Бесплатный фрагмент - Ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans

Introduction

In the modern world, the urgency of the problems of the ethnic history of the peoples of various regions of our planet is obvious. The growth of ethnic self-awareness, which has been observed everywhere in recent decades, is accompanied by an increase in interest in the historical past of peoples, in the transformations that each of them experienced in the course of its millennia-old formation. It became a spiritual need for a representative of a modern urbanized society to find the roots of his ethnic existence, to understand the diverse processes that led to the formation of that ethnocultural environment through which he perceives the world around him.

Since the origin and historical existence of the overwhelming majority of the peoples of our planet was associated with numerous migrations, movements to new habitats, causing changes in a number of cultural factors both among the alien people and the indigenous population, today, studying the ethnic history and culture of their people, we, of course, study them in the process of historical transformations and mutual influences of many tribes and peoples, which to one degree or another took part in their formation. Regional ethno-historical research in our time is becoming especially acute, since it is knowledge of the history of one’s own people that helps a modern person to free himself from the narrowness of the nationalist view of the world, to understand the role and significance of the contribution to the common treasury of human culture of all peoples, to realize that humanity is one.

Of course, it is impossible to solve the most difficult issues of ethnic history today without involving data from the most diverse fields of science. It is necessary to combine the efforts of ethnographers, historians, archeologists, linguists, folklorists, anthropologists, art historians, as well as paleobotanists, paleozoologists, paleoclimatologists and geomorphologists, since the development and formation of peoples took place in certain climatic zones, in certain landscapes, with a certain flora and fauna, and this must be taken into account.

Only if the questions posed by ethnic history will be given mutually supportive answers by all of the above branches of science, we can, with a certain amount of confidence, believe that we are close to a true understanding of a particular stage of the historical process. Therefore, at present, the search for an answer to any of the questions of the ethnic history of peoples cannot be considered legitimate without involving data from related sciences.

Viktor von Hen responded very interestingly in 1890 about Russian culture: «Russia is a country of eternal change and completely non-conservative, and a country of ultra-conservative customs, where historical times live, and does not part with rituals and representations, no matter how related. The modern culture here is an external gloss, it develops in a wave-like fashion, generates disgusting phenomena; what the Ancient Tradition has preserved with regard to goods, customs, tools, etc., has been invented solidly, rationally, wisely and skillfully used… They are not a young people, but an old one — like the Chinese. All their mistakes are not youthful flaws, but arise from asthenic exhaustion. They are very old, ancient, conservatively preserved all the oldest and do not refuse it. By their language, their superstition, their disposition, etc. you can study the most ancient times. " («Victor Hen, biography.» 1894.)

The book is a translation of the book by A.G. Vinogradov and S.V. Zharnikova «Происхождение индоевропейцев. Часть 1. Прародина индоевропейцев» in Russian. Published in 2013. All illustrations are taken from the book «Происхождение индоевропейцев. Часть 1. Прародина индоевропейцев».

Chapter 1 Problems of localization of the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans

The problem of localization of the ancestral home of Indo-European peoples has been facing science for a long time. As early as the mid-18th century, the linguistic kinship of European peoples was noted, and in 1767 Kerdu pointed out the proximity of a number of European languages to Sanskrit, the language of the sacred texts of Ancient India «Vedas». «The decisive factor for the birth of Indo-European studies was the discovery of Sanskrit, acquaintance with the first texts on it and the enthusiasm that began in ancient Indian culture, the most striking reflection of which was the book by F. von Schleged» On the language and wisdom of Indians» (1808), — writes V. N. Toporov.

F. von Schlegel, the first to express the idea of a single ancestral home of all Indo-Europeans, placed this ancestral home on the territory of Hindustan, but this assumption was soon proved wrong, since before the arrival of the Aryan (Indo-European) tribes, India was inhabited by representatives of other goy language family and another one-time type — black Dravidians.

Assumed at different times as the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans (today these are the peoples of 10 language groups: Indian, Iranian, Slavic, Baltic, Germanic, Celtic, Romance, Albanian, Armenian and modern Greek): India, the slopes of the Himalayas, Central Asia, Asian steppes, Mesopotamia, Near and Middle East, Armenian Highlands, territories from Western France to the Urals between 60° and 45° N, territory from the Rhine to the Don, Black Sea-Caspian steppes, steppes from the Rhine to the Hindu Kush, areas between the Mediterranean and Altai, in the Western Europe — at present, for one reason or another, most researchers reject it.

Among the hypotheses formulated in recent years, I would like to dwell in more detail on two: V. A. Safronov, who proposed in his monograph Indo-European ancestral home the concept of three Indo-European ancestral homelands — in Asia Minor, the Balkans and Central Europe (Western Slovakia), and T. V. Gamkrelidze and Vyach. V. Ivanov, who owns the idea of the Near-Asian (or rather, located on the territory of the Armenian Highlands and adjacent areas of Western Asia) ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans, detailed and argued by them in the fundamental two-volume book «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans».

V. A. Safronov, addressing the work of N. D. Andreev, emphasizes that on the basis of the Early Indo-European (hereinafter RIE) vocabulary, it can be concluded that «the Early Indo-European society lived in cold places, maybe in the foothills, in which there were no large rivers, but small rivers, streams, springs; rivers, despite the rapid the flow was not an obstacle; they were crossed by boats.

In winter, these rivers froze, and in the spring they flooded. There were swamps… The climate of the «RIE» ancestral homeland was probably sharply continental with severe and cold winters, when the rivers froze, strong winds; stormy sleep with thunderstorms, heavy snowmelt, river spills, hot, dry summers, when the grass was dry, there was not enough water.»

The early Indo-Europeans had early phases of agriculture and cattle breeding, although hunting, gathering and fishing did not lose their significance. Among the tamed animals are a bull, a cow, a sheep, a goat, a pig, a horse and a dog that guarded the herds. V. A. Safronov notes that: «Horseback riding was practiced by the early Indo-Europeans: which animals traveled around, it’s not clear, but the goals are obvious: taming.» Agriculture was presented in a hoe and razor-fire form, the processing of agricultural products was carried out by grinding grain.

The early Indo-European tribes lived settled; they had different types of stone and flint tools, knives, shelters, scrapers, axes, adzes, etc. They exchanged and traded. In the early Indo-European community, there was a difference in childbirth, taking into account the degree of kinship, and juxtaposition of friends and foes.

The role of the woman was very high. Particular attention was paid to the «progeny generation process», which was expressed in a number of root words that passed into the Early Indo-European language from the boreal parent language.

In the early Indo-European society, a paired family stood out, management was carried out by leaders, and there was a defensive organization. There was a cult of fertility associated with zoomorphic cults; there was a developed funeral rite.

From the foregoing, V. A. Safronov concludes that the ancestral home of the early Indo-Europeans was in Asia Minor. He notes that such an assumption is the only possible, because: «Central Europe, including the Carpathian basin, was occupied by the glacier.»

However, paleoclimatology data indicate something else. At the time in question, during the final stage of the Valdai glaciation (the chronological framework of which was established from 11,000 to 10,500 years ago), the nature of the vegetation cover of Europe, although it was different from the modern one, Arctic tundra with birch-spruce woodland, low-mountain tundra and alpine meadows were common in Central Europe, not a glacier. Sparse forests with birch-pine stands occupied most of Central Europe, and steppe vegetation predominated on the Great Middle Danube Lowland and in the southern part of the Russian Plain. Paleogeographers note that in southern Europe the influence of ice cover was not felt, especially in the Balkans and Asia Minor, where the influence of the glacier was not felt at all. Time to which the culture of Asia Minor Chatal Gayuk belongs, connected by V. A. Safonov with the early Indo-Europeans, marked by the warming of the Holocene. Already 9780 years ago, elms appeared in the Yaroslavl region, 9400 years ago linden in the Tver region, and oaks in the Leningrad region 7790 years ago. Moreover, the presence of a cold climate in Asia Minor is unlikely. Here I would like to refer to the conclusions of L. S. Berg and G. N. Lisitsina, made at different times, but, nevertheless, not refuting each other. So L. S. Berg in his work «Climate and Life» (1947) emphasized that the climate of the Sinai Peninsula has not changed over the past 7 thousand years and that here and in Egypt, «if there had been a change, it would rather be towards an increase, not a decrease in precipitation.» He noted that:" Blankengorn believed that in Egypt, Syria and Palestine, the climate in general remains constant and similar to the current one since the end of the pluvial period; the end of the last Blankenghorn refers to the beginning of the interglacial era» (130—70 thousand BC). In a 1921 paper, Blankenghorn writes that «From the Riesz-Wurm interglacial (mousterien of Western Europe) to the present (in these territories), the climate is dry desert, and in the north a semi-desert climate similar to the modern one, interrupted by short humid times corresponding to Wurm glaciation.» G. N. Lisitsina, who writes in 1970, comes to similar conclusions: «The climate of the arid zone in the 10—7I millennia BC is not much different from the modern one.» We have no reason to believe that the climate of the West of Asia Minor, where daphne, cherry, barb are currently growing aris, maquis, calabrian pine, oak, hawthorn, hmelegrab, ash, white and spiny astragalus, animals like mongoose, gyneta, jackal, porcupine, mouflon, wild donkey, hyena, bats and locusts also live, and not every snow falls year, snow cover, as a rule, is not formed», in 8—7 thousand BC so different from the modern one so that it could be similar to the harsh ancestral home of the early Indo-Europeans, which is being reconstructed based on their vocabulary.

In addition, V. A. Safonov writes: «The close relationship between the boreal and the Turkic and Uralic languages, according to N. D. Andreev, allows localization of the boreal community in the forest zone from the Rhine to Altai. It also follows from all areas where the carriers of the RIE could go; Anatolia seems to be the only possible one: the narrow straits did not serve as an obstacle, since the early Indo-Europeans knew the means of crossing (the „boat“ was recorded in the language of the early Indo-Europeans).»

