Бесплатный фрагмент - Английский для военных/Military English. Метод кейсов/Cases

Решения, ответы, словарь, глоссарий

ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ

Для преподавателей английского языка или самостоятельной работы студентов.

Уровень английского B2.

Метод кейсов. Метод конкретных ситуаций — техника обучения, использующая описание реальных ситуаций. Обучающиеся должны исследовать ситуацию, разобраться в сути проблем, предложить возможные решения и выбрать лучшие из них.

Военный английский — это изучение и практика английского языка в контексте армии 21 века. Аутентичные материалы представляют реальные источники. В конце каждой темы есть раздел «Ключевые понятия и словарь», чтобы каждый учащийся мог ознакомиться с конкретной военной терминологией и информацией. В каждом кейсе есть все, что вам нужно. Решения, ответ, ключ. Кейсы организованы в четыре группы. Каждый из них может быть прочитан, обсуждён и использован для одной главной цели; и каждый может быть прочитан, обсуждён, и использован, чтобы понять сложность и поведение человека в различных ситуациях. Кейсы помогают преобразовать информацию и примеры в тексте в реальные знания. Предоставлены все ресурсы.

The cases in this book all deal with specific situations, specific problems, specific decisions.

They are all military situations, military problems, and military decisions.

They should thus be approached by students and instructors as cases that ask,

How should one handle this?

What is Military English?

Military English is the study and practice of the English language in the context of the

Military. The authentic materials were selected from real sources being re-written with a more appropriate level of grammar and vocabulary.

At the end of each unit, there is a vocabulary section

so as each student could review the specific military terminology and the information.

All cases have everything you need. Solutions, Answer Key.

.

Как пользоваться данной книгой.

Кейс (от англ. сase) — это описание конкретной ситуации или случая в какой-либо сфере: социальной, экономической, медицинской и т. д. Как правило, кейс содержит не просто описание, но и некую проблему или противоречие и строится на реальных фактах.

Соответственно, решить кейс — это значит проанализировать предложенную ситуацию и найти оптимальное решение.

Кейс-метод позволяет совершенствовать «мягкие навыки» (soft skills),которые оказываются крайне необходимы в реальном рабочем процессе.

Сейчас решение кейсов как метод обучения используется во всех ведущих бизнес-школах, университетах и корпорациях.

Решение кейсов состоит из нескольких шагов:

1) исследования предложенной ситуации (кейса);

2) сбора и анализа недостающей информации;

3) обсуждения возможных вариантов решения проблемы;

4) выработки наилучшего решения.

Как пишутся кейсы

Кейс объединяет в себе два компонента: исследовательский и учебный, поэтому процесс его создания предполагает работу консультанта (я как технический специалист), сертификаты :

— NATO CIMIC AWARENESS COURSE. Информационная подготовка. Civil-Military Cooperation Centre of Excellence (CCOE). Центр подготовки НАТО

— Основы контроля оружия. Химическое, биологическое, ядерное оружие тип1, ядерное оружие тип 2.EU Non-Proliferation Consortium. Консорциум Еевропейского Союза

и преподавателя одновременно (Международные квалификации TESOL, TEFL (право преподавать английский как иностранный в любой стране мира, следуя при этом современной коммуникативной методике).

Задача коммуникативной методики — научить спонтанной речи на любые темы, и перестать переводить мысли с русского на иностранный язык. Коммуникативный подход, в общем и целом, предполагает изучение слов в контексте, без перевода на русский язык. И задача преподавателя не только научить Вас понимать, ЧТО означает слово, но и КАК его употреблять.

PART 1

MILITARY LEADERSHIP STYLE

CASE NUMBER 1

State Loses Control Over Its Nuclear Weapons Illustrative Scenario:

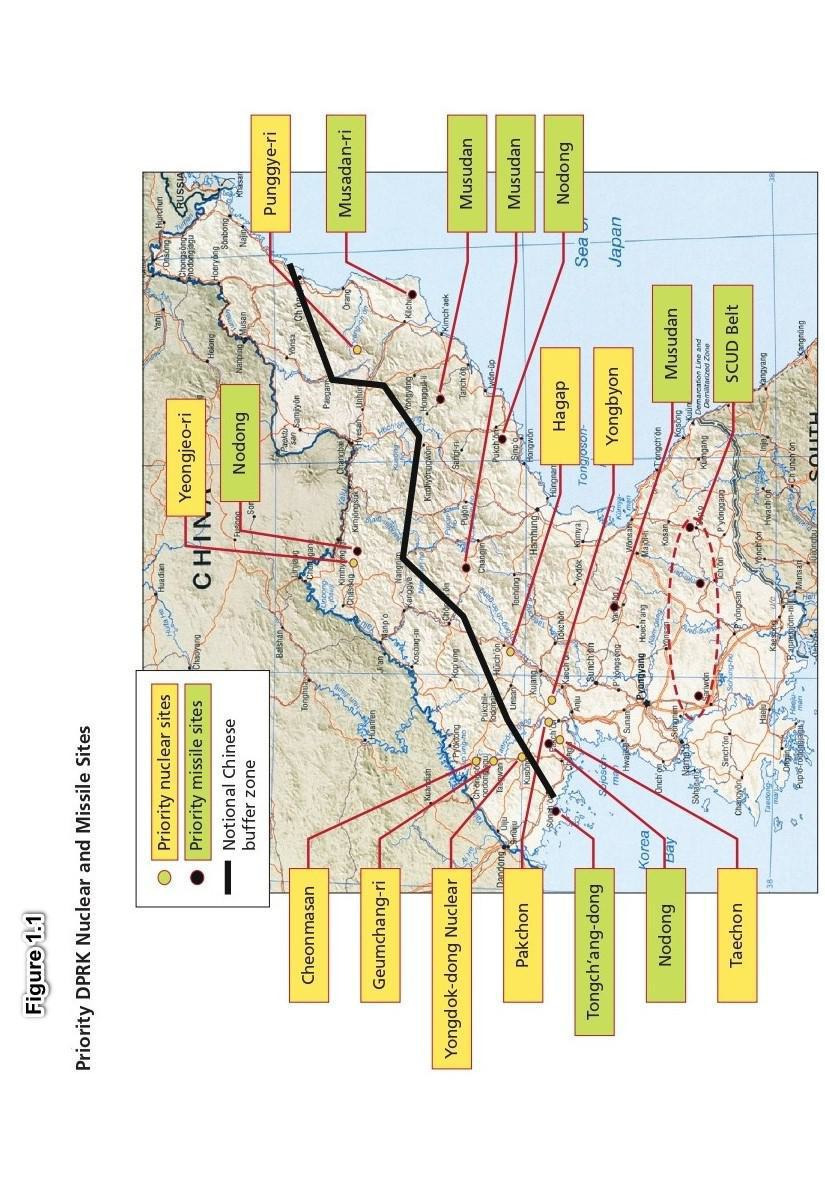

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) DPRK Nuclear, Chemical, Biological, and Missile Sites

