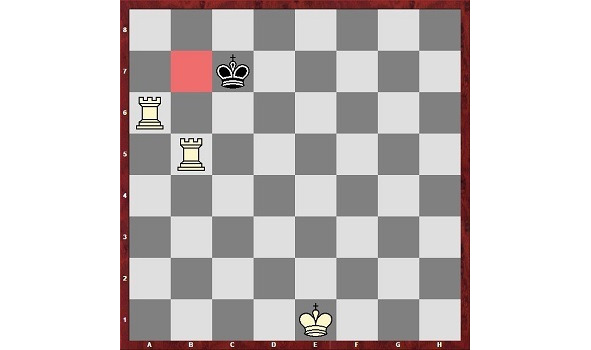

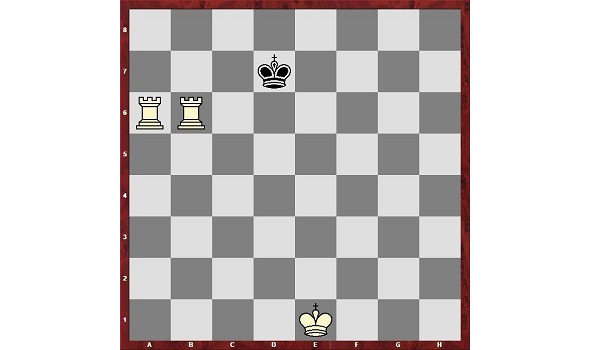

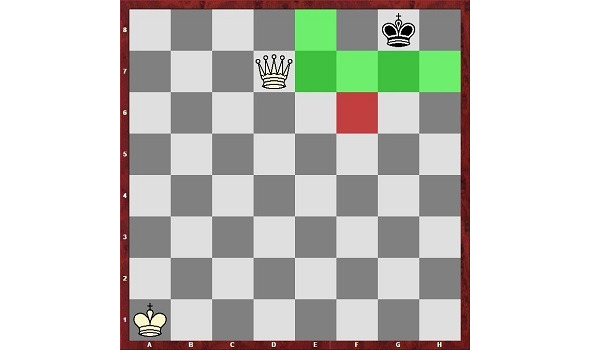

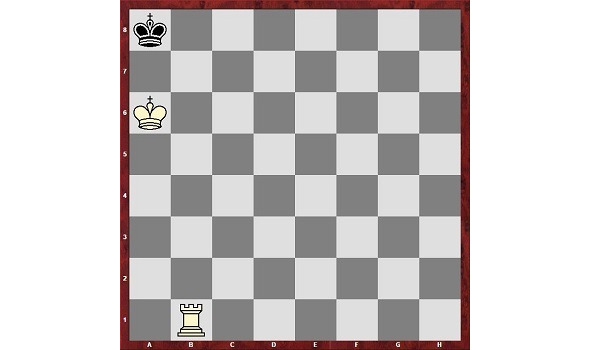

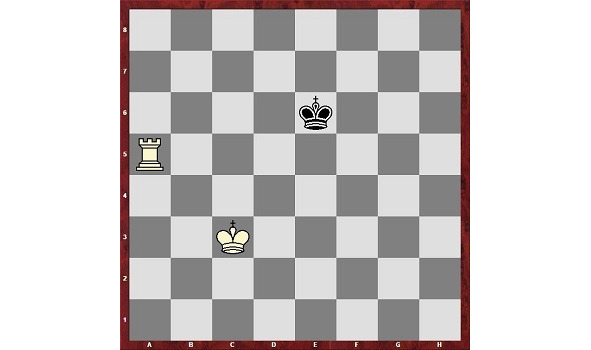

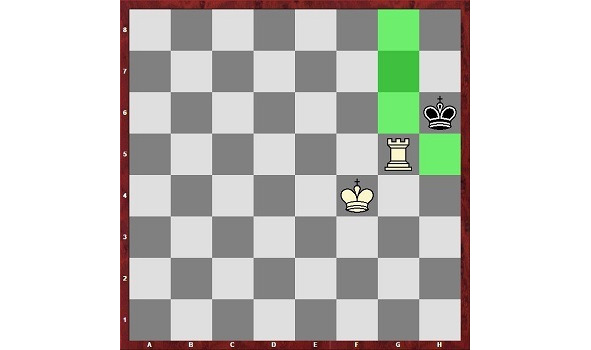

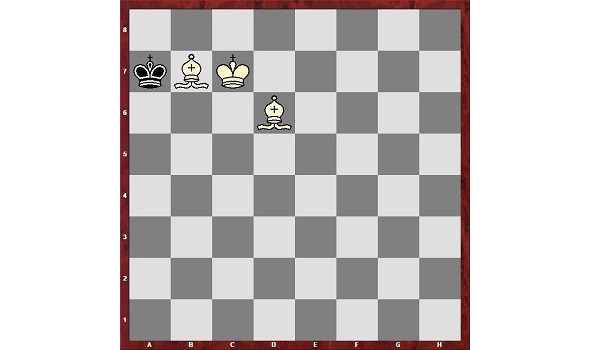

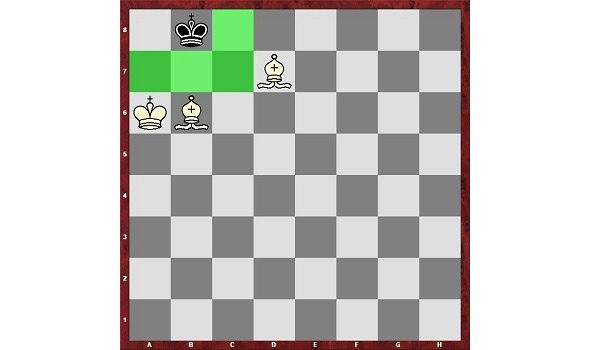

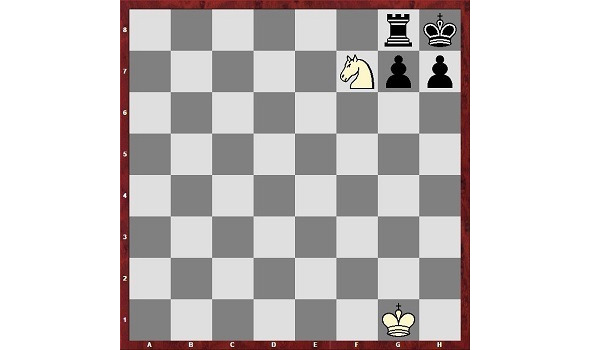

Checkmate with two rooks

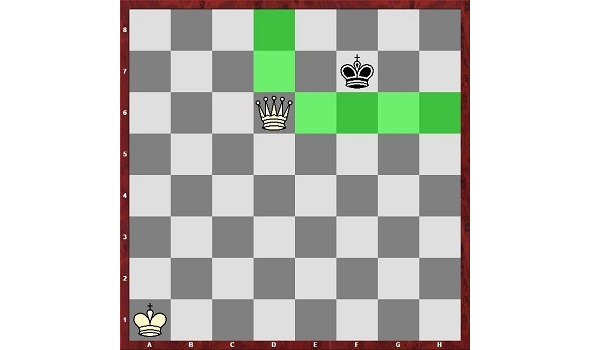

Checkmate with two rooks is slightly different from checkmate with a queen and a rook.

The difference is that when a queen and a rook checkmate, the queen protects the rook all the time, while when two rooks checkmate, they do not protect each other.

Example:

1.Ra5+ Kc6 and it is no longer possible to play 2.Rb6+ as in the case of the queen, because the rook on b6 will be unprotected.

Next, there are two ways to put a linear checkmate:

The first one is easier to remember, but a little longer.,

the second one is shorter.

You may ask why there are two ways, it would be logical to have one that is short?

Let me explain: after that we will consider both examples.

Method 1.