Recall that according to the conclusions of N. D. Andreev: «Of the landscape vocabulary in the boreal parent language, the root words that are somehow related to the forest are most abundant. The image of this series clearly indicates, firstly, the wooded nature of the area where there were tribes who spoke BP, and secondly, the presence of conifers in these forests.»

But a strip of coniferous forests in 10—9 thousand BC it stretched not from the Rhine to Altai (in the latitudinal direction, as suggested by N. D. Andreev and V. A. Safronov after him), but sub-meridially from the southwest (from the foothills of the Carpathians) to the northeast (to Pechora). Consequently, the early Indo-Europeans from this forest zone could begin their movements in all directions (including the territory of Asia Minor), from which, of course, it does not follow that the population of Chatal Guyuk at the end of the 8th-beginning of 7 thousand BC it was not Indo-European. Probably Chatal Guyuk was only a small part of the vast Early Indo-European range. Recall that this time (7 thousand BC) was the peak time of mixed broad-leaved forests reaching the coast of the White Sea in the north of Eastern Europe, and that the early Indo-Europeans for cattle-breeding and agriculture (slash-and-burn agriculture) in combination with hunting, fishing and gathering, very significant territories were needed.

And although V. A. Safronov writes that: «At the beginning of the Mesolithic, the zone of the producing economy was extremely limited,» and it included «only the mountains of Zagros, Southeast Anatolia, Northern Syria, and also Palestine,» on the availability of a producing economy on The territory of Eastern Europe in 7 thousand BC, as noted earlier, is evidenced by archaeological materials obtained in recent years. Referring again to the conclusions of G. N. Matyushin, we emphasize that at the border of 7—6 thousand BC the presence of a domestic horse is recorded in the Southern Urals, and remains of domestic animals (goats, sheep, cattle, horses and dogs) are found on archaeological sites. Recall that it was this set of domesticated animals — bull, cow, sheep, goat, pig, horse and dog — that was recorded in the vocabulary of the early Indo-Europeans. And, of course, a deep kinship, the ancestor of the Early Indo-European Proto-language — the ancient Boreal (Northern) language with the Uralic (Finno-Ugric) and Altai (Turkic) languages naturally follows from the localization of the native tribes of the Boreal language in the era of the Upper Paleolithic finale (15—10 thousand BC) in the zone of mixed and coniferous forests, in Eastern Europe. The migrations of part of the boreal tribes beyond the Urals, to Siberia and to the foothills of Altai are logical and can be explained by the pressure of an excess of population in Eastern Europe during this period, which could be caused by a shortage of hunting grounds during the hunting-fishing type of economy, when the optimal population density was 1 person. 30—40 sq. km.

Such shifts in the subsequent Early Indo-European time could be very significant in all directions and «take away» part of the population of the Indo-European range up to the west of Asia Minor. J. Mellart, the discoverer of the culture of Chatal-Guyuk, noted that already 12 thousand years ago (10 thousand BC) aliens appeared in these areas, the associations of which were «larger and better organized than their predecessors.

These groups of Mesolithic people with their specialized tools, apparently, were descendants of the Upper Paleolithic hunters, however, only in one point — in Zardi, in the mountains of Zagros — materials were found that allow talking about the arrival of carriers of this culture from the north — maybe from the Russian steppes, from for the Caucasus.»

Thus, without rejecting the idea that the population of Anatolia was in 8—7 thousand BC Early Indo-European, who came from the territory of his ancient ancestral home — the forest zone of Eastern Europe, we can assume that most of the early Indo-Europeans continued to live in this very home, which is largely confirmed by the earlier conclusions of the American linguist P. Friedrich that: «the Pre-Slavic best of all other groups of Indo-European languages preserved the Indo-European tree naming system… the speakers of the common Slavic language lived in the ecological zone (per hour completely determined by the flora of wood) similar or identical corresponding zone Indo-European and after-Slavic period carriers of different dialects Slavic substantially continued to live in such an area.»

The zone of mixed coniferous-deciduous forests, we repeat, as early as 7 thousand BC reached the territory of Eastern Europe right up to the White Sea coast.

As for the role of the Early Indo-Europeans in the world historical process, it is difficult to disagree with the main conclusions of V. A. Safronov, which he made in the final part of his work. Indeed: «In solving the problem of the Indo-European ancestral homeland, which has been exciting for two centuries by scientists from many professions and various countries of the world, he rightly sees the origins of the history and spiritual culture of the peoples of most of Europe, Australia, America… How their descendants, the Indo-Europeans of modern times, dug the New World, so the Indo-Europeans of the Ancient World revealed to mankind the knowledge of the integrity of the earthly home, the unity of our planet… These discoveries would remain nameless if the echoes of the great wanderings were not kept in the Indo-European literature separated from us and from these events by millennia… Indo-European travels became possible due to the invention of wheeled transport (4 thousand BC) among Indo-Europeans.» And we add, due to the domestication of a wild horse in the southern Russian steppes already on the borderline 7—6 thousand BC As N. N. Cherednichenko notes: «The spread of a horse from the Eurasian steppes is now beyond doubt… the process of taming a horse is carried out on the distant plains of the Eurasian steppe region… Thus, at present, we can only talk about the ways the penetration of the Indo-European horse breeding tribes of Eurasia to the East and the Mediterranean… Eurasia, therefore, was the territory from where the chariots were brought by the Indo-European tribes to various regions of the Old World, which is very significant but was reflected in the political life of the Ancient East.»

V. A. Safronov writes: «The period of the general development of the Indo-European peoples — the pre-Indo-European period — was reflected in the amazing convergence of the great literatures of antiquity, like the Avesta, Vedas, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Iliad, Odyssey, in the epics of the Scandinavians and Germans, Ossetians, legends and fairy tales Slavic peoples. These reflections of the most complex motives and plots of common Indo-European history in ancient literature and folklore, separated by millennia, fascinate and await their interpretation. However, the appearance of this literature has become possible only thanks to the creation by the Indo-Europeans of the metric of poetry and the art of poetic speech, which is the oldest in the world and dates back no later than the 4th millennium BC… Having created their own system of knowledge about the universe, which opened the way for civilization to humanity, the Indo-Europeans became creators of the most ancient world civilization, which is 1000 years older than the civilizations of the Nile Valley and Mesopotamia. There is a paradox: linguists, having recreated, according to linguistics, the appearance of the pre-Indo-European culture, by all the signs of the corresponding civilization, and determined its oldest in the series of famous civilizations (5—4 millennium BC) could not cross the Rubicon of prevailing historical stereotypes that „light always comes from the East“, and limited themselves to finding the equivalent of such a culture in the areas of the Ancient East (Gamkrelidze, Ivanov, 1984), leaving Europe as a „periphery of Middle Eastern civilizations“… The civilization of the great Indo-Europeans turned out to be so high, stable and flexible that it survived and remained, despite the global cataclysms.»

V. A. Safronov emphasizes that «It was the late Indo-European civilization that gave the world a great invention — wheel and wheeled transport, that it was the Indo-Europeans who created the nomadic economy,» which allowed them to go through the vast expanses of the Eurasian steppes, to reach China and India… We believe that the guarantee The sustainability of Indo-European culture was created by the Indo-Europeans. It is expressed in the model of the existence of culture as an open system with the inclusion of innovations that do not offend the foundations of its structure… As a form of existence with the world, the Indo-Europeans proposed a model that remained in all historical times — introducing factorial colonies into an indo-speaking and foreign culture environment and bringing them to the level of development of the metropolis. The combination of openness with tradition and innovation, the formula of which was found for each historical period of the development of Indo-European culture, ensured the preservation of Indo-European and universal values. «We allowed ourselves such a long quotation, since it is difficult to more clearly, compactly and comprehensively determine the significance of pra-Indo-European and early Indo-European culture for the fate of mankind, than this is done in the work of V. A. Safronov «Indo-European ancestral home.»

Chapter 2 «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans»

The next fundamental work devoted to the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans, the main provisions of which I would like to dwell on, is the work of T. V. Gamkrelidze and Vyach. V. Ivanov’s «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans», where the idea of a common Indo-European ancestral homeland on the territory of the Armenian Highlands and the adjacent areas of Western Asia, from where part of the Indo-European tribes then advanced into the Black Sea-Caspian steppes, develops and is thoroughly argued.

Paying tribute to the very high level of this encyclopedic work, which collected and analyzed a huge number of linguistic, historical facts, data from archeology and other related sciences, I would like to note that a number of provisions postulated by T. V. Gamkrelidze and Vyach. Ivanov, causes very serious doubts. So V. A. Safronov notes that: «The linguistic facts cited by Gamkrelidze and Ivanov in favor of localizing the Indo-European ancestral homeland on the territory of the Armenian Highlands can also receive other explanations. The absence of ie hydronymy in this area can only indicate against localization in it Indo-European ancestral home. Environmental data presented in the parsed work even more contradict such localization.In the territory of the Armenian Highlands there are almost half the animals, trees and plants listed in the list of flora and s listed Gamkrelidze and Ivanov, reconstructed in Indo-European (aspen, hornbeam, yew, linden, heather, beaver, lynx, grouse, salmon, elephant, monkey, crab).»

It is on these environmental data cited in the work of T. V. Gamkrelidze and Vyach. Ivanov, I would like to dwell in more detail. The authors of the «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans» in confirmation of their concept, indicate the oldest names of trees recorded in the ancient Indo-European parent language.

These are birch, oak, beech, hornbeam, ash, aspen, poplar, yew, willow, branches, spruce, pine, fir, alder, walnut, apple, cherry, and dogwood.

As for the Armenian Highlands, at present it is a combination of folded-block ridges and tectonic depressions, often occupied by lakes — closed saline (Van, Urmia), and less commonly — flowing fresh (Sevan). The semi-desert and even desert landscapes are characteristic of the deepest depressions.» Here there are dry feather-grass fescue steppes turning into herbaceous grasses,» in some places in the middle reaches (between 1000 m and 2300 m.) There are dry rare-standing forests of deciduous oaks, pine and juniper.»