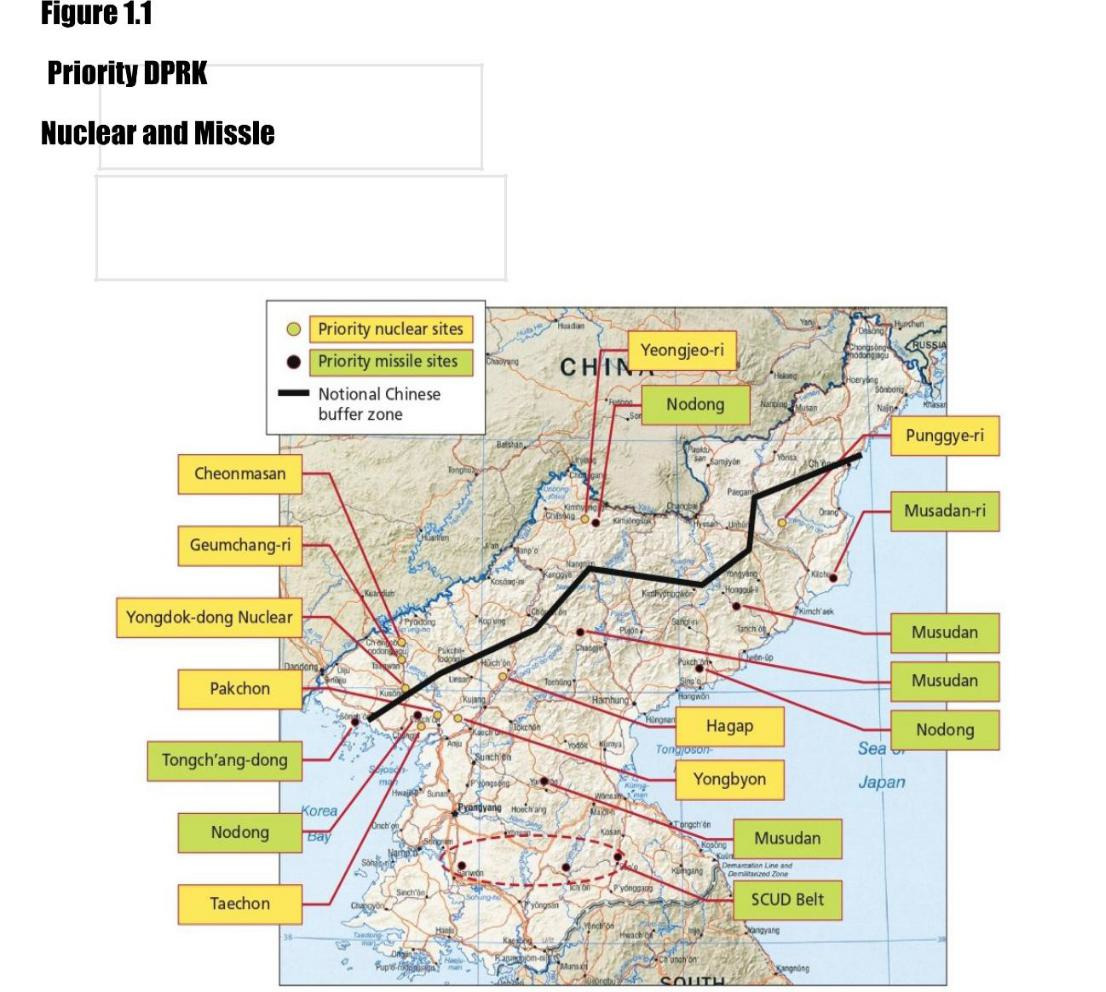

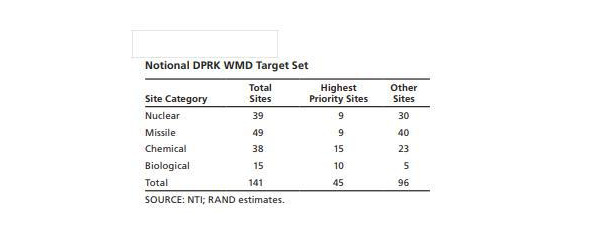

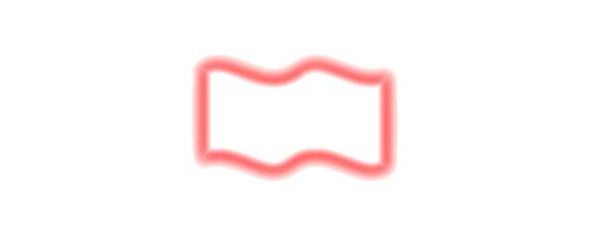

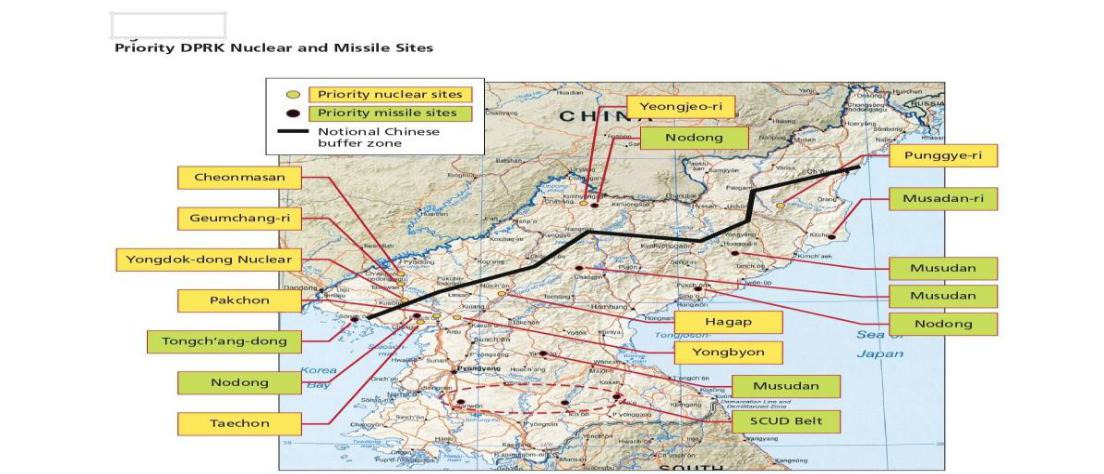

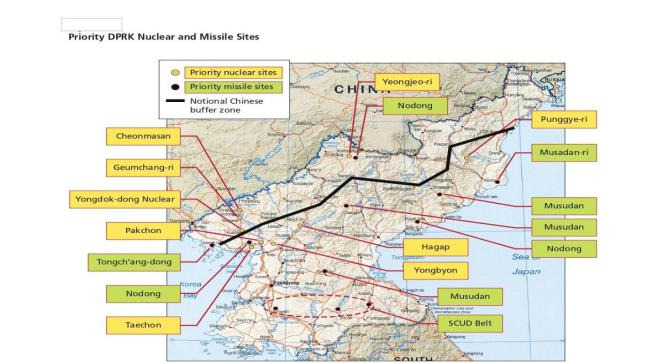

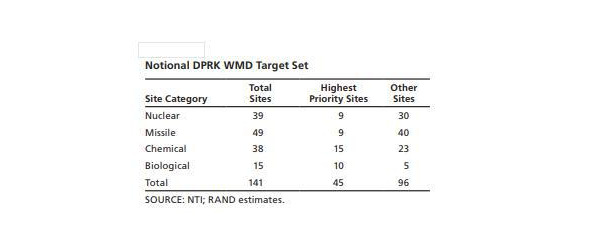

The DPRK’s WMD and missile programs include approximately 141 sites (excluding tactical sites) identified as being of potential interest for WMD-E operations, 39 of which are associated with its nuclear program, 38 are related to its CW program, and 15 are related to its bioweapons (BW) program. An additional 49 sites are associated with the ballistic missiles that might launch WMD.

For WMD-E operations, we assess that the order of priority of these sites would be:

— Nuclear fuel enriching and processing sites, and nuclear weapon manufacturing, testing, and storage sites

— Missile garrisons holding missiles capable of carrying nuclear weapons

— Research and development sites and nuclear-related universities

— Other nuclear sites — including mines, low-grade ore processing

— Biological weapons research and development, manufacturing, testing, and storage sites

— CW research and development, manufacturing, testing, and storage sites.

Unclassified sources identify nine sites in the DPRK that fall into the first category: Yongbyon Nuclear Research Center, one nuclear test site, four additional undeclared nuclear enrichment sites, one suspected underground nuclear storage site, one undeclared underground enrichment and reprocessing site, and one site associated with nuclear weaponization. These nine nuclear sites are shown in Figure 1.1.

The figure also depicts a notional buffer line that might be established by Chinese forces—50 km in this example — in the event that China decides to establish a zone within North Korea to control the flow of refugees or otherwise manage further developments on the peninsula. An interesting feature of such a zone would be the number of priority WMD and missile sites remaining outside it. In this notional case, five nuclear and seven missile sites would remain on the U.S. side.

A key operational decision — and one that will be greatly affected by the quality of available intelligence — will be whether and in what priority to seize and reduce each site. The combined commander/JFC would then develop a campaign plan to exploit these and any other sites found during the course of operations.

Table 1.1

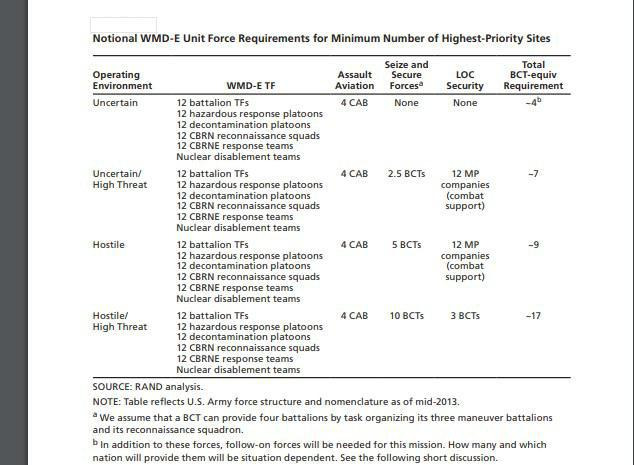