In the Iranian highlands, in the mountains of Zagros (on the western slopes and in the wetter northern part, between 1000 m and 1800 m), park oak forests with elm and maple are common, and wild mulberries, poplar, wall oak, and figs are found in the valleys. Due to the fact that in the middle period 1 thousand BC hitherto defined by climatologists as the period of cooling and moistening with respect to the climatic optimum of the Holocene (4—3 thousand BC) and the previous time (7—5 thousand BC), there is no reason to assume in these southern territories there is a much more humid and colder climate of 7—3 thousand BC, the time in question in the work of T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov.

It should be noted that the significant fact is that in the common Indo-European vocabulary there are no names for many trees that are widespread in the Near East and Asia Minor from ancient times. These are:

olive (the primary focus of shaping in Asia Minor);

apricot (which was grown in 4 thousand BC even by residents of Tripoli settlements);

edible chestnuts, known in these territories from the Tertiary period;

quinces, which grows wild in northern Iran, Asia Minor and the Caucasus, where the primary centers of morphogenesis and introduction to culture were located;

loquat, in the wild distributed in the Caucasus, the Crimea and the North. Iran (the primary focus of shaping and introducing into the culture of Asia Minor);

almonds (the primary focus of forming Asia and the surrounding areas);

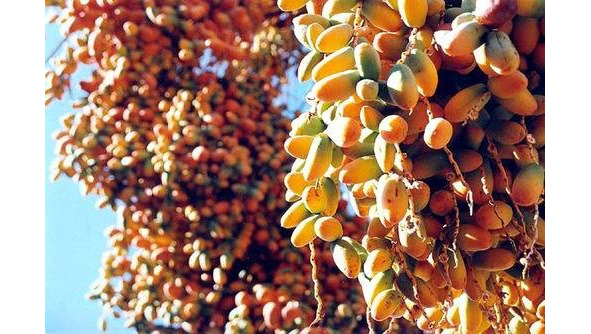

figs or figs, fig trees, found wild in the Near East, Asia Minor and the Mediterranean; and, finally, a date, the primary focus of domestication of which is Southern Iran and Afghanistan, where this plant was introduced into the culture in 5—3 thousand BC.

This list can be greatly expanded. But even in such a fragmented form, he confirms that neither Front, nor Asia Minor, nor the Armenian Highlands could be the oldest ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans. And here again I would like to refer to the conclusion of P. Friedrich that: «the Pre-Slavic best of all other groups of Indo-European languages retained the Indo-European system of tree designation», and «the speakers of the common Slavic language lived in the ecological Slavic period (in particular, defined by wood flora), similar or identical to the corresponding zone of the common Indo-European, and after the general Slavic period, the carriers of various Slavic dialects continued to a significant extent to live in a similar area.»

Chapter 3 Plants of the Indo-European ancestral home

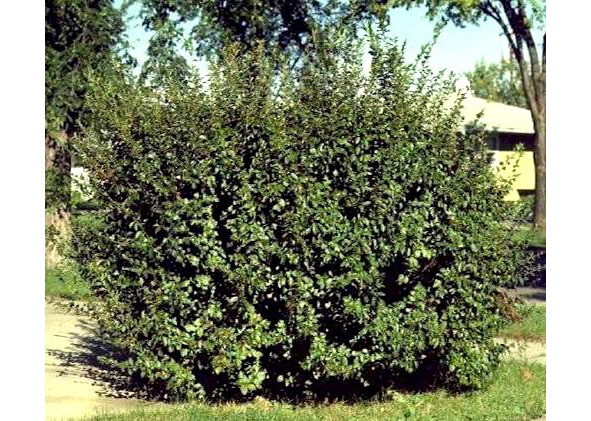

Birch (Betula) (map No. 1), a genus of deciduous monoecious trees and shrubs of the birch family. The bark of the trunks is white or of a different color, up to black. It usually grows rapidly, especially at an early age. It easily populates the free vegetation of space, often being a pioneer breed.

About 100 polymorphic species grow in the temperate and cold regions of the Northern Hemisphere and in the mountains of the subtropics; in the USSR — about 50 species. Many birches matter as valuable forest-forming species; especially warty birch (B. pendula, or B.verrucosa), fluffy birch (B. pubescens), flat birch (B.

platyphylla), ribbed or yellow birch (B. costata), Schmidt or iron birch (B. schmidtii). Most species are photophilous, drought-resistant, frost-resistant, and undemanding to soils. Wood, as well as many types of birch bark, is used in various sectors of the economy. The buds and leaves of warty birch and fluffy birch are used for medicinal purposes.

The most common species is warty birch. Trees reach 25 m. Tall. Birch tolerates some salinization of the soil and dry air, lives 150 years. It occurs in Western Europe up to 65° N., in the USSR throughout the forest and forest-steppe zone of the European part, in Western Siberia, Transbaikalia, Sayan Mountains, Altai and the Caucasus. It grows in a mixture with conifers and deciduous species or in places forms extensive birch forests, and in the forest-steppe zone of the Volga region and Western Siberia — birch spikes interspersed with fields and steppe spaces. Wood is appreciated in furniture production.

T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov believe that this tree grew on the Indo-European ancestral home. «Birch species are currently found throughout the temperate (northern) zone of Eurasia, as well as in the mountainous regions of the more southern zones, where it grows to a height of about 1,500 m. (In particular in the Caucasus, on the spurs of the Himalayas and in the mountainous regions of Southern Europe) In the subboreal period (about 3300—4000 BC), birch was also distributed in the more southerly belt… The presence of a common word for birch in the Indo-European suggests familiarity with the ancient Indo-European tribes, which was possible either in the zone temperate climate (in Europe at latitudes from the north of Spain to the north of the Balkans and further east to the lower reaches of the Volga), or in mountainous regions of the more southern area of the Near East.»

However, academician L.S. Berg in 1947 emphasized that in the northern part of Eastern Europe 13—12 thousand years ago there were forests of birch and pine.

In the warming that began 11—10 thousand years ago, the absolute maximum of birch was noted.

These conclusions are also confirmed by materials prepared by domestic paleoclimatologists for the 12th INCW Congress (Canada. 1987), indicating that in the Vychegda and Verkhnyaya Pechora river basins in layers 45210 +1430 years ago pine and birch prevailed in combination with cereal forbs. In the forests, pine made up 44%, birch up to 24%, spruce up to 15%. In the north of the Pechersk lowland in the postglacial period, i.e. 10—9 thousand years ago, «woody vegetation developed territories» and these were forests of birch, spruce and pine. Data on the Belarusian Polesie indicate that 12,860 +110 years ago (at the beginning of 11th BC) pine-spruce forests and associations of pine-birch forests with an admixture of broad-leaved: oak, elm and linden were widespread here.

Samples of peat from the marshes of the Yaroslavl, Leningrad, Novgorod and Tver regions, performed in the laboratory of the Institute. V. I. Vernadsky, confirm that the peak of birch distribution dates back to about 9800 years ago, 7700 years ago — the absolute dominance of birch.

L. S. Berg wrote: «A study of the history of vegetation in the postglacial period, carried out by analyzing pollen from peat, showed that in the central part of the Union, immediately after the retreat of the glacier, birch and willow appeared in large numbers, and then, in the so-called subarctic time, prevalence passed to spruce and birch; in the next boreal era, birch and pine began to dominate.»

I must say that birch is one of the most important forest-forming species in Eastern Europe since the time of the Mikulinsky interglacial (130—70 thousand years ago) and up to the present day. The authors of the «Paleography of Europe over the past hundred thousand years» note that: «Tracing the Holocene history of birch, we can think that in the modern forests of the European part of the USSR primary birch forests are much more widespread than is usually assumed.» At the same time, nothing testifies to the wide distribution of birch in antiquity in the Near East and on the Armenian Highlands. L. S. Berg emphasized that: «The climatic situation of Palestine at the northern border of palm culture and at the southern limit of grape cultivation has not changed since biblical times.»

The authors of the Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans write: «The main economic value of birch is determined by the fact that it served in antiquity and still serves in separate traditions as material for the manufacture of a wide variety of objects from shoes, dishes, baskets, to writing material in individual cultures, in particular among the Eastern Slavs and in India until the sixteenth century.» A. A. Kachalov points out that: «the inhabitants of the Himalayas use birch bark useful for this purpose in our time.»

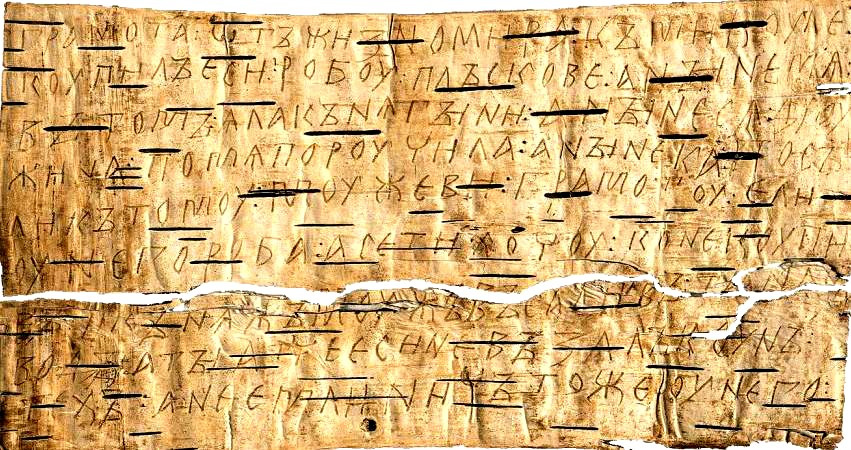

The bark of trees has been used for many millennia among different peoples as writing material on which signs were originally left in the Mesolithic and Neolithic. The use of birch bark as writing material was common in antiquity. The emperors Domitian and Commodus had notebooks from this material, Pliny the Elder and Ulpian report that the bark of other trees was also used for writing. In Latin, the concepts of «book» and «woody bast» are expressed in one word «liber».

Hundreds of Roman letters on birch bark were found during excavations of the Roman fort of Vindoland in northern England. There is evidence of birch bark letters in Sweden and Norway of the 15th century; Swedes used them later. A birch bark letter of 1570 with a German text was kept in Tallinn. The famous Golden Horde manuscript on birch bark and Tibetan medieval birch bark letters from Tuva. In India, Sanskrit manuscripts on birch bark, a number of Buddhist texts on birch bark are known.

«The connection of trees — birch, beech, hornbeam with the terminology of writing indicates the technique of writing and making materials for writing in ancient Indo-European cultures. The emergence of writing and writing is the basis in these cultures for the use of wood and wood material, on which signs or nicks were applied using special wooden sticks. This writing technique, characteristic of a number of early Indo-European cultures, reflects, obviously, a typologically more archaic degree of writing development than carving signs on stone, or putting them on clay tablets, or on specially treated animal skin.»

I must say that it is difficult to imagine that a simpler, more affordable, maneuverable and less laborious letter on birch bark was more archaic (or primitive) than an inconvenient, bulky letter on clay tablets or inscriptions on stone. Indeed, if there were both clay and birch bark from the early Indo-Europeans, they would hardly have switched from writing on birch bark to using clay tablets for business correspondence or for business records.

In addition, the question arises why birch bark, as a material for writing, was preserved precisely in the East Slavic and Indian ethnic range. If you follow the findings of T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov, the Slavic and Indo-Iranian branches of the Indo-European community dispersed even on the territory of their supposed common ancestral home in Asia Minor (where there are practically no birches). The Pre-Slavs went to Eastern Europe, and the Indo-Iranians moved to Iran (where birch is not common) and Hindustan, where only in the Himalayas at an altitude of 2500—4300 m. grows «useful birch», «Jacquemont birch» and, finally, the birch of the section of acuminatum lives — a tree 20—30 m. high with very large leaves. But these trees are not widespread in India and are considered endonomics of a very narrow range.

But in the Indian tradition, birch bark is not just writing material, but sacred material: on birch bark (and only on birch bark) a record was made of marriage in the higher castes, and without this record on birch bark, marriage was not considered valid. This situation could not develop in areas where birch is almost not widespread. Birch bark could become material only where birch has been one of the main forest-forming species for many millennia — in the forest strip of Eastern Europe. It makes sense to pay attention to the following circumstance. T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov emphasizes that birch bark was used for writing in the most ancient Indo-European cultures and was preserved in such quality among the Eastern Slavs and in India until the 16th century.

But the ancestors of the East Slavic peoples and Aryan peoples of North-West India diverged in the middle of 2 thousand BC Nevertheless, birch bark, as a material for writing, was preserved precisely among the Eastern Slavs and Indians.

It follows from this that birch bark was still on their common ancestral home as a material for writing. But then the conclusion is also natural that long before the middle of 2 thousand BC the ancestors of the eastern Slavs had writing and the predecessors of the Novgorod and Pskov birch bark letters were older than them for many millennia. It is also interesting that in the North Russian tradition birch bark and in the 19th century (as in India) was precisely sacred material for writing.

This is evidenced by the story of an outstanding ethnographer of the 19th century.

S. V. Maksimov about the birch bark book, which the Archangel old man-Pomor, ready to give any other manuscript, decorated with miniatures, Old Believers book, did not want to sell him for any money.

S. V. Maksimov notes that this book, «written by half-mouth» on birch bark, «finely and successfully stripped and assembled, stitched in quarters… The written was disassembled as conveniently as the written on paper, the letters did not spread out, but stood straight, one beside the other: another paper makes letters worse…

the book was somehow twisted into simple, birch bark, planks… (to write such a book) sticky soot is made from burnt birch peel, which, when diluted on the water, gives decent ink at least those that can leave a very noticeable mark on their own, if they are wiped over the top layer. The eagles and wild geese, which are many on the tundra and which are difficult to fly away from the well-aimed shot of the usual hunters, give good feathers always conveniently peeling over the layers of birch bark, which can be turned into pages and on which you can write soon and, perhaps, clearly, «writes S. V. Maksimov.

The sacred nature of birch bark, as a material for writing, is evidenced by the customs preserved in the Russian North almost to the present day. So A. A. Veselovsky in his «Essays on the History of the Life and Work of Peasants of the Vologda Province» describes the rite of «unsubscribing,» in which the healer, when whispering, writes a note and puts it into the wind and it becomes easier for the patient. «They write a petition on birch bark and it is carried away by «wind-father».

From the same series, it is customary to write conspiracies and letters to the devil — «bondage» — on birch bark, and the text is not written (in the literal sense of the word), but is applied by soot in the form of erratic strokes, oblique crosses, winding lines, etc. All this testifies to the now anciently forgotten, supplanted Cyrillic alphabet, the ancient Slavic writing system. Perhaps her relics are mysterious signs on the manure of northern Russian icons and the so-called «ornaments» painted by Dionysius on the arch of the portal of the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Virgin in the village of Ferapontovo.

Oak (Quercus) (map No. 2), a genus of deciduous or evergreen trees, rarely shrubs of the beech family. The leaves are alternate, simple, cirrus, lobed, serrated. The fruit is a single-seeded acorn, partially enclosed in a cup-shaped woody bun

Oak grows slowly. Photophilous. Some species are drought-tolerant, quite winter-hardy, and less demanding on soils. About 450 species in the temperate, subtropical and tropical zones of the Northern Hemisphere. In the USSR — 20 wild species in the European part, in the Far East and the Caucasus; in culture 43 species.

English or summer oak (Q.robur) — a tree up to 50 m high. It survives up to 1000 years. Distributed in the European part of the USSR, in the Caucasus and almost throughout Western Europe. In the northern part of the range, it grows along river valleys, to the south reaches the watersheds and forms mixed forests with spruce, and in the south of the range — pure oak forests; in the steppe zone it is found along ravines and gullies. One of the main forest-forming species of broad-leaved forests of the USSR. Rock or winter oak (Q.petraea), found in the west of the European part of the USSR, in the Crimea and in the North Caucasus. Georgian oak (Q. iberica) grows in the eastern part of the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia; in the alpine zone of these regions, large anther oak (Q.macranthera) grows. The main species of the valley forests of the East Caucasus is the long-legged oak (Q. longipe). An important forest-forming species in the Far East is Mongolian oak (Q.mongolica), a frost-resistant and drought-resistant tree.

Wood has high strength, hardness, durability and beautiful texture. Used in shipbuilding, underwater structures, as does not give in to decay; it is used in furniture, carpentry, cooperage, building houses, etc. Some types of bark (Cork oak — Q.suber) give cork. Bark and wood contain tannins used to tan leather. The dried bark of young branches and thin trunks of oak oak is used as an astringent in the form of a water decoction for rinsing in inflammatory processes of the oral cavity, pharynx, pharynx, as well as lotions in the treatment of burns. Acorns go to feed for pigs.

T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. B. Ivanov believe that the early Indo-Europeans could get to know this tree only in the southern regions of the Mediterranean (including the Balkans and the northern part of the Middle East), because «oak forests are uncharacteristic of the northern regions of Europe, where they spread only from the 4th-3rd millennium BC.»

However, it is now known that oak forests were widespread in northern Europe (and Eastern Europe in particular) during the Mikulinsky interglacial period (130—70 thousand years ago). During the peak of the Valdai glaciation (20—18 thousand years ago), in a number of areas of the Russian Plain there were forests with the participation of broad-leaved species such as oak and elm. At the beginning of 11 thousand BC (12860 +110 years ago) in the Belarusian Polesie there were widespread associations of pine-birch forests with an admixture of broad-leaved: oak, elm and linden. During the Mesolithic, a significant part of the territory of modern Vologda and Arkhangelsk regions was covered with deciduous forests, which include oak forests. S. V. Oshibkina notes that at the Mesolithic site of Pogostishche-I in the East Prionegie (7 thousand BC), the forest consisted of birch, pine, a small amount of spruce and mixed oak forest. L. S. Berg noted that as early as 9—8 thousand BC «in the Neva basin separate pollen grains of broad-leaved species and hazel» appear, and in 5—4 thousand BC here noted «the great distribution of oak forests with linden, elm and hazel.»

The conclusions of L. S. Berg are confirmed by data obtained by domestic geochemists in 1965. So it is noted that, starting from the turn of 7—6 thousand BC «pollen spectra are characterized by a high content of broad-leaved pollen… The climax points of the curves of oak, elm, hazel and alder are located here.» We emphasize that the culmination of the distribution of oak in the Tver region dates back to 6945 years ago (the beginning of 5 thousand BC), and in the Leningrad region — to 7790 years ago (the beginning of 6 thousand BC). In addition, in the Neolithic and Bronze Age, it was in Eastern Europe that the largest oak forest zone in Europe was located.

Thus, the thesis about the presence of oak forests in ancient Indo-European time only in the Mediterranean, mountainous areas of Mesopotamia and adjacent areas is completely groundless.

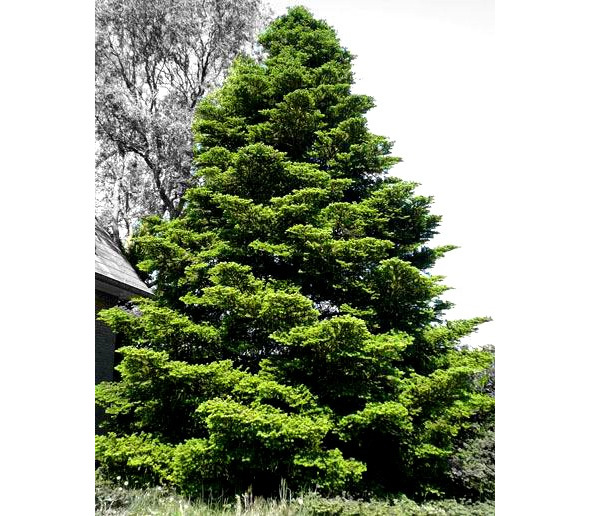

Beech (Fagus) (map No. 3), a genus of monoecious plants of the beech family. Trees up to 50 m high with smooth gray bark. 10 species in extratropical regions of the Northern Hemisphere; in the USSR — 3 species. Acorn fruits (nuts) are provided with a woody shell. Beeches are shade-tolerant, but heat-loving. In the mountains they rise up to 2300 m. They form clean or mixed forests. They live up to 400 years.