Table 1.2

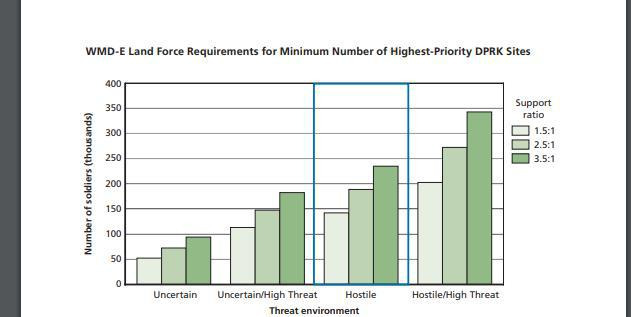

Table 1.3

Questions

— Campaign Design

A WMD-E campaign would balance key objectives and missions; strategic, operational, and tactical risks; and the joint forces needed to interdict, attack, and/or eliminate nuclear forces and sites quickly enough to minimize the risks of proliferation or use. The WMD-E maneuver scheme could adopt one or a combination of the following approaches:

— a northward movement of U.S. ground forces and RoK allies across the DMZ along one or more axes of advance; (2) the introduction of forces from the sea on one or both coasts to reduce the distances that ground forces need to advance to reach priority nuclear WMD sites; and/or (3) air maneuver operations involving airborne or air assault forces directly assaulting the highest-priority sites, with other ground forces maneuvering to meet up with these forces, and joint SOF, air, and naval forces supporting.

— Intelligence Requirements.

The quality and reliability of U.S. intelligence will be critical in winnowing the number of sites to be initially assaulted, seized, and secured down to those that will best reduce the risk of WMD being leaked or employed.

For example, poor intelligence can result in forces being sent to seize and secure sites bereft of WMD

Very good intelligence could, in theory, reduce the number of sites requiring coverage, support the efficient allocation of limited resources, and reduce risk. (In practice, however, North Korean efforts to hide weapons and disguise sites may significantly diminish the effectiveness of U.S. and allied intelligence.)

Two intelligence issues complicate planning for the WMD-E mission.

— First, intelligence gaps will likely mean that critical facilities rumored or reported to exist cannot be located.

— Second, as previously noted, many weapons — particularly CWs — are likely to have been dispersed to numerous tactical operational sites that cannot be identified in advance and are not included in estimates of a country’s WMD infrastructure.

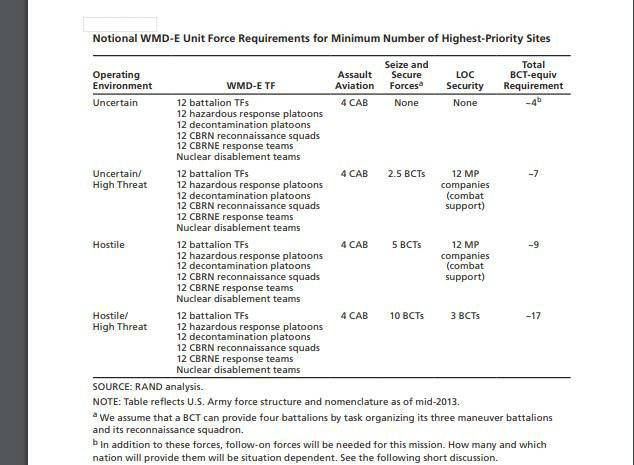

3. Parametric Analyses of WMD-E Force Requirements

We estimated WMD-E forces under different scenario assumptions that varied the following parameters:

1 • the number and sizes of WMD sites for WMD-E operations

2• force requirements dictated by the operational environment

3• the ratio of supporting forces to mission forces.