The wood is dense, heavy, well polished; in air it is quickly destroyed, but in water and in the wet states it is very durable; used for the manufacture of musical instruments, furniture. The fruit contains poison, which decomposes upon frying; oil is made from fruits.

The authors of the «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans» note that the name «beech» is not in the Indo-Iranian languages. This is more than strange if we accept the hypothesis of V. V. Ivanov and T. V. Gamkrelidze about the Near-Asian ancestral home of Indo-Europeans. After all, this tree was in ancient times one of the main forest-forming in the Transcaucasia and Western Asia. The fact that the ancient Indo-European name of beech has not been preserved in the Indian language can still be explained — there is no beech on the territory of Hindustan.

But how could the Iranians lose this ancient Indo-European name if the beech is the main forest-forming not only in the Near East and the Armenian Highlands (the supposed oldest ancestral home), but also in the Iranian Highlands — the new homeland of the Iranians (according to T.V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov)?

After all, G. I. Tanfiliev, the chief botanist of the Imperial Botanical Garden, an outstanding phytogeographer and connoisseur of the flora of Russia, describing the vegetation of the Caucasus in 1902, noted that the forests here consist mostly of beech mixed with chestnut and oak. At present: «in the Caucasus, beech occupies almost half of the total area covered by forests. It is widespread on the northern slopes of the Caucasus, in Transcaucasia it is characterized by almost continuous distribution, and only in the upper reaches of individual rivers gives way to conifers. It runs along the main ridge from the Black Sea coast to the eastern border of the forests (Shemakha), through the Lesser Caucasus, goes east to the Terter River, and in the east it is again found in Talysh, leaving the foothills of Elbrus to Iran.»

The same picture was observed in antiquity: pollen analysis of samples from the bottom of the Black Sea, dating from the beginning to the middle of 6 thousand BC, when there was a rapid filling of the freshwater Black Sea with salt water from the Bosphorus, indicate the presence of forests in this area from hornbeam, beech, oak and elm.

Apparently, the picture has not changed to this day. But then it is absolutely inexplicable how the ancient Iranian tribes, who came from their alleged Near-Asian ancestral homeland with its beech forests to the territory where beech forests also prevailed and still prevail, the ancient Indo-European name of this tree completely lost.

Probably, such a situation could only develop if the ancient Iranians came to the territory of the Iranian Highlands from areas where the beech does not grow.

And here it is appropriate to recall that, as noted by T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov: «the beech is absent to the north-east from the Black Sea to the lower reaches of the Volga throughout the entire postglacial period.»

Hornbeam (Carpinus) (map No. 3), a genus of deciduous trees, rarely shrubs of the hazel family. A trunk with smooth gray bark. The fruit is a single-nested, single-seeded nutlet with a leaf-shaped wrapper. About 50 species in Europe, East Asia and North America. There are 5 species in the USSR — in the West of the European part, in Crimea, in the Caucasus and in the south of Primorsky Krai. The hornbeam does not tolerate boggy and acidic soils. Heavy, hard wood is used in the manufacture of weaving shuttles, musical instruments, and in mechanical engineering.

The most common hornbeam (C. betulus) and Caucasian hornbeam (C. caucasicus). Trees up to 30 m high. Frost-resistant. Trees begin to bear fruit from the age of 20 (yield of nuts up to 1.5 tons per 1 ha). In the Crimea and the Caucasus grows the eastern hornbeam, or meadowsweet (C. orientalis), a shrub or 32 tree with smaller leaves. The hornbeam grows in the Near East, makes up a significant part in the forests on the western shore of the Caspian Sea and dominates together with the oak in Karabakh.

In the Caucasus, in Southern and Eastern Europe (pure hornbeam forests are known only to the east of the Vistula and in the upper Bug), in Asia Minor and Iran, the eastern hornbeam or hornbeam grows in the lower, less often middle belt of mountains to a height of 1200 m. But, like beech, throughout the postglacial period to the north-east of the Black Sea, the hornbeam is absent. And with this tree, whose ancient Indo-European name is in many Indo-European languages, but not in the Indo-Iranian ones, a situation similar to «beech» has developed.

Yew (Taxus), (map No. 3), a genus of coniferous evergreen trees and shrubs of the yew family. Cones contain 1 seed, surrounded by a red fleshy seedling and resembling a berry in appearance.

About 10 species distributed in Europe, Asia Minor and East Asia, the Caucasus, and North America. In the USSR, 2 species, yew berry, or non-purulent-tree (T. baccata), grows in Belovezhskaya Pushcha (Western Belarus), Bukovina (Western Ukraine), Southern Crimea, and the Caucasus. Tree up to 27 m high.

Shade tolerant. Lives up to 3 thousand years. Its solid, durable, reddish-brown wood is highly regarded and used in furniture manufacturing and for turning. The whole plant is poisonous especially for horses. Yew-pointed, or Japanese (T.cuspidata), grows in the Far East, in China (Manchuria), Korea and Japan. Tree up to 20 m high; gives valuable wood (mahogany or rosewood).

This ancient Indo-European name also does not exist in the Indo-Iranian languages.

«Yew is spread in Europe from Scandinavia to the mouth of the Danube, its eastern border roughly coincides with the border of beech… Yew in historical times is not found in Eastern Europe and the Northern Black Sea… yew is especially common in the more southern regions of the Caucasus (starting from the North Caucasus), Asia Minor and parts of the Balkans, «writes T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov.

The situation is repeated again, similar to the «beech» and «hornbeam». Yew is growing in the alleged Near-Asian ancestral homeland, is also widespread in the new Iranian homeland, and there is no Indo-European name for this tree in the Indo-Iranian languages, just as it was not in historical time in Eastern Europe and the Northern Black Sea region.

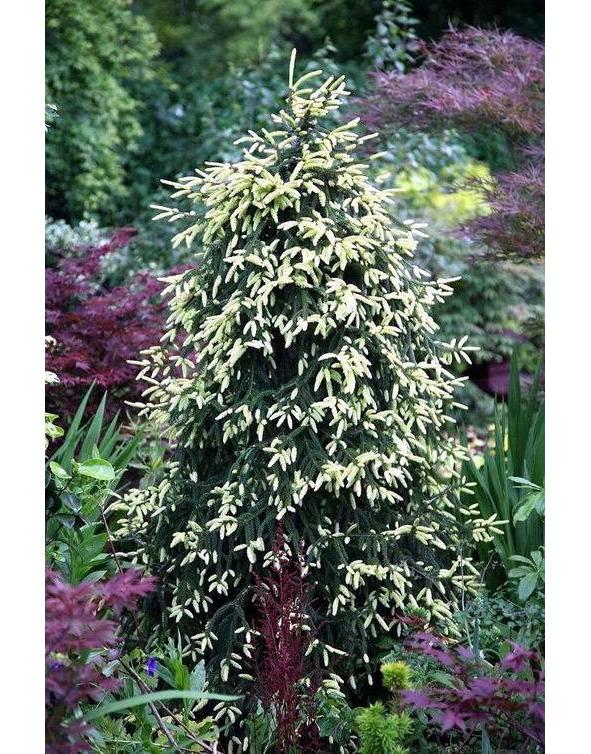

Fir, spruce, pine (map 4). Fir (Abies), a genus of evergreen conifers of the pine family. The trunk is straight, up to 80 m high, with a thick, usually conical crown. The bark is smooth with nodules — containers of resin. The leaves are linear, flat, at the apex for the most part blunted, below with two light strips along which the stomata are located.

About 50 species; grow in the mountains, less often on the plains of the Northern Hemisphere. In the USSR — 9 species and approximately 16 species introduced. Valuable resins are obtained from the bark.

In the USSR, Siberian fir (A. sibirica) is most common — in the north of the European part and in Siberia, on the plains and in the mountains (to the upper border of the forest). A slender tree up to 30 m. high. Fir balsam is obtained from the bark, fir oil is obtained from needles and branches.

In the Caucasus, a relict species of Caucasian fir, or Nordmann fir (A. nord-manniana), a tall (up to 50 m) tree with a lowered crown, grows. Lives up to 500 years.

In Europe, white fir (A. alba) grows, giving valuable wood.

T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov indicate that «fir in its various forms has been known since the Middle and Late Atlantic period (7—4 thousand BC) in the Transcaucasia and Western Asia, as well as in the lower reaches «Volga, in Eastern Europe, in the Pripyat-Desna basin. Later, fir is pushed aside by some other species of trees, preserved mainly in the mountainous regions of Europe, the Caucasus, Western Asia and Eastern Europe.»

But I would like to emphasize that even during the peak of the Valdai glaciation, when, unlike Western Europe, «within the Russian plain, forests occupied a large area in the form of a wide strip crossing it in the direction from the south-west to the north-east», they were represented mainly by birch-pine and spruce-fir forests. At the same time: «Regarding the nemoral and subtropical shrub-forest types of vegetation, the following should be noted: the fact that these types were preserved in the south of Europe during the Valdai glaciation era clearly indicate the results of the florocenogenetic analysis of modern vegetation of the Mediterranean countries.»

How in such a situation, when the climate of Asia Minor has not practically changed from the time of the Valdai glaciation to the present day, fir could be pushed to the mountainous regions of Europe, the Caucasus and, most importantly, Asia Minor, where it is currently not available. According to modern vegetation maps in the Old World, the range of the fir genus is the northeast of the European part of Russia, Siberia, China (northwest), slightly in the Caucasus and the Western Mediterranean.

G. I. Tanfilyev noted that: «Siberian species enter the European taiga, except for larch, also fir and cedar. Of these, cedar grows on this side of the Urals in small groups and separate trees among forests and other species, while larch and fir even form forests in places.»

Currently, fir occupies 12 million hectares in Russia. Thus, there is no certainty that fir grew in antiquity in Asia Minor, but the fact that it had and has an extensive range in northeastern Europe and in Siberia is a fact.

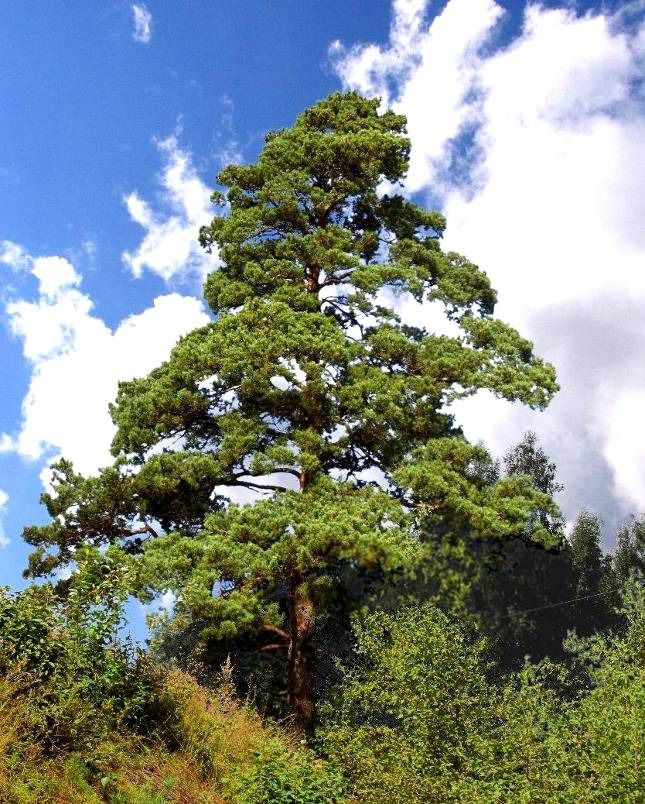

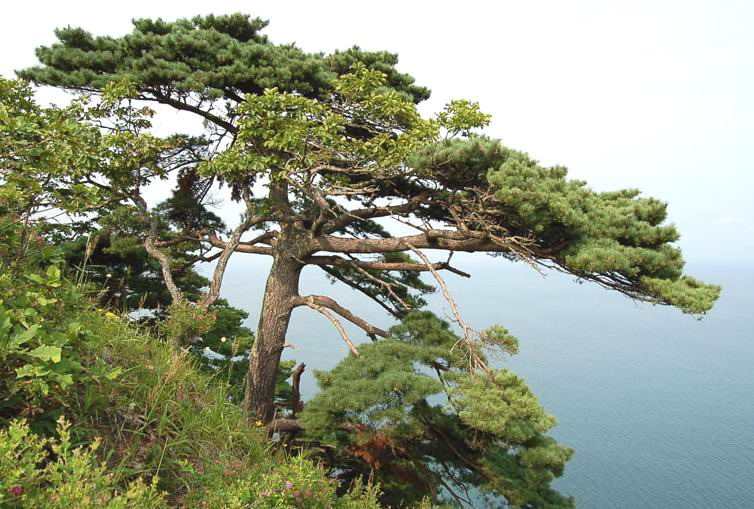

Pine (Pinus), a genus of coniferous evergreen trees and creeping shrubs of the pine family. Height 1.5—75m. Needle needles. Pines are photophilous, form forests and groves on well-drained soils and rocky slopes, but can also grow in wetlands.

They live up to 350 years. About 100 species in the forest zone of Eurasia and North America, less often in the mountains of the tropics of the Northern Hemisphere.

There are about 12 species in the USSR. Scots pine (P.silvestris) forms forests in the European part and Siberia. A tree 40 m high. It provides timber and ornamental wood, fuel, resin, var, turpentine, turpentine essential oil, rosin. From the needles get vitamin C.

On the Kola and Scandinavian peninsulas, the Lapland pine (P.lapponica), close to it, grows in the mountainous parts of the Crimea and Western Transcaucasia — the Crimean pine, or Pallasiana (P. pallasiana).

In Transcaucasia, the Pitsunda pine (P. pityusa) is known.

Siberian cedar pine, cedar dwarf pine, and Korean or Manchurian pine (P. koraiensis) grow in the USSR. It grows in the Far East, in the mountains of Manchuria, northeast of Korea and in Japan (Honshu Island).

V.V. Ivanov and T. V. Gamkrelidze write that pine and its varieties from ancient times are represented in the mountainous regions of the Caucasus and the Carpathians, as well as in the Black Sea region.

But it should be noted that in ancient times, pine was spread by no means only in these territories. So, at the peak of the Valdai glaciation in the Oka basin, spruce-pine forests of the north-taiga type were noisy, in the middle reaches of the Desna forests with spruce and Siberian cedar pine were locally distributed.

According to paleogeography in the ancient Holocene (2 thousand years ago), spruce, pine and alder were present in the forests of the Vologda Oblast. A similar situation was in other areas of the central part and the north of Eastern Europe. In general, conifers began to play a significant role in the vegetation cover of Eurasia since the Triassic period, which began about 240 million years ago.

«Among modern conifers, the most ancient families are Araucariaceae, Podocarpaceae, and especially pine… plant residues (including pollen grains), more or less confidently related to the genus pine, are known from Jurassic deposits.

Currently, forests with a predominance of pine are most pronounced in the northern regions of Eurasia and North. America. Pine forests in Russia occupy an area of 108 million hectares.

The range of the genus pine is the whole of Europe, Siberia, the Himalayas, the Pamirs, China, Japan, and Asia Minor. In Western Asia there is no pine.

Pine forests are not as significant as T.V. Gamkrelidze and Vyach. Sun Ivanov, and in the Caucasus. So G. I. Tanfilyev, describing the forests of the Western Transcaucasia, notes that: «Very characteristic of the coast, found only at the very sea, is a seaside pine tree, a tall tree growing in small groups between Novorossiysk and Cape Pitsunda, and only at this last point it forms a large forest.»

He notes that «in the forests on Talash there are no conifers at all, except yew and juniper,» and «in the East Caucasus, only pine and juniper are found from coniferous species, of which pine, however, goes only to the meridian of Elisavetpol.»

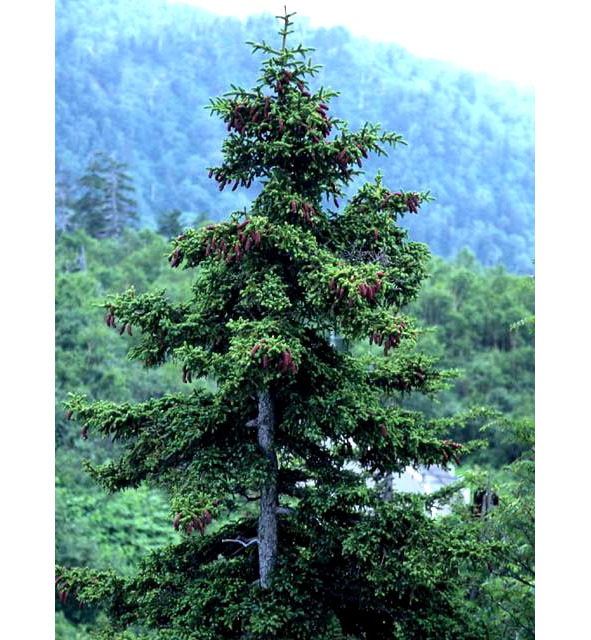

Spruce (Picea), a genus of coniferous evergreen trees of the pine family. The most important forest-forming breed. Shade-tolerant spruce, winter-hardy, suffers from dry air. He lives 300 years. About 40 species — in Europe, Asia, North America. There are 8 species in the USSR. In the European part, from the northern border of the forest to the northern border of chernozem, common spruce, or European (P. abies, go P. excelsa), grows 20—50 m. high. The wood is white, light and soft, used in construction. Resin, tar, turpentine, rosin, wood vinegar, tannins are extracted from it.

In the north of the European part, the Urals and Siberia, it is replaced by Siberian spruce (P. obovata). Finnish spruce (P. fennica) lives in North Karelia, East spruce (P. orientalis) in the Caucasus, Shrenka spruce (P. schrenkiana) with bluish needles in the Dzungarian Alatau and Tien Shan, and Korean spruce (P. koraiensis) and ayan spruce (P. ajanensis).

Fir-tree Korean Fir-tree ayan The authors of the «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans» argue that: «In ancient times, spruce was represented only in the highlands, in particular in the Caucasus and in the mountainous regions of Central and Southern Europe.»

However, L. S. Berg believed that spruce forests prevailed in the north and in the center of Eastern Europe 11—10 thousand years ago; 9—8 thousand years ago, behind the amount of spruce, it fell slightly; 7—6 thousand years ago, in a temperate, warm and humid climate, the secondary distribution of spruce began. «In 1 thousand BC in colder and wetter conditions, spruce begins to penetrate into oak forests. The botanical data indicate that at present «most species and individuals of spruce are kept in an area whose southern border does not extend beyond 35 °N, with the vast majority of spruce stands far north.»

And moreover, even during the maximum of the Valdai glaciation (18—20 thousand years ago), it was from 55 to 63° N that were widespread in Eastern Europe. meadow steppes with birch and spruce forests. As for the Caucasus, spruce is widespread here «mainly in the west of the Greater Caucasus, both on its northern slopes and in the Caucasus, reaching almost Tbilisi in the East. The southern and southeastern border of the eastern spruce lies in Anatolia.»

Thus, the prevailing range of the spruce genus is the north of Eurasia, the Himalayas, China and some of the Balkans, Asia Minor and the Caucasus, i.e. the thesis that in ancient times spruce was represented only in high mountain regions, in particular in the Caucasus and in the mountainous regions of Central and Southern Europe, seems incorrect.