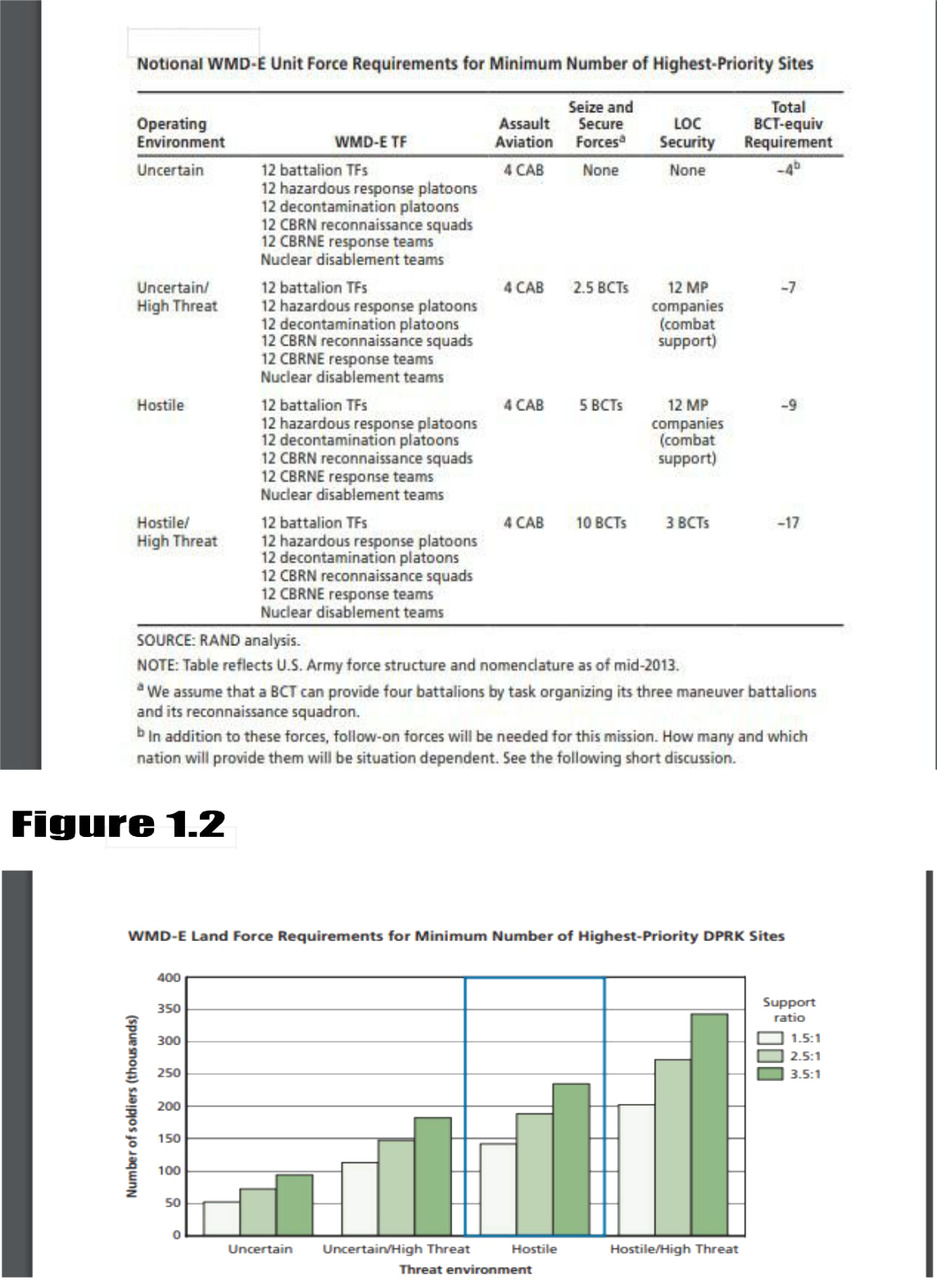

— Sensitivity of Force Requirements to Operational Environments and Support Ratios The ground force requirements are presented as a function of the operating environment (Uncertain or Hostile, and level of threat) and the assumed support ratio (low, midlevel, or high), broken out by the different elements of the WMD-E mission force.

Ground force requirements for WMD-E operations in our illustrative DPRK case are presented in Figure 1.2.

Estimated forces needed for WMD-E operations could be…

5. Observations on the DPRK Case Study

As described in this case study, WMD-E operations in the wake ofa collapse ofthe DPRK.

— What are the assumptions driving results?

— What does Your results suggest?

Welcome To The DPRK (Video)

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1YRUncnqAJ7YDe_N8UeRdpGOwFQZq KDwy/view? usp=sh aring

Solutions

Question 1

1. Campaign Design

A WMD-E campaign would balance key objectives and missions; strategic, operational, and tactical risks; and the joint forces needed to interdict, attack, and/or eliminate nuclear forces and sites quickly enough to minimize the risks of proliferation or use.

The WMD-E maneuver scheme could adopt one or a combination of the following approaches:

— a northward movement of U.S. ground forces and RoK allies across the DMZ along one or more axes of advance; (2) the introduction of forces from the sea on one or both coasts to reduce the distances that ground forces need to advance to reach priority nuclear WMD sites; and/or (3) air maneuver operations involving airborne or air assault forces directly assaulting the highest-priority sites, with other ground forces maneuvering to meet up with these forces, and joint SOF, air, and naval forces supporting.

Answer

Each of the three approaches listed above involves associated benefits and risks.

For example, a northward advance would establish secure areas for elimination operations but could also be quite slow, and such an advance could well face the greatest concentration of opposing DPRK forces — hence, the highest casualties, especially if those DPRK forces had the ability and will to fight.

The approach based on operationally maneuvering from the sea could also face stiff opposition, and it would introduce some logistical challenges, but it would also shorten the distances — and potentially the time — that maneuver and WMD-E TFs have to advance to key DPRK nuclear and missile sites in the north.

Finally,

Figure 1.1

might be the fastest way to seize DPRK nuclear sites until the WMD-E TFs arrive, but this approach could leave the assault forces exposed and isolated. Trade-offs between risks and timelines also exist:

Some risks might be mitigated, for example, by conducting heliborne assault opera-tions against a site only when heavier ground maneuver forces are closing on that site so that assaulting forces can be quickly reinforced.