Cornel, Dogwood (Cornus) (map No. 5), a genus of trees and shrubs of the cornel family. Fruits — red fleshy drupes on legs. 4 species in Central and Southern Europe, Asia Minor, Central China, Japan and North America. The genera of derain, dogwood, Svidina and some others are united under the name dogwood.

Doeren (Chamaepericlymenum), a genus of plants of the cornel family. Low shrubs with underground creeping woody rhizomes and grassy annual stems. Fruits are red drupes. 3 species: in Europe, the Far East and North America. All are found in the USSR.

T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov write in their work that: «Cornel is distributed mainly in the relatively more southern regions of Europe, the Caucasus and Western Asia.»

Currently, 15 species of wild dogwood are growing in our country, among them: Holly dogwood, reaching the European part to Arkhangelsk, where it bears fruit in the same way as in the Crimea; brushwood cotoneaster, common in Crimea, the Caucasus and Western Asia, also bearing fruit to the latitude of Arkhangelsk; cotoneaster whole or ordinary, growing in the Baltic states, Western Belarus, the Caucasus, Ukraine, Crimea and Central Asia, and also reaching Arkhangelsk; black-fruited cotoneaster, common in Eurasia from Central Europe to China, and from Lapland to the Caucasus and Central Asia, growing everywhere except for the tundra and rain-fed deserts.

Fruits are eaten raw, for jam, compotes. Solid heavy wood is used for various crafts. Dogwood contains tannins. Good honey plant.

In addition, dogwood varieties are widely distributed under the general name Derain, about 50 species of which grow in temperate climates. This is Siberian white Derain (white swine, connecting rod), growing in the north of the forest strip of the European part of our country, in Siberia and the Far East. This shrub prefers wetter and wetter places along the banks of rivers, lakes, river floodplains and does not grow in the south of the steppe zone.

Red Derain (blood dogwood) is distributed throughout the European honor of Russia, except for the far North and Caucasus, as well as central and southern Europe. This shrub lives in floodplains, thickets, undergrowth, and forest edges.

Common Derain — dogwood, spread to the north to the city of Orel. Swedish Derain (Ch. Suecicum) grows in the north of the European part of the USSR and in the Far East;

Canadian Derain (Ch. Canadense) and Unalashkin Derain (Ch. Unalaschkense) — in the Far East.

Thus, to argue that dogwood is in 5—4 thousand BC grew only in the southern regions of Europe, the Caucasus and Asia Minor, it is hardly possible.

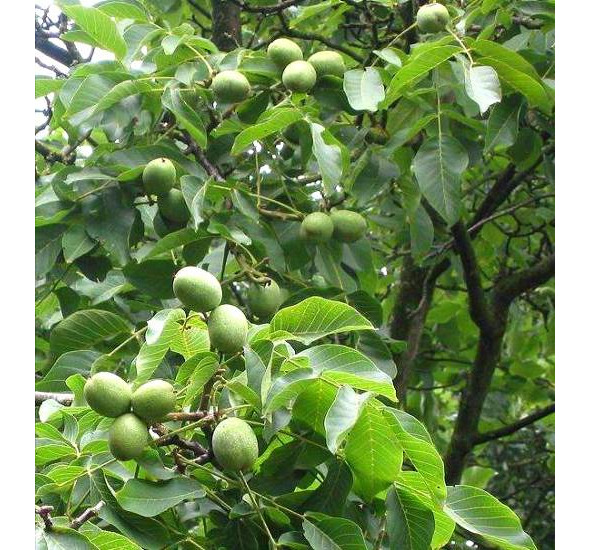

Walnut (Juglans) (card No. 6), a genus of plants of the walnut family.

Deciduous monoecious trees with large unpaired pinnate leaves. Flowers — in the axils of the covering leaves; stamen — in hanging multi-flowered catkins; pistillate — in small-flowered apical inflorescences. The fruit is stone-fruit, with a green fleshy outer shell and a hard, ligneous inner. Edible seed, without endosperm. 14—40 species growing in mixed broad-leaved forests, mainly in the mountains of southern Europe, Asia and America. Many species have been bred since ancient times for the sake of nutritious tasty fruits, to obtain valuable beautiful wood. In the USSR, 2 species grow wildly: walnut and Manchu walnut.

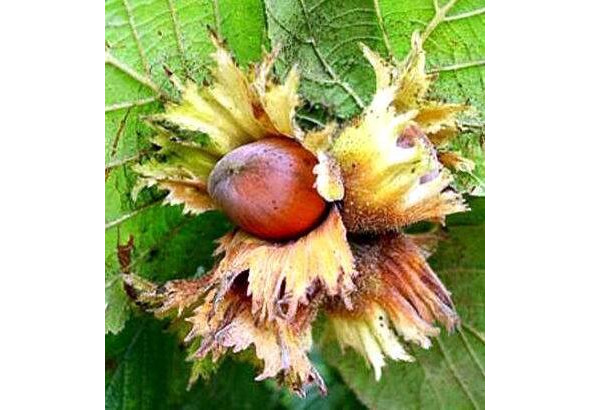

In the USSR, 9 types of hazelnut are common: ordinary, variegated, Manchurian, short-tubular, large-fruited, Pontic, Colchis, Imereti and bear nuts.

Variegated, short-tubular and Manchu hazel grow in the Far East. Pontic, Colchis, Imereti hazel grow in Transcaucasia. Large hazel, or hazelnuts, has become one of the founders of large-fruited garden forms. All of the listed hazel species, except for a bear nut, are tree-like shrubs 5 to 8 meters high.

The bear nut develops into a mighty tree up to 25 meters high. It competes with beech in beauty and power, lives up to 200 years. A bear nut gives up to 20 tonn of fruit. The wood of this tree, growing in the Caucasus and in the southwestern regions of the USSR, is highly regarded.

In forestry, hazel, or hazel, is of greatest importance. This multi-branched shrub 5—8 meters high grows in coniferous-deciduous and broad-leaved forests of the European part of the USSR. Fruits are single-seeded nuts with a tight shell.

Nuts ripen in August-September. Separate bushes give up to 10 kilograms. Almost the yield of thickets is up to 500 kilograms of nuts per hectare. Harvest years are constantly alternating with low-yielding.

Hazel is easily propagated by mature nuts, rooting of shoot branches, perennial shoots and dividing bushes. Nuts during autumn sowing to a depth of 5 centimeters rise well next spring. The kernel of the nut contains 55—70% fat, 14—18% easily digestible proteins, 2—5% sucrose, B and C vitamins, iron salts and trace elements. Kernels are eaten raw, dried and fried. Flour from nuts has been stored for more than 2 years, without losing its taste and nutrition.

By caloric content, kernels are superior to white bread and meat. (1 kg. Hazel kernels — 5840, pork — 3860, rye bread — 1960, potatoes — 860 kcal). In peanut butter, 65% oleic, 9% palmetic and 1% stearic acid. The vitamin content is also high.

The hazelnut oil is delicious, reminiscent of almond. It is used for the production of cosmetics, as well as in painting.

Hazel wood is light, flexible, strong, and white with a pinkish tint, small-layer, and glossy. Coal from wood is suitable for the manufacture of gunpowder.

Winemakers need sawdust. Bark and leaves are used in the leather industry.

Hazel pollen is a good bribe for bees.

Already 7—6 thousand years ago (the Atlantic period) in the northern and central part of Eastern Europe, «a large distribution of oak forests with linden, elm and hazel.» «In the loch-like loam of Likhvin there were pollen grains of hazel, but this time is 10—11 millennia from us, that is, VIII — IX millennium BC…»

Paleoclimatologists note that in the second half of the boreal period (which ended 7700 years ago), i.e. at the beginning of 6 thousand BC in these areas, a significant amount of hazel pollen appears, the culmination of which refers to the Middle Holocene (5700—5000 BC), and hazel accounts for 5% of the total species composition.

The assertion of T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov that the name of the nut in the common Indo-European vocabulary is related specifically to walnuts does not seem very convincing. Although the walnut is endemic to the south, the ancient Romans called it Jovis glans, i.e. Jupiter’s Acorn. And, although the walnut grows wild in Greece, it is believed that it went wild there. The range of wild walnuts is southern Kazakhstan, Central Asia, Iran, Afghanistan, the western parts of the Himalayas and Tibet, and southeast Transcaucasia (Talysh).

N. I. Vavilov wrote that: «Afghanistan as a whole is included in the general range of wild walnuts… in Asia Minor and Europe, wild walnuts should be considered descendants of wild cultivated plants… In western Georgia, huge walnut forests are rightly regarded as overgrown ancient gardens abandoned during the «Georgian-Persian and Georgian-Turkish wars.»

At the same time, wild hazel in Russia today occupies 3 million hectares, and gives a total yield of nuts from 6 to 12 million tons per year. As for the walnut, in its original area (Central Asia), it occupies only 100 thousand hectares. In addition, Pontic Hazel is an endemic of the Pontus Mountains in Asia Minor, where it has been known since ancient Greece as a nut culture («Heracles nut») and is the ancestor of the famous Turkish («Byzantine») walnut varieties.»

Thus, it is hardly possible to postulate the name of a nut in the common Indo-European language as walnut, given the concept of the Near-Asian ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans, because Front Asia is not the original habitat of its wild forms. It can be assumed that the name of the nut in the common Indo-European language is not associated with «walnut», but with the hazelnut plant native to Europe.

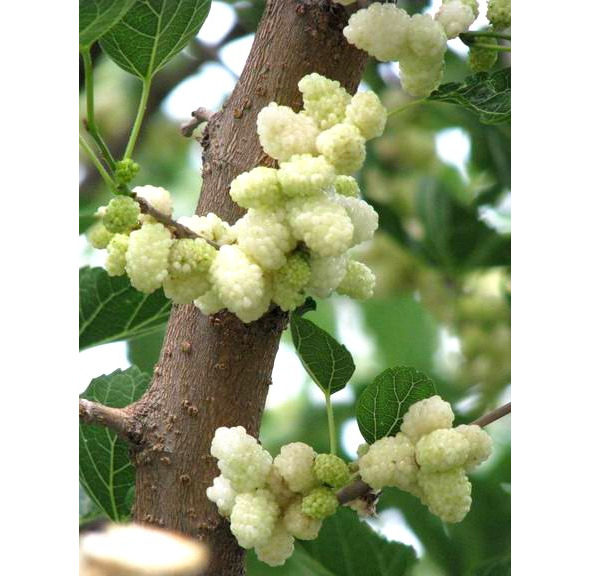

Mulberry, mulberry tree (Morus) (map No. 7), genus of trees of the mulberry family (Moraceae). Height 35 m., Crown spherical, broadly egg-shaped, very dense. The bark is brown, fissured. The fruit is a false, complex, juicy drupe, mulberry, up to 5 cm long, white, pink, dark violet, almost black. About 24 species, in East and Southeast Asia, and in southern Europe, in southern North America and northwestern part of South America, partly in Africa; in the USSR — 4 species in the south of the European part and in Central Asia.

Grown for the sake of obtaining leaves for feeding silkworm, as well as fruits.

The fruits are sweet or sweet and sour (10% sugar), used for food in fresh and dried form, as well as for making wines. The wood is dense, elastic, heavy, and is used as a building and ornamental material in carpentry and cooperage. To feed the mulberry silkworm, white mulberry (M.alba), silkworm (M. bombycus), multilobular mulberry (M.multicaulus) are cultivated, and black mulberry (M.nigra) is also used to produce fruits. Mulberry is drought-resistant, relatively undemanding to soils, salt-tolerant, and resistant to waterlogging.

A very interesting situation is developing among the authors of the Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans and with the name of the mulberry tree. T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov note that the «mulberry tree» with dark fruits is a characteristic fruit tree of the Mediterranean and South-West Asia; Western Asia is considered its ancient homeland. Large fruits… in a number of highlands of Central Asia and Central Asia (in the Pamirs) are used for food (flour is replaced from dried mulberry fruits, replacing flour from grain), leaves are used for livestock feed, and wood is valued as a building material.» But in a number of Indo-European dialects that have lost the old word (like Indo-Iranian languages), the name of the mulberry tree is transferred to blackberries. So in Greece (where both mulberry and blackberry grow) they have one name — moroy (already at Homer), and in Armenia mor, mori, moreni — blackberry (although the mulberry grows here too), Latin (morus — mulberry, morun — the fruit of the mulberry tree and blackberry).»

The strange thing about this situation is that if the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans was Asia Minor (the ancient homeland of the mulberry tree), then in the new territories the Indo-Europeans did not make sense to call this name anything else besides the well-known plant that grew on their ancestral home. And, nevertheless, despite the fact that mulberry is a tree of the «Near Asian ancestral home», that flour is made from its fruits in the Pamirs, Iran is generally the birthplace of a wild mulberry tree with black fruits (morus nigra), as well as Afghanistan that in India (as in China) is an ancient culture, «in Indo-Iranian dialects, the ancient Indo-European name has been preserved to denote a blackberry and only a blackberry, while the mulberry tree is characterized by completely different names that have nothing to do with the first.» T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov believe that the tree was given a new name in connection with the culture of breeding silkworms on it.»

The whole paradox is that the culture of breeding silkworms is associated with morus alba — a tree with white fruits, whose homeland is China, where it was first used to produce silkworm cocoons. On a tree with black fruits — morus nigra, whose homeland is Iran and Afghanistan, these worms do not live. So it is not at all clear why the tree that grew on the proposed ancestral home in Asia Minor and from the fruits of which they began to make flour in the new homeland, suddenly found a name here associated with silkworms that have nothing to do with it.

A different conclusion would be logical here. The name of the blackberry —

morus was primary, and subsequently, when promoting the Indo-Europeans in the territory of its distribution, the mulberry became so called because of the similarity of its berries to blackberries.

The distribution range of the blackberry is huge. Only in Russia 52 species of this berry are known: Nessa blackberry, or cumanica, growing in the forest and forest-steppe zone of the European part of Russia; cut blackberry — in the Baltic states, Belarus, Lipetsk region; bluish blackberry or burn, growing throughout the European part of our country, except the Far North, as well as in the Caucasus and

Central Asia, etc. It is possible that for blackberry this name — morus — was not at all monopolistic, because along with it, the rosaceous family includes such berries as polar meadow (princess, mamura or raspberry arctic) and cloudberry (moroska) (chamaemorus locke). Is the name of this beautiful northern berry, outwardly similar to a blackberry and different from it only in its honey color, connected with the ancient morus (this is how it is called «morus» in Sweden).

Blackberry, a subgenus of the Eubatus genus Rubus (raspberries, blackberries) is a family of Rosaceae. Shrubs with perennial rhizomes and biennial elevated shoots, usually covered with thorns. Fruits — prefabricated, juicy drupes, black or black-red, in many species with a bluish coating. Over 200 species are known that are common in North America and Eurasia; in the USSR — 42 species, mainly in the Caucasus, in the south of Ukraine and in Central Asia. These include: Caucasian blackberry (R. sausicus), bloody blackberry (R. sanguineus), long-fruited blackberry (R. dolichocarpus), gray blackberry (R. caesius). Fruits contain 4—8% sugars, 0.8—1.4% acids, vitamin C and carotene. Used in fresh and dried form, for processing.

Cloudberry, Moroshka (Rubus chamaemorus), a plant of the Rosaceae family of the same genus as raspberries, blackberries, bone and others. Herbaceous perennial 5—20 cm tall, with a long creeping rhizome and erect annual stems. The leaves are kidney-shaped, wrinkled, 5-lobed, dark green. The fruit is a multi-shoot of red, later orange drupes with a pleasant aroma. It grows mainly in the tundra and taiga zones of the Northern Hemisphere along moss swamps, marshy forests; in the USSR in the north of the European part, in Siberia and the Far East, it often forms large thickets. Fruits contain 3—6% sugar, citric and malic acids, tannins and pectin; eaten for making jam and drinks. Good honey plant.

Grapes (Vitis) (map No. 8), a genus of plants from the grape family. About 70 species are known, distributed mainly in the warm and temperate zones of the Northern Hemisphere. The root system is powerful. The trunk is a liana (in a forest community, a climbing plant). The fruit is a berry with small hard seeds and a well-developed pericarp. Among cultivated grape varieties, there are varieties with seedless berries. Berries have a different color and are collected in fruit fruit -clusters.

In winter, most varieties withstand frosts of -18° C. In the phase of bud blooming, spring frosts are harmful (2—3° C). The best temperature for development in spring is 15—20° C, in summer and autumn 20—25° C. When the temperature drops to 8—10° C, growth and development ceases. Temperatures above 40° C can cause burns to leaves, berries and young shoots. The crop requires 300 to 500 mm of rainfall, which falls evenly over the seasons of the year.

Light grapes are chosen for grapes: loamy, sandy, which contain a large amount of crushed stone, cartilage, stones.

Industrial culture is developed between 34—52° N. and 20—40° S in Europe, the northern border of its cultivation in open ground passes through Paris, Liege, Dusseldorf, Kamenetz-Podolsky, Saratov. In the USSR, viticulture is developed mainly in Moldova, in the south of Ukraine and the RSFSR, in the Caucasus, Central Asia.

The initial form from which the cultivated grape varieties originated was wild European grapes (V.vinifera, subsp.silvestris), which is common in the USSR in the valleys of the river Dnieper and Dniester, in the forests of Crimea, the North Caucasus, Transcaucasia, in the gorges of Kopetdag.

The authors of the «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans» write that the Indo-Iranian term lacks the Indo-European term for wine and grapes. But in Iran, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, wild grapes grow. It also grows in Asia Minor, and L. S. Berg noted that: «In Palestine, grapes now find the southern limit of their distribution. In biblical times, the Palestinian plateau was famous for its vineyards, but further Palestine in the south was not widespread.» A strange situation is once again emerging with Indo-Iranian languages. Grapes grow in the «Near-Asian ancestral homeland», in the new homeland — the Iranian Highlands, too, but there is no Indo-European term for wine and grapes.

T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov believe that: «it can be assumed that the place of wine as a cult and household drink in the Indo-Iranian tradition begins to take other intoxicating drinks made not from grapes, but from other plants that replaced grapes in new ecological conditions of the ancient Indo-Iranians.»

But what, these new environmental conditions, if in Asia and Iran, we repeat, grapes grow equally successfully, and even in the wild in Iran. Wild grapes are also growing in Tajikistan, another new homeland of the ancient Iranians. Why look for other plants for making wine as a cult and domestic drink, if the well-known grapes have always been at hand. It’s another matter if Indo-Iranians did not know grapes in their original Indo-European ancestral home, since it didn’t grow in their original habitats, and they prepared heady drinks using other plants, such as hops. But then, Asia Minor was not their oldest ancestral home.

And moreover, the initial formation of the Indo-Iranian peoples probably took place in territories much more northern not only in relation to the Near East and Asia Minor, but even to Ukraine, since here it is in Tripoli settlements (4 thousand BC) already cultivated a cultivated grape variety, although it had a small berry.

Researchers believe that as early as 4 thousand BC «Viticulture, for which the natural conditions of the Dniester-Prut interfluve were quite favorable, has become a new branch of agricultural production in Trypillian society.» Moreover, over the millennia there has been a directed selection and selection of cultivars, as evidenced by 3 thousand BC found in the settlement. Varvarovka VIII grain large table grapes.

Among the trees of the Indo-European ancestral home T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov also call ash, willow, aspen, poplar, alder, apple, cherry.

Ash (Fraxinus) (map No. 2), a genus of plants of the olive family. Trees, sometimes shrubs. Over 60 species in Eurasia, North America and North Africa, China, Japan, South and Central Europe and Asia Minor. There are 11 species in the USSR, in the European part, in the Caucasus, Crimea, the Carpathians, in Central Asia and in the Far East.