Question 2

2. Intelligence Requirements.

The quality and reliability of U.S. intelligence will be critical in winnowing the number of sites to be initially assaulted, seized, and secured down to those that will best reduce the risk of WMD being leaked or employed.

For example, poorintelligence can result in forces being sent to seize and secure sites bereft of WMD

Very good intelligence could, in theory, reduce the number of sites requiring coverage, support the efficient allocation of limited resources, and reduce risk. (In practice, however, North Korean efforts to hide weapons and disguise sites may significantly diminish the effectiveness of U.S. and allied intelligence.)

Twointelligence issues complicate planning for the WMD-E mission.

— First, intelligence gaps will likely mean that critical facilities rumored or reported to exist cannot be located.

— Second, as previously noted, many weapons — particularly CWs — are likely to have been dispersed tonumerous tacticaloperationalsites that cannot be identified in advance and are not included in estimates of a country’s WMD infrastructure.

Answer

For the WMD-E mission in North Korea, even in a DPRK collapse scenario, forces searching for WMD will not know what type of resistance they might encounter. TFs should consist, therefore, of both WMD specialists and general-purpose forces that are adequate for the potential threat and tactical situation. This could be a significant consideration given the nature of North Korea’s armed forces and the degree to which its population is armed and indoctrinated to fear and distrust U.S. and RoK forces.

Figure 1.1

Question 3

3. Parametric Analyses of WMD-E Force Requirements

We estimated WMD-E forces under different scenario assumptions that varied the following parameters:

1 • the number and sizes of WMD sites for WMD-E operations

2• force requirements dictated by the operational environment

3• the ratio of supporting forces to mission forces.

Answer

1.The number and sizes of WMD sites for WMD-E operations.

For WMD- E operations, we assess that the nuclear sites associated with fuel enriching and processing would be the next priorities, along with nuclear weapon manufacturing, testing, and storage sites. For our base case, we selected 12 battalion TFs as the minimum force that a commander should be allocated to seize, secure, search, and eliminate the priority nuclear sites. We note that 12 WMD-E TFs is a planning factor only.

For example, if intelligence suggests that the highest-priority nuclear activities should be conducted at nine sites, as shown in Table 1.1,

Table 1.1

then a minimum of ten battalion-sized TFs should be assigned to these nine sites. In the course of an operation, the U.S. commander might use these 12 WMD-E TFs

differently. For example, recall that in Figure 4.1 four of the priority nuclear sites and two of

the priority missile sites were located approximately 50 km from the Chinese border.

2. Operational environment and force requirements.

— WMD-E (Uncertain): This environment features a low threat level — consistent with the collapse of the DPRK regime and complete disintegration of the military. This might occur if a power struggle within the Kim regime resulted in open fighting that pushes an already dangerously unstable economy and society into chaos and collapse.

— WMD-E (Uncertain/High Threat)

This environment features a greater threat level — consistent with the collapse of the DPRK regime and the higher echelons of its military. As in the Uncertain case above, this environment might arise from a violent conflict within the DPRK’s leadership.

— WMD-E (Hostile):the basis of the Hostile environment is that U.S. entry into North Korea would be met with hostility by former regime and military members and perhaps many in the general public. In the internal collapse case, entering North Korea might be predicated on relieving a massive humanitarian catastrophe and controlling refugee flows — with securing WMD being necessary to prevent their transfer.

— WMD-E (Hostile/High Threat): This environment features the collapse of the DPRK regime but with the military remaining intact to a large extent. This environment might result from an internal regime struggle and collapse as before. But, in this case, the military manages to hold itself together.

We used these four environment descriptions to calculate the forces required for the missions shown in Table 1.2.

In each case, we assessed that a battalion-sized WMD-E TF was the minimum size needed to provide sufficient organic security at each site and that — at a minimum—12 such TFs would be provided (ten for priority nuclear sites, with two in reserve for pop-up targets).

3. Ratio of supporting forces to mission forces.

For operations in the DPRK, such support would most likely be provided by military units:

— 1.5:1: This represents the lower-end bound of OIF and OEF support for Army operations.

— 2.5:1: We use this ratio for our baseline. It represents the midlevel support ratios experienced in OIF and OEF.

— 3.5:1: This represents the high-end bound of OIF and OEF support.

We chose the 2.5:1 support ratio for our baseline estimate to support WMD-E operations in the DPRK, and show the parametric variants of ratios higher or lower than this number.

Question 4

— Sensitivity of Force Requirements to Operational Environments and Support Ratios

The ground force requirements are presented as a function of the operating environment (Uncertain or Hostile, and level of threat) and the assumed support ratio (low, midlevel, or high), broken out by the different elements of the WMD-E mission force.

Ground force requirements for WMD-E operations in our illustrative DPRK case are presented in Figure 1.2.

Estimated forces needed for WMD-E operations could be…

Answer

Figure 1.2

Example:• 73,000 troops for an Uncertain environment — with a lower bound of 52,000 if significant contractor logistics support can be employed and an upper bound of 94,000 if all support must be provided by the U.S. military • 148,000 for an Uncertain/High Threat environment — with a lower bound of 113,000 with more contractor logistics support and an upper bound of 182,000 with all U.S. military support.

Since we think that the environment is likely to be Hostile and that the intermediate level of support will be needed in the DPRK, our best estimate is a requirement for 188,000 U.S. ground troops.

That estimate could decrease to 148,000 if the risk of attack from DPRK military remnants decreases.

It could increase to 273,000 if the environment worsens to become High Threat. It is also useful to recall that these estimates are for the WMD-E mission only — they do not include force requirements for other missions, such as humanitarian assistance.

These different security levels pertain to the disposition of the DPRK security forces and any insurgent forces that might rise up.

Question 5

5. Observations on the DPRK Case Study

As described in this case study, WMD-E operations in the wake of a collapse of the DPRK.

1.What are the assumptions driving results?

— What does Your results suggest?

Answer

The WMD-E requirement is a nontraditional mission that creates a need for forces in addition to those required for joint operations, the force requirements of which might already be quite large.

The key assumptions driving results are the following:

— • the number and sizes of the WMD sites that are to be searched, the time needed to clear each site, and the priority and urgency of clearing them

— • the degree to which non-U.S. forces could or would be relied upon to service nuclear and nonnuclear sites

— • the ratio of support to mission troops

— • the degree of hostility in the operational environment, as well as the military threats WMD-E forces may face.

Our results suggest that even in cases where relatively favorable assumptions are made, the estimated U.S. forces required can still be quite substantial:

For example, in our DPRK base case, our estimate for the Uncertain environment — a relatively favorable environment for conducting WMD-E operations — required an estimated 73,000 troops,

while a more hostile operating environment or more expansive

missions required significantly more troops.

Actual WMD-E operations are likely to be far more challenging.

You can read the full version

CASE 2

Practical Speaking Training. Сrush the fear of public speaking

1. DRAW A CARTOON (Naval Admiral William McRaven`s addresses.)

What 1 lesson from this speech can you apply to your own life?

Directions:

Use the narrator’s descriptions to help you draw three Scenes and the characters.

— After you draw each scene, write what the characters talked or thought about.

— If the characters talk to each other, write their conversation in a speech bubble.

— Write a character’s thoughts about anything in a thought bubble.

Example: «If you want to change the world get over being a sugar cookie and keep moving forward.»

«There were many a student who just couldn’t accept the fact that all their effort was in vain… Those students didn’ t under-stand the purpose of the drill. You were never going to suc-ceed. You were never going to have a perfect uniform.»

As you brainstorm the story`s characters, think about which are their main

motivations. Which are their secondary ones?

Create your Speech.

The goal of this presentation is to show you how a speech success isn’t the re-sult of good luck, ability.

The speech success is simply a case of taking the steps required to introduce changes and bring revolution in every field, inspiration from your speech. How big your heart is.

Do you agree?

What were some of the main messages of this particular speech?

List the main points and themes.

— Oratory — What words or phrases helped to support the speech’s main pur-poses? In particular, which words or phrases evoked emotion, painted a strong image or are very descriptive. How do the words and phrases you’ve pointed out lend to (or distract from) the points being made?

— Emotion — What emotions do you believe Naval Admiral William McRaven was trying to evoke? Do you believe this was achieved? If so, what words in particular helped to convey emotion?

— Audience — To whom is Naval Admiral William McRaven trying to appeal? What words help you come to this conclusion?

— Delivery — What do you notice about Naval Admiral William McRaven `s use of elements like tone of voice, inflection, pause, pacing, rising and falling volume and body language to emphasize specific points in the speech?

There are many issues you can talk about at your inauguration. How do you pick one? A good idea is to look inside yourself and find out what you feel very deeply about. Maybe it’s the environment. Or you feel that downloading music on the Internet should be free. Your issue should reflect who you are and what you care about.

DRAW A CARTOON

1. Establish your character by asking each other

«wh’ questions (who, what, when, where, why and how). You should then discuss any points that they think are im-portant to support your point of view.

2 Storyboard Creator makes amazing visuals and graphic

https://www.storyboardthat.com/

— Organizers for digital storytelling.

— The role play can begin.

You have a maximum of three minutes to present your story.

— After the role-play is finished, an issue.

— Making notes will help you to remember the important points.

Example:

Write your speech.

— Keeping it simple

1. Write Like You Talk

Remember that you’re writing a speech, not an essay.

People will hear the speech, not read it.

— Use short sentences. It’s better to write two simple sentences than one long, complicated sentence.

— Use contractions. Say «I’m» instead of «I am» «we’re» in-stead of «we are.»

— Don’t use big words that you wouldn’t use when talk-ing to someone.

— You don’t have to follow all the rules of written English grammar.

«Like this. See? Got it? Hope so.»

— Always read your speech aloud while you’re writing it.

You’ll hear right away if you sound like a book or a real person talking!

— Use Concrete Words and Examples

Concrete details keep people interested. For instance, which is more effective? A vague sentence like «Open play spaces for children’s sports are in short supply.» Or the more concrete «We need more baseball and soccer fields for our kids.»

— Get Your Facts Together

You want people to believe that you know what you’re talking about!

So you’ll need to do some research.

For instance, let’s say your big issue is the environment. You promise to pass a law that says all new cars must run on electricity, not gas. That will cut down on air pollution! But it would help if you had a few facts:

How much bad air does one car create each year? How many new cars are sold in the world every year? So how much will pollution be cut every year?

Use the library or the Internet to do research. Your new policy proposal will sound really strong if you have the facts to back it up.

5. Persuade With a Classic Structure

In a speech where you’re trying to persuade someone, the classic structure is called «Problem-Solution.» In the first part of your speech you say, «Here’s a problem, here’s why things are so terrible.» Then, in the second part of your speech you say, «Here’s what we can do to make things better.» Sometimes it helps to persuade people if you have statistics or other facts in your speech. And sometimes you can persuade people by quoting some-one else that the audience likes and respects.

6. Simplify

After you’ve written a first draft of your speech, go back and look for words you can cut.

«Fewer Words = Clearer Point.» It helps her remember to always simplify a speech by cutting out words.

Exam

People make decisions based on what they see and hear.

Body language — make sure that you have a proper posture. If your shoulders are sagging and your legs are crossed, you will not appear as being sincere and people just will not ac-cept your message.

— Clothing. Talk about an outfit that inspires confidence, trust and strength.

— Articulation — articulation means how their total vocal process works.

— Pronunciation — you need to pronounce each word.

— Pitch — pitch refers to the highs and lows of the voice.

— Speed — the speed, or pace, is an important variable

to control. Between 140—160 words per minute is the nor-mal pace for a persuasive speech.

— Pauses — the pause, or caesura, is a critical persuasive tool. When they want to emphasize a certain word, have them just pause for one second before; this highlights the word.

— Volume — volume is another good tool for a persua-sive speech.

— Quality — quality of voice is gauged by the overall impact that their voice has on their listeners.

— Use of notes.

— Know 100 Words For Every Word That You Speak.

— Record Yourself And Learn Your Voice

Record your speech on your phone or video camera. end.

— Then listen to it or watch it, and make notes on how you could make it better. Some people do not like listen-ing to the sound of their voice on tape, so it is important that you get used to your own voice and speaking style.

— Try to eliminate all of your fears of rejection. The audience is there to listen to you for a reason.

Focus On The Material, Not The Audience.. Re-member that there will always be people who are bored or tired. None of these audience reac-tions have anything to do with you personally.

— Your strongest critic is you. When you finish a speech or delivering a presentation, give yourself a pat on the back.

— You overcame your fears and you did it.

Have pride in yourself.

In 2014, Naval Admiral William McRaven gave one of the most motivational and inspiring commencement addresses. Filled with personal experiences and timeless advice, and after 37 years of military service, I consider this advice worth taking. Admiral McRaven lays out the 10 life lessons from his experience as a Navy SEAL that can be applied to all areas of our life.

Speech Transcript

President Powers, Provost Fenves, Deans, members of the faculty, family and friends and most importantly, the class of 2014. Congratulations on your achieve-ment.

It’s been almost 37 years to the day that I graduated from UT. I remember a lot of things about that day. I remember I had throbbing headache from a party the night before. I remember I had a serious girlfriend, whom I later married — that’s important to remember by the way — and I remember that I was getting commissioned in the Navy that day.

But of all the things I remember, I don’t have a clue who the commencement speaker was that evening, and I certainly don’t remember anything they said. So, acknowledg-ing that fact, if I can’t make this commencement speech memorable, I will at least try to make it short.

The University’s slogan is, «What starts here changes the world.» I have to admit — I kinda like it. «What starts here changes the world.»

Tonight there are almost 8,000 students graduating from UT. That great paragon of analytical rigor, Ask.Com, says that the average American will meet 10,000 people in their lifetime. That’s a lot of folks. But, if every one of you changed the lives of just 10 people — and each one of those folks changed the lives of another 10 people — just 10 — then in five generations — 125 years — the class of 2014 will have changed the lives of 800 million people.

800 million people — think of it — over twice the population of the United States. Go one more generation and you can change the entire population of the world — eight billion people.

If you think it’s hard to change the lives of 10 people — change their lives forever — you’re wrong. I saw it happen every day in Iraq and Afghanistan: A young Army offi-cer makes a decision to go left instead of right down a road in Baghdad and the 10 soldiers in his squad are saved from close-in ambush. In Kandahar province, Afgha-nistan, a non-commissioned officer from the Female Engagement Team senses something isn’t right and directs the infantry platoon away from a 500-pound IED, saving the lives of a dozen soldiers.

But, if you think about it, not only were these soldiers saved by the decisions of one person, but their children yet unborn were also saved. And their children’s children were saved. Generations were saved by one decision, by one person.

But changing the world can happen anywhere and anyone can do it. So, what starts here can indeed change the world, but the question is — what will the world look like after you change it?

Well, I am confident that it will look much, much better. But if you will humor this old sailor for just a moment, I have a few suggestions that may help you on your way to a better a world. And while these lessons were learned during my time in the military, I can assure you that it matters not whether you ever served a day in uniform. It mat-ters not your gender, your ethnic or religious background, your orientation or your so-cial status.

Our struggles in this world are similar, and the lessons to overcome those struggles and to move forward — changing ourselves and the world around us — will apply equally to all.

I have been a Navy SEAL for 36 years. But it all began when I left UT for Basic SEAL training in Coronado, California. Basic SEAL training is six months of long torturous runs in the soft sand, midnight swims in the cold water off San Diego, obstacles courses, unending calisthenics, days without sleep and always being cold, wet and miserable. It is six months of being constantly harrassed by professionally trained warriors who seek to find the weak of mind and body and eliminate them from ever becoming a Navy SEAL.

But, the training also seeks to find those students who can lead in an environment of constant stress, chaos, failure and hardships. To me basic SEAL training was a life-time of challenges crammed into six months.

So, here are the 10 lessons I learned from basic SEAL training that hopefully will be of value to you as you move forward in life.

Every morning in basic SEAL training, my instructors, who at the time were all Viet-nam veterans, would show up in my barracks room and the first thing they would in-spect was your bed. If you did it right, the corners would be square, the covers pulled tight, the pillow centered just under the headboard and the extra blanket folded neatly at the foot of the rack — that’s Navy talk for bed.

It was a simple task — mundane at best. But every morning we were required to make our bed to perfection. It seemed a little ridiculous at the time, particularly in light of the fact that were aspiring to be real warriors, tough battle-hardened SEALs, but the wisdom of this simple act has been proven to me many times over.

If you make your bed every morning you will have accomplished the first task of the day. It will give you a small sense of pride, and it will encourage you to do another task and another and another. By the end of the day, that one task completed will have turned into many tasks completed. Making your bed will also reinforce the fact that little things in life matter. If you can’t do the little things right, you will never do the big things right.

And, if by chance you have a miserable day, you will come home to a bed that is made — that you made — and a made bed gives you encouragement that tomorrow will be better.

If you want to change the world, start off by making your bed.

During SEAL training the students are broken down into boat crews. Each crew is seven students — three on each side of a small rubber boat and one coxswain to help guide the dingy. Every day your boat crew forms up on the beach and is instruct-ed to get through the surfzone and paddle several miles down the coast. In the win-ter, the surf off San Diego can get to be 8 to 10 feet high and it is exceedingly difficult to paddle through the plunging surf unless everyone digs in. Every paddle must be synchronized to the stroke count of the coxswain. Everyone must exert equal effort or the boat will turn against the wave and be unceremoniously tossed back on the beach.

For the boat to make it to its destination, everyone must paddle. You can’t change the world alone — you will need some help — and to truly get from your starting point to your destination takes friends, colleagues, the good will of strangers and a strong coxswain to guide them.

If you want to change the world, find someone to help you paddle.

Over a few weeks of difficult training my SEAL class, which started with 150 men, was down to just 35. There were now six boat crews of seven men each. I was in the boat with the tall guys, but the best boat crew we had was made up of the the little guys — the munchkin crew we called them — no one was over about five-foot-five.

The munchkin boat crew had one American Indian, one African American, one Polish American, one Greek American, one Italian American, and two tough kids from the midwest. They out-paddled, out-ran and out-swam all the other boat crews. The big men in the other boat crews would always make good-natured fun of the tiny little flip-pers the munchkins put on their tiny little feet prior to every swim. But somehow these little guys, from every corner of the nation and the world, always had the last laugh — swimming faster than everyone and reaching the shore long before the rest of us.

SEAL training was a great equalizer. Nothing mattered but your will to succeed. Not your color, not your ethnic background, not your education and not your social status.

If you want to change the world, measure a person by the size of their heart, not the size of their flippers.

Several times a week, the instructors would line up the class and do a uniform in-spection. It was exceptionally thorough. Your hat had to be perfectly starched, your uniform immaculately pressed and your belt buckle shiny and void of any smudges. But it seemed that no matter how much effort you put into starching your hat, or pressing your uniform or polishing your belt buckle — it just wasn’t good enough. The instructors would find «something» wrong.

For failing the uniform inspection, the student had to run, fully clothed into the surf-zone and then, wet from head to toe, roll around on the beach until every part of your body was covered with sand. The effect was known as a «sugar cookie.» You stayed in that uniform the rest of the day — cold, wet and sandy.

There were many a student who just couldn’t accept the fact that all their effort was in vain. That no matter how hard they tried to get the uniform right, it was unappreciat-ed. Those students didn’t make it through training. Those students didn’t understand the purpose of the drill. You were never going to succeed. You were never going to have a perfect uniform.

Sometimes no matter how well you prepare or how well you perform you still end up as a sugar cookie. It’s just the way life is sometimes.

If you want to change the world get over being a sugar cookie and keep moving for-ward.

Every day during training you were challenged with multiple physical events — long runs, long swims, obstacle courses, hours of calisthenics — something designed to test your mettle. Every event had standards — times you had to meet. If you failed to meet those standards your name was posted on a list, and at the end of the day those on the list were invited to a «circus.» A circus was two hours of additional calis-thenics designed to wear you down, to break your spirit, to force you to quit.

No one wanted a circus.

A circus meant that for that day you didn’t measure up. A circus meant more fatigue

— and more fatigue meant that the following day would be more difficult — and more circuses were likely. But at some time during SEAL training, everyone — everyone — made the circus list.

But an interesting thing happened to those who were constantly on the list. Over time those students — who did two hours of extra calisthenics — got stronger and stron-ger. The pain of the circuses built inner strength, built physical resiliency.

Life is filled with circuses. You will fail. You will likely fail often. It will be painful. It will be discouraging. At times it will test you to your very core.

But if you want to change the world, don’t be afraid of the circuses.

At least twice a week, the trainees were required to run the obstacle course. The ob-stacle course contained 25 obstacles including a 10-foot high wall, a 30-foot cargo net and a barbed wire crawl, to name a few. But the most challenging obstacle was the slide for life. It had a three-level 30-foot tower at one end and a one-level tower at the other. In between was a 200-foot-long rope. You had to climb the three-tiered tower and once at the top, you grabbed the rope, swung underneath the rope and pulled yourself hand over hand until you got to the other end.

The record for the obstacle course had stood for years when my class began training in 1977. The record seemed unbeatable, until one day, a student decided to go down the slide for life head first. Instead of swinging his body underneath the rope and in-ching his way down, he bravely mounted the TOP of the rope and thrust himself for-ward.

It was a dangerous move — seemingly foolish, and fraught with risk. Failure could mean injury and being dropped from the training. Without hesitation the student slid down the rope perilously fast. Instead of several minutes, it only took him half that time and by the end of the course he had broken the record.

If you want to change the world sometimes you have to slide down the obstacle head first.

During the land warfare phase of training, the students are flown out to San Clemente Island which lies off the coast of San Diego. The waters off San Clemente are a breeding ground for the great white sharks. To pass SEAL training there are a series of long swims that must be completed. One is the night swim.

Before the swim the instructors joyfully brief the trainees on all the species of sharks that inhabit the waters off San Clemente. They assure you, however, that no student has ever been eaten by a shark — at least not recently. But, you are also taught that if a shark begins to circle your position — stand your ground. Do not swim away. Do not act afraid. And if the shark, hungry for a midnight snack, darts towards you — then summon up all your strength and punch him in the snout, and he will turn and swim away.

There are a lot of sharks in the world. If you hope to complete the swim you will have to deal with them.

So, if you want to change the world, don’t back down from the sharks.

As Navy SEALs one of our jobs is to conduct underwater attacks against enemy ship-ping. We practiced this technique extensively during basic training. The ship attack mission is where a pair of SEAL divers is dropped off outside an enemy harbor and then swims well over two miles — underwater — using nothing but a depth gauge and a compass to get to their target.

During the entire swim, even well below the surface, there is some light that comes through. It is comforting to know that there is open water above you. But as you ap-proach the ship, which is tied to a pier, the light begins to fade. The steel structure of the ship blocks the moonlight, it blocks the surrounding street lamps, it blocks all am-bient light.

To be successful in your mission, you have to swim under the ship and find the keel

— the centerline and the deepest part of the ship. This is your objective. But the keel is also the darkest part of the ship — where you cannot see your hand in front of your face, where the noise from the ship’s machinery is deafening and where it is easy to get disoriented and fail.

Every SEAL knows that under the keel, at the darkest moment of the mission, is the time when you must be calm, composed — when all your tactical skills, your physical power and all your inner strength must be brought to bear.

If you want to change the world, you must be your very best in the darkest moment.

The ninth week of training is referred to as «Hell Week.» It is six days of no sleep, con-stant physical and mental harassment, and one special day at the Mud Flats. The Mud Flats are area between San Diego and Tijuana where the water runs off and cre-ates the Tijuana slues, a swampy patch of terrain where the mud will engulf you.

It is on Wednesday of Hell Week that you paddle down to the mud flats and spend the next 15 hours trying to survive the freezing cold mud, the howling wind and the in-cessant pressure to quit from the instructors. As the sun began to set that Wednes-day evening, my training class, having committed some «egregious infraction of the rules» was ordered into the mud.

The mud consumed each man till there was nothing visible but our heads. The in-structors told us we could leave the mud if only five men would quit — just five men

— and we could get out of the oppressive cold. Looking around the mud flat it was apparent that some students were about to give up. It was still over eight hours till the sun came up — eight more hours of bone-chilling cold.

The chattering teeth and shivering moans of the trainees were so loud it was hard to hear anything. And then, one voice began to echo through the night, one voice raised in song. The song was terribly out of tune, but sung with great enthusiasm. One voice became two and two became three and before long everyone in the class was sing-ing. We knew that if one man could rise above the misery then others could as well.

The instructors threatened us with more time in the mud if we kept up the singingbut the singing persisted. And somehow the mud seemed a little warmer, the wind a little tamer and the dawn not so far away.

If I have learned anything in my time traveling the world, it is the power of hope. The power of one person — Washington, Lincoln, King, Mandela and even a young girl from Pakistan, Malala — one person can change the world by giving people hope.

So, if you want to change the world, start singing when you’re up to your neck in mud.

Finally, in SEAL training there is a bell. A brass bell that hangs in the center of the compound for all the students to see. All you have to do to quit is ring the bell.

Ring the bell and you no longer have to wake up at 5 o’clock. Ring the bell and you no longer have to do the freezing cold swims. Ring the bell and you no longer have to do the runs, the obstacle course, the PT — and you no longer have to endure the hardships of training. Just ring the bell.

If you want to change the world don’t ever, ever ring the bell.

To the graduating class of 2014, you are moments away from graduating. Moments away from beginning your journey through life. Moments away from starting to change the world — for the better. It will not be easy.

But, YOU are the class of 2014, the class that can affect the lives of 800 million peo-ple in the next century.

Start each day with a task completed. Find someone to help you through life. Re-spect everyone.

Know that life is not fair and that you will fail often. But if take you take some risks, step up when the times are toughest, face down the bullies, lift up the downtrodden and never, ever give up — if you do these things, then the next generation and the generations that follow will live in a world far better than the one we have today.

And what started here will indeed have changed the world — for the better.

Thank you very much. Hook ’em horns.

Practice makes perfect. If there is a video of your speech, watch it and make notes on how you can improveve on it for next

time.

Vocabulary and Terminology Section

1. Action.

What you DO is as important as the BE and KNOW aspects of the Army Leader-ship Philosophy.

— An army leader

An army leader is anyone who by virtue of assumed role or assigned responsibility inspires and influences people to accomplish organizational goals.

BE-KNOW-DO

The army uses the shorthand expression of BE-KNOW-DO to concentrate on key factors of leadership, KNOW, DO represents specified elements of character, knowledge and behavior

4.Character

It is how you demonstrate the values you uphold. Who you are is not something that can be turned on and off.

— Competence

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.